Thomas Patch (1725–1782) stands as a unique and somewhat enigmatic figure in the annals of 18th-century British art. An expatriate who spent the majority of his productive life in Italy, first in Rome and then predominantly in Florence, Patch carved out a distinctive niche for himself. He is primarily remembered for his satirical caricature groups of British Grand Tourists, his detailed vedute (view paintings) of Florence, and, perhaps most significantly for art history, his pioneering engravings after early Italian Renaissance masters like Masaccio. His life was as colourful as his paintings, marked by talent, eccentricity, and a certain notoriety that followed him from Rome to Florence.

Early Life and Roman Sojourn

Born in Exeter, England, in 1725, Thomas Patch's early artistic training remains somewhat obscure. It is known, however, that by 1747 he had made his way to Rome, the ultimate destination for any aspiring artist or cultured gentleman of the era. In Rome, he is believed to have studied under Claude-Joseph Vernet, a renowned French landscape painter whose Italianate views were highly sought after. Vernet's influence can be discerned in Patch's later topographical works, particularly in his handling of light and atmosphere.

Rome in the mid-18th century was a vibrant artistic melting pot. Patch would have been aware of, and likely interacted with, a host of other artists catering to the burgeoning Grand Tour market. Figures such as Pompeo Batoni, the leading portraitist of visiting milordi, Anton Raphael Mengs, a proponent of Neoclassicism, and the visionary etcher Giovanni Battista Piranesi, whose dramatic views of Roman antiquities captivated Europe, all contributed to the city's artistic ferment. Patch, however, was already developing his own particular brand of art, focusing on group caricatures that poked gentle, and sometimes not-so-gentle, fun at his fellow countrymen.

His time in Rome, however, came to an abrupt and scandalous end in 1755. Patch was expelled from the Papal States by the authorities. The exact reasons remain a subject of some debate among historians, with suggestions ranging from indiscreet homosexual activities, which were severely proscribed, to alleged Jacobite sympathies or financial impropriety. Whatever the precise cause, this expulsion forced him to relocate, and he chose Florence as his new base.

The Florentine Years: A New Chapter

Arriving in Florence in 1755, Thomas Patch quickly established himself within the Anglo-Florentine community. This community was presided over by Sir Horace Mann, the British envoy to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany for over four decades. Mann became a crucial patron and friend to Patch, and his residence, the Palazzo Manetti, was a central hub for British visitors. Patch found a ready market for his talents among the steady stream of Grand Tourists passing through the city.

Florence, though perhaps not possessing the overwhelming ancient grandeur of Rome, offered its own rich artistic and cultural heritage, particularly from the Renaissance. It was also a key stop on the Grand Tour itinerary, and Patch capitalized on this. He became a familiar, if somewhat eccentric, figure in the city, known for his wit, his artistic skill, and his often flamboyant personality. He lived and worked in Florence for the remainder of his life, dying there in 1782.

His studio became a popular port of call for tourists, eager to be immortalized in one of his distinctive caricatures or to purchase a view of the Arno as a sophisticated souvenir. He also engaged with other artists in Florence, including Johan Zoffany, another painter popular with the Grand Tourists, though their relationship was sometimes marked by rivalry. Joshua Reynolds, the preeminent English portrait painter, visited Florence and was painted by Patch, indicating a degree of mutual respect or at least professional interaction.

Artistic Output: Caricatures and Conversation Pieces

Thomas Patch's caricatures are arguably his most distinctive contribution to 18th-century art. These were typically group portraits, often set in recognizable Florentine locations or interiors, depicting British Grand Tourists and local cognoscenti. Unlike the savage political satire of artists like William Hogarth, Patch's caricatures were generally more social and light-hearted, though they often contained pointed observations about the affectations and pretensions of his subjects.

His method involved exaggerating the physical features and characteristic poses of individuals, often placing them in amusing or revealing juxtapositions. The bodies in his caricatures could be somewhat formulaic, almost like mannequins, but the heads were highly individualized, capturing a recognizable likeness despite the distortion. These works served as witty mementos of the Grand Tour experience, shared among a relatively small and interconnected social circle.

