Robert Loftin Newman (1827-1912) stands as a unique and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. A painter of deeply personal and often melancholic vision, Newman eschewed the grand narratives and detailed realism favored by many of his contemporaries. Instead, he delved into a world of literary, biblical, and mythological themes, rendered in a distinctive style characterized by rich, jewel-like color, suggestive forms, and an intimate scale. Though not widely celebrated during his lifetime, his work has since garnered appreciation for its poetic intensity and its alignment with the more introspective currents of American Romanticism and Symbolism.

Early Life and Artistic Stirrings

Born in Richmond, Virginia, on November 10, 1827, Robert Loftin Newman was the son of Robert L. Newman and Sarah J. Matthews. His early life was marked by change; his father passed away when Robert was young, and after his mother remarried, the family relocated to Clarksville, Tennessee, around 1838. It was in Tennessee that Newman's artistic inclinations began to surface. He initially ventured into portraiture, a common starting point for aspiring artists seeking patronage. However, these early attempts were reportedly met with rejection from clients, a perhaps formative experience that may have steered him away from commissioned work later in his career.

A significant moment in his early artistic journey occurred in 1846 when he sought to become a pupil of Asher B. Durand, a leading figure of the Hudson River School, known for his meticulous landscapes and portraits. Durand, however, declined to take him on as a student. Undeterred, Newman continued to pursue his art. A breakthrough of sorts came in 1849 when his painting, "Music on a Shop-Board," was accepted by the American Art-Union. The sale of this work provided him with the means to travel to Europe, a crucial step for many ambitious American artists of the era seeking advanced training and exposure to the masterpieces of the Old World and contemporary European art.

Formative European Sojourns and Barbizon Influences

In 1850, Newman embarked on his first trip to Paris. This initial period of study lasted approximately five months. During this time, he is believed to have briefly studied with Thomas Couture, a prominent academic painter whose atelier attracted many international students, including a number of Americans like William Morris Hunt. Couture was known for his emphasis on sound draughtsmanship and rich painterly techniques, aspects that Newman would later internalize in his own unique way.

Newman returned to Europe in 1854, again drawn to Paris and its vibrant art scene. This second sojourn proved particularly influential. He deepened his engagement with contemporary French art, notably connecting with painters associated with the Barbizon School. It is documented that through William Morris Hunt, who had become a disciple of Jean-François Millet, Newman was introduced to Millet himself. The Barbizon painters, including Millet, Théodore Rousseau, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Charles-François Daubigny, had turned away from academic historical painting to depict rural life and landscape with a new sense of realism and poetic feeling. Their emphasis on mood, atmosphere, and often somber color palettes resonated with Newman's developing sensibilities. He also reportedly associated with other, perhaps less famous, French artists like a "William Morris Franklin" (though this name is not widely recognized and might be a confusion with Hunt or another figure) and "Michel Houel." The Barbizon influence, with its focus on suggestive rather than highly finished surfaces and its often intimate, emotional tone, would become a lasting element in Newman's artistic DNA.

Return to America, Civil War, and Early Career Struggles

After his European studies, Newman returned to the United States. Around 1858, he opened a studio in Clarksville, Tennessee, once again attempting to establish himself by accepting commissions for full-length and "crayon" (likely pastel or charcoal) portraits. However, the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 profoundly disrupted his artistic career, as it did for many artists in both the North and South.

Newman served the Confederacy, reportedly as an artillery lieutenant. His military service was, by some accounts, brief or intermittent, possibly marked by disagreements with superiors. Following the war's conclusion in 1865, like many Southerners, he faced a changed world. He made an attempt to establish an art academy in Nashville, Tennessee, in collaboration with the painter George Dury, but this venture did not come to fruition. Such efforts highlight a desire to contribute to the artistic development of his region, though circumstances and perhaps his own temperament made sustained institutional involvement challenging.

The New York Years: A Shift to Intimate Symbolism

Disheartened by the lack of artistic opportunities in the post-war South, Newman relocated to New York City around 1865 or shortly thereafter. This move marked a significant turning point in his artistic direction. In New York, he largely abandoned portraiture and the pursuit of public commissions. Instead, he turned inward, focusing on small-scale easel paintings depicting imaginative, symbolic, religious, and mythological subjects.

