Simeon Solomon (1840-1905) stands as a fascinating, complex, and ultimately tragic figure within the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. Initially celebrated as a prodigious talent associated with the later phase of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and a key participant in the burgeoning Aesthetic Movement, Solomon's career was dramatically curtailed by personal scandal and societal prejudice. His work, notable for its exploration of Jewish themes, classical mythology, and increasingly overt homoeroticism, offers a unique window into the artistic and social currents of his time. Once largely obscured, Solomon's art and life have undergone significant re-evaluation, securing his place as an important artist whose legacy resonates particularly within Jewish art history and LGBTQIA+ art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Simeon Solomon was born into a prominent Orthodox Jewish family in Bishopsgate, London, in 1840. He was the eighth and youngest child of Michael Solomon, a successful Leghorn hat merchant and a notable figure in the London Jewish community, and Catherine Levy, herself an artist. Artistry ran strongly in the family; two of Simeon's older siblings, Abraham Solomon (1823-1862) and Rebecca Solomon (1832-1886), were already established painters by the time he began his training. This familial environment undoubtedly fostered his early artistic inclinations.

Around 1850, Simeon began receiving formal instruction, likely initially from his elder brother Abraham. His talent was evident early on, leading him to enroll at Carey's Art Academy in Bloomsbury in 1852. Francis Stephen Cary's academy was a well-regarded preparatory school for aspiring artists aiming for the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Solomon progressed quickly, and by 1857, he was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools, the foremost art institution in Britain at the time.

His debut at the Royal Academy's annual exhibition came swiftly in 1858. He continued to exhibit there regularly until 1872, showcasing works that quickly drew attention for their technical skill, imaginative compositions, and often unconventional subject matter. His early works frequently drew upon biblical narratives and scenes from Jewish life and ritual, reflecting his deep connection to his heritage.

Entry into the Pre-Raphaelite Circle

Solomon's entry into the influential circle surrounding the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood marked a pivotal moment in his development. While the original Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, had largely dissolved as a formal group by the late 1850s, its aesthetic principles continued to exert a powerful influence. Solomon became associated with the 'second generation' of artists inspired by Pre-Raphaelitism, largely through his introduction to Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Rossetti, along with Edward Burne-Jones and the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, became key figures in Solomon's artistic and social life. Rossetti, in particular, acted as a mentor, offering guidance and encouragement. Solomon quickly absorbed the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on detailed observation, jewel-like colour, complex symbolism, and a preference for subjects drawn from literature, religion, and medieval history. His draughtsmanship, already strong, gained a new intensity and decorative quality under this influence.

He formed a particularly close friendship with Edward Burne-Jones, who reportedly considered Solomon one of the greatest artistic talents of their generation. His association with Swinburne was also profound, both personally and artistically. Swinburne's poetry, often exploring themes of classical antiquity, sensual beauty, and forbidden desire, resonated deeply with Solomon's own developing sensibilities. Solomon would later provide illustrations for Swinburne's unpublished novel, Lesbia Brandon. This network provided crucial support and intellectual stimulation during his formative years.

Themes of Faith and Heritage

A distinctive aspect of Solomon's early work is his engagement with his Jewish identity. Unlike many of his Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries, whose religious subjects were predominantly Christian, Solomon frequently depicted scenes from the Hebrew Bible and Jewish rituals. This focus was relatively unusual in mainstream British art of the period and provided a unique perspective within the Pre-Raphaelite milieu.

His sister, Rebecca Solomon, who was also an accomplished artist exploring themes of social commentary and historical subjects, is believed to have influenced his choice of Jewish themes. Works like The Mother of Moses (1860), now in the Delaware Art Museum, and related studies such as Miriam Watching the Finding of Moses (c. 1859, Metropolitan Museum of Art) exemplify this period. These paintings are characterized by their emotional intensity, rich detail, and sensitive portrayal of biblical figures within carefully rendered settings.

Other works depicted contemporary or historical Jewish ceremonies, offering glimpses into a culture often misunderstood or exoticized by the wider Victorian public. These paintings were not merely illustrations but were imbued with a sense of personal connection and cultural pride. They demonstrated Solomon's ability to blend the detailed realism favoured by the Pre-Raphaelites with subjects drawn from his own lived experience and heritage, setting him apart from his peers.

