Traugott Hermann Rüdisühli stands as a notable figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. A Swiss national, born in Lenzburg, Canton Aargau, in 1864, his life and career unfolded across Switzerland and Germany, leaving a mark both as a painter steeped in the Symbolist tradition and as a dedicated art educator. His artistic journey was significantly shaped by his family background, his formal training, and his engagement with the prevailing artistic currents of his time, particularly the powerful influence of Arnold Böcklin. Though perhaps not as widely celebrated today as some of his contemporaries, Rüdisühli's work and educational contributions offer valuable insights into the artistic milieu of the era. His story is one of dedicated practice, academic leadership, and ultimately, resilience in the face of personal hardship during tumultuous times. He passed away in Munich in 1944, leaving behind a legacy tied to the atmospheric and often melancholic beauty of Symbolist painting.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

The foundations of Traugott Hermann Rüdisühli's artistic path were laid early in life, nurtured within an environment where art was clearly valued. His initial training began under the guidance of his own father, Jacob Lorenz Rüdisühli, himself an artist. This familial introduction to the principles and practices of art provided a crucial starting point before he pursued more formal education. This kind of apprenticeship, whether formal or informal, within an artistic family was not uncommon during the period and often provided a strong technical grounding.

Seeking to build upon this foundation, Rüdisühli enrolled at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) in Basel. These institutions played a vital role in design and applied arts education across German-speaking Europe, often providing a more practical counterpoint to the fine art focus of the academies. His time in Basel would have exposed him to rigorous training in drawing, design principles, and potentially various craft techniques, further honing his skills.

His ambition, however, clearly extended towards the realm of fine art painting. Between 1883 and 1887, Rüdisühli undertook advanced studies at the prestigious Kunstakademie (Art Academy) in Karlsruhe, Germany. This move marked a significant step, placing him within one of the important centers for academic art training in the region. Studying at an academy like Karlsruhe meant immersion in a structured curriculum emphasizing life drawing, composition, and the study of Old Masters, considered essential for aspiring painters.

During his time in Karlsruhe, Rüdisühli had the opportunity to learn from notable figures. His teachers included Ferdinand Keller, a respected history and portrait painter associated with the academy for many years, and Karl Brünner. Studying under established artists like Keller would have provided Rüdisühli with direct exposure to the academic standards and techniques favored at the time, likely focusing on realism, historical subjects, and portraiture, even as new artistic movements began to challenge these conventions elsewhere. This academic grounding would form the bedrock upon which his later, more Symbolist-influenced style would develop.

Leadership in Art Education

Following his formative years of study, Traugott Hermann Rüdisühli transitioned into a role that highlighted his capabilities not only as an artist but also as an administrator and educator. For a significant period, spanning from 1888 to 1898, he took on leadership positions within the art education system. He served as the director or principal (the sources use terms like "Leiter" which can mean head or director) of art schools in both Stuttgart, Germany, and Basel, Switzerland. This decade of educational leadership represents a distinct and important phase in his professional life.

Holding such positions required a blend of artistic knowledge, pedagogical insight, and administrative skill. As director, Rüdisühli would have been responsible for overseeing the curriculum, managing faculty, guiding students, and likely liaising with local authorities or governing bodies. His own training at both a Kunstgewerbeschule and a Kunstakademie would have given him a broad perspective on the different facets of art education, from applied crafts to fine arts.

The late 19th century was a period of significant development and debate regarding art education. The traditional academy system was being challenged by new approaches, and the role of Kunstgewerbeschulen was evolving alongside industrialization and changing design needs. Rüdisühli's leadership during this decade placed him directly within these developments. His work in Stuttgart and Basel contributed to the training of a new generation of artists and craftspeople, shaping the artistic landscape of these cities.

This period of intense involvement in education likely influenced his own artistic practice as well, demanding a constant engagement with artistic principles and the challenges of teaching them. It also suggests a commitment to fostering artistic talent beyond his personal creative output. While specific details of his pedagogical approach or reforms he might have implemented are scarce in the available summaries, his decade-long tenure in these demanding roles underscores his standing and capability within the educational sphere of the art world at that time.

The Munich Period and Symbolist Affinities

After his dedicated service in art education, Traugott Hermann Rüdisühli sought further artistic development and relocated to Munich. This move around the turn of the century placed him in one of the most dynamic and important art centers in Europe. Munich was a magnet for artists from across Germany and beyond, known for its prestigious academy, its vibrant gallery scene, and the influential Munich Secession movement, which had formed in 1892 as a progressive alternative to the established art institutions.

It was during his time in Munich that the influence of the Swiss-German Symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901) became particularly pronounced in Rüdisühli's work. Böcklin, although he died shortly after the turn of the century, cast a long shadow over the Munich art scene and Symbolism in general. His atmospheric landscapes, often populated with mythological figures and imbued with a sense of mystery, melancholy, or drama, resonated deeply with many artists seeking alternatives to Naturalism and Impressionism.

