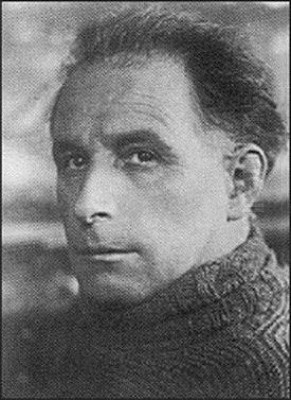

Gustave De Smet stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of early 20th-century Belgian art. Born in Ghent in 1877 and passing away in Deurle in 1943, he was a painter whose career traced a fascinating path through the evolving artistic currents of his time. He is primarily celebrated as one of the founders and leading proponents of Flemish Expressionism, a movement that sought to capture the soul of the Flemish region through a distinctively modern and emotionally charged visual language. Alongside contemporaries like Constant Permeke and Frits van den Bergh, De Smet forged an art form that was both deeply rooted in local identity and engaged with international avant-garde developments.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in Ghent

Gustave De Smet's entry into the world of art was perhaps influenced by his family environment. His father, Jules de Smet, worked as a set designer and photographer, immersing the young Gustave in a world where visual representation was paramount. Furthermore, his brother, Léon de Smet, also pursued a career as a painter, creating a familial atmosphere conducive to artistic pursuits. Both Gustave and Léon enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, a key institution in the region's artistic education.

At the Academy, Gustave studied under Jean Delvin, a respected painter and teacher. Interestingly, reports suggest that De Smet's performance during his academic years was not particularly outstanding. He did not initially distinguish himself as a star pupil. However, this period was crucial for forging connections that would shape his future. It was likely during or shortly after his time at the Academy that he began associating with artists who would later form the nucleus of the second Latem school, including the aforementioned Constant Permeke and Frits van den Bergh. These early interactions laid the groundwork for future collaborations and shared artistic explorations.

The Influence of Luminism and Sint-Martens-Latem

In his early career, before the dramatic shifts brought about by war and new artistic encounters, De Smet's work was significantly influenced by the prevailing styles of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Impressionism, with its focus on capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light, left its mark. More specifically, he was drawn to Luminism, a Belgian variant of Neo-Impressionism or Post-Impressionism that emphasized the play of light and shadow, often using bright colours and sometimes pointillist techniques. Figures like Emile Claus were central to Belgian Luminism, creating idyllic scenes bathed in sunlight.

De Smet became associated with the artists' colony at Sint-Martens-Latem, a village on the Leie river near Ghent that attracted painters seeking tranquility and a connection with rural life. While often linked with the "Second Latem School" (focused on Expressionism), his initial involvement connects him to the broader artistic ferment in the area. His works from this period often depicted landscapes, rural scenes, and intimate interiors, characterized by an attention to atmosphere and the nuances of light, reflecting the Luminist sensibility. This phase showed his grounding in established modern techniques before his more radical stylistic evolution.

Wartime Exile: A Catalyst for Expressionism

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 marked a profound turning point in Gustave De Smet's life and art. Like many Belgians facing the German invasion, De Smet sought refuge abroad. He fled with his family to the Netherlands, a neutral country during the conflict. They resided in various locations, including Amsterdam and possibly spending time in artists' communities like Blaricum or Laren, which hosted other Belgian refugees and Dutch modernists.

This period of exile proved artistically transformative. Separated from the familiar environment of Latem and exposed to a different artistic milieu, De Smet encountered international avant-garde ideas more directly. The Netherlands provided access to German Expressionism (perhaps through publications or exhibitions featuring artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Wassily Kandinsky) and the structural innovations of French Cubism (the influence of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque was spreading). A key figure he encountered was the French painter Henri Le Fauconnier, who was also in the Netherlands and worked in a style blending Cubism and Expressionism.

Interaction with Dutch modernists, such as Leo Gestel and Jan Sluyters, further broadened his horizons. Under these diverse influences, De Smet's style underwent a radical shift. He moved away from the light-filled, atmospheric concerns of Luminism towards a more structured, emotionally intense form of expression. Composition became simplified, forms grew more solid and sometimes distorted, and the emphasis shifted from objective representation to conveying subjective feeling and the underlying essence of the subject. This "Dutch period" laid the crucial groundwork for his mature Expressionist style.

Defining Flemish Expressionism

Upon his return to Belgium after the war, Gustave De Smet, alongside Constant Permeke and Frits van den Bergh, became central figures in consolidating Flemish Expressionism. This movement, while connected to broader European Expressionist trends, possessed distinct characteristics rooted in the local culture and landscape. It often favoured earthy colour palettes – deep browns, ochres, greens, and reds – reflecting the soil and rural life of Flanders.

