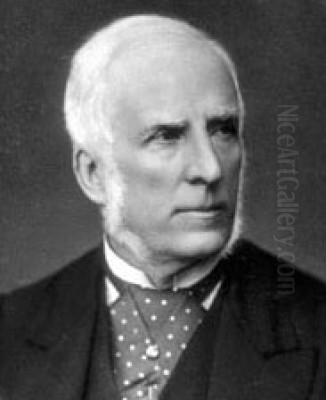

John Callcott Horsley RA (29 January 1817 – 18 October 1903) stands as a significant, if sometimes controversial, figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. A prolific narrative painter, a staunch member of the Royal Academy, and an artist deeply embedded in the Victorian era's social and moral fabric, Horsley's career spanned a period of immense change in artistic tastes and practices. While he is widely remembered today for a singular, almost accidental, innovation – the design of the first commercial Christmas card – his broader artistic output and his role within the art establishment of his time offer a fascinating window into Victorian culture.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in London, John Callcott Horsley was fortunate to be immersed in a highly cultured and artistic environment from his earliest years. His father was William Horsley, a respected musician and composer, and his mother, Elizabeth Hutchins Callcott, was the sister of Sir Augustus Wall Callcott, a distinguished landscape painter and a Royal Academician. This familial connection to the arts, particularly through his esteemed uncle, undoubtedly played a pivotal role in shaping young John's aspirations. Sir Augustus Wall Callcott, known for his serene landscapes and marine paintings, provided not only inspiration but likely practical guidance and encouragement.

It was under his great-uncle's influence that Horsley decided to pursue art formally. In 1831, at the age of fourteen, he enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Here, he would have received a traditional academic art education, focusing on drawing from casts of classical sculptures, life drawing (though his later views on this would become notable), and the study of Old Masters. The curriculum was designed to instill a strong foundation in draughtsmanship, composition, and the historical hierarchy of genres, with historical and religious painting at its apex.

During these formative years, Horsley developed a particular admiration for the Dutch Golden Age masters of the 17th century. Artists such as Pieter de Hooch, renowned for his tranquil domestic interior scenes, and Johannes Vermeer, with his masterful use of light and intimate portrayals of daily life, left a discernible mark on Horsley's developing style. The meticulous detail, the careful rendering of textures, and the quiet dignity of ordinary moments found in Dutch genre painting resonated with Horsley and would inform his approach to narrative and subject matter throughout his career, even as he tackled grander historical themes. Other Dutch artists like Gabriel Metsu and Gerard ter Borch, with their refined depictions of bourgeois life, also likely contributed to this early influence.

The Genesis of the Christmas Card: An Enduring Legacy

Perhaps Horsley's most widely recognized, yet somewhat incidental, contribution to popular culture is his design of the first commercially produced Christmas card. This came about in 1843 at the behest of his friend, Sir Henry Cole. Cole, later the first director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, was a prominent civil servant, inventor, and a key figure in 19th-century design reform. He was looking for a convenient way to send seasonal greetings to his many acquaintances without the laborious task of writing individual letters, a common practice during the busy Christmas period.

Horsley was commissioned to create a design that could be lithographed and hand-coloured. The resulting card featured a triptych layout. The central panel depicted a multi-generational family enjoying a festive gathering, raising their glasses in a toast. Flanking this scene were smaller panels illustrating acts of charity: feeding the hungry on one side and clothing the naked on the other. The message printed beneath read, "A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You."

Approximately one thousand copies of this card were printed and sold for one shilling each – a not insignificant sum at the time. While the concept was innovative, the card was not without its detractors. The central image of a family, including young children, partaking in wine, drew criticism from the burgeoning temperance movement, which viewed it as promoting alcohol consumption. Despite this initial controversy, the idea of sending pre-printed Christmas greetings quickly caught on. Horsley's design, though perhaps not an artistic masterpiece in his own estimation, inadvertently launched a tradition that would grow into a global industry, forever associating his name with this festive custom. The card's emphasis on family, celebration, and charitable giving perfectly encapsulated Victorian Christmas ideals, which were themselves being popularized by writers like Charles Dickens around the same period.