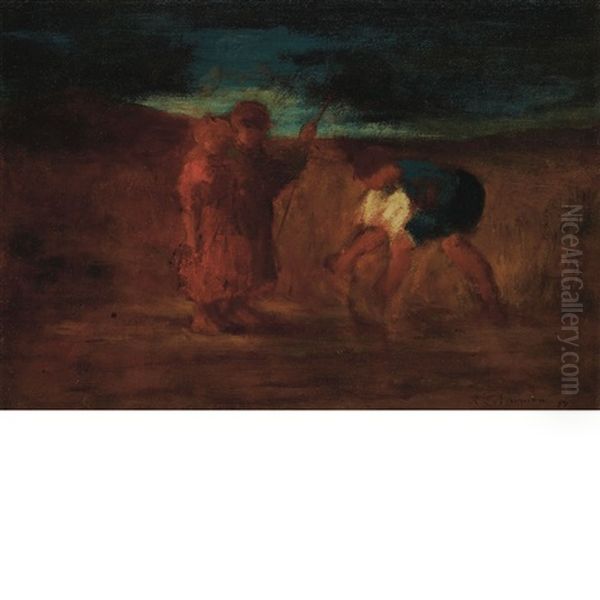

His canvases began to be populated by figures such as the Madonna and Child, Sappho, nymphs, fortune tellers, and characters from literature and the Bible. These were not grand, didactic history paintings but rather intimate, dreamlike visions. His style became increasingly personal, characterized by a rich, often dark, impasto, glowing, jewel-like colors that seemed to emerge from shadowy depths, and figures that were suggested rather than sharply defined. This highly individualized approach did not conform to the prevailing tastes for either the detailed realism of the later Hudson River School or the polished academicism favored by some.

During this period, Newman lived a reclusive, almost bohemian existence. He was known to be somewhat eccentric and was not an active participant in the mainstream art societies or exhibition circuits. This reclusiveness, while perhaps fostering his unique vision, also contributed to his lack of widespread recognition during his lifetime.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Romantic Affinities

Newman's mature style is a fascinating amalgamation of influences, thoroughly digested and transformed into something uniquely his own. The impact of the Barbizon School is evident in his tonal harmonies, his preference for mood over precise detail, and his often rustic or timeless settings. The rich, resonant color and dramatic lighting in his work also suggest an admiration for earlier Romantic masters like Eugène Delacroix. Delacroix's emphasis on color as an expressive force and his dynamic compositions find an echo in Newman's more intimate but equally emotive canvases.

Some critics have also pointed to the influence of Honoré Daumier, particularly in the expressive, sometimes distorted, quality of Newman's figures and his ability to convey character and emotion with a few deft strokes. While Daumier was a master of social satire, Newman channeled a similar expressive power towards more poetic and spiritual ends.

In New York, Newman found a kindred spirit in Albert Pinkham Ryder, another visionary painter known for his reclusive habits and his deeply personal, imaginative works. Both artists shared a Romantic sensibility, a preference for literary and biblical themes, and a technique that involved building up layers of paint to achieve rich, luminous surfaces. Along with figures like George Fuller and Ralph Albert Blakelock, Newman and Ryder are often grouped as key American "Romantic Realists" or "Visionary" painters who offered an alternative to the prevailing naturalism of the era. Elihu Vedder, with his symbolist and often literary-inspired compositions, also shares some thematic territory with Newman, though Vedder's style was generally more linear and detailed.

Newman's technique was distinctive. He often worked on small wood panels or canvases, applying paint thickly, sometimes with a palette knife, and allowing forms to emerge gradually from the richly worked surfaces. His figures are often simplified, their gestures and expressions conveying a sense of quiet contemplation, sorrow, or mystery. Color was paramount for Newman; he achieved remarkable luminosity and depth, with hues that seem to glow from within. His compositions, though often simple, are carefully balanced, with a strong sense of design.

