Sir Joseph Noel Paton stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art. A proud Scotsman, his multifaceted career encompassed painting, illustration, sculpture, poetry, and antiquarianism. Renowned particularly for his intricate and imaginative depictions of fairy lore, mythology, religious allegories, and historical scenes, Paton carved a unique niche for himself, bridging the romanticism of the early century with the detailed realism championed by movements like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with whom he shared close ties. His work, deeply imbued with a sense of narrative and moral purpose, captivated the Victorian imagination and earned him considerable acclaim, including a knighthood and the prestigious appointment as Queen's Limner for Scotland.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Dunfermline

Joseph Noel Paton was born on December 13, 1821, in Wooer's Alley, Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. His father, Joseph Neil Paton, was a prosperous damask designer and manufacturer, a profession that undoubtedly exposed young Joseph to the principles of design and intricate pattern-making from an early age. His mother, Catherine McDiarmid, also played a role in nurturing his creative sensibilities. The industrial environment of Dunfermline, a center for linen and damask weaving, provided a backdrop of skilled craftsmanship that likely influenced his later meticulous attention to detail.

Paton's formal education began at Dunfermline School, followed by studies at the Dunfermline Art Academy. His artistic talents were evident early on, and he initially followed in his father's footsteps, working for three years as the head of the design department at a cotton print works in Paisley. This practical experience in applied arts honed his skills in composition and decorative detail, which would become hallmarks of his later easel paintings. However, his ambitions lay in the realm of fine art, prompting his move to London to further his artistic education.

London, the Royal Academy, and Pre-Raphaelite Affinities

In 1842, Paton enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. During his time there, he studied under the tutelage of George Jones, a painter known for his battle scenes and historical subjects. It was in London that Paton formed a pivotal and lifelong friendship with John Everett Millais, one of the founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). Millais, along with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, sought to revolutionize British art by rejecting the formulaic classicism of the Academy, advocating instead for a return to the detailed realism, vibrant color, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian art.

While Paton was deeply sympathetic to the ideals of the PRB and shared their commitment to truth to nature, meticulous detail, and serious subject matter, he never formally became a member of the Brotherhood. His decision to return to Scotland in 1844, partly due to family reasons and a desire to establish his career in his homeland, precluded his official inclusion. Nevertheless, his artistic style, particularly in his early to mid-career, shows strong Pre-Raphaelite influences in its precision, bright palette, and emphasis on narrative clarity. He remained a close associate of Millais, and their mutual respect and artistic dialogue were significant for both.

The Rise of a Master of Fairy Painting

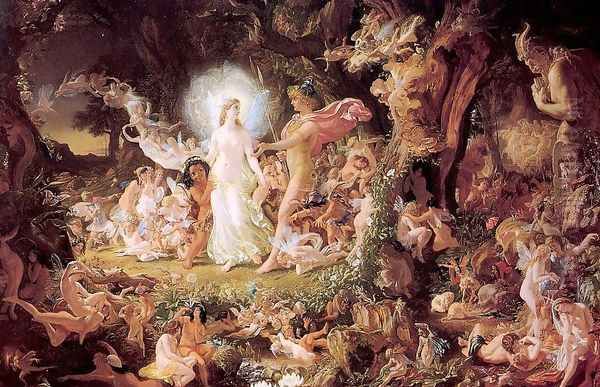

Paton first gained widespread public recognition with his paintings based on literary and fantastical themes. His two most celebrated early works, The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania (1849, exhibited Royal Scottish Academy 1850) and its companion piece, The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania (1847, exhibited Royal Academy 1847), catapulted him to fame. These large, incredibly detailed canvases, inspired by Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, are masterpieces of Victorian fairy painting.

The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania depicts the moment of dispute between the fairy king and queen over the Indian changeling boy. The canvas teems with an astonishing multitude of fairy figures, each meticulously rendered with individual character and engaged in various activities, set within a lush, minutely observed woodland scene. The painting won a prize in the Westminster Hall competition of 1847, which aimed to select artists for decorating the new Houses of Parliament, although Paton's work was ultimately not chosen for a fresco. Its success, however, was undeniable, praised for its imaginative power and technical brilliance. John Ruskin, the influential art critic and champion of the Pre-Raphaelites, admired Paton's skill, though he sometimes critiqued what he perceived as an overabundance of detail at the expense of broader effect.

