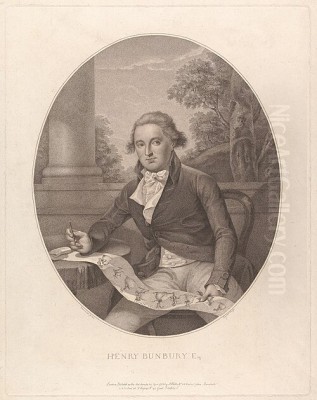

Henry William Bunbury (1750-1811) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the golden age of English caricature. An accomplished amateur artist hailing from the gentry, Bunbury carved a unique niche for himself with a style characterized by gentle humour, elegant lines, and a keen observation of social manners, contrasting with the more biting political satire of some of his contemporaries. His prolific output, ranging from social satires and sporting scenes to literary illustrations, offers a delightful window into the life and customs of late Georgian England. This exploration delves into his life, artistic development, key works, and his place within the vibrant artistic landscape of his time.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born in Mildenhall, Suffolk, in July 1750, Henry William Bunbury was the second son of Sir William Bunbury, the 5th Baronet, and Eleanor Graham. His upbringing within a landed gentry family provided him with a comfortable social standing and access to a classical education. He attended the prestigious Westminster School in London, a common training ground for the English elite, where his natural talent for drawing, particularly for humorous subjects, began to manifest.

Following Westminster, Bunbury matriculated at St Catharine's College, Cambridge. While his academic pursuits are not extensively detailed, it is clear that his passion for art continued to flourish during these years. Cambridge, like Oxford, was not a formal art academy, but it provided an environment where a young man of his station could cultivate his interests. It is likely that during his university years and through his social connections, he was exposed to a wide range of artistic influences, including the works of earlier English satirists and contemporary European prints. His early drawings from this period already hinted at the wit and observational skill that would define his later career. Unlike artists who underwent rigorous academic training under a specific master, Bunbury's development appears more self-directed, honed by personal practice and an innate ability to capture character and situation with a few deft strokes.

The Grand Tour and Artistic Development

Like many young gentlemen of his era, Bunbury embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe, a journey considered essential for completing one's education and cultural refinement. His travels, undertaken in the late 1760s, took him through France and Italy, exposing him to the masterpieces of classical and Renaissance art, as well as the diverse cultures and social scenes of the continent. While the direct influence of High Renaissance art on his caricatural style might seem limited, the experience undoubtedly broadened his visual vocabulary and sharpened his observational skills.

The social interactions, the different customs, the landscapes, and even the absurdities encountered during his travels likely provided rich material for his sketchbook. Caricature, with its roots in Italian art (from `caricare`, to load or exaggerate), was a genre he would have encountered directly. Artists like Pier Leone Ghezzi had long been popular in Rome for their witty exaggerations of locals and tourists alike. Bunbury’s own developing style, which focused on the humorous aspects of human behaviour and appearance, would have found resonance in this tradition. Upon his return to England, he brought with him not only a portfolio of sketches but also a more cosmopolitan perspective that informed his art.

A Gentleman Artist: Style and Approach

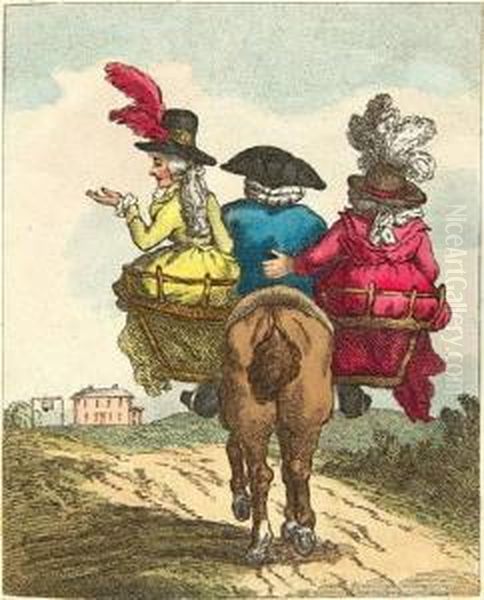

Bunbury’s artistic style is often described as amiable, graceful, and gently humorous. He was not a political firebrand like James Gillray, nor did he possess the boisterous, often coarse, energy of Thomas Rowlandson. Instead, Bunbury’s satire was typically social, targeting the foibles, fashions, and affectations of the society he knew well. His line is often fluid and elegant, and his compositions, even in their most comical moments, rarely descend into vulgarity. This refined approach made his work highly popular among a broad audience, including the very classes he often depicted.

