Introduction: An Artist of Vision and Influence

Thomas Moran stands as a towering figure in the history of American art, renowned primarily for his dramatic and luminous paintings of the American West. An immigrant who embraced his adopted homeland, Moran became intrinsically linked with the landscapes he depicted, particularly the regions that would become iconic national parks like Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon. As a key member of the later generation of the Hudson River School and a central figure in the Rocky Mountain School, Moran's work transcended mere topographical representation. He infused his canvases with a Romantic sensibility, capturing the sublime power, vastness, and unique beauty of these territories, thereby shaping the visual identity of the American West for generations. His art not only brought these remote wonders to the attention of the American public and the world but also played a crucial role in the movement to preserve these natural treasures. Moran was a master technician, adept in oil, watercolor, and etching, and his prolific output continues to inspire awe and admiration.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

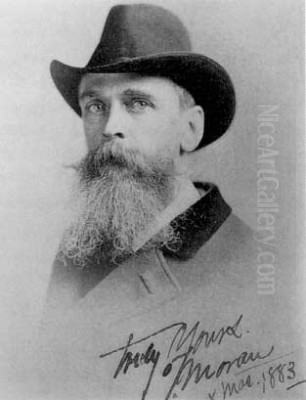

Thomas Moran was born in Bolton, Lancashire, England, on February 12, 1837. His family was involved in the textile trade, working with handlooms, a profession increasingly challenged by the Industrial Revolution. Seeking better opportunities, the Moran family emigrated to the United States in 1844 when Thomas was just seven years old. They initially settled in Kensington, a suburb of Philadelphia, later moving briefly to Maryland before returning permanently to Philadelphia. This city, a burgeoning cultural and artistic center, would provide the backdrop for Moran's early artistic development. He came from a family with notable artistic inclinations; several of his siblings also pursued artistic careers, most famously his older brother, Edward Moran, who became a distinguished marine painter.

Moran's formal artistic training began around the age of sixteen when he was apprenticed to the Philadelphia wood-engraving firm Scattergood & Telfer. Here, he honed his skills in draftsmanship and the detailed work required for illustration and printmaking. However, his passion lay more in painting. He spent much of his time sketching and developing his watercolor technique, often neglecting his engraving duties. After about two years, he left the apprenticeship to focus entirely on painting. He began working in the studio of his older brother, Edward Moran. Edward provided guidance and encouragement, and the brothers often sketched together. During this period, Thomas also came under the influence of the Philadelphia-based painter James Hamilton, known for his dramatic seascapes and imaginative, Turner-esque style. Hamilton's bold use of color and light likely made a significant impression on the young Moran.

The Lure of Europe and the Influence of Turner

Like many aspiring American artists of his time, Moran recognized the importance of studying European art firsthand. In 1861-1862, he made his first trip to England, a journey that would prove profoundly influential. His primary goal was to study the works of the great British landscape painter Joseph Mallord William Turner (J.M.W. Turner). Moran deeply admired Turner's mastery of light, color, and atmospheric effects, as well as his ability to convey the sublime power of nature. He spent considerable time copying Turner's paintings at the National Gallery in London, absorbing his techniques and artistic philosophy. Turner's influence is evident throughout Moran's subsequent career, particularly in his handling of light, his vibrant palette, and his often dramatic compositions.

During his time in London, Moran also sought out contemporary art and artists. He further developed his skills and broadened his artistic horizons. The encounter with Turner's work, combined with the rich artistic environment of Europe, solidified his commitment to landscape painting and equipped him with a more sophisticated understanding of color theory and composition. He also studied the works of Claude Lorrain, another master of idealized landscape and atmospheric light, whose structured compositions offered a counterpoint to Turner's more turbulent style. This European sojourn was crucial in shaping Moran's mature style, providing him with the tools to tackle the grand landscapes he would later encounter in America. He also met the influential art critic John Ruskin, a major proponent of Turner and advocate for truth to nature, whose ideas likely resonated with Moran.

Journey to the West: The Hayden Expedition and Yellowstone

The pivotal moment in Thomas Moran's career arrived in 1871. He was invited, partly through the influence of the financier Jay Cooke and Scribner's Monthly magazine (for which he provided illustrations), to join the United States Geological Survey of the Territories expedition to the Yellowstone region, led by geologist Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden. At this time, Yellowstone was largely unknown to the American public, a land of myth and rumor described by early explorers as a place of geysers, hot springs, and breathtaking canyons. Moran joined the survey as a guest artist, tasked with visually documenting the wonders encountered.

This expedition was transformative for Moran. Traveling alongside the survey team, which included the photographer William Henry Jackson, Moran sketched and painted furiously, capturing the unique geological formations, vibrant colors, and dramatic scenery of the Yellowstone basin. He was captivated by the otherworldly landscapes – the steaming geyser basins, the brilliantly colored hot springs like the Grand Prismatic Spring, the towering waterfalls, and especially the majestic Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River with its Lower and Upper Falls. His field sketches and watercolors, created under challenging conditions, served as the raw material for larger studio paintings upon his return.