The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania followed, showcasing a similar density of figures and botanical accuracy. These works tapped into a burgeoning Victorian fascination with the supernatural, folklore, and the unseen world of fairies. Other artists, such as Richard Dadd, with his hauntingly intense fairy paintings like The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke, and later Arthur Hughes, explored similar themes, but Paton's grand scale and narrative ambition set his contributions apart. His painting The Fairy Raid: Carry Off a Changeling – Midsummer Eve (1867) is another significant work in this genre, demonstrating his sustained engagement with fairy lore.

Expanding Horizons: Religious, Historical, and Allegorical Works

While fairy paintings secured his early reputation, Paton's artistic ambitions extended to a wider range of subjects, including religious, historical, and allegorical themes. He saw himself as a "Christian painter," and many of his works carry strong moral or spiritual messages. The Spirit of Religion (1845), also known as The Pursuit of Pleasure, was another prize-winning entry in the Westminster Hall competitions, showcasing his ability to handle complex allegorical subjects.

His religious paintings often aimed to inspire piety and contemplation. Works like Lux in Tenebris (1879), depicting Christ as the light in darkness, and Vade Satana! (1890s), showing Christ's temptation, were popular as engravings, reaching a wide audience. These later religious works often adopted a more sombre palette and a less crowded composition compared to his earlier fairy paintings, focusing on the central spiritual drama. He also painted historical scenes, often drawn from Scottish history and legend, reflecting his deep patriotism. An early example includes The Harvesters (1844), which, while perhaps more genre than strictly historical, shows his interest in depicting scenes of Scottish life. The Gate of Death (1858) is another notable work, likely allegorical in nature, reflecting Victorian preoccupations with mortality and the afterlife.

Paton's commitment to narrative and didactic art aligned him with other prominent Victorian painters who tackled grand themes, such as Daniel Maclise, known for his large-scale historical frescoes in the Palace of Westminster, and William Dyce, a fellow Scot who also contributed to the Parliament decorations and painted significant religious and historical subjects.

A Prolific Illustrator

Beyond his easel paintings, Paton was a highly accomplished and sought-after illustrator. His meticulous drawing style and imaginative flair translated perfectly to the medium of book illustration, which was flourishing in the Victorian era. He contributed illustrations to Samuel Carter Hall's The Book of British Ballads (1842-44), a project that also involved other artists. His work here demonstrated his early affinity for romantic and folkloric themes.

He created memorable illustrations for editions of Shakespeare's The Tempest and A Midsummer Night's Dream, naturally extending his visual interpretations of these plays beyond his famous paintings. His illustrations for Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (published by the Art Union of London, 1863) are particularly noteworthy, capturing the poem's eerie and supernatural atmosphere with powerful imagery. He also provided designs for Shelley's Prometheus Unbound and other literary works. This aspect of his career places him alongside other artist-illustrators of the period, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and later figures like Arthur Rackham, who would continue the tradition of fantastical illustration.

Poetry, Sculpture, and Antiquarian Pursuits

Paton's creative energies were not confined to the visual arts. He was also a published poet, producing two volumes: Poems by a Painter (1861) and Spindrift (1867). His poetry often explored themes similar to those in his paintings – nature, mythology, and spiritual reflection. While his poetic output did not achieve the same level of fame as his artwork, it underscores the breadth of his intellectual and artistic interests.

He also ventured into sculpture, though less frequently. One notable commission was for a monument to Lord Stuart de Rothesay, though this project was ultimately withdrawn due to public objections or disagreements over the design. His interest in the three-dimensional form, however, is evident in the sculptural quality of the figures in his paintings.

Furthermore, Paton was an avid collector of arms and armour, and other antiquities. His father had also been a collector, and Paton inherited and significantly expanded this collection, which adorned his Edinburgh home. This passion for historical artefacts informed the accuracy of costume and accoutrements in his historical and mythological paintings. After his death, this extensive collection was dispersed, a loss to the cohesive understanding of his antiquarian interests.

Public Recognition and Later Career

Paton's contributions to art and culture were widely recognized during his lifetime. He was elected an associate of the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in 1847 and became a full academician in 1850. His works were regularly exhibited at the RSA and the Royal Academy in London.

In 1866, he received a knighthood from Queen Victoria, a significant honour that acknowledged his status as one of the leading artists of his day. In 1870, he was appointed Queen's Limner for Scotland, a prestigious royal office that further cemented his position within the Scottish artistic establishment. Queen Victoria herself was an admirer of his work, and he enjoyed royal patronage.