Horace Walpole, the influential writer and connoisseur, famously dubbed Bunbury "the second Hogarth." While a flattering comparison, it requires qualification. William Hogarth, a towering figure from the preceding generation, used his "modern moral subjects" to deliver powerful, often didactic, social critiques. Bunbury, while an admirer of Hogarth, generally eschewed such overt moralizing. His aim was more to amuse than to reform, to highlight the comical rather than the corrupt. His subjects were often drawn from the everyday life of the gentry and the burgeoning middle class: scenes of domestic life, social gatherings, sporting pursuits, and the misadventures of travel. His characters, though exaggerated, often possess a charm and relatability that distinguishes his work. He was an amateur in the 18th-century sense of the word – a gentleman who pursued art for pleasure and passion rather than as a primary profession, though his output was prolific and widely disseminated through prints.

Key Themes in Bunbury's Oeuvre

Bunbury's artistic interests were diverse, reflecting his life experiences and the popular tastes of his time. Several recurring themes dominate his extensive body of work.

Social Satire and Manners: This is perhaps the area where Bunbury excelled most. He had a sharp eye for the absurdities of fashion, the pretensions of social climbers, and the humorous interactions of everyday life. Works like A Chop-House or The City Hunt capture the bustling, often chaotic, energy of urban and suburban life. He gently poked fun at the affectations of the beau monde, the awkwardness of social encounters, and the universal human experiences of embarrassment or minor misfortune. His depictions of crowded assemblies, tea parties, and public entertainments are filled with recognizable social types, each rendered with a characteristic quirk or expression.

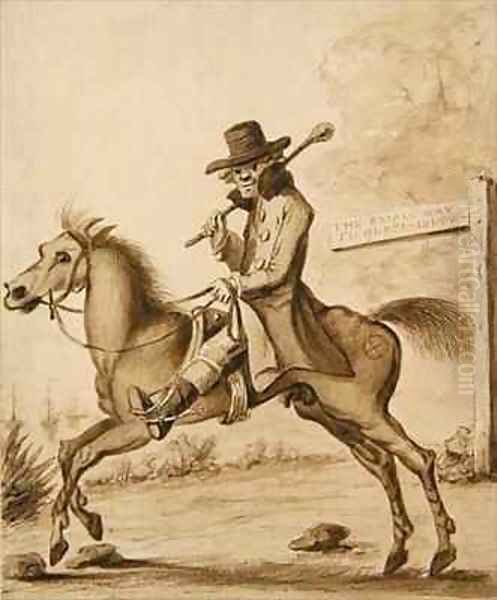

Horsemanship and Sporting Life: Bunbury was an enthusiastic horseman, and this passion is vividly reflected in his art. He produced numerous prints depicting various aspects of equestrian life, often with a humorous twist. His most famous series in this vein is An Academy for Grown Horsemen (1787), ostensibly by "Geoffrey Gambado, Esq.," a fictional riding master whose advice and demonstrations are hilariously inept. This was followed by Annals of Horsemanship (1791). These works satirize the pretensions of riding schools and the often-comical struggles of inexperienced riders, showcasing Bunbury's deep knowledge of horses and his ability to capture their movement and character, as well as the follies of their human companions. Fox hunting, racing, and other country sports also provided him with ample material.

Military Life: Having served as a captain and later Colonel in the West Suffolk Militia, Bunbury had firsthand experience of military life, particularly the less glamorous aspects of the militia and home guard. He produced several caricatures on military themes, often focusing on the amateurishness of volunteer soldiers, the discomforts of camp life, or the pomposity of officers. These works, while humorous, also offer a glimpse into the citizen-soldier experience during a period of frequent European conflicts.

Literary and Theatrical Illustration: Bunbury also turned his hand to illustrating literary works. He provided designs for editions of Shakespeare, most notably for Thomas Macklin's lavish "Poets' Gallery" project in the 1790s, for which he created a series of twenty-two watercolors. While these were more serious in intent than his caricatures, they still often retained a sense of character and narrative dynamism. He also illustrated works by his friend Oliver Goldsmith, including a humorous frontispiece for The Haunch of Venison. His interest in the theatre is evident in depictions of actors and theatrical scenes, reflecting the vibrant theatre culture of 18th-century London.

Masterpieces and Notable Works

While Bunbury produced a vast number of individual prints and series, several stand out for their popularity and representative quality.

A Country Club (1788): This is one of Bunbury's most celebrated social satires. It depicts a raucous gathering in a rural club, with members engaged in various states of inebriation, argument, and boisterous camaraderie. The composition is filled with lively details and individual character studies, capturing the uninhibited atmosphere of such an establishment. It showcases Bunbury's skill in orchestrating a complex scene with multiple figures, each contributing to the overall comedic effect.

