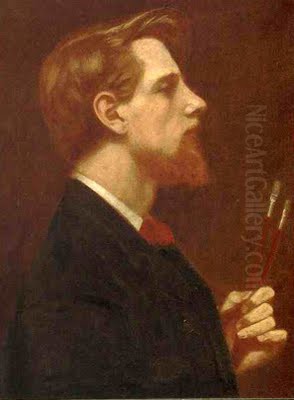

Thomas Cooper Gotch stands as a significant figure in British art during the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. An artist whose career traversed the earnest realism of the Newlyn School to embrace the ethereal realms of Symbolism, Gotch carved a unique niche for himself, particularly through his sensitive and often enigmatic portrayals of women and children. Born in Kettering, Northamptonshire, in 1854, and passing away in Newlyn, Cornwall, in 1931, his life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic transitions and cultural preoccupations of his time. He remains particularly noted for his exploration of female consciousness, innocence, and the spiritual dimensions of human experience, rendered in a style that blended meticulous technique with profound symbolic depth.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Thomas Cooper Gotch hailed from a reasonably prosperous middle-class background in Kettering, where his family was involved in the shoe trade and banking. This stable foundation allowed him to pursue his artistic inclinations. His formal art education began somewhat later than some of his contemporaries, initially studying at Heatherley's School of Fine Art in London in 1876 and later at the Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp in 1877. This period exposed him to the rigorous academic training prevalent on the Continent.

A pivotal move came in 1878 when he enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art in London under the tutelage of Alphonse Legros, a French-born artist who emphasized strong draughtsmanship. At the Slade, he met fellow artists who would become lifelong friends and colleagues, including Henry Scott Tuke and his future wife, Caroline Burland Yates, herself a talented painter. The Slade provided a more progressive environment than the Royal Academy Schools, fostering individuality alongside technical skill.

Following their time at the Slade, Gotch and Caroline Yates travelled to Paris in 1880, studying at the Académie Julian. This was a common path for ambitious British artists seeking exposure to the latest French artistic developments. In Paris, Gotch studied under Jean-Paul Laurens, a respected academic painter known for his historical scenes. This period further refined his technique and broadened his artistic horizons, exposing him to the currents of French realism and the burgeoning Symbolist ideas circulating in the city's artistic circles. He married Caroline in 1881, forming a partnership that was both personal and professional.

The Newlyn School Years

In the early 1880s, seeking authentic subjects and affordable living, many artists were drawn to rural communities. Following the lead of painters like Stanhope Forbes, who settled there in 1884, Thomas Cooper Gotch and his wife Caroline moved to the fishing village of Newlyn in Cornwall in 1887. Newlyn had become the centre of an influential artists' colony, known as the Newlyn School. The artists associated with this group were primarily interested in depicting the everyday lives of the local fishing community with honesty and realism, often working en plein air (outdoors) to capture natural light and atmosphere.

During his Newlyn period, Gotch adopted the prevailing style, focusing on social realist themes. His works from this time often depicted the hardships and simple dignity of the local people, rendered with careful observation and a somewhat sombre palette, characteristic of the school's early phase. He became a prominent member of the Newlyn group, exhibiting alongside figures such as Frank Bramley, Walter Langley, Norman Garstang, and Elizabeth Forbes (née Armstrong), Stanhope Forbes' wife and a significant artist in her own right.

Gotch played an active role in the colony's life, helping to establish the Newlyn Art Gallery and contributing to the organisation of exhibitions designed to showcase the group's work to a wider audience, particularly in London. His paintings from this era, while competent and well-received within the context of British realism, hinted at a decorative sensibility that would later come to the fore. However, his commitment to the strict social realism of the early Newlyn School would prove to be temporary.

A Shift Towards Symbolism and Italy

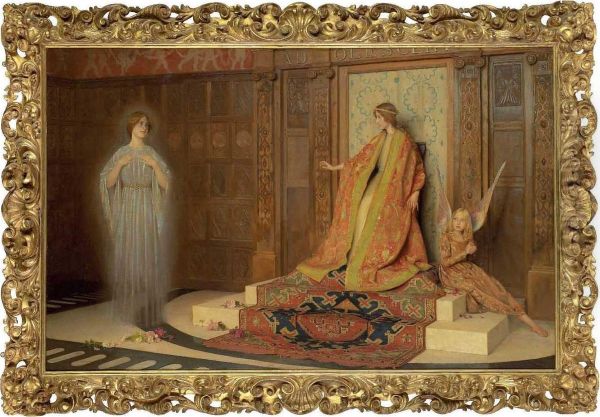

Around the early 1890s, a significant transformation occurred in Thomas Cooper Gotch's art. He began to move away from the social realism that defined the Newlyn School, embracing instead a more symbolic, decorative, and spiritually infused style. This shift was catalysed, in part, by a pivotal journey to Italy, particularly Florence, undertaken with his wife in 1891-1892. The experience of encountering the masterpieces of the early Italian Renaissance, especially the works of the Quattrocento painters like Botticelli and Fra Angelico, had a profound impact on him.

