Sir Thomas Francis Dicksee, more commonly known as Frank Dicksee, stands as a prominent figure in the landscape of late Victorian art. A painter and illustrator renowned for his dramatic and highly finished depictions of literary, historical, and legendary scenes, as well as elegant portraits, Dicksee navigated the shifting tides of artistic taste at the turn of the 20th century, ultimately becoming a bastion of academic tradition as President of the Royal Academy. His work, characterized by its meticulous detail, rich colour, and sentimental appeal, offers a fascinating window into the aesthetic sensibilities of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Heritage

Born in London on November 27, 1853, Frank Dicksee was immersed in art from his earliest days. He hailed from a veritable dynasty of artists. His father, Thomas Francis Dicksee (1819–1895), was a notable painter in his own right, specializing in portraits and historical genre scenes, and a regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy. It was under his father's tutelage that young Frank received his initial artistic training, absorbing the fundamentals of draughtsmanship and composition within the family studio.

The artistic inclinations of the Dicksee family did not end there. Frank's brother, Herbert Thomas Dicksee (1862–1942), became a well-known painter and etcher, particularly celebrated for his sympathetic depictions of animals, especially dogs. His sister, Margaret Isabel Dicksee (1858–1903), also pursued a career as a painter, exhibiting genre scenes and historical subjects. This familial environment undoubtedly fostered a deep appreciation for art and provided a supportive framework for Frank's burgeoning talents. The shared passion for narrative and detailed execution was a hallmark of the Dicksee family's artistic output.

Formal Education and Early Success

Recognizing his son's prodigious talent, Thomas Francis Dicksee Sr. encouraged Frank to pursue formal art education. In 1870, Frank Dicksee enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Here, he proved to be an exceptional student, distinguishing himself early on. He won a silver medal for drawing from the antique in 1872 and, significantly, a gold medal in 1875 for his historical painting, Elijah confronting Ahab and Jezebel in Naboth's Vineyard. This award was a strong indicator of his future trajectory, highlighting his skill in composing complex, multi-figure historical narratives, a genre highly esteemed by the Academy.

During his time at the Royal Academy Schools, Dicksee would have been exposed to the teachings and works of established academicians. Figures like Lord Frederic Leighton, who would later become President of the Royal Academy, and Sir John Everett Millais, a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who had transitioned to a more academic style, were dominant forces. Their emphasis on technical skill, historical subjects, and polished finish would have resonated with Dicksee's own developing aesthetic. He also began working as an illustrator for magazines such as Cassell's Magazine, The Graphic, and The Cornhill Magazine during the 1870s, honing his narrative skills and gaining valuable professional experience.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Frank Dicksee's artistic style is firmly rooted in the Victorian academic tradition, with strong leanings towards late Pre-Raphaelitism and Romanticism. His paintings are characterized by their meticulous attention to detail, smooth and highly finished surfaces, rich and jewel-like colours, and a strong sense of drama or sentiment. He excelled in creating compositions that were both visually sumptuous and emotionally engaging.

His thematic concerns were diverse but often revolved around literary, historical, and mythological subjects. Shakespearean scenes were a recurring source of inspiration, allowing him to explore themes of love, tragedy, and chivalry. He was also drawn to medieval romance and Arthurian legends, subjects popularized by poets like Alfred, Lord Tennyson, whose works provided rich visual imagery for many Victorian artists. The idealized depiction of women, often portrayed as beautiful, ethereal, or tragically romantic figures, is a prominent feature of his oeuvre. This aligns with a broader Victorian fascination with romanticized femininity and chivalric ideals.

While sometimes compared to the Pre-Raphaelites for his detail and literary themes, Dicksee's work generally lacks the intense symbolism or the social critique found in the earlier works of artists like William Holman Hunt or Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Instead, his art aligns more closely with the later, more aesthetic and romantic phase of the movement, as seen in some works by Edward Burne-Jones, or with the classical and historical grandeur of contemporaries like Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Edward Poynter. Dicksee's focus was often on creating a visually beautiful and emotionally resonant image, rather than conveying complex allegorical messages.

Masterpieces and Defining Works

Several paintings stand out as defining examples of Frank Dicksee's artistic vision and technical prowess.

_Harmony_ (1877): Exhibited at the Royal Academy when Dicksee was just 24, this painting was a significant early success and was purchased under the terms of the Chantrey Bequest for the nation. It depicts a young woman playing an organ in a dimly lit, stained-glass windowed room, while a young man leans over her, listening intently. The mood is one of quiet intimacy and shared aesthetic experience, a theme popular in Victorian art. The rich colours, detailed rendering of textures, and sentimental atmosphere are characteristic of Dicksee's style. It drew comparisons with the work of artists like Leighton for its aesthetic sensibility.