Key Themes and Subjects in Newman's Oeuvre

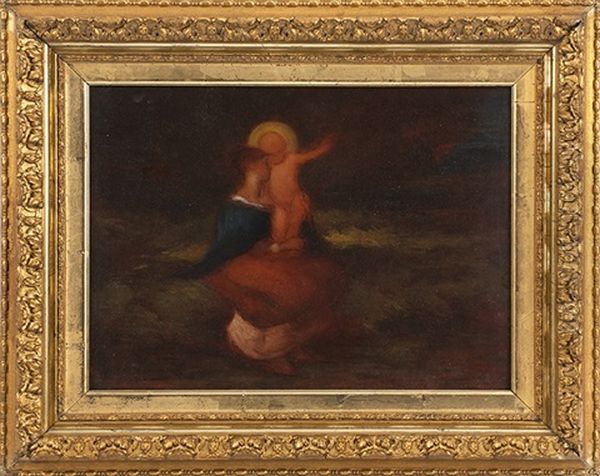

Newman's subject matter consistently revolved around themes that allowed for emotional and symbolic exploration. Religious subjects were prominent, particularly depictions of the Madonna and Child, Christ Stilling the Tempest, the Flight into Egypt, and the Good Samaritan. These were not conventional devotional images but rather personal interpretations imbued with a sense of human vulnerability and spiritual longing. His "Christ Stilling the Tempest," for example, focuses on the dramatic interplay of light and shadow and the emotional intensity of the scene, rather than on dogmatic illustration.

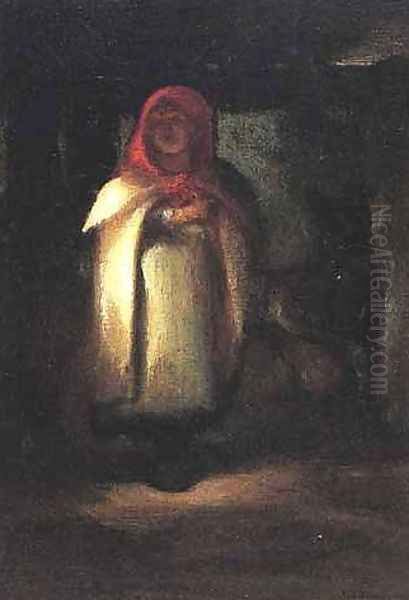

Literary and mythological themes also captivated him. Figures like Sappho, the ancient Greek poetess, appeared in his work, often depicted in moments of introspection or sorrow. Fairytales and folklore provided another source of inspiration, as seen in his well-known painting "Little Red Riding Hood." In this work, the familiar tale is transformed into a mysterious and slightly ominous encounter in a dark, atmospheric forest, the figures rendered with his characteristic suggestive brushwork.

He also painted more generalized allegorical or symbolic scenes, such as "The Fortune Teller," "The Bather," or "Harvest Time." These works, while not tied to specific narratives, evoke a sense of timelessness and explore universal human emotions. Even in these seemingly simpler themes, Newman's distinctive style—his rich color, his emphasis on mood, and his somewhat melancholic sensibility—is always present. His exploration of lithography in California, though brief due to costs, indicates an interest in graphic media, and he produced a few lithographs, one in three colors, before deciding to integrate these explorations more directly into his painting practice.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as representative of Newman's artistic achievement:

"Christ Stilling the Tempest" (c. 1885-1890): This powerful composition, exhibited at the Paris International Exposition in 1900 and later acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1914, showcases Newman's ability to handle dramatic subjects with emotional depth. The turbulent sea and the expressive figures are rendered with a focus on light and color to convey the scene's spiritual significance.

"Little Red Riding Hood" (1886): A quintessential Newman work, this painting transforms a familiar fairytale into a poetic and slightly unsettling vision. The rich, dark tones of the forest and the suggestive rendering of the figures create an atmosphere of mystery and enchantment. It is held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

"The Flight into Egypt" (various versions): A recurring theme in his work, these paintings depict the Holy Family's journey with a quiet pathos. The figures are often enveloped in a soft, atmospheric light, emphasizing their vulnerability and the sacredness of their mission.

