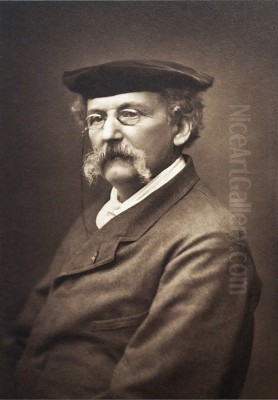

Théodule-Augustin Ribot stands as a significant, though sometimes overlooked, figure within the dynamic landscape of nineteenth-century French art. Born on August 8, 1823, in Saint-Nicolas-d'Attez and passing away on September 11, 1891, in Colombes, Ribot carved a distinct niche for himself within the Realist movement. He was a painter and etcher celebrated for his profound engagement with everyday life, his masterful use of chiaroscuro reminiscent of the Old Masters, and his ability to imbue humble subjects with quiet dignity and psychological depth. While contemporaries like Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet often command greater attention, Ribot's contribution to Realism, particularly his focus on intimate domestic scenes and his technical prowess, warrants closer examination.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Ribot's origins were modest, a factor that likely influenced his later artistic sensibilities. Born in the Eure region of Normandy, his father worked as a civil engineer. The family's circumstances necessitated practicality, and Ribot's initial training reflected this. He attended the École des Arts et Métiers in Châlons, a school focused more on industrial arts and trades than the fine arts curriculum of the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This practical grounding provided him with technical skills but set him apart from the traditional academic path followed by many aspiring painters of his generation.

Tragedy struck the family early when Ribot's father passed away. As a young man, Théodule found himself shouldering the responsibility of supporting his mother and sisters. This early encounter with hardship and familial duty seems to resonate through his later works, which often depict scenes of labor, domesticity, and quiet perseverance. His own life experiences provided a foundation for the empathy he would later show towards his working-class subjects.

Parisian Struggles and Artistic Beginnings

In 1845, seeking greater opportunities, Ribot made the pivotal move to Paris. The capital, however, did not offer immediate artistic success. He faced years of struggle, taking on various jobs to make ends meet. He worked as a decorator, gilding frames and painting shop signs, and even reportedly worked for a manufacturer of window blinds. These early jobs, while far from the glamorous life of a fine artist, kept him connected to the world of craft and visual production, honing his manual dexterity. During this period, he also married, adding further responsibilities to his already demanding life.

Despite the daily grind, Ribot's artistic ambitions remained undimmed. He dedicated his evenings and any spare moments to drawing and painting, often working late into the night by lamplight – a practice that perhaps contributed to his later fascination with dramatic light and shadow. Seeking formal instruction, he eventually entered the studio of Auguste Barthélemy Glaize, a painter known for his historical and allegorical subjects executed in a more conventional, academic style. While Glaize provided valuable training, Ribot's own artistic inclinations would soon lead him down a different path, away from academic convention and towards the burgeoning Realist movement.

The Emergence of a Realist Vision

The mid-nineteenth century in France was a period of artistic ferment. The staid Neoclassicism and idealized Romanticism that had dominated the official Salons were being challenged by a new generation of artists committed to depicting the world around them with unflinching honesty. Gustave Courbet famously championed this Realist cause, demanding that art engage with contemporary life and ordinary people. Ribot found himself drawn to this ethos.

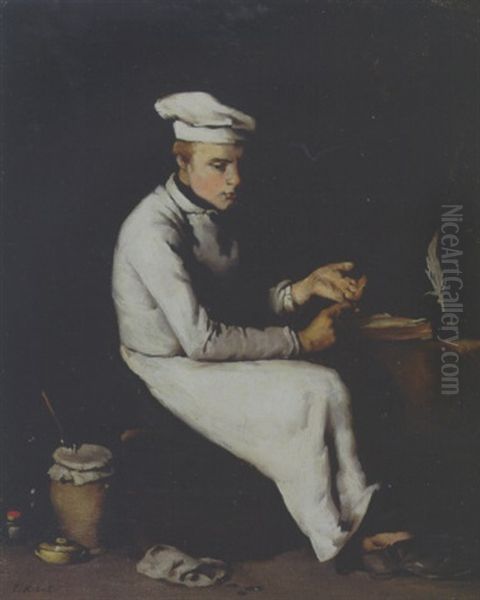

His breakthrough began in the late 1850s. He started producing paintings that focused on the subjects he knew best: scenes of everyday life, particularly those centered around the kitchen and the home. Cooks, scullions, apprentices, and family members became his protagonists. He painted still lifes composed of humble objects – kitchen utensils, oysters, fish, vegetables. This choice of subject matter aligned him with the Realist impulse to elevate the commonplace and reject the hierarchies of traditional genre painting.