Rüdisühli's adoption of a style influenced by Böcklin suggests an alignment with the broader Symbolist movement. Symbolism prioritized subjective experience, emotion, ideas, and the mystical over objective reality. Artists like Böcklin, and by extension Rüdisühli, used landscape, mythology, and allegory to explore psychological states and deeper meanings. This often involved rich, sometimes somber color palettes, dramatic lighting, and a focus on mood and atmosphere. Munich itself was a fertile ground for Symbolism, with artists like Franz Stuck also exploring mythological themes with a distinctive, often darker, sensuousness.

While living and working in Munich, Rüdisühli gained a notable reputation within the city's art circles. The available information mentions connections with prominent art patrons, although specific names are not provided. Such connections were crucial for artists, providing financial support, commissions, and access to influential networks. His presence in Munich placed him amidst contemporaries like Lovis Corinth and near the legacy of figures like Hans Thoma, who also spent significant time there. Rüdisühli's engagement with the Munich art world, particularly his affinity for Böcklin's Symbolist vision, defined his mature artistic identity.

Representative Works and Style

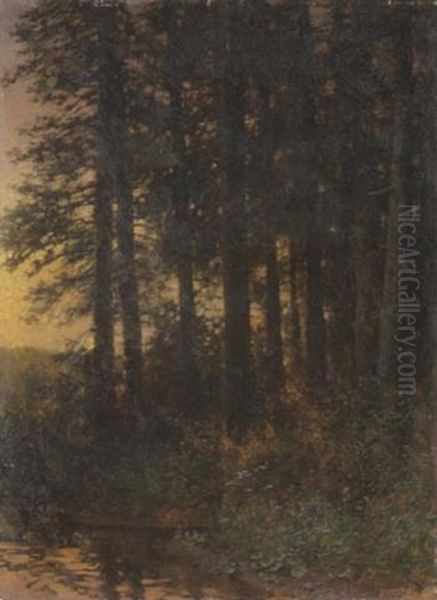

While comprehensive catalogues of Traugott Hermann Rüdisühli's oeuvre might be scarce, known examples and descriptions of his work align closely with the expected style of an artist influenced by Arnold Böcklin and working within the Symbolist tradition. His paintings often focused on landscapes, frequently imbued with a specific mood or atmosphere, suggesting a deeper emotional or symbolic content beyond mere representation. Titles like "Waldinneres" (Forest Interior) or "Abendstimmung am See" (Evening Mood by the Lake) point towards this focus on nature infused with feeling.

These landscapes were likely rendered with attention to detail but also with a sensitivity to light and color designed to evoke particular emotions – perhaps the quiet melancholy of twilight, the mysterious depths of a forest, or the tranquil expanse of water under specific atmospheric conditions. This approach echoes Böcklin's famous works, such as the various versions of "Isle of the Dead," which use landscape elements – dark waters, towering cypresses, imposing architecture – to create a powerful sense of solemnity and mystery. Rüdisühli's forest scenes might similarly explore themes of solitude, nature's power, or the passage of time.

Beyond pure landscapes, Rüdisühli is also noted for exploring mythological or allegorical themes, another hallmark of Symbolism. Like Böcklin, Max Klinger in Germany, or Gustave Moreau in France, Symbolist painters often turned to ancient myths or created their own symbolic narratives to express complex ideas about life, death, love, and the human psyche. Rüdisühli's mythological works would likely feature figures integrated into evocative natural settings, drawing on classical or Germanic legends to convey deeper meanings. The style would probably emphasize mood and narrative suggestion over strict anatomical accuracy or historical detail.

His technique likely involved careful layering of paint to achieve depth and luminosity, using color not just descriptively but emotionally. The overall effect would be one of poetic realism, where the depicted scene feels tangible yet simultaneously points towards an unseen, symbolic dimension. His work can be situated within the broader context of late Romantic and Symbolist landscape painting, sharing affinities with artists like Giovanni Segantini in his Alpine scenes or perhaps the more northern, introspective moods found in some works by Edvard Munch, though likely without Munch's radical expressionistic distortion.

Artistic Context: Switzerland, Germany, and Symbolism

Traugott Hermann Rüdisühli's career unfolded across the interconnected art worlds of Switzerland and Germany during a period of significant artistic transition. Born Swiss, he received training in both countries and spent much of his mature career in Munich, a major German art hub. His work, therefore, reflects influences and trends present in both national contexts, unified by his strong connection to the international Symbolist movement.

In Switzerland, the late 19th century saw the towering figure of Ferdinand Hodler rise to prominence. Hodler developed his own distinct brand of Symbolism, characterized by strong lines, rhythmic compositions ("Parallelism"), and monumental figures often conveying national or universal themes. While both Rüdisühli and Hodler were Swiss Symbolists, Rüdisühli's style, influenced by the more painterly and atmospheric Böcklin (who, though often associated with Germany and Italy, was also Swiss-born), likely differed significantly from Hodler's linear and often starker approach. Other Swiss artists like Félix Vallotton were also active, though Vallotton moved more towards the Nabi group and later a cool realism.