Developing an Aesthetic Vision

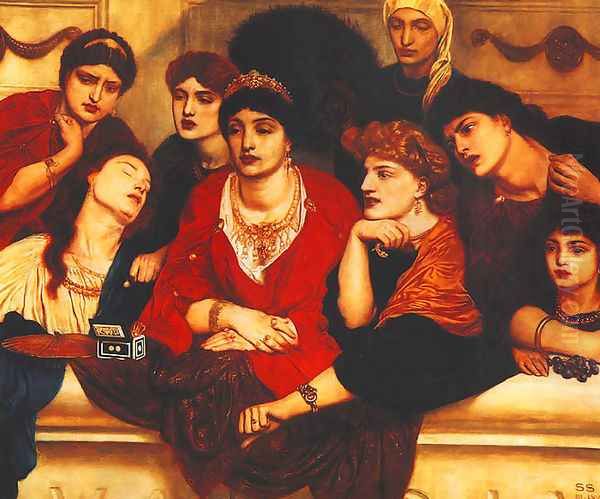

As the 1860s progressed, Solomon's style evolved, moving beyond strict Pre-Raphaelitism towards the emerging ideals of the Aesthetic Movement. While maintaining a high degree of technical finish and a love for decorative detail, his focus shifted towards mood, suggestion, and the pursuit of beauty as an end in itself – "art for art's sake," as championed by theorists like Walter Pater. Classical mythology and allegorical figures became increasingly prominent subjects.

His figures often took on a languid, androgynous quality, characterized by heavy-lidded eyes, full lips, and an air of melancholic introspection. The emphasis moved from narrative clarity towards evoking sensation and atmosphere. Works like The Magic Crystal (c. 1860s) showcase this transition, depicting a contemplative figure gazing into a crystal ball, the scene suffused with an aura of mystery and enchantment rather than telling a specific story. Colour palettes often became more muted and harmonious, emphasizing tonal subtleties.

This shift aligned Solomon with other artists associated with Aestheticism, such as James McNeill Whistler, Albert Moore, and Frederic Leighton, although Solomon's work retained a distinctive mystical and often more overtly sensual quality. His engagement with classical themes, particularly those from Greek mythology, provided a vehicle for exploring complex emotional states and, increasingly, themes of love and desire that deviated from conventional norms.

The Exploration of Homoeroticism

Perhaps the most defining, and ultimately most controversial, aspect of Solomon's art is its exploration of same-sex desire and gender ambiguity. From the mid-1860s onwards, homoerotic themes became increasingly central to his work, albeit often expressed through the coded language of mythology, allegory, or historical settings. This was a daring, even dangerous, path in Victorian Britain, where male homosexuality was legally proscribed and socially condemned.

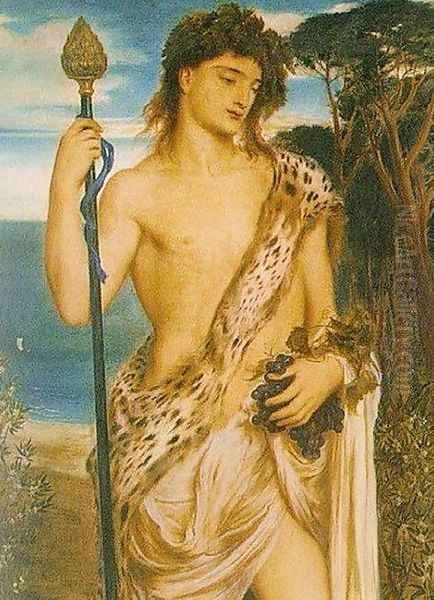

Works such as Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene (1864), depicting an intimate moment between the two female poets of ancient Greece, explored lesbian desire with unusual directness for the time. More frequently, Solomon focused on idealized male figures, often depicted in pairs or groups, charged with an ambiguous intimacy. Paintings like Pastoral Lovers (1869) and In the Summer Twilight (1869) present beautiful, androgynous youths in idyllic settings, their poses and gazes suggesting deep emotional and physical connection.