Flemish Expressionism frequently focused on the lives of ordinary people: farmers, fishermen, villagers, and families. There was a tendency towards monumentalising figures, giving them a solid, sculptural quality that conveyed resilience and a deep connection to the earth. While German Expressionism often carried a strong sense of urban anxiety and psychological turmoil, the Flemish variant, particularly in the works of De Smet and Permeke, often expressed a more grounded, sometimes melancholic or stoic, but less overtly angst-ridden view of humanity and nature.

De Smet's contribution involved a unique synthesis. He combined the emotional intensity and subjective viewpoint of Expressionism with a strong sense of structure, often informed by Cubist principles. His compositions are carefully constructed, using simplified planes and strong outlines to define forms. His figures, while expressive, often possess a certain stillness and introspection, contributing to the characteristic mood of his work. He became a master at conveying deep emotion through restrained, powerful forms.

Key Themes in De Smet's Oeuvre

Gustave De Smet's body of work explores several recurring themes, providing insight into his artistic preoccupations and the world he observed.

Rural Life and the Flemish Landscape: Deeply connected to the Latem region and later Deurle, De Smet frequently depicted the rhythms of village life. His canvases feature farmers at work, quiet village streets, farmhouses nestled in the landscape, and the changing seasons. Works like The Shepherd (1928) exemplify this, portraying a harmonious, almost timeless vision of rural existence through simplified forms and a balanced composition. His landscapes often possess a solidity and structure that goes beyond mere representation, capturing the enduring spirit of the place. The painting Hunters in the Snow (1929) directly evokes the legacy of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, another artist deeply rooted in the Flemish landscape and peasant life, showcasing De Smet's awareness of this artistic lineage.

Intimate Human Relationships and Portraits: De Smet explored human figures and their interactions with sensitivity. The Lovers (1921) is a significant example, presenting a couple in a moment of quiet intimacy. The figures are somewhat stylized, almost "mechanical" as described in the source material, suggesting a modern sensibility applied to a timeless theme. The stillness and enclosed space create a contemplative atmosphere, perhaps hinting at the complexities of relationships and the future. He also painted numerous portraits, often characterized by their psychological depth and solid presence, capturing the inner life of his subjects through form and colour.

The World of Entertainment: Like many modern artists, De Smet was drawn to scenes of popular entertainment, particularly the circus and village fairs. The Clown (1920) captures the colourful yet potentially melancholic figure of the performer. These works allowed him to explore vibrant colour palettes and dynamic compositions, contrasting with the more subdued tones of his rural scenes. They reflect an interest in folk culture and the spectacle of public life, offering a different facet of human experience.

Still Life as Formal Exploration: In his later career, De Smet also turned his attention to still life. The source material mentions two still life paintings from 1938 and 1941 that included elements like playing cards. These works provided a platform for formal experimentation, allowing him to focus on composition, colour relationships, and the arrangement of objects in space. The inclusion of everyday items like playing cards grounds these formal exercises in the familiar world, perhaps hinting at themes of leisure, chance, or domesticity.

Analysis of Representative Works

Several key paintings encapsulate Gustave De Smet's artistic development and signature style.

Flower Bouquet (1917): Dating from his time in the Netherlands, this work likely represents a transitional phase. The "strong colour contrast" mentioned suggests a move away from the softer harmonies of Luminism towards the bolder palette associated with Expressionism and Fauvism. While still depicting a traditional subject, the handling of colour and perhaps form would indicate the new influences taking hold during his wartime exile.

The Clown (1920): Created shortly after his return to Belgium, this painting firmly establishes his Expressionist credentials. It likely employs bold colours, simplified forms, and perhaps a degree of distortion to convey the essence of the subject and the atmosphere of the circus, potentially blending vibrancy with an underlying sense of pathos often associated with clown figures in modern art.

The Lovers (1921): This iconic work showcases the mature Flemish Expressionist style. The figures are solid, almost sculptural, their forms simplified and contained within strong outlines. The composition is stable and enclosed, creating an intense, introspective mood. The palette is likely rich but possibly subdued, emphasizing the emotional weight of the scene. The "mechanical" quality noted might refer to the stylized, non-naturalistic rendering of the figures, typical of Expressionism's departure from realism to convey psychological states.

The Shepherd (1928): This painting represents a high point of De Smet's synthesis of Expressionism and Cubist structure. The landscape and figure are rendered through distinct, somewhat geometric planes of colour. The composition is highly ordered and balanced, creating a sense of profound peace and harmony between the human figure and the natural world. It embodies the calm, monumental quality often found in his depictions of rural life.

Hunters in the Snow (1929): This work demonstrates De Smet's engagement with art history, specifically the Flemish master Pieter Bruegel the Elder. While adopting Bruegel's theme and potentially compositional elements, De Smet translates it into his own modern language. The forms are simplified, the colours are characteristic of his palette, and the overall effect is one of stylized representation rather than detailed narrative, focusing on atmosphere and pattern.