In Germany, the art scene was diverse. Academic traditions remained strong in institutions like the Karlsruhe academy where Rüdisühli studied under Ferdinand Keller. However, challenges arose from various movements. Naturalism had its proponents, while Impressionism, championed by artists like Max Liebermann (a key figure in the Berlin Secession), offered a brighter, more modern sensibility focused on capturing fleeting moments of light and life. Symbolism, however, represented a significant counter-current, reacting against both academic historicism and what some saw as the superficiality of Impressionism.

Munich, where Rüdisühli settled, was a crucible for these competing trends. The Munich Secession, founded in 1892, included artists with diverse styles but shared a desire for greater artistic freedom and quality. Figures like Franz Stuck represented a powerful, sometimes decadent, form of Symbolism, while others like Lovis Corinth were moving towards a vigorous German Impressionism or Expressionism. Rüdisühli, with his Böcklin-influenced style, fitted comfortably within the Symbolist wing of the Munich art scene. His work contributed to the rich tapestry of styles exploring interior states, mythology, and atmospheric landscape that characterized this era, standing alongside German contemporaries like Max Klinger, known for his intricate graphic cycles and sculptures, and Hans Thoma, celebrated for his idyllic landscapes often tinged with allegory. The international nature of Symbolism also connected Rüdisühli's work conceptually to artists like Odilon Redon in France or even the early works of Edvard Munch in Norway.

Later Life and Legacy

The later years of Traugott Hermann Rüdisühli's life were marked by profound hardship, largely due to the devastating impact of World War II. Having established himself in Munich, a city that became a major target for Allied bombing raids, Rüdisühli experienced personal catastrophe. His house and studio were destroyed during an air raid, obliterating not only his home but likely a significant portion of his life's work – paintings, drawings, studies, and personal records. This loss, combined with the general privations of wartime Germany, plunged him into poverty during his final years.

This tragic end contrasts sharply with the earlier periods of his life, marked by successful studies, leadership roles in art education, and a respected position within the Munich art community, including connections to patrons. The destruction of his studio represents an irretrievable loss for the historical record, making a full assessment of his oeuvre potentially more difficult today. He passed away in Munich in 1944, amidst the final, brutal stages of the war, at the age of 80.

Despite the difficulties of his later life and the fact that his name may not resonate as strongly today as Böcklin, Hodler, or Stuck, Rüdisühli's legacy endures primarily through two avenues. Firstly, his contribution as an art educator during his decade leading schools in Stuttgart and Basel should not be underestimated. He played a direct role in shaping the skills and perspectives of numerous students, contributing to the continuity and development of artistic practice in the region. The influence of a dedicated teacher and administrator often extends subtly but significantly through the subsequent generations they mentored.

Secondly, his paintings, particularly those reflecting the Symbolist influence of Arnold Böcklin, remain as testaments to his artistic vision. Works held in collections, possibly including those mentioned in Zurich, Munich, and Mainz, or appearing on the art market, allow us to appreciate his skill in creating atmospheric landscapes and evocative scenes. He represents a specific current within Symbolism – one deeply tied to the German-speaking world and the particular moodiness of Böcklin's legacy. His work offers a valuable comparison point to other Symbolists and contributes to our understanding of the diverse artistic responses to modernity at the turn of the 20th century. He remains a figure worthy of study for his dedication to both creating and teaching art.

Conclusion

Traugott Hermann Rüdisühli (1864-1944) navigated the complex artistic landscape of the late 19th and early 20th centuries as both a dedicated painter and an influential educator. His journey began in Switzerland, rooted in family artistic tradition and formalized through studies in Basel and Karlsruhe under teachers like Ferdinand Keller. His subsequent leadership roles at art schools in Stuttgart and Basel demonstrated a commitment to fostering artistic talent that spanned a crucial decade.

His move to Munich marked a period of artistic maturity, where his work became deeply imbued with the spirit of Symbolism, heavily influenced by the atmospheric and mythological paintings of Arnold Böcklin. Rüdisühli carved out a niche for himself within the vibrant Munich art scene, creating evocative landscapes and thematic works that resonated with the Symbolist quest for deeper meaning and emotional expression, placing him in dialogue with contemporaries like Franz Stuck and the legacy of figures such as Hans Thoma. While perhaps overshadowed by more famous names like Ferdinand Hodler in Switzerland or Max Klinger in Germany, his work contributed to the rich diversity of Symbolist art.

Despite a later life tragically marred by the destruction of his home and studio during World War II and subsequent poverty, Rüdisühli's contributions persist. His legacy lies in his surviving paintings, which offer a window into a specific vein of Swiss-German Symbolism, and in his significant, though less tangible, impact as an art educator who helped shape a generation of artists. He remains a figure whose life and work reflect the artistic currents, educational structures, and historical turmoils of his time.