A Long Minuet as Danced at Bath (1787): This innovative work is essentially a strip cartoon, a long, continuous frieze depicting a series of couples dancing the minuet at the fashionable spa town of Bath. Each couple is humorously characterized, from the elegant to the awkward, the youthful to the aged. The extended format allowed Bunbury to create a flowing narrative of social interaction and display, and it was immensely popular, being published in various formats. It highlights the importance of dance and social ritual in Georgian society and Bunbury's ability to capture movement and social nuance.

The Barber's Shop (published in various forms, e.g., 1803, 1811): This scene of a bustling barber's shop is another fine example of Bunbury's observational humor. It captures the various activities and characters one might find in such an establishment – a customer being shaved precariously, another enduring a painful wig fitting, all amidst the tools and clutter of the trade. It’s a snapshot of everyday urban life, rendered with wit and an eye for comical detail.

A Visit to the Camp: This print, and others like it, reflects his military interests. It often humorously depicts civilians, particularly fashionable ladies, visiting a military encampment, highlighting the contrast between refined society and the rougher realities of army life, or the awkward attempts of civilian men to appear martial.

Shakespeare Illustrations for Macklin's Poets' Gallery: Beginning in the late 1780s and exhibited in the 1790s, Thomas Macklin, a prominent publisher, commissioned leading artists of the day, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, Henry Fuseli, and Angelica Kauffman, to produce paintings of scenes from Shakespeare and other British poets, which were then engraved. Bunbury contributed a significant number of designs for the Shakespearean scenes. While perhaps not as dramatic or sublime as those by Fuseli, Bunbury's interpretations were praised for their characterization and narrative clarity. Works like his depiction of Falstaff or scenes from A Midsummer Night's Dream were popular.

A Chop House (1781): This print captures the lively, somewhat chaotic atmosphere of a typical London chophouse, a popular dining spot. Diners are shown eagerly consuming their meals, waiters rush about, and various social types are juxtaposed, creating a humorous tableau of public dining in the era.

These works, and many others, were widely disseminated as etchings and stipple engravings, often hand-coloured, making them accessible to a broad public. Their popularity attests to Bunbury's ability to connect with the tastes and sensibilities of his time.

Bunbury in the Context of 18th-Century British Caricature

The latter half of the 18th century was a golden age for British caricature. Freedom of the press, a politically engaged public, and a thriving print market created fertile ground for satirical artists. Bunbury operated within this vibrant ecosystem, which included several other notable figures.

William Hogarth (1697-1764) was the undisputed father of English satirical art. His engraved series like A Rake's Progress and Marriage A-la-Mode set a high bar for narrative and social critique. While Bunbury was called "the second Hogarth," his aims and methods differed, being generally less concerned with profound moral lessons.

Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) was a contemporary known for his robust, often bawdy, and incredibly energetic style. Rowlandson's caricatures, like his famous Dr. Syntax series, were full of life and movement, and he did not shy away from the grotesque or the risqué. His social satire was often broader and more boisterous than Bunbury's more refined humour.

James Gillray (1756-1815) was the master of political caricature. His prints were savage, inventive, and deeply influential, lampooning leading political figures like William Pitt, Charles James Fox, and Napoleon with unparalleled ferocity and graphic power. Bunbury largely avoided the direct political commentary that was Gillray's forte, preferring to focus on social manners.

Isaac Cruikshank (1764-1811), father of the even more famous George Cruikshank, was another prolific caricaturist of the period, producing a wide range of social and political satires. His style was robust and direct, often catering to popular sentiment.

Other artists like Paul Sandby (1731-1809), known primarily as a topographical watercolourist, also produced early caricatures. Printmakers and publishers such as Matthew Darly and Mary Darly were instrumental in popularizing caricature. Bunbury’s work stands apart from these through its characteristic gentility. He was less of a political combatant than Gillray, less Rabelaisian than Rowlandson, and less overtly moralizing than Hogarth. His niche was the comedy of manners, observed with an insider's eye and rendered with an elegance that appealed to a polite society that enjoyed laughing at itself, provided the laughter was not too harsh.

Social Standing, Connections, and Collaborations

Bunbury's position as a member of the gentry afforded him social access and connections that were beneficial to his artistic pursuits, though he was not dependent on art for his livelihood. In 1787, he was appointed Equerry to Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, the second son of King George III. This royal appointment brought him into court circles and further solidified his social standing. He was a popular figure, known for his wit and amiable personality.