"The Good Samaritan" (c. 1886): Another biblical scene treated with Newman's characteristic empathy and focus on human compassion. The figures are typically simplified, allowing the emotional core of the story to resonate.

"Sappho" (various versions): Depictions of the ancient poetess allowed Newman to explore themes of love, loss, and artistic inspiration. These works are often imbued with a melancholic beauty.

"Madonna and Child" (various versions): A frequent subject, Newman’s interpretations are tender and intimate, focusing on the human bond between mother and child, often set against richly colored, ambiguous backgrounds.

"The Bather" (c. 1890s): This work, like others with similar generic titles, allowed Newman to focus on the human form within an atmospheric, often natural, setting, emphasizing color and mood over narrative specificity.

"Adam and Eve" (1874): An early example of his engagement with biblical themes, likely exploring the profound human drama of the Genesis story.

These works, and many others, reveal an artist consistently dedicated to his personal vision, creating a body of work that is both cohesive and deeply felt.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Reclusive Nature

Despite the quality and originality of his work, Robert Loftin Newman remained largely outside the mainstream art world and received limited recognition during his lifetime. He was not a prolific exhibitor. In fact, he is known to have had only two solo exhibitions: one at the Knoedler Gallery in New York in 1894, and another at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1906.

His reclusive lifestyle undoubtedly played a role in his relative obscurity. He was not one to actively promote his work or cultivate relationships with influential critics or patrons. However, he was not entirely isolated. He had friendships with fellow artists, including William Morris Hunt, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and William M. Marshall (who, like Newman and Hunt, had studied with Couture). His connection with Hunt was particularly significant, providing a link to the Barbizon painters and to a broader circle of artists.

The exhibition of "Christ Stilling the Tempest" at the Paris International Exposition in 1900 was a notable moment of international exposure, though it did not dramatically alter his standing at home. It was primarily in the years following his death that his work began to be more seriously assessed and appreciated by collectors, critics, and museums.

Later Years, Death, and Posthumous Legacy

Robert Loftin Newman continued to paint in his New York studio, pursuing his singular vision into his later years. His life ended tragically on March 31, 1912, when he died from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning in his New York City apartment. He was eighty-four years old.

The posthumous recognition that had eluded him in life began to grow, albeit slowly. A key moment was the acquisition of "Christ Stilling the Tempest" by the Brooklyn Museum in 1914. This marked an important institutional validation of his work. Over the following decades, his paintings found their way into other significant public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and various museums in Richmond, Nashville, and other locations.

Scholarly interest also increased, with his work being included in studies of American Romanticism and Symbolism. Art historians began to recognize him as an important, if unconventional, voice in American art, an artist who, like Ryder, forged a deeply personal path, independent of prevailing trends. His influence can be seen as part of a lineage of American visionary painters, artists who prioritized inner experience and poetic expression over objective representation. His dedication to color as an emotional and spiritual force also aligns him with later developments in modern art.

Conclusion: A Quietly Resonant Voice

Robert Loftin Newman's art offers a window into a deeply introspective and poetic sensibility. Working on an intimate scale, he created a world of dreamlike beauty, suffused with rich color and quiet emotion. Though influenced by European masters like Delacroix and the Barbizon painters, particularly Millet and Corot, and sharing affinities with American contemporaries like Ryder and Fuller, Newman's voice was distinctly his own. He was an artist who valued personal vision above public acclaim, content to explore his chosen themes of spirituality, literature, and myth in a style that was both timeless and intensely personal.

His legacy is that of an artist's artist, perhaps, one whose subtle but profound contributions to American art have gained increasing appreciation over time. In a period often dominated by grand landscapes and societal portraits, Newman offered a more private, contemplative art, one that continues to resonate with viewers who seek a deeper, more poetic engagement with the painted image. His life and work serve as a reminder that artistic significance is not always measured by contemporary fame but by the enduring power of a unique and authentic vision. His paintings, though often small in size, possess a remarkable depth and luminosity, securing his place as a significant, if often overlooked, master of American Romantic and Symbolist art.