His drawings and watercolours, often more private than his exhibited oils, explored these themes with even greater intensity. Figures derived from classical mythology, such as Bacchus or Antinous, became recurring motifs, celebrated for their beauty and symbolic associations with ecstatic states and non-normative desire. Solomon's work in this vein often blurred traditional gender distinctions, presenting figures whose beauty transcended simple male/female binaries, reflecting the Aesthetic Movement's fascination with androgyny. This exploration was deeply intertwined with his personal life and his association with figures like Swinburne, whose own work pushed the boundaries of Victorian propriety.

The Scandal of 1873

Solomon's promising career trajectory came to an abrupt and devastating halt in 1873. On February 11th of that year, he was arrested in a public lavatory in Stratford Place, London, along with a man named George Roberts. They were charged with attempted sodomy. This public exposure of his homosexuality in a society deeply hostile to it proved catastrophic.

Solomon pleaded guilty and was initially sentenced to eighteen months of hard labour. However, through the intervention of influential relatives or friends (possibly his cousin, Mrs. Myer Salaman), the sentence was reduced, likely to police supervision, conditional on him avoiding further offenses. Despite escaping a lengthy prison term, the damage was done. The scandal became public knowledge, leading to immediate social and professional ostracism.

This event occurred more than two decades before the infamous trials of Oscar Wilde, but the societal condemnation was similarly severe. Solomon, once a celebrated figure in London's artistic circles, found himself shunned. Commissions dried up, galleries became hesitant to exhibit his work, and many former friends and patrons distanced themselves. The scandal effectively ended his public career as a major exhibiting artist in Britain.

Career in Decline

The aftermath of the 1873 scandal cast a long shadow over the remainder of Solomon's life and career. Although he continued to produce art, his output significantly diminished, and his circumstances became increasingly precarious. A further arrest in Paris in 1874, again on charges related to homosexual activity, resulted in a brief imprisonment of one month, further damaging his reputation.

Returning to London, Solomon struggled to regain his footing. The social exclusion was profound. Even former close associates like Swinburne reportedly severed ties, reflecting the intense social stigma attached to his conviction. He became increasingly reliant on the support of a few loyal friends and family members, but his financial situation deteriorated steadily.

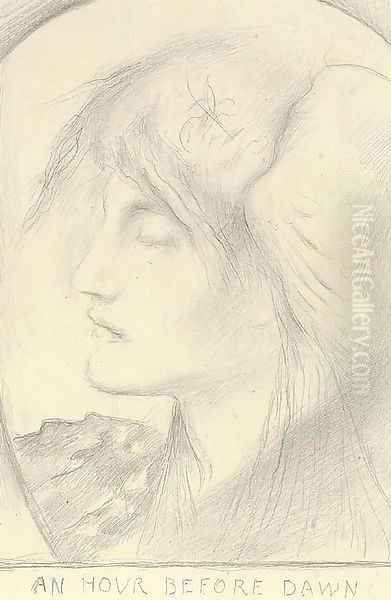

During this period, Solomon developed a serious problem with alcoholism, which further hampered his ability to work consistently and manage his affairs. He was known to sell drawings and sketches for small sums, often in pubs, simply to survive. While he continued to create works of haunting beauty, often focusing on single, melancholic heads or allegorical figures rendered in watercolour or chalk, these were typically smaller in scale and rarely exhibited formally. His descent into poverty and addiction marked a tragic decline from his earlier prominence.

Later Years and Final Works

By 1884, Solomon's circumstances had become so dire that he was admitted to the St Giles's Workhouse in Holborn, London. The workhouse system provided basic shelter and sustenance for the destitute, a stark indication of how far his fortunes had fallen. He would spend much of the last two decades of his life in and out of this institution.

Despite these hardships, he did not entirely cease artistic activity, though painting seems to have stopped around this time or become very sporadic. His interest in religious and mystical themes persisted, perhaps even intensified during his later years. There is evidence suggesting an attraction to Roman Catholicism, possibly finding solace in its rituals and symbolism, although it is unlikely he ever formally converted. Works like Mystery of Faith (c. 1870s), depicting a priest elevating the host, reflect this fascination with religious ceremony, interpreted by some modern scholars through the lens of his queer identity as potentially encoding homoerotic symbolism within the sacred ritual.

