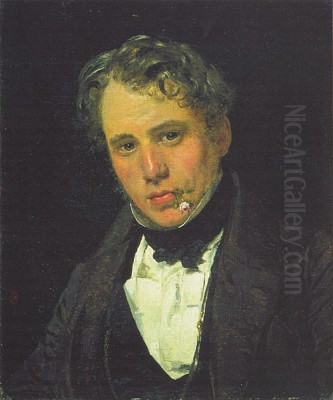

Wilhelm Nicolai Marstrand stands as one of the most significant and versatile figures of the Danish Golden Age of painting. Born in Copenhagen on December 24, 1810, and passing away in the same city on March 25, 1873, Marstrand's career spanned a crucial period of artistic development in Denmark. He was not only a prolific painter and illustrator but also an influential educator, leaving an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists. His work is celebrated for its vibrant depictions of everyday life, its engagement with historical and literary themes, and its masterful absorption of international influences, particularly from Italy. Marstrand navigated the artistic currents of his time with remarkable skill, producing a body of work characterized by keen observation, narrative flair, and often, a distinct sense of humor.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Wilhelm Marstrand was born into an environment that appreciated craftsmanship and intellect. His father, Nicolai Jacob Marstrand, was a respected instrument maker and inventor, while his mother was Petra Othilia Smith. This background perhaps fostered an appreciation for precision and ingenuity. Marstrand initially attended the prestigious Metropolitan School (Metropolitanskolen) in Copenhagen, but his academic inclinations soon gave way to a passion for art.

He enrolled at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts around 1825, becoming a student of the central figure of the Golden Age, Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg. Eckersberg, often called the "Father of Danish Painting," emphasized meticulous observation, clear composition, and a sober realism grounded in studies from life and nature. While Marstrand absorbed these foundational principles, his own artistic temperament leaned towards greater dynamism and narrative complexity than typically found in Eckersberg's more restrained classicism.

Despite his evident talent, Marstrand did not achieve the highest academic accolades easily. He competed for the Academy's large gold medal – a prize that usually included a substantial travel stipend – in both 1833 and 1835, but was unsuccessful on both occasions. However, his abilities were recognized, and he did receive financial support through travel grants, enabling the journeys that would prove pivotal to his artistic development. His early works already showed promise in genre scenes and historical subjects, hinting at the breadth of his future interests.

The Italian Journeys: A Catalyst for Color and Romanticism

Like many Northern European artists of his era, Marstrand felt the powerful allure of Italy. He undertook several extended trips south, beginning in 1836, visiting Germany before spending significant time in Rome, Naples, and Venice. These journeys were transformative, profoundly shaping his artistic vision and technical approach. Italy offered not just classical ruins and Renaissance masterpieces but a vibrant contemporary culture that captivated him.

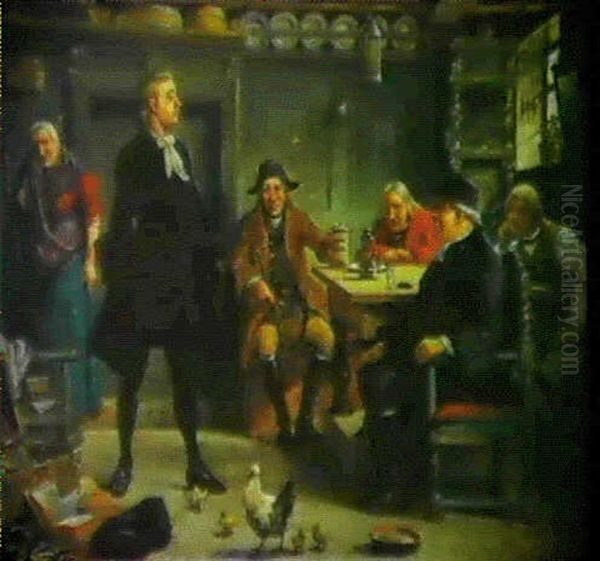

In Italy, Marstrand discovered a world bathed in warmer light and richer color than the often-grey skies of Denmark. He was particularly drawn to the everyday life of ordinary Italians – their festivals, their work, their social interactions in osterias and public squares. This contrasted with the more common focus of visiting artists on grand architecture or historical reenactments. His Italian genre scenes are imbued with a sense of energy, spontaneity, and romanticism. He developed a looser brushstroke and a more expressive use of color to capture the vivacity he witnessed.