The collaboration between Moran and Jackson proved particularly fruitful. Moran's evocative paintings and Jackson's stunning photographs provided compelling visual evidence of Yellowstone's wonders. Together, their work played an indispensable role in convincing the U.S. Congress to protect the area. Hayden included their images in his official report, using them to lobby lawmakers. The visual power of Moran's art helped sway opinions, leading directly to the establishment of Yellowstone as the world's first national park in March 1872. This cemented Moran's reputation not just as an artist, but as a figure whose work had tangible national significance.

Masterworks of the Western Landscape

Following the success of the Yellowstone expedition, Moran embarked on further journeys west, solidifying his reputation as the premier painter of America's grand natural spectacles. His experiences provided the inspiration for some of the most iconic images in American art history. Chief among these is The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (1872). This monumental canvas, measuring seven by twelve feet, synthesized Moran's field sketches and observations into a breathtaking panorama. It captures the immense scale, dramatic light, and vivid colors of the canyon, emphasizing the Lower Falls plunging into the chasm below. The painting was a sensation, and Congress, recognizing its artistic and national importance, purchased it for the substantial sum of ,000 to be displayed in the U.S. Capitol.

In 1873, Moran joined an expedition led by Major John Wesley Powell down the Colorado River, exploring the Grand Canyon in Arizona. This journey inspired another massive masterpiece, The Chasm of the Colorado (1873-1874). Similar in scale and ambition to his Yellowstone painting, this work conveys the staggering depth, intricate rock formations, and atmospheric haze of the Grand Canyon. Again, Moran employed dramatic light and shadow, a rich palette, and a panoramic perspective to communicate the sublime power and geological grandeur of the scene. This painting was also purchased by Congress for ,000, further cementing Moran's status as a national artist.

Moran continued to explore and paint the West throughout his career. Another significant work from this period is Mountain of the Holy Cross (1875), depicting a Colorado peak famous for a cross-shaped snowfield near its summit. This painting resonated deeply with a public interested in finding spiritual significance in the American landscape. He also frequently painted scenes along the Green River in Wyoming, such as The Cliffs of Green River (various versions), capturing the distinctive banded rock formations under dramatic skies. These major works, characterized by their scale, detail, Romantic sensibility, and brilliant color, defined Moran's contribution to American art and shaped the popular image of the West.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Philosophy

Thomas Moran's artistic style is deeply rooted in the Romantic tradition, emphasizing awe, grandeur, emotion, and the sublime power of nature over human scale. While associated with the Hudson River School, his work, particularly his Western scenes, often pushes beyond its typical pastoralism towards a more dramatic and spectacular vision, aligning him closely with the Rocky Mountain School alongside artists like Albert Bierstadt. His exposure to J.M.W. Turner was fundamental, evident in his fascination with light, atmosphere, and dynamic compositions. Moran masterfully used color not just descriptively but emotionally, employing vibrant hues – golden yellows, fiery oranges, deep blues, and rich reds – to heighten the drama and capture the unique atmospheric conditions of the West.

Moran was a versatile and technically skilled artist. While best known for his large-scale oil paintings, he was also an accomplished watercolorist. His watercolors often served as field studies but are also finished works in their own right, prized for their freshness and luminosity. He was also a master etcher and played a significant role in the American Etching Revival of the late 19th century. His etchings, often based on his paintings and sketches, allowed his images to reach a wider audience through publications like Scribner's Monthly and Harper's Weekly, and as standalone prints. His wife, Mary Nimmo Moran, whom he married in 1862, also became a celebrated etcher under his tutelage.

His process typically involved extensive travel and sketching directly from nature. He filled numerous sketchbooks with pencil drawings and watercolor studies, capturing details of geology, flora, and light effects. Back in his studio, he would synthesize these studies, often combining elements from different viewpoints or times of day, to create his large, carefully composed exhibition pieces. While striving for geological accuracy, Moran was not a strict topographer; he aimed to capture the spirit and essence of a place, often idealizing or dramatizing elements to enhance the overall effect and convey the profound emotional impact these landscapes had on him. He believed art should elevate and inspire, revealing the divine presence within the natural world.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

Thomas Moran's career unfolded within a vibrant artistic landscape, and his interactions with contemporaries and collaborators were significant. His closest artistic relationship was arguably with his brother, Edward Moran. They shared studio space early in their careers and maintained a lifelong connection, though their primary subjects differed – Edward focusing on marine scenes, Thomas on landscapes. Thomas's other artist brothers, Peter Moran (known for animal paintings and etchings) and John Moran (a photographer and painter), contributed to the artistic environment of the family. His marriage to Mary Nimmo Moran created another artistic partnership; she became a highly respected etcher, often interpreting Thomas's designs or creating her own landscape views.

