Carl Oscar Borg stands as a significant figure in the annals of American Western art. A Swedish immigrant who embraced the landscapes and cultures of his adopted homeland, Borg translated the vastness of the American West, particularly the sun-drenched Southwest, into compelling visual narratives. His work, spanning multiple media, captured not only the physical grandeur of the region but also the spirit of its Native American inhabitants, leaving behind a legacy rich in artistic merit and historical documentation. His journey from a humble background in rural Sweden to becoming a celebrated artist in California is a testament to his talent, perseverance, and unique vision.

From Sweden to the World: Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Carl Oscar Borg was born on March 3, 1879, in Dals-Grinstad, a parish in the Dalsland province of Sweden. His origins were modest; born into a poor family, the prospects for formal art education were limited. Yet, an innate artistic drive manifested early. Largely self-taught, Borg honed his observational skills and rudimentary techniques amidst the landscapes of his youth. Financial necessity dictated a practical path initially.

At the age of fifteen, Borg began an apprenticeship as a house painter. This trade, while seemingly distant from fine art, likely provided him with a foundational understanding of pigments, surfaces, and application techniques. It was a start, a way to engage with color and form, albeit in a utilitarian context. However, the young Borg harbored ambitions that extended far beyond the borders of his homeland and the confines of decorative painting.

Seeking broader horizons and opportunities, Borg made a pivotal move around the age of twenty, relocating to London, England. There, he found work that edged closer to his artistic aspirations, securing employment as a scene painter for theaters. This experience immersed him in the creation of large-scale illusions, demanding skills in perspective, color mixing, and rapid execution – valuable training for any aspiring artist. It was also in London that he reportedly received guidance from the portrait and marine painter George Johnstone, offering a crucial, albeit perhaps informal, step in his artistic education.

The Lure of America: Immigration and California Dreams

The turn of the century marked another significant chapter in Borg's life. In 1901, drawn by the promise and potential of the New World, he immigrated to the United States. Like many immigrants, his initial period was marked by practical labor. He first landed on the East Coast, where he likely continued working trades learned earlier, such as house and furniture painting, to support himself.

However, the magnetic pull of the West Coast, particularly California, soon proved irresistible. By 1902, Borg had made his way across the continent and settled in California. This state, with its burgeoning art scene, diverse landscapes, and growing reputation, would become his home base and the primary inspiration for much of his life's work. He initially found work that utilized his scene-painting skills, reportedly working for the burgeoning motion picture industry.

By 1904, Borg was living and working in Santa Barbara, a city whose scenic beauty and Mediterranean light attracted many artists. This period was crucial for his establishment as a fine artist. He began to focus more intently on easel painting, capturing the coastal landscapes and missions that defined the region. His talent quickly gained recognition, and in 1905, he held his first solo exhibition, a significant milestone marking his public emergence as a professional artist in California.

Formal Studies and Developing Vision

While largely self-taught initially, Borg recognized the value of formal training to refine his technique and broaden his artistic understanding. Encouraged by patrons, including Phoebe Hearst (mother of William Randolph Hearst), who recognized his potential, Borg traveled to Europe. In 1906, he spent time studying art in Paris and Rome. This exposure to the masterpieces of European art and the academic traditions, though perhaps brief, undoubtedly enriched his perspective and technical facility.

Upon returning to California, Borg continued to develop his distinctive style. He formed important friendships within the vibrant California art community. A key figure in his development was William Wendt, a preeminent California Impressionist landscape painter. Wendt became a friend and mentor, and his influence can be discerned in Borg's handling of light and landscape, although Borg forged his own unique path, less strictly Impressionistic and more focused on the specific character of the Western environment.

Borg's artistic toolkit was notably diverse. He became proficient not only in oil painting but also in watercolor, etching, and woodblock printing. This mastery of multiple media allowed him to explore different aesthetic possibilities and capture varied aspects of his subjects, from the broad sweep of a desert vista in oil to the intricate details of a Native American portrait in etching.