Narrative Painting and Historical Subjects

Beyond the Christmas card, Horsley was primarily a narrative painter, specializing in historical, literary, and domestic genre scenes. His early career saw him achieve success with works that drew upon historical and literary sources. In 1843, the same year as the Christmas card, his cartoon (a full-scale preparatory drawing) titled St. Augustine Preaching to Ethelbert and Bertha, Christian Inhabitants of Britain won a prize in the competition for frescoes to decorate the new Houses of Parliament. This success led to commissions for actual frescoes in the Palace of Westminster, including Religion (1845) in the House of Lords and later Satan Touched by Ithuriel's Spear while Whispering Evil Dreams to Eve and Henry V, when Prince of Wales, Believing the King Dead, Takes the Crown from the Pillow. These monumental works placed him alongside other prominent artists involved in the Parliament decoration scheme, such as Daniel Maclise, Charles West Cope, and William Dyce.

Horsley's paintings often displayed a strong narrative clarity, careful composition, and a rich, somewhat subdued palette. He frequently drew inspiration from literature, with works like L'Allegro and Il Penseroso (inspired by John Milton's poems) and Malvolio from Twelfth Night. His historical scenes were meticulously researched, reflecting the Victorian era's fascination with the past. Titles such as The Death Chamber, A Scene from Don Quixote, and Lady Jane Grey and Roger Ascham indicate the range of his subject matter. He was adept at capturing dramatic moments and conveying emotion, though always within the bounds of Victorian propriety. His style, while influenced by the Dutch, also showed an affinity with the detailed realism and narrative focus of contemporaries like William Powell Frith, known for his panoramic scenes of modern life such as Derby Day, and Augustus Egg, whose moralizing triptych Past and Present explored contemporary social issues.

The Cranbrook Colony: Idyllic Ruralism

In the 1850s, Horsley's focus began to shift somewhat towards more contemporary themes, particularly scenes of rural life. This interest led to his association with a group of artists known as the Cranbrook Colony. Horsley had purchased a house and studio, Willesley, in Cranbrook, Kent, a picturesque rural area. He was soon joined by other artists who were drawn to the charm of the countryside and the perceived innocence and simplicity of its inhabitants.

Key figures in the Cranbrook Colony, alongside Horsley, included Thomas Webster, Frederick Daniel Hardy, and George Bernard O'Neill. While not a formal "school" with a defined manifesto, these artists shared a common interest in depicting sentimental and often idealized scenes of village life: children at play, cottage interiors, local tradespeople, and festive gatherings. Their work was characterized by careful observation, a high degree of finish, and a gentle, often humorous, narrative. George Hardy, brother of Frederick Daniel Hardy, also became part of this artistic circle.

The Cranbrook artists often used local villagers as models and depicted recognizable local settings. Horsley's contributions to this genre included paintings like Showing a Preference and The Stolen Kiss. These works found a ready market among the increasingly affluent middle class, who appreciated their charm, their perceived moral wholesomeness, and their nostalgic evocation of a vanishing rural England in an era of rapid industrialization. The Colony's output can be seen as part of a broader Victorian trend for genre painting, which included artists like Luke Fildes (in his earlier, less socially critical phase) and Frank Holl, though the Cranbrook artists generally avoided the more overtly social realist themes tackled by some of their contemporaries.

A Moral Stance: The "Clothes-Horsley" Controversy

One of the most defining, and controversial, aspects of John Callcott Horsley's later career was his outspoken opposition to the use of nude models in art education and exhibition. This stance became particularly prominent during his tenure as Rector (often referred to as Treasurer in some sources, a key administrative role) of the Royal Academy from 1875 to 1897 (or near his death, sources vary slightly on the end date of his active role).

Horsley believed that the study of the nude, particularly the female nude, was morally corrupting for artists and unnecessary for the creation of great art. He argued that it could even detract from an artist's understanding of structure and movement, a somewhat idiosyncratic view. This position put him at odds with many of his contemporaries and with the long-standing academic tradition that saw life drawing as fundamental to artistic training. His campaign against the nude in the 1880s, which included writing letters to The Times, earned him the derisive nickname "Clothes-Horsley" from students and sections of the art press.

This moral crusade reflected a broader Victorian anxiety about sexuality and public decency, but in the art world, it was seen by many as reactionary and philistine. Artists like Sir Frederic Leighton, President of the Royal Academy for much of this period, and Edward Poynter, both of whom frequently depicted the nude in their classical and mythological subjects, represented a more liberal academic viewpoint. The emerging Aesthetic Movement, with artists like Albert Moore and James McNeill Whistler, also championed "art for art's sake," often challenging Victorian moral conventions, further highlighting the generational and ideological divide. Horsley's stance, however, was not entirely isolated; it found sympathy among more conservative elements of society and the art world who shared his concerns about the perceived decline in public morality.

