Peter Moran, a distinguished figure in nineteenth-century American art, carved a unique niche for himself as a master etcher, particularly celebrated for his evocative depictions of animals and the sprawling landscapes of the American West. Born in Bolton, Lancashire, England, on March 4, 1841, he was part of an exceptionally talented artistic family. His journey from the industrial heartland of England to the nascent art scene of Philadelphia, and subsequently to the rugged terrains of the American frontier, shaped a body of work that remains significant for its technical skill, its historical insight, and its contribution to the American Etching Revival.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Philadelphia

The Moran family's relocation to the United States in 1844, when Peter was merely three years old, proved to be a pivotal moment. They settled in Philadelphia, a city rapidly establishing itself as a cultural and artistic hub in America. This environment would nurture the talents of Peter and his elder brothers, Thomas Moran, who would become famous for his grand canvases of the American West, and Edward Moran, who gained renown as a marine painter. A younger brother, John, also pursued photography. The collective artistic energy within the Moran household undoubtedly played a crucial role in Peter's early development.

At the age of sixteen, around 1857, Peter Moran embarked on his formal artistic training, not initially in a fine art academy, but as an apprentice at the Philadelphia lithographic firm of Herline & Hensel. This early immersion in the world of printmaking, primarily focused on commercial work such as advertisements, provided him with a foundational understanding of graphic processes. However, his aspirations lay beyond commercial lithography. He soon began to study painting and etching more seriously under the direct guidance of his accomplished elder brothers, Edward and Thomas. Their mentorship was invaluable, offering him practical skills and artistic direction.

Philadelphia itself was a stimulating environment. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, one of the oldest art institutions in the country, was a central feature, and artists like Thomas Sully, a leading portraitist, had long established the city's artistic credentials. While Moran's direct tutelage came from his brothers, the broader artistic currents of the city, including a growing appreciation for landscape and genre scenes, would have informed his evolving perspective.

European Sojourn and Formative Influences

In 1863, seeking to broaden his artistic horizons and expose himself to European masters, Peter Moran traveled to England. This was a common practice for ambitious American artists of the era, who looked to Europe, particularly London and Paris, for advanced training and inspiration. During his time in England, Moran was significantly influenced by several prominent artists, most notably Sir Edwin Landseer, the celebrated Victorian painter of animals. Landseer's dramatic and often sentimental portrayals of stags, dogs, and other creatures, rendered with meticulous detail, offered a powerful example of how animal subjects could be elevated to high art.

Another key influence was Rosa Bonheur, a French artist who had achieved international fame for her realistic and unsentimental depictions of animals, particularly horses and cattle. Bonheur's success as a female artist in a male-dominated field was remarkable, and her commitment to anatomical accuracy and direct observation of nature resonated with Moran's own burgeoning interests. Constant Troyon, a prominent member of the French Barbizon School, also left an impression. Troyon's landscapes, often featuring cattle, were admired for their atmospheric qualities and their sensitive portrayal of rural life. These European encounters helped solidify Moran's focus on animal and landscape subjects and refined his technical approach. He absorbed the European emphasis on careful observation and skilled draughtsmanship, elements that would become hallmarks of his later etchings.

The artistic climate in London at the time was vibrant. The Royal Academy exhibitions were major events, and artists like John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, key figures of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, were still influential, championing truth to nature. While Moran's style did not directly align with Pre-Raphaelitism, the prevailing emphasis on detailed realism in British art would have reinforced his own inclinations.

The Ascendance of an Etcher

Upon his return to Philadelphia in 1867, Peter Moran increasingly dedicated himself to the art of etching. This medium, which involves incising a design into a metal plate from which prints are made, was experiencing a significant revival in both Europe and America during the latter half of the nineteenth century. The "Etching Revival" championed the expressive potential of the etched line and the unique qualities of the printed image, distinguishing original prints from mere reproductions.

Moran quickly established himself as a skilled and sensitive etcher. His technical proficiency allowed him to capture a wide range of textures and atmospheric effects, from the rough hide of a bison to the delicate light of a sunset. He was not merely a technician, however; his etchings were imbued with a deep appreciation for his subjects. He often printed his own plates, ensuring meticulous quality control over each impression, a practice common among dedicated "painter-etchers" of the period.