The Enchantment of the Southwest

A defining moment in Carl Oscar Borg's artistic journey occurred in 1916. Sponsored by Phoebe Hearst, he embarked on his first extensive trip to the American Southwest, visiting the lands of the Hopi and Navajo peoples in Arizona and New Mexico. This experience was transformative. Borg was profoundly captivated by the stark beauty of the desert landscapes, the dramatic canyons, the unique quality of light, and, crucially, the rich cultural traditions of the Native American tribes he encountered.

This journey ignited a lifelong passion. The Southwest became a central, recurring theme in his work. He returned numerous times over the following decades, immersing himself in the environment and developing deep respect and friendships with the Hopi and Navajo people. He learned about their customs, ceremonies, and worldview, striving to depict them with accuracy and sensitivity, avoiding the romanticized stereotypes prevalent at the time.

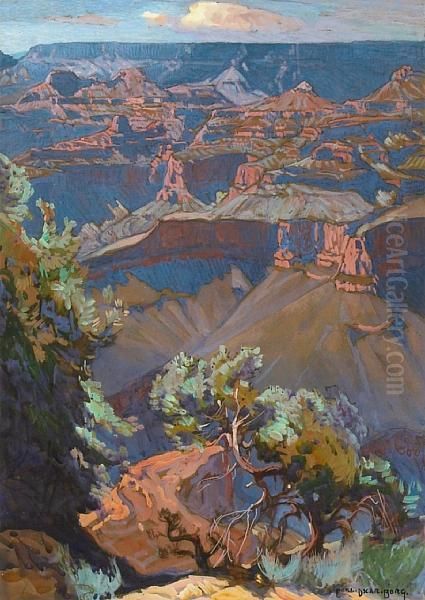

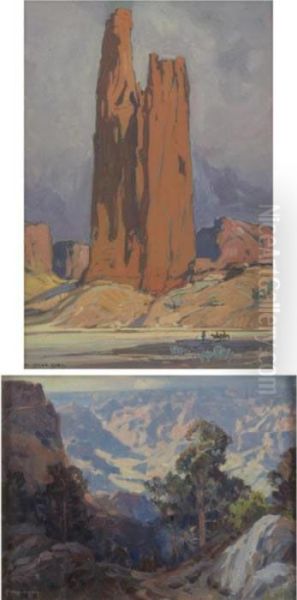

His paintings from this period often feature iconic Southwestern landscapes – the Grand Canyon, Monument Valley, desert mesas under vast skies. He was particularly adept at capturing the interplay of light and shadow across the arid terrain, conveying both its harshness and its sublime beauty. His depictions of Native American life went beyond mere ethnographic recording; they often conveyed a sense of dignity, resilience, and spiritual connection to the land.

Masterworks and Signature Themes

Carl Oscar Borg's oeuvre is rich with memorable images of the West. One of his most recognized works is The Silence of the Evening. This painting depicts several Hopi figures perched on a cliff edge, gazing out at a dramatic sunset over the vast landscape. It masterfully combines landscape painting with figurative elements, evoking a sense of quiet contemplation, the profound connection between the people and their ancestral land, and the overwhelming scale of nature compared to humanity.

His depictions of the Grand Canyon are also highly regarded. He painted the Canyon from various viewpoints and under different light conditions, capturing its immense scale, complex geology, and ever-shifting colors. These works stand alongside those of earlier masters like Thomas Moran, offering a distinct, early 20th-century perspective on this natural wonder. Borg's interest seemed to lie not just in the spectacle but also in the feeling of timelessness and the raw power of nature embodied by the Canyon.

Beyond landscapes, his portraits and depictions of Native American ceremonies are invaluable. Works featuring Hopi kachina dances or Navajo weavers provide glimpses into cultural practices. He approached these subjects with respect, often focusing on the details of traditional attire, the intensity of the participants, and the sacredness of the event. These works became particularly significant as records of cultures undergoing rapid change.