The clarity of line, the decorative richness, the flattened perspectives, and the spiritual intensity of early Renaissance art resonated deeply with Gotch. He was drawn to the way these artists combined realistic detail with allegorical meaning and a sense of the divine. This contrasted sharply with the more prosaic, earthbound subjects of his Newlyn period. His palette brightened, his compositions became more stylized and often incorporated elaborate costumes and decorative backgrounds, reminiscent of medieval and Renaissance aesthetics.

This stylistic evolution aligned Gotch more closely with the broader European Symbolist movement, which sought to express inner truths, emotions, and mystical ideas rather than simply depicting external reality. While he never fully abandoned figurative representation, his focus shifted towards allegory, myth, and the exploration of inner states, particularly those associated with childhood, adolescence, and female spirituality. This change marked a departure from his Newlyn colleagues, though he remained based in the area.

Exploring Womanhood and Childhood

The dominant themes in Gotch's mature work revolve around the depiction of women and children, often imbued with symbolic meaning. He became particularly renowned for his exploration of female consciousness and the transition from girlhood to womanhood. His paintings frequently present young women not merely as passive objects of beauty, but as figures embodying purity, spiritual awakening, or nascent inner strength. This focus coincided with contemporary debates about the "New Woman" and evolving societal roles, although Gotch's interpretations often leaned towards a more idealized and spiritualized vision of femininity.

One of his most celebrated works, The Dawn of Womanhood (c. 1900), exemplifies this theme. Exhibited to critical acclaim, the painting depicts a young woman on the cusp of adulthood, standing in a landscape that suggests both innocence and the threshold of experience. Critics praised its delicate handling and symbolic resonance, interpreting it as an allegory for the awakening of female potential and self-awareness. The figure's direct gaze and poised stance convey a sense of quiet dignity and burgeoning maturity.

Gotch also frequently painted children, often his own daughter Phyllis, capturing a sense of innocence, wonder, and sometimes a melancholic nostalgia for a perceived purity lost in adulthood. Works like The Child Enthroned (1894) present childhood with an almost religious reverence, elevating the subject beyond simple portraiture to a symbol of hope and untainted spirit. These depictions often feature rich textiles, flowers, and symbolic objects, enhancing the decorative quality and allegorical depth of the images. His interest extended to dream states and the liminal space between childhood and adolescence, exploring these themes with sensitivity and a touch of mysticism.

Key Works and Stylistic Hallmarks

Beyond The Dawn of Womanhood and The Child Enthroned, several other works define Gotch's mature style. My Crown and Sceptre (1892) is an early example of his shift, portraying a young girl in regal attire, suggesting the inherent dignity and potential of childhood. The use of rich fabrics and a formal pose signals his move towards a more decorative and symbolic approach.

Alleluia (1896), now in the Tate collection, is another significant work. It depicts a choir of young girls singing, clad in richly embroidered robes reminiscent of Renaissance vestments. The composition is formal and decorative, with a flattened perspective and a gold background that explicitly recalls early Italian religious painting. The work radiates a sense of spiritual devotion and collective harmony, celebrating youthful purity and divine praise through a highly stylized aesthetic.

The Lantern Parade (c. 1910, sources vary on exact date, possibly earlier or later iterations exist) showcases Gotch's interest in light, ritual, and community. Depicting children carrying lanterns in a procession, the painting captures a magical, almost mystical atmosphere. It combines his interest in childhood innocence with a fascination for folk customs and the evocative effects of light and shadow, themes also explored by contemporaries interested in folklore and tradition.

Gotch's stylistic hallmarks include meticulous attention to detail, particularly in rendering fabrics and textures, combined with a tendency towards flattened space and strong outlines, influenced by Renaissance frescoes and panel paintings. His colour palette became brighter and more jewel-like after his Italian trip. He often employed symbolic elements – flowers, specific colours, gestures, or objects – to convey deeper meanings related to innocence, spirituality, transition, or inner states. His work successfully blends Pre-Raphaelite intensity of detail with Symbolist suggestion and a unique, decorative sensibility.

