William Blake stands as one of the most singular and enigmatic figures in the history of English art and literature. Born in London in 1757, during a period poised between the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason and the burgeoning Romantic movement's celebration of emotion and the individual spirit, Blake forged a path entirely his own. He was a poet, painter, and printmaker whose work defied easy categorization, blending profound spiritual insight with fierce social critique, and visual art with poetic verse in a way unprecedented in his time and rarely matched since.

Though largely unrecognized and often misunderstood during his lifetime, Blake's influence has grown immeasurably since his death in 1827. He is now celebrated as a key figure of early Romanticism, a visionary artist whose explorations of the human psyche, mythology, religion, and the power of the imagination continue to resonate. His life and work offer a compelling study in artistic integrity, spiritual conviction, and the struggle of a unique creative force against the conventions of his age.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

William Blake was born in the bustling Soho district of London, the third of seven children. His father was a hosier, placing the family within the city's artisan class. Unlike many artists of his stature, Blake did not receive a formal university education. His parents, recognizing his artistic inclinations and perhaps his unique temperament early on, opted for homeschooling, primarily under his mother Catherine's guidance. She taught him to read and write, and the Bible became an early and enduring influence on his imagination.

From a young age, Blake reported experiencing visions – seeing angels among the haymakers in the fields or God's face appearing at his window. While these accounts startled his parents, they chose not to suppress his vivid inner life, a decision crucial for his later artistic development. His formal artistic training began at age ten when he was enrolled in Henry Pars's drawing school. Here, he learned to sketch the human figure by copying plaster casts of classical sculptures, developing the strong linear quality that would characterize much of his later work.

At fourteen, Blake's path diverged from traditional fine art training. Instead of pursuing painting at the Royal Academy immediately, he was apprenticed to the engraver James Basire. This seven-year apprenticeship (1772-1779) was formative. Engraving was a demanding craft requiring precision and discipline, skills Blake mastered thoroughly. Basire, known for his somewhat antiquarian style, sent Blake to sketch the Gothic tombs and monuments in Westminster Abbey. This immersion in medieval art deeply affected Blake, fostering his appreciation for linear forms, spiritual intensity, and non-classical aesthetics, setting him apart from the prevailing Neoclassical tastes promoted by figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds, the President of the Royal Academy.

The Royal Academy and Early Career

Upon completing his apprenticeship in 1779, Blake briefly enrolled as a student at the Royal Academy of Arts. However, his independent spirit and already well-formed artistic ideas clashed with the institution's rigid doctrines. He particularly disliked the emphasis on the painterly styles of artists like Rubens and Titian, championed by Reynolds. Blake preferred the clear outlines and imaginative power he found in Raphael and Michelangelo, as well as in Gothic art. His time at the Academy was short-lived and marked by friction; he famously expressed contempt for Reynolds's teachings, finding them detrimental to true artistic inspiration.

Leaving the Academy, Blake began working as a commercial engraver, producing illustrations for books and magazines. This work provided a modest income but was often creatively unfulfilling. He engraved works after other artists, such as Thomas Stothard and Henry Fuseli, the latter becoming a significant friend and influence. Fuseli, a Swiss-born painter known for his dramatic and often nightmarish subjects, shared Blake's interest in the sublime and the imaginative, encouraging Blake's own visionary tendencies. Blake also associated with other artists like the sculptor John Flaxman, whose Neoclassical linearity resonated with Blake's own style, though their imaginative worlds differed.

In 1782, Blake married Catherine Sophia Boucher. Though illiterate at the time of their marriage (Blake taught her to read and write), Catherine became an invaluable partner. She assisted him in his printing workshop, helped colour his illuminated books, and provided unwavering emotional and practical support throughout his often-difficult life. Their marriage, though childless, was by all accounts a deep and enduring companionship, a source of stability in Blake's unconventional world.

Innovations in Printmaking: The Illuminated Books

Perhaps Blake's most radical contribution to the visual arts was his invention of "relief etching" or "illuminated printing." Developed around 1788, this technique allowed him to combine his poetry and designs on the same copper plate, creating unified works of text and image that he called "illuminated books." Unlike traditional intaglio etching or engraving where the lines to be printed are incised into the plate, Blake wrote his text and drew his designs directly onto the plate using an acid-resistant substance. When the plate was submerged in acid, the unprotected areas were eaten away, leaving the text and design standing in relief, like type.

This method gave Blake complete creative control over his productions, bypassing the need for commercial typesetters and publishers. He could print the plates himself in his workshop, often in monochrome, and then he and Catherine would hand-colour the pages with watercolour, making each copy a unique work of art. This fusion of word and image was central to Blake's vision, allowing for a complex interplay where text and design illuminate each other.