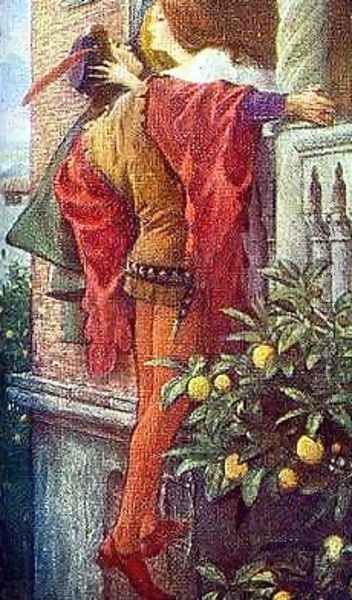

_Romeo and Juliet_ (c. 1884): This iconic portrayal of the famous balcony scene from Shakespeare's play is one of Dicksee's most beloved works. It captures the passion and tenderness of the young lovers with a lush, romantic sensibility. The rich colours, the detailed rendering of fabrics and foliage, and the expressive figures make it a quintessential example of Victorian romantic painting. The work demonstrates his skill in conveying intense emotion through gesture and facial expression.

_Chivalry_ (1885): Also known as The Symbol, this painting depicts a knight in shining armour rescuing a distressed damsel tied to a tree, while another, defeated knight lies on the ground. It embodies the Victorian idealization of medieval chivalry and heroism. The meticulous detail in the armour, the landscape, and the figures, combined with the dramatic narrative, made it a popular success. It reflects the era's fascination with romanticized historical themes, also explored by artists like John William Waterhouse.

_La Belle Dame sans Merci_ (c. 1901-1902): Inspired by John Keats's poem, this painting shows an enthralled knight captivated by a beautiful, enigmatic faery woman in a desolate landscape. Dicksee masterfully conveys the poem's themes of enchantment, obsession, and impending doom. The ethereal beauty of the woman and the knight's spellbound expression are rendered with exquisite detail and a haunting atmosphere. This work aligns with the Symbolist tendencies present in late Victorian art, where mood and suggestion were paramount.

_The Two Crowns_ (1900): This large and ambitious allegorical painting depicts a young king, clad in magnificent armour and riding a white charger, passing through a triumphal arch. He looks up to see a vision of Christ on the crucifix, also crowned, but with thorns. The painting contrasts earthly glory with spiritual sacrifice, a theme with deep resonance in the Victorian period. The meticulous detail, rich pageantry, and moral message are characteristic of grand academic painting.

_The Funeral of a Viking_ (1893): This dramatic and evocative painting depicts the Norse ritual of sending a deceased chieftain out to sea on a burning longship. The fiery glow of the ship against the dark, stormy sea and sky creates a powerful and sombre mood. It showcases Dicksee's ability to handle large-scale historical compositions with a strong narrative and emotional impact, reminiscent of the historical ambitions of painters like George Frederic Watts in his allegorical works.

Portraiture: A Distinguished Facet

Beyond his narrative paintings, Frank Dicksee was also a highly sought-after and accomplished portrait painter. He possessed a talent for capturing not only a likeness but also the character and social standing of his sitters. His portraits are typically elegant, refined, and often flattering, reflecting the tastes of his affluent clientele.

He painted numerous society figures, including many distinguished women, whom he depicted with grace and an eye for fashionable attire and opulent settings. Notable examples include portraits of Lady Hillingdon, Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt, and the Duchess of Buckingham and Chandos. His male portraits, while perhaps less overtly romanticized, still conveyed a sense of dignity and authority. His skill in rendering textures – silks, velvets, jewels – was as evident in his portraits as in his subject paintings. In this field, he was a contemporary of other successful portraitists like John Singer Sargent, though Dicksee's style remained more formally academic compared to Sargent's impressionistic bravura.

The Royal Academy and Later Career

Frank Dicksee's career was closely intertwined with the Royal Academy of Arts. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1881 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1891. His commitment to the Academy's ideals and his consistent success in its exhibitions solidified his reputation.

The pinnacle of his academic career came in 1924 when he was elected President of the Royal Academy (PRA), succeeding Sir Aston Webb. This was a significant honour, placing him at the helm of Britain's most prestigious art institution. As President, Dicksee was a staunch defender of traditional artistic values in an era increasingly dominated by Modernist movements like Post-Impressionism, Cubism, and Fauvism, which he and many of his academic colleagues viewed with skepticism or outright hostility. He was knighted in 1925 and further honoured as a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO) in 1927.