His circle of friends included some of the leading cultural figures of the day. He was well-acquainted with Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), the first President of the Royal Academy and the preeminent portrait painter of the era. He was also a friend of the celebrated writer Oliver Goldsmith (c.1728-1774), for whose poem The Haunch of Venison he provided an illustration, and the legendary actor-manager David Garrick (1717-1779). These connections placed him at the heart of London's artistic and literary life. Other prominent figures in the art world he would have known included portraitists like Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) and George Romney (1734-1802), and historical painters like Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) and Benjamin West (1738-1820), who succeeded Reynolds as President of the Royal Academy.

Bunbury himself was primarily a draughtsman. His original works were typically pen and ink drawings, often enhanced with watercolour washes. For these to reach a wider public, they needed to be translated into prints. He collaborated with several skilled engravers who could faithfully reproduce his style. James Bretherton the elder (fl. c. 1770–1790) was one of his earliest and most frequent engravers. Other notable engravers who worked on his designs included William Dickinson (1746-1823), known for his fine mezzotints, Thomas Watson (1750-1781), and the celebrated Italian engraver Francesco Bartolozzi (1727-1815), who was renowned for his stipple engravings and elegant style, well-suited to some of Bunbury's more sentimental or graceful compositions. John Raphael Smith (1751-1812), another master of mezzotint, also engraved Bunbury's work. Publishers like Thomas Macklin, the Bowles family (Carrington Bowles and later Bowles & Carver), and S.W. Fores were crucial in commissioning, printing, and distributing his caricatures.

Techniques and Artistic Output

Bunbury's primary medium for his original designs was drawing, utilizing pen and ink, often combined with grey or coloured washes (watercolour) to add depth and vibrancy. His line was typically fluid and expressive, capable of capturing character and movement with apparent ease. He was not a painter in oils in any significant capacity, nor was he, generally, his own engraver. His strength lay in the conception and execution of the initial design.

The process usually involved Bunbury creating a detailed drawing. This drawing would then be handed over to a professional engraver. Etching was a common method, where the design was incised onto a copper plate, which could then be inked and printed. Stipple engraving, popularized by Bartolozzi, used dots rather than lines to create tonal effects and was often favoured for more delicate subjects. Mezzotint, another popular technique, excelled at producing rich, velvety tones. Once printed, many of these engravings were then hand-coloured, often by teams of women and children working for the print-sellers, adding to their visual appeal and commercial value.

His output was considerable. Hundreds of individual prints after his designs were published during his lifetime, covering a wide array of subjects. These were sold in the bustling print shops of London, which were popular places of resort, their windows filled with the latest satirical images. His works were also sometimes bound into collections or published as series, like the Gambado books on horsemanship.

Personal Life and Final Years

In 1771, Henry William Bunbury married Catherine Horneck (c. 1754–1799), daughter of Captain Kane William Horneck and Hannah Triggs. Catherine and her sister Mary were celebrated beauties and part of Oliver Goldsmith's circle; Goldsmith affectionately nicknamed Catherine "Little Comedy." The marriage appears to have been a happy one, and they had two sons: Charles John Bunbury (1772–1798) and Henry Edward Bunbury (1778–1860). The latter, Sir Henry Edward Bunbury, 7th Baronet, went on to have a distinguished military and political career and was also a historical writer.

Despite his artistic activities and social engagements, Bunbury also maintained his military commitments, serving as Colonel of the West Suffolk Militia. He divided his time between London, his family estates in Suffolk, and his military duties. His wife Catherine predeceased him in 1799.

Henry William Bunbury died on May 7, 1811, in Keswick, Cumberland (now Cumbria), in the Lake District, at the age of 60 or 61. He was buried there, far from his Suffolk origins but in a region whose picturesque beauty was increasingly appreciated by artists and writers of the Romantic era, such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Legacy and Lasting Appeal

Henry William Bunbury's legacy is that of a gifted and amiable satirist who captured the spirit of his age with wit and elegance. While he may not have possessed the political incisiveness of Gillray or the raw energy of Rowlandson, his contribution to the art of caricature is undeniable. He excelled in depicting the comedy of manners, the absurdities of social life, and the humorous side of human nature. His works were immensely popular in his lifetime, offering amusement and a gentle critique of contemporary society.

His influence can be seen in the development of social caricature and comic illustration in the 19th century. Artists like George Cruikshank (1792-1878), while often more biting, inherited the tradition of detailed social observation. Bunbury's narrative sequences, like A Long Minuet, also prefigure later developments in comic strip art.

Today, Bunbury's prints are valuable historical documents, providing rich visual information about the customs, fashions, and social interactions of Georgian England. They are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the British Museum in London and the Lewis Walpole Library at Yale University. For art historians and enthusiasts of the period, his work remains a source of delight and insight, a testament to an artist who, with a light touch and a keen eye, chronicled the world around him with enduring charm and humour. He remains a key figure for understanding the breadth and diversity of one of the most vibrant periods in British graphic art.