His health, undermined by years of alcoholism and poverty, eventually failed. Simeon Solomon died on August 14, 1905, in the St Giles's Workhouse infirmary. The cause of death was recorded as bronchitis and complications arising from alcoholism. He was 64 years old. He was buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Willesden, North London, a final return to the community of his birth.

Artistic Legacy and Rediscovery

For much of the twentieth century, Simeon Solomon remained a marginal figure in art history, his significant early achievements overshadowed by the scandal that derailed his career. His name was often mentioned only in passing in studies of the Pre-Raphaelites or the Aesthetic Movement, his contributions frequently downplayed or ignored.

However, beginning in the latter half of the century, a gradual process of rediscovery and critical re-evaluation began. Scholars started to look beyond the sensational aspects of his biography to appreciate the quality and originality of his art. Exhibitions dedicated to his work, such as the one held at the Geffrye Museum in London in 1966 and later, more comprehensive shows like "Love Revealed: Simeon Solomon and the Pre-Raphaelites" at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery in 2005-2006, brought his art back into public view.

Today, Solomon is recognized for his significant contributions to several areas. He is acknowledged as a key figure in the later development of Pre-Raphaelitism and an important exponent of Aestheticism. His exploration of Jewish themes provides valuable insight into Anglo-Jewish identity and artistic expression in the Victorian era. Crucially, he is now celebrated as a pioneering figure in the history of LGBTQIA+ art. His courageous, albeit often coded, exploration of same-sex desire and gender fluidity in a repressive era marks him as a significant precursor to later queer artists. His work influenced contemporaries and later figures associated with the Decadent movement, such as Aubrey Beardsley. His life and art continue to be subjects of academic study, particularly within gender studies and queer theory, offering rich material for understanding the complex interplay of identity, creativity, and societal constraint in the nineteenth century.

Solomon in Collections

Despite the vicissitudes of his career, a significant body of Simeon Solomon's work survives and is held in major public collections, primarily in the UK and the United States. Key institutions include:

Tate Britain, London: Holds several works, including drawings and paintings reflecting different phases of his career. (Note: The provided text mentioned Tate Modern, but Tate Britain is the primary repository for historical British art of this period).

Victoria and Albert Museum, London: Possesses a strong collection of his drawings and watercolours, including studies related to his biblical and classical subjects like Miriam Watching the Finding of Moses.

British Museum, London: Holds drawings and prints.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford: Has holdings of his work.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge: Contains examples of his art.

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery: Holds works and hosted a major retrospective.

Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, USA: Home to the important oil painting The Mother of Moses.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Collects his work, including drawings related to the Moses theme.

Jewish Museum London: Holds works relevant to his Jewish heritage, such as Moon and Sleep (1890).

Numerous works also remain in private collections, occasionally appearing at auction. The presence of his art in these prestigious institutions underscores his historical importance and the renewed appreciation for his unique artistic vision.

Conclusion

Simeon Solomon's life presents a poignant narrative of exceptional talent thwarted by personal struggles and the rigid intolerance of Victorian society. As an artist, he navigated the currents of Pre-Raphaelitism and Aestheticism, creating a body of work distinguished by its technical finesse, imaginative depth, and willingness to explore challenging themes. His engagement with his Jewish heritage offered a unique voice within British art, while his exploration of homoeroticism and androgyny marked him as a courageous pioneer.

Though his public career was tragically cut short by scandal, leading to decades of obscurity and hardship, Solomon's art endured. Its rediscovery in recent decades has rightfully restored him to a significant place in nineteenth-century art history. He is remembered not only for the haunting beauty of his paintings and drawings but also as a vital figure whose work continues to speak powerfully about faith, identity, desire, and the enduring human quest for beauty in the face of adversity. His legacy is particularly potent within LGBTQIA+ art history, where he stands as an early and important ancestor.