Notable examples of his caricature groups include "The Cognoscenti" (also known as "A Group of Punchinellos"), "A Gathering of Dilettanti at Sir Horace Mann's House," and various untitled groups depicting gentlemen admiring statues, paintings, or engaging in learned discussion. These paintings provide invaluable visual records of the personalities, fashions, and social rituals of the Grand Tour. They also reveal Patch's keen eye for human folly and his ability to translate social observation into humorous art. He often included himself in these compositions, sometimes as a detached observer, other times as an active participant in the scene.

Artistic Output: Vedute and Cityscapes

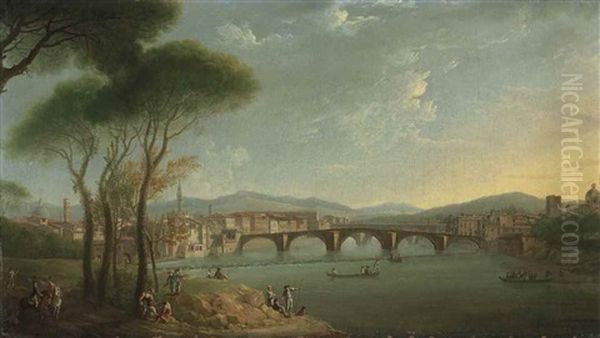

Alongside his caricatures, Thomas Patch was a proficient painter of vedute, or view paintings. His primary subject in this genre was the city of Florence itself, particularly views along the River Arno, often featuring the Ponte Santa Trinita or the Ponte Vecchio. These paintings were highly popular with Grand Tourists, offering them a tangible and aesthetically pleasing record of their visit to the Tuscan capital.

Patch's vedute demonstrate an attention to topographical accuracy, combined with an ability to capture the particular light and atmosphere of Florence. While influenced by artists like Vernet and perhaps Canaletto, whose Venetian views set the standard for the genre, Patch developed his own recognizable style. His Florentine cityscapes are often characterized by a slightly cooler palette and a less idealized, more workaday depiction of city life compared to some of his contemporaries.

Works such as "View of the Arno with the Ponte Santa Trinita" or "Florence: A View of the Arno by Day" showcase his skill in rendering architecture, water, and the bustling activity of the city. These paintings were not merely picturesque souvenirs; they also reflected the 18th-century appreciation for classical proportion, urban order, and the historical resonance of Italian cities. Patch produced several versions of these views, sometimes in pairs depicting the same scene by day and by night, or during different seasons, demonstrating his versatility and his understanding of the market's desires.

Artistic Output: Engravings and the Renaissance Revival

Perhaps Thomas Patch's most enduring contribution to art history lies in his work as an engraver, particularly his efforts to reproduce and disseminate images of early Italian Renaissance art. At a time when High Renaissance artists like Raphael and Michelangelo, and later Baroque masters, dominated artistic taste, the achievements of 14th and 15th-century painters were often overlooked or undervalued.

Patch undertook the ambitious project of engraving the frescoes by Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence. His series, "The Life of Masaccio," published in 1770, was a landmark achievement. These engravings made Masaccio's powerful and innovative compositions accessible to a wider audience outside of Italy, including artists and scholars. This was crucial for the re-evaluation of Masaccio's pivotal role in the development of Renaissance painting, particularly his mastery of perspective, naturalism, and human emotion.