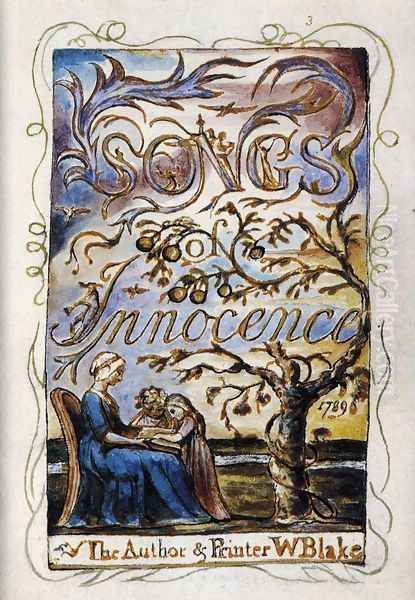

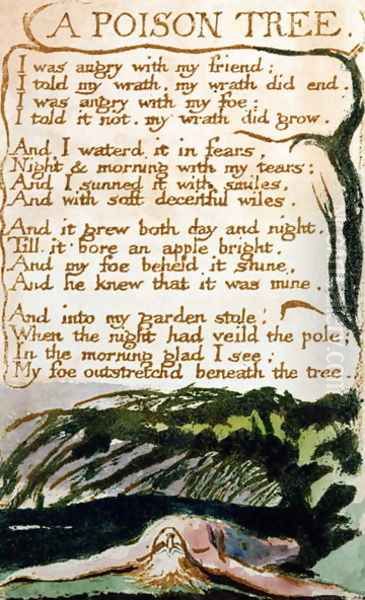

The first major products of this technique were Songs of Innocence (1789) and its counterpart, Songs of Experience (1794), later issued together as Songs of Innocence and of Experience Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul. These collections contain some of Blake's best-loved poems, such as "The Lamb," "The Tyger," and "London." Innocence explores states of naive purity, childhood wonder, and harmony with nature, often depicted with flowing lines and bright colours. Experience, conversely, delves into the harsh realities of adult life, social injustice, oppression, and the loss of innocence, often employing darker tones and more angular, constrained compositions. Together, they represent Blake's concept of the "contraries" – opposing forces necessary for human existence.

The Prophetic Books: Mythology and Vision

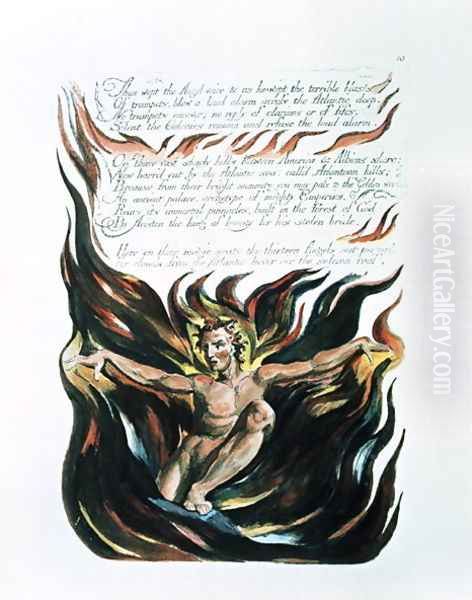

Following the Songs, Blake embarked on a series of longer, more complex illuminated works often referred to as the "Prophetic Books." These challenging works articulate Blake's unique and intricate personal mythology, populated by figures like Urizen (representing reason and law), Los (imagination and time), Orc (revolutionary energy), and Albion (the primordial giant representing humanity or England). In these books, Blake explored cosmic history, the fall of humanity, the critique of oppressive religious and political systems, and the potential for spiritual regeneration through imagination.

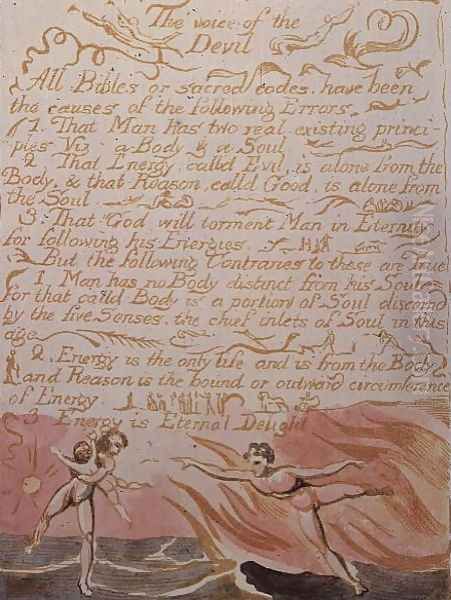

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (c. 1790-93) is a provocative satire challenging conventional notions of good and evil, arguing that energy (Hell) is as vital as reason (Heaven). It contains the famous "Proverbs of Hell," offering maxims that celebrate impulse and desire over restraint. Works like America a Prophecy (1793) and Europe a Prophecy (1794) engage directly with the revolutionary spirit of the age, interpreting the American and French Revolutions within Blake's mythological framework, often sympathizing with the forces of liberation against tyranny.