During his presidency, he championed the importance of draughtsmanship, technical skill, and representational art. While this stance made him a figure of conservatism in a rapidly changing art world, it also provided a sense of continuity and stability for the Academy. He oversaw important exhibitions, including the influential display of Italian art in 1930 and the landmark exhibition of Dutch art.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Frank Dicksee operated within a vibrant and diverse late Victorian and Edwardian art scene. He was a contemporary of many notable artists, some of whom shared his aesthetic sensibilities, while others pursued different paths.

Artists like Lord Frederic Leighton, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Edward Poynter were fellow proponents of the academic tradition, creating highly finished paintings often based on classical or historical themes. John William Waterhouse, while also academic, often imbued his works with a more mystical and Pre-Raphaelite sensibility, particularly in his depictions of mythological women, sharing some thematic ground with Dicksee.

The legacy of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood continued to exert an influence. While the original members like Millais had moved on stylistically, later artists like Edward Burne-Jones developed a distinctive aesthetic that blended Pre-Raphaelite intensity with Symbolist and Aesthetic Movement concerns, creating dreamlike and decorative works. Dicksee's romanticism and attention to detail show an affinity with this later Pre-Raphaelite spirit.

Other significant figures of the era included George Frederic Watts, known for his grand allegorical paintings, and Hubert von Herkomer, a versatile artist active in painting, printmaking, and even early filmmaking. Portraiture flourished with artists like Luke Fildes and Walter Ouless, alongside the aforementioned John Singer Sargent. The rise of the New English Art Club, with artists like Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert, represented a move towards Impressionist and Post-Impressionist ideas, offering an alternative to the Royal Academy's dominance. Dicksee's adherence to tradition placed him in contrast to these more avant-garde developments. His own family, including his father Thomas Francis Dicksee Sr., and siblings Herbert and Margaret, also contributed to the rich tapestry of Victorian art.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Public Perception

Frank Dicksee was generally a well-respected figure, and his career was not marked by major public controversies in the way some of his more radical contemporaries were. His art, while sometimes criticized by proponents of modernism for being overly sentimental or academic, was largely popular with the public and with traditionalist critics.

One "controversy," if it can be called that, was more a reflection of changing tastes. As President of the Royal Academy, Dicksee was a vocal opponent of modern art. In his presidential addresses, he often lamented the decline of traditional skills and the rise of what he considered to be undisciplined and incomprehensible art forms. This stance, while applauded by conservatives, positioned him as an old guard figure in the eyes of the burgeoning modernist movement. For instance, his views would have stood in stark contrast to those of critics like Roger Fry, who championed Post-Impressionism.

An interesting aspect of his public image was his own appearance. Dicksee was known for his handsome features and distinguished bearing, often described as looking like one of the chivalrous heroes from his own paintings. This perhaps added to his popular appeal and his embodiment of traditional Victorian values.

There are no widely circulated "sensational" anecdotes about Dicksee; he appears to have been a dedicated professional, deeply committed to his art and to the institution of the Royal Academy. His knighthood and other honours attest to the high regard in which he was held by the establishment.

Legacy and Reappraisal

Frank Dicksee passed away in London on October 17, 1928, still serving as President of the Royal Academy. By the time of his death, the art world had undergone profound transformations. The academic tradition he represented was increasingly seen as outdated by a new generation of artists and critics embracing modernism. Consequently, for much of the 20th century, Dicksee's work, along with that of many of his Victorian contemporaries, fell out of critical favour and was often dismissed as overly sentimental or illustrative.

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a significant reappraisal of Victorian art. Scholars and curators have begun to re-examine this period with fresh eyes, appreciating its technical skill, narrative complexity, and cultural significance. Artists like Dicksee are now recognized for their craftsmanship and their ability to capture the aspirations, anxieties, and romantic ideals of their age.

His paintings, particularly works like Romeo and Juliet, La Belle Dame sans Merci, and Harmony, remain popular and are frequently reproduced. They evoke a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era of romance and chivalry. While he may not be considered an innovator in the modernist sense, Frank Dicksee was a master of his chosen style and a significant figure in the history of British academic art. His dedication to beauty, narrative, and technical excellence ensured his enduring appeal to a segment of the public, even as critical tides shifted.

Conclusion

Sir Frank Dicksee was an artist who perfectly encapsulated the romantic and academic spirit of late Victorian and Edwardian England. From his early training within an artistic family to his ascent to the Presidency of the Royal Academy, his career was marked by consistent achievement and a dedication to the highest standards of craftsmanship. His paintings, whether depicting scenes from literature, history, or the elegant likenesses of his contemporaries, are characterized by their rich colour, meticulous detail, and profound emotional resonance. While the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century would eventually overshadow the academic tradition he championed, Dicksee's work endures as a testament to a particular vision of art – one that valued beauty, storytelling, and the power of the painted image to transport and inspire. His legacy is that of a skilled and sensitive artist who created some of the most iconic and beloved images of his time, a true luminary of his era.