In addition to Masaccio, Patch also produced engravings after frescoes by Giotto in the Peruzzi and Bardi Chapels in Santa Croce, Florence, and works by other early masters like Fra Bartolommeo. These publications, often accompanied by biographical information, played a significant role in the burgeoning interest in the "primitives" of Italian art, an interest that would gain further momentum in the 19th century with the Pre-Raphaelites and art historians like John Ruskin. Patch's efforts helped to broaden the canon of appreciated art and laid groundwork for a more comprehensive understanding of Italian art history. His dedication to this task suggests a genuine scholarly interest beyond mere commercial opportunism.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Thomas Patch's artistic style was multifaceted, adapting to the different genres in which he worked. In his caricatures, his style is defined by deliberate exaggeration and a focus on physiognomy. He employed a relatively linear approach for the figures, often with flat areas of colour, which emphasized the comical distortions of faces and postures. The compositions, while seemingly informal, were carefully arranged to create humorous interactions and narratives within the group.

For his vedute, Patch adopted a more naturalistic style, in line with the conventions of topographical painting. He paid close attention to architectural detail, perspective, and the play of light and shadow. His brushwork in these paintings was generally tighter and more controlled than in his caricatures, aiming for a faithful yet aesthetically pleasing representation of the Florentine urban landscape. He often used a camera obscura to aid in the accuracy of his city views, a common practice among veduta painters of the period.

As an engraver, Patch demonstrated considerable technical skill. His engravings after Masaccio and Giotto aimed to translate the monumental quality and narrative clarity of the original frescoes into the linear medium of print. He utilized a combination of etching and engraving techniques to convey form, texture, and tonal variation. While not always perfectly faithful to the nuances of the originals by modern standards, his prints were groundbreaking for their time and served their purpose of popularizing these seminal works. His dual practice as a painter and printmaker allowed him to reach different segments of the art market and to pursue both commercial and scholarly interests.

Patch and His Contemporaries

Thomas Patch's career was interwoven with a diverse cast of characters, from fellow artists to patrons and the subjects of his art. His teacher in Rome, Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714-1789), undoubtedly shaped his approach to landscape and view painting. In the competitive Roman art scene, he would have been aware of the successes of Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787), whose grand portraits of tourists set a high bar, and the more austere Neoclassicism of Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-1779). The powerful etchings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) also formed a significant part of the artistic backdrop.

In Florence, his relationship with Sir Horace Mann (1706-1786) was paramount, providing him with social access and commissions. He encountered Johan Zoffany (1733-1810), whose "conversation pieces" and depictions of art collections like the "Tribuna of the Uffizi" sometimes overlapped with Patch's milieu, leading to a degree of professional rivalry. The visit of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) to Florence and his sitting for a caricature portrait by Patch is a notable interaction. Another British landscape painter active in Italy around the same time was Richard Wilson (1714-1782), whose classical landscapes offered a different vision of the Italian scene.

Patch's engravings brought him into a different kind of dialogue with artists of the past, most notably Masaccio (1401-1428) and Giotto di Bondone (c. 1267-1337). By reproducing their work, he engaged with their artistic legacies and helped to shape their posthumous reputations. Other artists whose works he engraved included Fra Bartolommeo (1472-1517). One might also consider figures like Nathaniel Dance-Holland (1735-1811), who also produced caricatures of Grand Tourists in Rome, as a contemporary working in a similar vein, or Thomas Jenkins (1722-1798), a prominent dealer, banker, and antiquarian in Rome who facilitated many Grand Tourists' acquisitions, as part of the broader ecosystem Patch inhabited. Even the architect William Chambers (1723-1796), a key figure in British Neoclassicism, was caricatured by Patch during his time in Italy.

Anecdotes and Character

Thomas Patch was by all accounts a memorable character, and several anecdotes illuminate his personality. His abrupt expulsion from Rome in 1755 is the most dramatic episode, hinting at a life lived somewhat on the edge of social convention. While the precise reasons remain unconfirmed, the whiff of scandal certainly added to his notoriety.

In Florence, he was known for his wit and sociability, but also for a certain irascibility and eccentricity. He was a keen collector of curiosities and owned a pet dog, a pug, which frequently appeared in his caricature paintings, sometimes mimicking the poses of the human subjects or serving as a humorous counterpoint. This inclusion of his pet adds a personal and whimsical touch to his works.