Later prophetic works, such as The Book of Urizen (1794), Milton a Poem (c. 1804-1810), and his longest work, Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion (c. 1804-1820), become increasingly dense and visionary. They depict vast cosmic struggles, the fragmentation and potential reunification of the human spirit, and Blake's relentless quest for spiritual truth outside the confines of established religion. These books, with their powerful designs and complex narratives, represent the culmination of Blake's illuminated printing technique and his highly personal cosmology.

Themes of Blake's Art and Poetry

Several core themes permeate Blake's diverse body of work. Central is the power of the Imagination. For Blake, imagination was not mere fancy but the divine faculty within humanity, the primary means of perceiving spiritual reality and achieving redemption. He contrasted it sharply with fallen reason (personified by Urizen), which he saw as limiting, oppressive, and responsible for the "mind-forg'd manacles" that enslave humanity.

Spirituality versus Organized Religion is another crucial theme. While deeply religious and steeped in the Bible, Blake was fiercely critical of the established Church and orthodox Christianity, which he viewed as hypocritical and life-denying. He sought a more direct, personal relationship with the divine, emphasizing inner revelation and the inherent divinity within all things. His works often reinterpret biblical narratives and characters through his own visionary lens.

Social and Political Critique runs strongly through Blake's work. Living in a time of revolution, industrialization, and widespread poverty, he was acutely aware of social injustice. Poems like "London" lament the suffering and oppression he witnessed in the city. He criticized the exploitation of children (as in "The Chimney Sweeper"), the horrors of war, and the dehumanizing effects of industrial society. His sympathies often lay with the oppressed and the rebellious, challenging the authority of state and church.

The concept of Contraries – innocence and experience, reason and energy, mercy and justice – is fundamental to Blake's thought. He believed these opposing forces were not simply good versus evil but necessary components of existence. True spiritual wholeness, for Blake, involved the integration, not the suppression, of these contraries.

Blake as Painter and Illustrator

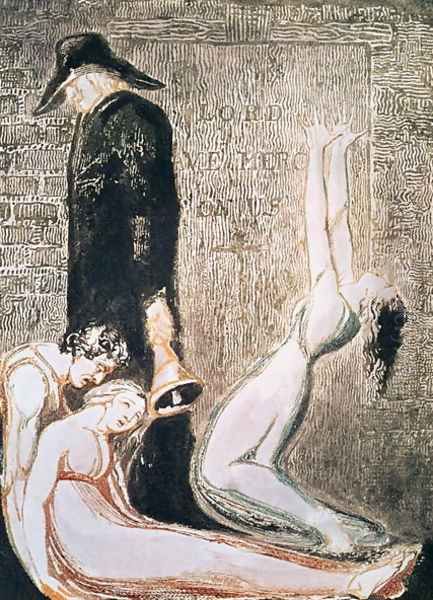

Beyond his illuminated books, Blake worked extensively as a painter and illustrator, primarily using watercolour and tempera over a gesso-like ground on panel or canvas, a technique he called "fresco." His visual style remained distinct: strong, wiry outlines defining muscular, often elongated figures, dynamic and energetic compositions, and a preference for visionary and sublime subject matter over naturalistic representation. His influences included Michelangelo's powerful figures, the linear grace of Gothic art, and the imaginative intensity of Mannerist painters.

He undertook several major series of illustrations for existing literary works. In the mid-1790s, he produced over 500 designs for Edward Young's Night Thoughts, though only a fraction were published. He created powerful illustrations for the poems of Thomas Gray and later for John Milton's Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, and On the Morning of Christ's Nativity.

Two of his most significant late commissions came through the patronage of the artist John Linnell. Around 1821, Linnell commissioned Blake to create a series of engravings illustrating the Book of Job. The resulting 22 plates are considered among the pinnacles of Blake's artistry and religious interpretation, tracing Job's spiritual journey from suffering and doubt to revelation. Following this success, Linnell commissioned Blake to illustrate Dante's Divine Comedy. Blake, then in his late sixties, threw himself into the project with passion, learning Italian to read Dante in the original. He produced over 100 watercolour designs, full of visionary intensity and dramatic power, before his death left the engraving process incomplete.