Works like Italiensk Osteria Scene (Italian Osteria Scene, 1839) or Romerske borgere forsamlede til lystighed i et osteri (Roman Citizens Gathered for Merriment in an Osteria, 1839) exemplify this period. They depict lively gatherings filled with animated figures, showcasing his skill in composing complex multi-figure scenes and capturing individual character and emotion. Another famous work stemming from these experiences is his depiction of the Oktoberfest (October Festival) in Rome, brimming with festive energy. His focus, especially noted in his Venetian scenes, was often on the people – the fishermen, the common folk – rather than solely on the famous cityscapes, adding a humanistic dimension to his Italian oeuvre. These works were sent back to Denmark and received considerable acclaim, establishing his reputation.

Master of Danish Genre and Narrative Painting

Upon returning to Denmark, Marstrand applied his sharpened skills and broadened perspective to Danish subjects, becoming a leading painter of genre scenes. He possessed a remarkable ability to observe and depict the nuances of Danish society, particularly the life of the Copenhagen bourgeoisie. His scenes are often characterized by a gentle humor, psychological insight, and a strong narrative element, frequently drawing inspiration from literature and theatre.

He became particularly associated with illustrating the comedies of Ludvig Holberg, the great Dano-Norwegian playwright often compared to Molière. Marstrand brought Holberg's satirical characters and situations to life with visual wit and understanding. His painting depicting a scene from Holberg's Erasmus Montanus, submitted for his membership to the Academy in 1843, was a significant success. He also created memorable scenes from plays like Den Lykkelige Skibbrud (The Fortunate Shipwreck). These works resonated deeply with the Danish public, who cherished Holberg's plays as national cultural treasures.

Beyond literary subjects, Marstrand captured everyday Danish life with warmth and detail. En musikalsk Aftensoiree (A Musical Evening Party), depicting a gathering in a bourgeois home, is celebrated for its lively atmosphere and individualized character portrayals. He also traveled within Scandinavia, notably to Sweden, where he painted scenes of rural life, such as his series depicting Dalecarlian peasants (the Dalkarl series), showing his interest extended beyond urban settings. Through these works, Marstrand provided a rich visual chronicle of his time, marked by empathy and a keen eye for human interaction.

Historical Painting and Monumental Commissions

While renowned for genre painting, Marstrand also harbored ambitions in the more prestigious field of historical painting, a genre highly valued by academic institutions. His Italian experiences had exposed him to the grand traditions of Renaissance and Baroque history painting, and he sought to contribute to this genre within a Danish context. His historical works often combined dramatic storytelling with careful attention to period detail.

Later in his career, Marstrand increasingly turned towards large-scale public commissions and religious themes. This shift may have been influenced by personal circumstances, including the death of his wife, Margrethe Christine Weidemann, which reportedly led him to explore more profound subjects. It also reflected his senior status within the Danish art establishment.

His most significant monumental works include large murals for the chapel of Christian IV in Roskilde Cathedral, the traditional burial site of Danish monarchs. These paintings depict key scenes from the life of this famous Danish king. He also undertook important religious commissions, such as a major altarpiece for Faaborg Church. These later works demonstrate his ability to handle complex compositions on a grand scale and engage with serious historical and spiritual themes, solidifying his position as a versatile master capable of working across different genres and formats.

The Portraitist's Eye

Alongside his narrative and historical works, Marstrand was a sought-after portrait painter. He applied his keen observational skills and psychological insight to capture the likenesses and personalities of his sitters. His subjects included family members, fellow artists, and prominent figures in Danish society.

His portraits often possess an immediacy and liveliness that distinguishes them from more formal academic portraiture. He painted fellow artist Carl Heinrich Bloch, capturing a sense of collegial connection. Family portraits, such as the charming painting of Otto Marstrand's Two Daughters and their West Indian Nurse (1857), reveal a more intimate side of his work, showcasing his ability to depict personal relationships and domestic settings with sensitivity. He also painted a portrait of his mother, Petra Otillia Smith, and his daughter, Justina Antoine, appeared in some of his works. These portraits contribute significantly to our understanding of the social and cultural milieu of the Danish Golden Age.

Academician, Educator, and Influential Figure

Marstrand's contributions to Danish art extended beyond his own canvases. He became a member of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1843 and was appointed professor there in 1848. He served as the Academy's director for two separate terms (1853-1857 and 1863-1873), holding a position of significant influence within the Danish art world. He was also honored with the title of State Councillor (Etatsråd), reflecting his high standing.