Connections and Collaborations: An Artist Among Peers

Borg was an active participant in the art world of his time, forging significant relationships with fellow artists. His closest artistic friendship was arguably with Edward Borein, another prominent Western artist based in Santa Barbara, known especially for his etchings and watercolors of cowboys and Native American life. Borg and Borein shared studios at times, traveled together on sketching trips throughout the West, and even taught art classes together. Their shared interest in Western subjects created a strong bond, though their styles remained distinct.

His connection with William Wendt provided mentorship and camaraderie within the California landscape painting tradition. Borg also moved within circles that included other notable California artists, likely interacting with figures associated with the California Impressionist movement, such as Guy Rose or Granville Redmond, even if his style diverged. His focus on the Southwest also placed his work in dialogue with that of the Taos Society of Artists, including painters like E. Irving Couse and Joseph Henry Sharp, who were similarly dedicated to depicting Native American life, albeit often with a different aesthetic.

Later in his career, Borg collaborated on projects that combined art with historical narrative. In 1936, he worked with the artist Millard Sheets and the historian Dr. Herbert Eugene Bolton (often cited as Eugene B. Dolley/Bolton in some sources related to Borg) to illustrate the book Cross, Sword and Gold Pan, a history of California. This project showcased his ability to apply his artistic skills to historical subjects. That same year, he published The Great Southwest, a collection of his own etchings, further solidifying his reputation as a chronicler of the region. His work inevitably invites comparison with other great Western artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, though Borg's focus was perhaps less on dramatic action and more on landscape and cultural representation. He also shared thematic territory with contemporaries like Maynard Dixon and Fernand Lungren, who were also captivated by the light and forms of the desert West.

Educator and Advocate

Carl Oscar Borg's contribution to the art world extended beyond his own creations. He was dedicated to sharing his knowledge and passion through teaching. He served as an instructor at the California Art Institute (formerly the Otis Art Institute) in Los Angeles from 1918 to 1924. Later, he taught at the Santa Barbara School of the Arts from 1924 to 1935. Through these roles, he influenced a generation of younger artists, passing on his technical skills and his deep appreciation for the American West.

His work itself served as a form of advocacy. In an era often marked by misunderstanding and prejudice towards Native American cultures, Borg's sensitive and dignified portrayals offered a valuable counter-narrative. His landscape paintings, particularly those of areas like the Grand Canyon, implicitly carried an environmental message, celebrating the beauty of the natural world and, by extension, the importance of its preservation. His deep friendships with Hopi and Navajo individuals further underscore his commitment to cross-cultural understanding.

Recognition and Later Years

Throughout his career, Carl Oscar Borg received significant recognition for his work. He exhibited widely across the United States and in Europe. An early notable success was winning a silver medal at the prestigious Panama-Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1915. His paintings and prints were acquired by major institutions, including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the Library of Congress, and university collections, ensuring the preservation and accessibility of his work.

He maintained his studio in Santa Barbara for many years, which remained his primary residence, though he continued his travels, including return trips to Sweden. He remained active as an artist, continuing to explore his beloved Western themes. His reputation solidified as one of the key figures in early 20th-century Western American art.

Carl Oscar Borg passed away in Santa Barbara, California, on May 8, 1947. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its artistic quality, its historical significance, and its heartfelt portrayal of the American West.

Legacy of a Swedish Visionary

Carl Oscar Borg's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he demonstrated exceptional skill across various media, creating a body of work characterized by strong composition, nuanced color, and evocative atmosphere. He successfully blended elements of realism with a romantic sensibility, capturing both the objective details and the subjective feeling of the Western landscapes and peoples he depicted.

As a chronicler of the Southwest, his work provides invaluable visual documentation of Native American life and the region's natural beauty during a period of significant transition. His respectful and insightful portrayals of the Hopi and Navajo stand as an important contribution to the representation of Indigenous cultures in American art.

As an immigrant artist, Borg brought a unique perspective to American subjects. His European background may have informed his appreciation for the vast scale and distinct light of the American West, allowing him to see and interpret it in a fresh way. He successfully navigated the journey from outsider to insightful interpreter, becoming a quintessential painter of the American West. His life and work remain an enduring example of artistic dedication and cross-cultural engagement.