A key figure in Ribot's early career was the painter François Bonvin. Bonvin, also known for his depictions of modest interiors and working-class life, shared Ribot's admiration for Dutch Golden Age painting and the works of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. Bonvin became a friend and supporter, recognizing Ribot's talent and helping him navigate the Parisian art world. It was through Bonvin's encouragement that Ribot began to exhibit his work more publicly.

Mastery of Chiaroscuro: Echoes of the Old Masters

Perhaps the most defining characteristic of Théodule Ribot's style is his dramatic use of chiaroscuro – the strong contrast between light and dark. His canvases are often enveloped in deep shadows, from which figures and objects emerge, illuminated by a focused, often unseen, light source. This technique imbues his work with a sense of intimacy, drama, and profound stillness.

Ribot's handling of light and shadow reveals his deep study and admiration of seventeenth-century Baroque masters. The influence of Spanish painters like Jusepe de Ribera, known for his stark realism and tenebrism, is particularly evident, especially in Ribot's religious works and some of his more dramatic figure studies. The psychological depth and textured surfaces achieved by Rembrandt van Rijn also resonate strongly in Ribot's paintings, particularly in his portraits and interior scenes. He adapted these historical techniques not merely as imitation, but to serve his own Realist ends, using light to model form, create atmosphere, and highlight the textures of everyday objects and the weathered faces of his subjects. His palette was typically somber, dominated by blacks, browns, ochres, and grays, punctuated by carefully placed highlights.

Themes in Ribot's Art: The Humble Kitchen

Ribot gained significant recognition for his kitchen scenes, a recurring theme throughout his career. These paintings depict the unglamorous, yet essential, world of cooks, scullions, and kitchen helpers. Works like The Cooks' Party (also known as Meeting of the Chefs) or The Accountant Cook (both circa 1860s) are prime examples. In these canvases, Ribot portrays his subjects with a seriousness and dignity typically reserved for historical or mythological figures.

He captures the textures of the kitchen environment – the gleam of copper pots, the rough surfaces of earthenware, the folds of aprons – with remarkable fidelity. The figures themselves are often shown engrossed in their tasks or in moments of quiet camaraderie. Ribot avoids sentimentality; instead, he presents these individuals with a directness and psychological presence. His use of chiaroscuro enhances the intimacy of these scenes, drawing the viewer into the enclosed space of the kitchen and focusing attention on the human element within it. These works can be seen as modern interpretations of Dutch genre scenes by artists like Adriaen Brouwer or Adriaen van Ostade, updated with a nineteenth-century Realist sensibility. Antoine Vollon, another contemporary French artist, also explored similar themes of kitchen still life and genre scenes, though often with a richer, more painterly technique.

Themes in Ribot's Art: Still Life's Quiet Drama

Alongside his genre scenes, Ribot was a dedicated painter of still life. His natures mortes often feature the bounty of the kitchen or the sea: oysters glistening in their shells, silvery fish arranged on platters, game birds, vegetables, and an array of pots, pans, and utensils. These compositions are typically simple and direct, focusing on the inherent beauty and texture of the objects themselves.

Influenced by the Spanish bodegón tradition, particularly the austere arrangements of Francisco de Zurbarán and the palpable realism of Diego Velázquez, Ribot imbued his still lifes with a sense of gravity and presence. He shared with the eighteenth-century master Chardin an appreciation for the humble object, but Ribot's approach is often starker, his lighting more dramatic. The intense focus achieved through chiaroscuro makes these everyday items seem monumental and intensely real. The tactile quality of his paint application further enhances this effect, inviting the viewer to almost feel the cool smoothness of an oyster shell or the rough skin of a lemon.

Themes in Ribot's Art: Religious Subjects Reimagined

While firmly rooted in Realism, Ribot did not shy away from traditional religious themes. However, he approached these subjects with the same commitment to tangible reality and dramatic lighting that characterized his secular work. His Saint Sebastian (1865), now housed in the Musée d'Orsay, is a powerful example. The saint's suffering is depicted with stark physicality, his body emerging dramatically from a dark background, reminiscent of Ribera's numerous treatments of the same subject.

Other religious works, such as The Good Samaritan or The Sermon of Christ, similarly translate biblical narratives into tangible, human dramas. Ribot avoids idealized beauty or overt displays of divine intervention, focusing instead on the human emotions and physical realities inherent in the stories. While some contemporary critics may have found his approach to religious art somewhat traditional or lacking in modern spiritual interpretation compared to the grand machines of academic painters, the intensity and sincerity of his vision lend these works a unique power. He grounded the sacred in the palpable reality he knew best.