As an educator, Marstrand played a crucial role in shaping the next generation of Danish artists. He was known for encouraging students to develop their individual talents rather than strictly adhering to a single method. Among his most famous pupils were Peder Severin Krøyer and Michael Ancher, both of whom would become leading figures of the Skagen Painters, a group that moved Danish art towards Realism and Impressionism later in the 19th century. Marstrand's emphasis on lively depiction and capturing the effects of light, particularly evident in his Italian works, likely provided a valuable foundation for these future innovators. His teaching philosophy, focused on nurturing individual skill and interest, had a lasting impact.

Artistic Context and Contemporaries

Marstrand operated within a vibrant artistic community during the Danish Golden Age (roughly the first half of the 19th century). His teacher, C.W. Eckersberg, set the standard for the period's emphasis on realism and meticulous study. Marstrand's generation included other highly talented painters who explored different facets of Danish life and landscape. Christen Købke is celebrated for his sensitive depictions of the outskirts of Copenhagen and his subtle handling of light. Constantin Hansen, like Marstrand, traveled extensively in Italy and became known for his architectural studies, portraits, and ambitious historical compositions, including monumental decorations for the University of Copenhagen.

Martinus Rørbye was another inveterate traveler, venturing not only to Italy and Greece but also to Norway and Turkey, bringing an exotic flavor to Danish painting. J.Th. Lundbye and Dankvart Dreyer were masters of the Danish landscape, capturing the specific moods and features of the Zealand and Jutland countrysides with national romantic sentiment. Vilhelm Kyhn, another contemporary, was also a prominent landscape painter and influential teacher. The towering figure of sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, who spent much of his career in Rome but whose return to Copenhagen in 1838 was a major cultural event, also defined the neoclassical taste of the era. Marstrand interacted with these figures, contributing his unique blend of narrative skill, humor, and international perspective to this rich artistic environment. His relationship with Carl Bloch, whom he painted, signifies the connections within this relatively close-knit art scene. His influence extended to the Skagen painters like P.S. Krøyer, Michael Ancher, and indirectly, Anna Ancher, bridging the Golden Age with later movements.

Later Years, Legacy, and Unresolved Questions

Marstrand remained active as an artist and educator until late in his life. However, his health declined significantly after suffering a stroke (described as a cerebral hemorrhage) in 1871, which resulted in partial paralysis. This undoubtedly impacted his ability to work during his final years. He passed away in Copenhagen in 1873 at the age of 62.

Wilhelm Marstrand's legacy is that of a central and highly versatile figure in Danish art. He excelled in multiple genres, from intimate genre scenes and portraits to large-scale historical and religious commissions. His work captured the spirit of his time, reflecting both the everyday realities and the cultural aspirations of 19th-century Denmark. His Italian journeys were crucial, infusing Danish art with Mediterranean light, color, and vitality. As an educator, he nurtured key talents who would lead Danish painting into new directions.

While immensely popular during his lifetime, Marstrand's reputation, like that of some other Golden Age painters, experienced a period of relative neglect in the early 20th century as modernist aesthetics took hold. However, subsequent reappraisals have firmly re-established his importance. Today, he is recognized as one of the pillars of the Danish Golden Age.

Certain aspects of his life and work continue to invite discussion. The sheer diversity of his output – ranging from humorous genre scenes to solemn religious works – raises questions about the underlying unity of his artistic vision. Was there an internal tension between his popular, humorous side and his academic, historical ambitions? His deep fascination with Italy, while artistically fruitful, prompts consideration of its personal significance beyond the purely aesthetic. Some scholars have noted potential controversies, such as the inclusion of nude figures in some religious contexts, possibly challenging contemporary norms. The impact of his late-life illness on his final works also remains a subject for consideration. These complexities add depth to our understanding of Marstrand as both an artist and an individual navigating the cultural landscape of his time.

Conclusion: A Cornerstone of Danish Art

Wilhelm Nicolai Marstrand remains a vital and engaging figure in the history of Danish art. His ability to move seamlessly between humorous observation, historical drama, intimate portraiture, and grand public statements marks him as an artist of exceptional range. He absorbed the lessons of his teacher Eckersberg but forged his own path, enriched by his transformative experiences in Italy. His paintings offer a vivid window into the Danish Golden Age, capturing its social life, cultural preoccupations, and artistic dialogues. Through his own prolific output and his influence as a teacher, Marstrand played an indispensable role in shaping the course of Danish art, leaving behind a legacy characterized by technical brilliance, narrative power, and an enduring connection to the human experience.