His commitment to the medium extended beyond his personal practice. Peter Moran was a key figure in promoting etching as a fine art form in America. He was a founder of the Philadelphia Society of Etchers and served as its president for an impressive twenty-three years. He also held the presidency of the New York Etching Club at one point, and was an active member of the Society of American Etchers. These organizations played a vital role in fostering a community of etchers, organizing exhibitions, and educating the public about the art form. His leadership underscored his dedication to elevating the status of American printmaking. Artists like James Abbott McNeill Whistler, an American expatriate, and Seymour Haden, Whistler's brother-in-law and a leading British etcher, were instrumental in popularizing etching internationally, and Moran's efforts in Philadelphia mirrored this broader movement.

Master of Animal and Landscape Art

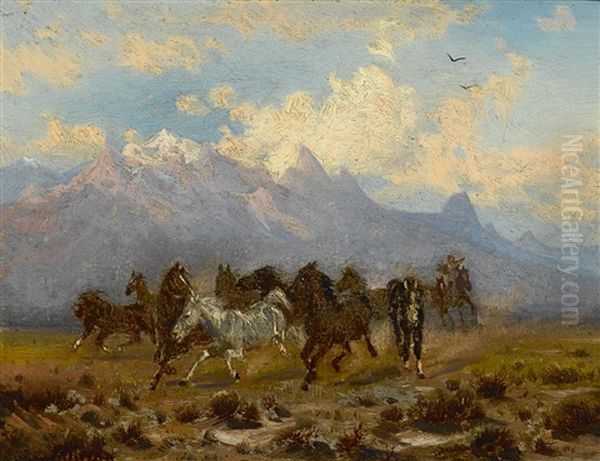

Peter Moran's oeuvre is characterized by its focus on animals and landscapes. He possessed an acute ability to observe and render animal anatomy and behavior, bringing a sense of life and authenticity to his subjects. His depictions were rarely sentimental in the overt manner of some Victorian animal painters; instead, they conveyed a quiet dignity and a deep understanding of the creatures he portrayed. Cattle, horses, sheep, and bison were frequent subjects, often shown within their natural environments.

His landscapes, too, were marked by a keen observational skill and a sensitivity to atmosphere. While his brother Thomas became famous for dramatic, panoramic vistas of the West, Peter's landscapes were often more intimate, focusing on specific qualities of light, terrain, and vegetation. His work often reflected a pastoral sensibility, a nostalgia for rural life that was increasingly felt in an era of rapid industrialization and urbanization. One of his notable works, "Return of the Herd," exemplifies his skill in combining animal and landscape elements, creating a harmonious and evocative scene. Another piece, "Landscape of Florida," showcases his ability to capture the unique atmosphere of different American regions.

His etchings were widely disseminated, partly through publications like the American Art Review, which brought original prints to a broader audience. This journal, edited by Sylvester Rosa Koehler, was a crucial platform for the Etching Revival in the United States, and Moran was a frequent contributor. His works were praised for their technical excellence and their authentic portrayal of American scenes. Other prominent American etchers of the time included Stephen Parrish and R. Swain Gifford, who also contributed to the growing body of American printmaking.

Chronicler of the American West and its Native Peoples

A significant aspect of Peter Moran's career was his engagement with the American West. Inspired by a burgeoning national interest in the frontier and perhaps by his brother Thomas's celebrated expeditions, Peter Moran made several trips to the western territories. He traveled to New Mexico, Arizona, and Wyoming, regions that were still largely untamed and offered a wealth of new subjects for an artist.

His western journeys were not merely sightseeing tours; they were opportunities for deep immersion and artistic documentation. In 1864, he made a notable trip to New Mexico, where he became one of the first non-Native artists to extensively document the life and culture of the Pueblo Indians. He returned to New Mexico and Arizona in the 1870s and 1880s, creating numerous sketches, paintings, and, importantly, etchings that captured the unique adobe architecture, the daily activities, and the ceremonial life of the Pueblo peoples. His depictions of Acoma Pueblo, Laguna Pueblo, and other ancient settlements are valuable historical and artistic records.