Return to Deurle and Mature Synthesis

After the First World War, Gustave De Smet returned to Belgium and eventually settled permanently in Deurle, a village near Sint-Martens-Latem on the River Leie. This return marked the beginning of his most productive and influential period. His house in Deurle became a focal point, not just for his own work but also as a gathering place for fellow artists and writers, contributing to the continued cultural vibrancy of the Latem area.

His mature style, primarily developed during the 1920s and 1930s, represented a unique fusion. He retained the emotional core and subjective viewpoint of Expressionism but integrated lessons learned from Cubism regarding structure and form. His paintings from this era are characterized by their strong compositions, clearly defined shapes, often marked by thick outlines, and a sophisticated use of colour. While sometimes using muted, earthy tones associated with Flemish Expressionism, he could also employ richer, more vibrant colours when the subject demanded it.

His figures maintained their monumental, simplified quality, conveying a sense of permanence and inner gravity. Whether depicting peasants, portraits, or village scenes, there is a consistent feeling of thoughtful construction and emotional resonance. He avoided the extreme fragmentation of analytical Cubism and the raw, agitated brushwork of some German Expressionists, achieving instead a style that felt both modern and deeply rooted, balanced and powerful.

Networks, Collaborations, and Recognition

Gustave De Smet was not an isolated figure; he was deeply embedded in the artistic networks of his time. His closest collaborators were Constant Permeke and Frits van den Bergh, forming the triumvirate at the heart of Flemish Expressionism. They shared studios at times, exchanged ideas, and exhibited together, collectively shaping the movement's direction. His brother, Léon de Smet, remained a fellow painter, though his style often leaned more towards Impressionism and Intimism.

His association with Sint-Martens-Latem connected him with other significant artists of the region, including earlier figures associated with the first Latem school like the Symbolist sculptor George Minne or the landscape painter Valerius de Saedeleer, and fellow Expressionists like Albert Servaes, often considered one of the earliest proponents of the style in Flanders.

His time in the Netherlands forged links with Dutch modernists like Leo Gestel and potentially Jan Sluyters, as well as the influential French Cubist-Expressionist Henri Le Fauconnier. His interactions extended to the Brussels art scene, where he exhibited at prominent galleries like Galerie Georges Giroux (where he first showed his "Dutch period" works in 1920) and Galerie Le Centaure, run by the influential critic and promoter Paul-Gustave van Hecke.

De Smet was actively involved in several artists' groups aimed at promoting modern art, including 'Sélection' (which also had an associated influential journal/magazine co-founded by Van Hecke and André De Ridder, for which De Smet sometimes worked), 'Les Compagnons de l'Art', and later groups like 'L'Art Vivant'. These affiliations placed him at the centre of contemporary artistic discourse in Belgium. He also associated with artists like Edgard Tytgat and Jean Brusselmans, other key figures in Belgian modernism. His work gained recognition through participation in major exhibitions, such as shows at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels (1936) and the 'Kunst van Heden' (Art of Today) exhibition in Antwerp (1938). Precursors like James Ensor and contemporaries like the Fauvist-influenced Rik Wouters formed the broader context of Belgian modern art against which De Smet's unique contribution emerged.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Gustave De Smet continued to live and work in his house in Deurle. Sources suggest that health problems may have led to a reduction in his artistic output towards the end of his life. He passed away in Deurle in 1943, during the difficult years of the Second World War. His funeral was held in the modest village church.

A poignant testament to his deep friendship and artistic kinship with Constant Permeke is found on his tombstone, which reportedly bears Permeke's name alongside his own, a final acknowledgement of their shared journey in shaping Flemish Expressionism. His house in Deurle was later preserved and transformed into a museum dedicated to his life and work (Museum Gust De Smet), serving as a site of memory and appreciation for his contribution, although the operational status of small artist house museums can change over time.

Gustave De Smet's legacy lies in his crucial role in defining and developing Flemish Expressionism. He successfully synthesized international avant-garde ideas, particularly Expressionism and Cubism, with a sensibility deeply rooted in his Flemish environment. His work is celebrated for its structural coherence, emotional depth, and its powerful, often tranquil, depictions of rural life and human figures. Alongside Permeke and Van den Bergh, he created a distinct and enduring chapter in Belgian art history, influencing subsequent generations of artists in the region. His paintings remain highly regarded and are held in major museums in Belgium and internationally.

Conclusion

Gustave De Smet's artistic journey from the Luminist-influenced scenes of his early years to the powerful, structured forms of his mature Flemish Expressionist style charts a significant course through European modernism. Driven by personal experience, particularly his wartime exile, and engagement with international artistic currents, he forged a unique visual language. His collaboration with Constant Permeke and Frits van den Bergh was instrumental in establishing a movement that gave voice to a specific regional identity while participating in broader artistic dialogues. Through his memorable depictions of Flemish life, his insightful portraits, and his formally inventive still lifes, De Smet created a body of work characterized by emotional resonance, compositional strength, and a profound sense of place. He remains a key figure, essential for understanding the development of modern art in Belgium and the particular character of Flemish Expressionism.