There are accounts of his occasionally sharp tongue and his willingness to satirize even his patrons, albeit usually within the bounds of acceptable social humor. His self-portraits, often incorporated into his group caricatures, depict him with a knowing, slightly mischievous expression, suggesting an artist who was very much aware of the absurdities of the world he observed and recorded. His long-term residence in Florence, despite being an expatriate, indicates a deep attachment to the city and its culture, or perhaps a pragmatic acceptance of where his artistic bread was best buttered.

Later Life and Legacy

Thomas Patch continued to live and work in Florence until his death on April 30, 1782. He was buried in the Old English Cemetery in Livorno, a common practice for non-Catholics in Tuscany at the time. In his later years, he seems to have focused more on his engraving projects and his vedute, although he continued to produce caricatures.

His legacy is threefold. Firstly, his caricatures provide an invaluable and amusing visual record of the Grand Tour phenomenon and the Anglo-Florentine society of the mid-18th century. They capture the personalities, fashions, and social interactions of a specific class at a specific historical moment with a unique blend of observation and satire. These works influenced later caricaturists and remain important documents for social historians.

Secondly, his vedute of Florence contribute to the rich tradition of Italian view painting. While perhaps not as celebrated as those of Canaletto or Bellotto, they are accomplished works that capture the enduring charm of the Tuscan capital and were highly prized by those who commissioned or purchased them.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly from an art historical perspective, his engravings after Masaccio, Giotto, and other early Renaissance masters were pioneering. They played a crucial role in disseminating knowledge of these artists and contributed significantly to the revival of interest in the "primitive" Italian painters, a movement that would have profound implications for 19th-century art and art history. He helped to broaden the established canon and encouraged a more nuanced understanding of the development of Western art.

Historical Position and Evaluation

In the broader sweep of art history, Thomas Patch occupies a specific and interesting niche. He was not a revolutionary innovator in the grand sense, like a Caravaggio or a Picasso, but he was a highly skilled and perceptive artist who responded intelligently to the demands and opportunities of his time and place. His position is primarily defined by his role as a chronicler and satirist of the Grand Tour, a cultural phenomenon of immense importance in the 18th century.

His caricatures are significant as early examples of social satire in group portraiture, moving beyond the purely political. They offer a window into the world of the British elite abroad, their intellectual pretensions, their social rituals, and their individual eccentricities. As such, they are invaluable historical documents as much as works of art.

His vedute, while more conventional, are accomplished examples of the genre and demonstrate his technical proficiency as a painter. They catered to a specific market and fulfilled the desire of Grand Tourists for sophisticated souvenirs of their travels.

His engravings, particularly "The Life of Masaccio," mark him as a figure of considerable importance in the history of art scholarship and taste. By making these relatively neglected masterpieces accessible, he contributed to a fundamental shift in the appreciation of early Renaissance art. This aspect of his work aligns him with other 18th-century antiquarians and scholars who were beginning to explore and document earlier periods of art and culture with new rigor.

While he may have been considered a somewhat marginal or eccentric figure by some of his more mainstream contemporaries in London, like Sir Joshua Reynolds (despite their interaction), his long and productive career in Italy, his connections with influential patrons like Sir Horace Mann, and the enduring interest in his varied body of work secure him a lasting place in the history of British and Italian art of the 18th century.

Conclusion

Thomas Patch was an artist of considerable talent, versatility, and character. His life as an expatriate in Italy placed him at the heart of the Grand Tour, a phenomenon he both served and satirized. His caricatures remain a delightful and insightful record of this era, while his Florentine views capture the enduring beauty of the city. Beyond these accomplishments, his pioneering engravings of early Renaissance masterpieces like those by Masaccio and Giotto demonstrate a scholarly commitment that had a lasting impact on the study and appreciation of art history. Though perhaps not always conforming to the artistic or social norms of his time, Thomas Patch left behind a body of work that continues to engage, amuse, and inform, securing his position as a noteworthy, if delightfully unconventional, figure in 18th-century European art.