Artistic Influences and Connections

Thomas Cooper Gotch's art reflects a confluence of influences. His early training provided a solid academic foundation in realism (Legros, Laurens). His time in Newlyn immersed him in British plein air naturalism (Forbes, Langley). The most decisive influence, however, was arguably the early Italian Renaissance (Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Ghirlandaio), which shaped his move towards decorative compositions and spiritual themes. He also absorbed aspects of the British Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, particularly their attention to detail, vibrant colour, and interest in medieval and literary subjects, though his work generally avoids their narrative complexity in favour of symbolic resonance. Figures like Edward Burne-Jones, with his dreamy medievalism and allegorical figures, represent a kindred spirit in British art.

Gotch was also aware of and responded to French Symbolism. While perhaps not directly influenced by figures like Gustave Moreau in the same way as some continental artists, the broader Symbolist ethos – the emphasis on suggestion over description, the exploration of dreams, myths, and inner states – clearly informed his mature work. His focus on idealized female figures as spiritual emblems aligns him with Symbolist tendencies seen across Europe.

Within the British context, Gotch maintained important relationships. His lifelong friendship with Henry Scott Tuke, another artist who balanced realism with more idealized depictions (particularly of male youth and the sea), was significant. While their subject matter differed, they shared a commitment to figurative art and mutual support. Gotch's later work also finds parallels with contemporaries like Robert Anning Bell and Frederick Cayley Robinson, who similarly explored themes of spirituality, allegory, and the "unseen" world, often employing decorative and sometimes archaic styles that stood apart from burgeoning Modernism. He can also be loosely compared to artists like John William Waterhouse, who also frequently depicted idealized female figures drawn from myth and literature, albeit often with a more overtly classical or narrative leaning.

Later Career, Reception, and Legacy

Thomas Cooper Gotch continued to paint and exhibit throughout the early 20th century, primarily at the Royal Academy in London, where he was a regular contributor despite his earlier stylistic independence. He also exhibited internationally, including at the Paris Salon. He maintained his home and studio in Newlyn, remaining connected to the Cornish art scene even as his style diverged from its origins. He also became involved in arts administration, serving as president of the Royal British Colonial Society of Artists (later the Royal Commonwealth Society) from 1913 to 1928.

However, the critical reception of Gotch's work became more muted as the 20th century progressed. The rise of Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and other avant-garde movements increasingly made his detailed, figurative, and symbolic style appear conservative or even anachronistic to modernist critics. Like many artists who adhered to late Pre-Raphaelite or Symbolist aesthetics, Gotch's reputation suffered a period of neglect during the mid-20th century, when formal innovation was highly prized. His emphasis on beauty, sentiment, and spiritual allegory seemed out of step with the harsher realities and artistic revolutions of the era.

In recent decades, however, there has been a renewed appreciation for Victorian and Edwardian art, including the various strands of Symbolism and Aestheticism. Art historians now recognize Gotch's unique contribution, particularly his sensitive and complex portrayals of female figures and children, which engage with contemporary ideas about psychology, spirituality, and gender. His ability to blend meticulous technique with evocative symbolism is increasingly admired. His work is seen as an important bridge between the realism of the Newlyn School and the more imaginative currents of British Symbolism.

Furthermore, Gotch's own writings and lectures reveal an interesting perspective on the role of the viewer. He emphasized that the meaning of a work of art was not solely dictated by the artist but required the active participation and interpretation of the audience. He believed art should evoke emotion and beauty, creating a connection between the artwork and the spectator's inner life. While these ideas may not have gained wide traction during his lifetime, they anticipate later developments in reception theory and underscore his thoughtful approach to his craft.

Conclusion: A Painter of Spirit and Transition

Thomas Cooper Gotch occupies a distinctive place in the landscape of British art. Beginning his career firmly rooted in the social realism of the Newlyn School, he underwent a profound transformation, embracing the symbolic potential and decorative beauty inspired by the Italian Renaissance and the wider Symbolist movement. His most memorable works are characterized by their sensitive exploration of childhood innocence and the complexities of female consciousness, often rendered with exquisite detail and a luminous, jewel-like palette.

While overshadowed for a time by the rise of Modernism, Gotch's art has found renewed appreciation for its technical skill, its emotional resonance, and its engagement with the spiritual and psychological currents of his era. He stands as a testament to an artist who forged his own path, moving from the depiction of external reality to the exploration of the inner world, leaving behind a legacy of hauntingly beautiful images that continue to speak of transition, spirituality, and the enduring mysteries of the human spirit. His work remains a significant contribution to British Symbolism and the rich artistic tapestry of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.