His later career saw a continued production of religious and allegorical works. While the vogue for fairy painting had somewhat diminished by the late Victorian period, Paton remained committed to art with a high moral or spiritual purpose. He continued to live and work in Edinburgh, a respected elder statesman of Scottish art.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Paton's long friendship with Sir John Everett Millais was a defining relationship in his artistic life. Despite their different paths – Millais becoming a hugely successful and wealthy society painter and President of the Royal Academy, while Paton remained more focused on his specific thematic concerns in Scotland – their mutual respect endured.

He was also acquainted with John Ruskin, whose writings on art, particularly his championing of the Pre-Raphaelites and his emphasis on "truth to nature," resonated with Paton's own artistic principles. Ruskin's lectures in Edinburgh would have been known to Paton, and Ruskin, in turn, commented on Paton's work, sometimes with admiration for its skill and sometimes with reservations about its imaginative excesses.

As a prominent member of the Royal Scottish Academy, Paton would have interacted with many leading Scottish artists of his time, such as Thomas Faed, known for his sentimental genre scenes of Scottish rural life, and William Fettes Douglas, who also painted historical and literary subjects and later became President of the RSA. His early contemporary, David Scott, another Scottish historical painter with a penchant for the sublime and visionary, offers an interesting point of comparison in terms of ambition and thematic concerns, though Scott's career was tragically short. Paton's work can also be seen in the broader context of Victorian narrative painters like William Powell Frith, who captured contemporary life with similar attention to detail, or history painters like Edward Matthew Ward.

Personal Life and Character

Paton married Margaret Gourlay Ferrier in 1858, and they had a large family. His home at 33 George Square in Edinburgh became a hub of artistic and intellectual activity, filled with his collections. Anecdotes suggest a man of strong principles and deep religious conviction. One story, perhaps apocryphal but illustrative of his perceived character, tells of him calmly facing down armed intruders at his home through prayer and reasoned discourse, successfully defusing a dangerous situation. This speaks to a man of courage and steadfast faith, qualities often reflected in the moral certainty of his artistic themes.

His dedication to his Scottish roots was unwavering. Despite his early success in London and the potential for a more prominent career there, he chose to base himself in Scotland, contributing significantly to the cultural life of Edinburgh and the nation.

Legacy and Critical Re-evaluation

Sir Joseph Noel Paton passed away in Edinburgh on December 26, 1901, at the age of 80. By the time of his death, artistic tastes had begun to shift. The rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and various modern art movements led to a decline in the appreciation of Victorian narrative and highly finished academic painting. For much of the 20th century, Paton, like many of his contemporaries, was relatively neglected by art historians and the public, seen as representative of an outmoded artistic tradition.

However, the later 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a significant re-evaluation of Victorian art. Scholars and curators have increasingly recognized the richness, complexity, and technical brilliance of artists from this period. Paton's work, particularly his fairy paintings, has enjoyed a resurgence in popularity, appreciated for its imaginative power, intricate detail, and its insight into the Victorian psyche. His paintings are now prominent features in major collections, including the National Galleries of Scotland, the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow, and the Tate Britain.

His influence can be seen not only in the continuation of fantasy art but also in the broader appreciation for narrative and detailed craftsmanship. Artists like John William Waterhouse, though of a slightly later generation and often associated with a more classical Pre-Raphaelitism, shared Paton's interest in mythological and literary themes rendered with rich detail and romantic sensibility. The enduring appeal of fantasy illustration, from Arthur Rackham to contemporary artists, owes a debt to pioneers like Paton who legitimized and popularized such subjects within the realm of fine art.

Conclusion

Sir Joseph Noel Paton was an artist of remarkable talent, versatility, and vision. His contributions to Victorian art, particularly in the realm of fairy painting, religious allegory, and literary illustration, were substantial. He successfully navigated the artistic currents of his time, drawing inspiration from Romanticism, the Pre-Raphaelite ethos, and his own deep engagement with literature, folklore, and spirituality. A master of meticulous detail and complex composition, Paton created worlds that were both enchanting and imbued with profound meaning. While his reputation may have fluctuated with changing artistic fashions, his work endures as a testament to a unique imaginative gift and a significant chapter in the story of British art. His legacy is that of a dedicated craftsman, a vivid storyteller in paint, and a proud Scot who left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of his nation and beyond.