Moran's interest in Native American ethnology was profound. His work in this area was recognized officially when, in 1890, he was appointed as an official artist for the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. In this capacity, he was involved in the Indian census work, further deepening his engagement with Native communities. His portrayals of Native Americans were generally sympathetic and respectful, aiming for accuracy rather than romanticization, which set him apart from some contemporary depictions. He sought to capture the dignity and resilience of these cultures at a time of immense pressure and change. His work can be seen in the context of other artists documenting the West, such as Albert Bierstadt, whose grand landscapes often included Native figures, or earlier artists like George Catlin and Karl Bodmer, who had created extensive visual records of Plains Indian cultures. However, Moran's focus on the Pueblo peoples and his chosen medium of etching gave his contribution a distinct character.

The Moran Artistic Dynasty

Peter Moran's artistic journey cannot be fully understood without acknowledging the profound influence of his family. His elder brother, Thomas Moran (1837-1926), became one of America's most celebrated landscape painters, particularly known for his spectacular canvases of Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon, which played a role in the establishment of National Parks. Thomas was also a skilled etcher and illustrator. Edward Moran (1829-1901) established himself as a leading marine painter, capturing the power and beauty of the sea.

The artistic talent extended to Thomas Moran's wife, Mary Nimmo Moran (1842-1899). She became a highly respected etcher in her own right, known for her expressive landscapes, particularly scenes of Long Island and later, East Hampton. She was one of the few women elected to the New York Etching Club and the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers in London. The close artistic relationship between Peter, Thomas, and Mary Nimmo Moran, all accomplished etchers, suggests a supportive and creatively stimulating family environment. They likely shared techniques, critiques, and encouragement, contributing to each other's development and success in the field of printmaking. This familial artistic cluster is relatively unique in American art history.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Peter Moran worked during a dynamic period in American art. The Hudson River School, with artists like Frederic Edwin Church and Sanford Robinson Gifford, had established landscape painting as a dominant genre, celebrating the American wilderness. While Moran's generation moved towards different stylistic concerns, the legacy of detailed observation of nature persisted.

In Philadelphia, Thomas Eakins, a contemporary, was pursuing a path of uncompromising realism, often challenging conventional tastes. While Eakins's focus was primarily on portraiture and scenes of modern life, his dedication to anatomical accuracy and direct observation shared some common ground with the Moran brothers' approach to their respective subjects. The city also boasted other skilled artists like William Trost Richards, known for his meticulous marine paintings and watercolors.

The Etching Revival, as mentioned, connected Moran to a broader international community. Besides Whistler and Haden, French artists like Charles Meryon and Félix Bracquemond were influential figures. In America, the movement fostered a new appreciation for printmaking as an original art form, and artists like Frank Duveneck and William Merritt Chase also produced notable etchings, though they were primarily known as painters. Moran's consistent dedication to etching throughout his career made him a central figure in the American chapter of this revival.

Later Years, Legacy, and Personal Glimpses

Peter Moran continued to work and exhibit throughout his life, maintaining his commitment to his chosen subjects and medium. His etchings found their way into numerous public and private collections, valued for their artistic merit and their depiction of American life and landscape. He passed away in Philadelphia on November 9, 1914, leaving behind a significant body of work.

His legacy rests on several pillars. He was a master technician in etching, contributing significantly to the technical and artistic development of the medium in the United States. His depictions of animals are among the finest in American art, characterized by their accuracy and empathy. His work in the American West, particularly his documentation of Pueblo Indian life, provides an invaluable historical and cultural record. Furthermore, his role as a founder and long-time president of the Philadelphia Society of Etchers highlights his importance as an organizer and advocate for the arts.

While much of his public persona revolved around his art, glimpses from the provided information suggest a personal life that valued close relationships. He was reportedly close to the Fiaschi family and cherished a friendship with a Dr. H. M. Molesworth. His memoirs, though said to be sparse on personal details, apparently revealed his deep love for art and his concern for societal changes, likely reflecting the transformations he witnessed during his lifetime, from the Civil War era through the Gilded Age and into the early twentieth century.

Peter Moran's art offers a window into nineteenth-century America – its landscapes, its wildlife, its Native cultures, and its artistic aspirations. As an artist who skillfully balanced detailed realism with expressive power, and who dedicated himself to the demanding art of etching, he holds an enduring place in the annals of American art history. His contributions, both as a creator and as a proponent of his chosen medium, ensured that the art of etching flourished in America, leaving a rich legacy for future generations of artists and art lovers.