Relationships, Patronage, and 'The Ancients'

Blake's unconventional art and ideas meant he struggled financially for much of his life. He relied on a small circle of patrons and friends. Thomas Butts, a clerk in the Muster-Master General's office, was perhaps his most consistent patron from around 1799. Butts commissioned numerous works, particularly a series of biblical watercolours and tempera paintings, providing Blake with a crucial source of income and demonstrating genuine appreciation for his unique vision.

The painter and engraver John Linnell became a vital figure in Blake's later years. Meeting Blake in 1818, Linnell not only commissioned the Job and Dante series but also introduced him to a group of younger artists who revered him. This group, who called themselves "The Ancients," included Samuel Palmer, Edward Calvert, and George Richmond. They were deeply inspired by Blake's visionary art and spiritual intensity, finding in him an antidote to the materialism of the age. They gathered around the elderly Blake in his final years, offering friendship, admiration, and practical support. Samuel Palmer, in particular, absorbed Blake's influence into his own intensely poetic landscape paintings of the Shoreham period.

Blake's relationships within the broader London art world were often complex. He maintained friendships with figures like Fuseli and Flaxman but could also be critical and isolated. He clashed with publishers and engravers like Robert Cromek, whom he accused of stealing his ideas. His outspokenness and visionary claims led many contemporaries to dismiss him as eccentric or even mad, a perception that hampered his professional prospects. Figures within the establishment, like the successful portraitist Sir Thomas Lawrence or the landscape giants J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, occupied vastly different artistic spheres, though all were part of the broader Romantic sensibility sweeping through British art. Blake's path, however, remained resolutely internal and visionary, distinct from Constable's focus on empirical nature or Turner's atmospheric effects.

Reception and Legacy

During his lifetime, William Blake remained largely on the margins of the art and literary worlds. His poetry was privately printed and circulated little; his exhibitions, like the one he held above his brother's shop in 1809, were poorly attended and met with critical hostility or indifference. He died in 1827 in relative poverty, known only to a small circle of admirers. His wife Catherine continued to believe in his genius, preserving his works after his death.

Blake's rediscovery began in earnest with the publication of Alexander Gilchrist's Life of William Blake, 'Pictor Ignotus' in 1863. This biography brought Blake's life and work to wider attention and sparked interest among a new generation, particularly the Pre-Raphaelites. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a key figure in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, was an early enthusiast, acquiring one of Blake's manuscript notebooks and helping to edit selections of his poetry. Blake's emphasis on spirituality, medievalism, detailed symbolism, and the integration of art and craft resonated with Pre-Raphaelite ideals, influencing artists like Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Blake's reputation grew steadily. Symbolist artists and writers admired his visionary mysticism. The Irish poet W.B. Yeats saw Blake as a crucial precursor and edited his works. In the 20th century, Blake's influence permeated various fields. Surrealists like Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí recognized a kindred spirit in his exploration of the subconscious and dreamlike imagery. Writers from Aldous Huxley (who took the title The Doors of Perception from Blake's Marriage of Heaven and Hell) to Beat poets like Allen Ginsberg drew inspiration from his prophetic voice and critique of conformity. Composers like Ralph Vaughan Williams and Benjamin Britten set his poetry to music. His ideas and images entered counter-culture movements in the 1960s.

Today, William Blake is firmly established as a major figure in both English literature and British art. His illuminated books are treasured as unique fusions of poetry and visual design. His paintings and engravings are admired for their imaginative power and technical skill. His complex mythology continues to be studied and debated. Artists like Pablo Picasso have acknowledged his influence. His work appears referenced in modern graphic novels and popular culture, demonstrating his enduring relevance.

Conclusion: The Enduring Visionary

William Blake's journey was one of extraordinary artistic and spiritual independence. In an age often dominated by reason or classical restraint, he championed the power of the imagination and the validity of inner vision. He created a unique artistic language, seamlessly blending poetry and visual art in his illuminated books, and developed a complex personal mythology to explore the deepest questions of existence, spirituality, and society.

Though often dismissed or ignored by his contemporaries, Blake's fierce integrity and unwavering commitment to his vision ultimately secured his legacy. He challenged the artistic, religious, and political conventions of his time, producing a body of work that remains profoundly original and deeply moving. As a poet, painter, printmaker, and prophet of the imagination, William Blake carved out a unique space in cultural history, leaving behind a universe of images and ideas that continue to inspire, provoke, and enchant. His life and work stand as a testament to the enduring power of the individual creative spirit.