Horsley and the Royal Academy: An Establishment Figure

John Callcott Horsley was deeply involved with the Royal Academy throughout his career. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1855 and became a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1864. His long service as Rector/Treasurer from the mid-1870s placed him in a significant administrative and influential position within this powerful institution.

During his time in office, the Royal Academy faced increasing challenges to its authority and artistic dominance. New artistic movements, such as Impressionism, which was gaining traction in France with artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro and beginning to influence British painters like Philip Wilson Steer, were largely met with suspicion and resistance by the Academy's old guard, including Horsley. He was known for his conservative views on art, championing traditional techniques and subject matter and opposing what he saw as the radical and often incomprehensible trends of modern art.

His opposition to the nude was part of this broader conservatism. He sought to maintain the Royal Academy as a bastion of traditional artistic values and moral propriety. While this made him a figure of ridicule for some, it also solidified his position as a defender of established norms for others. His influence within the Academy was considerable, and he played a role in shaping its exhibitions and policies during a critical period of transition in the British art world. His relationship with other Academicians would have been complex; while sharing a common institutional loyalty with figures like Sir Edwin Landseer (who died just as Horsley's rectorship began) or William Powell Frith, his specific moral crusades likely created friction even among fellow traditionalists.

Anecdotes and Character: Glimpses of the Man

Beyond his public pronouncements and artistic output, a few anecdotes offer glimpses into Horsley's character. One particularly poignant story reveals a compassionate side often overshadowed by his stern public persona. It is recorded that Horsley would voluntarily visit public morgues to sketch the faces of recently deceased children whose bodies were unclaimed or unidentified. He did this, he reportedly said, because "if I did not, I should not fulfil my mission." This act suggests a deep-seated empathy and a sense of social responsibility, using his artistic skill for a purpose far removed from fame or financial gain. It speaks to a Victorian sensibility that combined artistic practice with a sense of duty and moral purpose.

His family life was also central to him. He was married twice, first to Elvira Walter, and after her death, to Rosamund Haden, sister of the prominent surgeon and etcher Sir Francis Seymour Haden. He had several children, some of whom also pursued artistic careers, continuing the family tradition. His son, Sir Victor Horsley, became a renowned surgeon and scientist. This familial context, rooted in artistic and intellectual pursuits, underscores the environment that shaped him.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

John Callcott Horsley continued to paint and exhibit at the Royal Academy well into his later years. His style remained largely consistent, rooted in the narrative and technical traditions he had embraced throughout his career. While artistic tastes were shifting dramatically around him with the rise of Post-Impressionism and early modernism, Horsley remained a steadfast representative of Victorian academic painting.

He died on 18 October 1903 in Kensington, London, at the age of 86. By the time of his death, the art world was a very different place from the one he had entered as a young student. His brand of narrative painting, once highly popular, had fallen out of critical favor, often dismissed as sentimental or overly literary by proponents of more avant-garde approaches.

Today, John Callcott Horsley is remembered for several distinct, though interconnected, reasons. Firstly, and most popularly, as the designer of the first Christmas card, an innovation that has had a lasting global impact on social customs. Secondly, as a competent and prolific Victorian narrative painter whose works provide valuable insights into the tastes, values, and preoccupations of his era. His historical scenes, literary interpretations, and depictions of rural life are part of the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art. Thirdly, he is remembered for his staunch, if controversial, moral conservatism, particularly his campaign against the nude in art, which made him a notable figure in the cultural debates of his time.

His paintings are held in various public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate Britain, and regional galleries throughout the United Kingdom. While he may not be ranked among the most revolutionary or groundbreaking artists of the Victorian era, like J.M.W. Turner (who was an elder statesman of the RA when Horsley was young) or the Pre-Raphaelites such as John Everett Millais or Dante Gabriel Rossetti (whose early rebellion transformed into later establishment success for Millais), Horsley's career offers a compelling case study of an artist who successfully navigated the Victorian art world, achieved considerable recognition, and left an indelible, if somewhat unexpected, mark on popular culture. His life and work reflect the complexities, contradictions, and enduring traditions of art in 19th-century Britain.