Themes in Ribot's Art: Portraits and Intimate Figures

Portraiture and figure studies also formed an important part of Ribot's oeuvre. He often used his own family members as models, lending an air of intimacy and familiarity to these works. Paintings like Young Girl Combing Her Hair showcase his ability to capture quiet, private moments with sensitivity. His portraits are typically characterized by their directness and psychological insight.

Using his signature chiaroscuro, he would model the sitter's features, allowing light to reveal character while shadows suggested inner thoughts or mood. Unlike the society portraits of contemporaries like Carolus-Duran or Léon Bonnat, Ribot's portraits often focused on ordinary individuals, rendered with the same seriousness and attention to detail as his genre figures. His approach shares some affinity with the introspective portraits of his friend Henri Fantin-Latour, though Ribot's style remained generally darker and more heavily contrasted.

The Salon and Official Recognition

Despite his focus on humble subjects and his divergence from academic norms, Ribot sought and achieved recognition within the official art establishment of the Paris Salon. He made his Salon debut in 1861 with four kitchen scenes, which were well-received by critics and collectors, attracting favorable comparisons to the Spanish and Dutch masters he admired. This initial success marked a turning point in his career.

He continued to exhibit regularly at the Salon, winning medals in 1864 and 1865. This official validation helped solidify his reputation and brought his work to a wider audience. His success demonstrated that Realism, even in its more somber and intimate forms, could find acceptance within the system. In 1878, his artistic achievements were further acknowledged when he was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honour, a significant mark of distinction in France. This recognition placed him firmly among the respected painters of his time, even if he never achieved the widespread fame or notoriety of Courbet or Manet.

A Circle of Friends and Contemporaries

Ribot was part of a vibrant artistic community in Paris. His friendship with François Bonvin was crucial early on. He also formed lasting friendships with other artists who shared similar sensibilities or admired his work. Adolphe-Félix Cals, another painter of modest genre scenes, was a close associate. He was also connected with Henri Fantin-Latour and Alphonse Legros, both painters and printmakers who shared an interest in Realism and the techniques of the Old Masters.

James McNeill Whistler, the American expatriate artist, was another important connection. Whistler shared Ribot's admiration for Velázquez and Spanish painting, as well as an interest in etching. Ribot's circle demonstrates his position within a network of artists who were exploring alternatives to academicism, drawing inspiration from both past traditions and contemporary life. While associated with the broader Realist movement led by figures like Courbet and Jean-François Millet (known for his Barbizon school depictions of peasant life), Ribot maintained his own distinct artistic identity. He navigated a path that acknowledged the innovations of Realism while remaining deeply connected to the painterly traditions he revered, unlike the Impressionists such as Claude Monet or Edgar Degas who would soon revolutionize French painting in a different direction. His work also stands apart from the sharp social commentary found in the works of Honoré Daumier, focusing more on quiet observation than overt critique.

Ribot the Etcher

Beyond his work as a painter, Théodule Ribot was also a highly accomplished etcher. Printmaking offered another avenue to explore his characteristic themes and his fascination with light and shadow. He often created etched versions of his paintings, translating the dramatic contrasts of his canvases into the linear medium of print.

His etchings, like his paintings, show the strong influence of Rembrandt, who was himself a master etcher. Ribot skillfully used dense networks of lines and selective wiping of the plate to achieve rich, dark tones and dramatic highlights, mirroring the chiaroscuro effects of his oils. His prints often depict the same subjects: cooks, musicians, drinkers, and intimate domestic scenes. His involvement in etching connected him further with contemporaries like Legros and Whistler, who were central figures in the etching revival movement in France and England during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

In his later years, Ribot's artistic production seems to have slowed, possibly due to health issues. He continued to live and work, eventually settling in Colombes, a suburb of Paris, where he passed away in 1891.

Théodule Ribot's legacy is that of a dedicated and highly skilled painter who brought a unique sensitivity and technical mastery to the Realist movement. He excelled in depicting the dignity of humble labor and the quiet beauty of everyday objects. His masterful use of chiaroscuro, learned from the Spanish and Dutch masters, allowed him to create works of profound mood and psychological depth. While perhaps less revolutionary than some of his contemporaries, he played a vital role in broadening the scope of acceptable subject matter in French art and demonstrated how traditional techniques could be adapted to modern sensibilities.

Today, his works are held in major museum collections around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, and many others. While sometimes overshadowed by bigger names, exhibitions and scholarly attention continue to affirm his importance. He remains a key figure for understanding the nuances of French Realism, an artist whose somber palette revealed a deep appreciation for the substance and quiet drama of ordinary life. His focus on light, shadow, and psychological presence may also have subtly influenced later artists like Eugène Carrière, known for his own misty, atmospheric interior scenes. Ribot stands as a testament to the power of focused observation and technical skill in service of an intimate, humanistic vision.