The collaboration with photographer William Henry Jackson on the 1871 Hayden Survey was pivotal. Their complementary skills provided a powerful visual record of Yellowstone, demonstrating the synergy possible between painting and the newer medium of photography in documenting and promoting the West. Moran's participation in expeditions led by Ferdinand V. Hayden and John Wesley Powell placed him alongside scientists and explorers, highlighting the intersection of art and scientific discovery in the 19th century.

In the broader art world, Moran was a contemporary of the leading figures of the Hudson River School's second generation, such as Frederic Edwin Church and Sanford Robinson Gifford, who also undertook ambitious landscape projects. His most direct peer and sometimes rival in depicting the grand scale of the West was Albert Bierstadt. Both artists created enormous canvases celebrating Western scenery, though Bierstadt often favored the Rocky Mountains and Yosemite, employing a somewhat different, more Dusseldorf-influenced style. Other contemporaries painting the West included Thomas Hill and William Keith, associated with California landscapes. Moran also knew and interacted with many East Coast artists through organizations like the National Academy of Design (to which he was elected in 1884) and the Tile Club, a social group of prominent artists and writers including Winslow Homer and Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

Enduring Impact and Legacy

Thomas Moran's impact on American art and culture is multifaceted and enduring. His most tangible legacy lies in his contribution to the creation of the National Park system. His paintings of Yellowstone, particularly The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, provided crucial visual persuasion that led Congress to establish the park. This act set a precedent for preserving other areas of natural beauty, and Moran's subsequent paintings of the Grand Canyon and other Western sites continued to foster public appreciation for these landscapes and support for their protection. He became known as the "Father of the National Parks" alongside figures like John Muir.

Artistically, Moran brought the American West into the mainstream of American landscape painting. His work defined the visual iconography of places like Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon for millions who had never seen them. His dramatic, color-filled canvases offered a romanticized yet compelling vision of the West as a land of sublime beauty and limitless possibility, contributing to the burgeoning "Myth of the West" in the American imagination during a period of westward expansion and national identity formation. His technical mastery, particularly his handling of light and color influenced by Turner, brought a new level of vibrancy and atmospheric depth to American landscape art.

Moran achieved significant fame and financial success during his lifetime. His major paintings commanded high prices, and his work was widely reproduced through engravings and etchings, making his imagery accessible across society. He was celebrated both in the United States and abroad, exhibiting his work internationally. While the taste for large-scale Romantic landscapes waned with the rise of Modernism in the early 20th century, Moran's reputation has since been firmly re-established. His works are held in major museums across the country and are considered essential examples of 19th-century American art. His paintings continue to captivate viewers with their technical brilliance and their powerful evocation of America's natural wonders.

Later Life and Continued Creativity

Even after achieving national fame with his Western epics, Thomas Moran remained a prolific and active artist for decades. While the West remained a recurring subject, his artistic interests were broad. Following his 1873 trip with Powell, he traveled again to Europe, notably visiting Venice. The city's unique combination of architecture, water, and light captivated him, much as it had captivated Turner before him. He purchased a gondola to use as a studio prop and produced numerous paintings and etchings of Venetian scenes throughout his career, showcasing his versatility and his enduring love for atmospheric effects and rich color, applied now to an Old World subject.

In 1884, Moran and his wife Mary Nimmo Moran established a home and studio in East Hampton, Long Island, New York. This coastal environment provided new subjects, and he painted many views of the Long Island shore, capturing the different moods of the Atlantic. However, he continued to make trips West well into his later years, revisiting familiar locations like the Grand Canyon and exploring new areas. He also traveled to Mexico, seeking out new landscapes and subjects. His later Western paintings often maintained the grandeur of his earlier work but sometimes showed a looser brushwork or a more intimate focus.

In 1916, following his wife's death in 1899 and seeking a warmer climate, Moran moved to Santa Barbara, California. He remained active there, continuing to paint landscapes inspired by the California coast and the enduring memories of his Western adventures. He worked almost until his death, demonstrating a lifelong dedication to his art. Thomas Moran passed away in Santa Barbara on August 25, 1926, at the age of 89. He left behind a vast body of work and an indelible mark on American art and the nation's relationship with its landscape.

Conclusion: A Legacy in Landscape

Thomas Moran's life and work represent a remarkable journey, from an immigrant boy in industrial England to one of America's most celebrated landscape painters. His art captured the unique majesty of the American West at a crucial moment in the nation's history, shaping public perception and contributing significantly to the preservation of these natural wonders. Influenced by European masters like Turner but forging a distinctly American vision, Moran combined technical virtuosity with a Romantic sensibility to create images of enduring power and beauty. His monumental canvases of Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon remain icons of American art, while his broader body of work reveals a versatile artist constantly exploring the effects of light, color, and atmosphere across diverse landscapes. More than just a painter of mountains and canyons, Thomas Moran helped America visualize its own grandeur and recognize the importance of its natural heritage. His legacy lives on not only in museums and galleries but also in the protected landscapes he so passionately depicted.