William Collins stands as a significant figure in the landscape of early 19th-century British art. Active during a period of profound change and artistic innovation, he carved a distinct niche for himself through his sensitive portrayals of coastal scenery and the simple narratives of rural life. While perhaps overshadowed in posthumous fame by titans like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, Collins enjoyed considerable success and acclaim during his lifetime, captivating audiences with his charming, meticulously rendered canvases. His work offers a valuable window into the social fabric and natural beauty of England, particularly its shorelines and the lives of its humbler inhabitants.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in London in 1787, William Collins entered a world connected to the arts. His father, also named William, was an Irish-born picture dealer and writer, providing the young Collins with early exposure to the art world. His mother was also of Irish descent. This familial connection proved formative. A crucial early influence was the painter George Morland, a friend of Collins senior known for his own rustic scenes and animal paintings. Under Morland's informal guidance, the young Collins began to develop his artistic skills, absorbing an appreciation for rural subjects and naturalistic observation that would echo throughout his career.

The lure of a formal artistic education led Collins to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1807. This institution was the epicentre of the British art establishment, presided over by figures like Benjamin West and later Sir Thomas Lawrence. Enrolling at the Academy provided Collins with rigorous training in drawing and painting, exposing him to the works of Old Masters and the standards of academic excellence. It was a critical step in honing his craft and preparing him for a professional career.

Emergence at the Royal Academy

Collins did not wait long to make his mark. In 1809, he made his debut at the Royal Academy's annual exhibition, a crucial venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage. He presented two works: Boy at Breakfast (also cited as Breakfast in the Boy's Room) and Boy with a Bird's Nest. These early submissions already hinted at his preferred subject matter – the innocence of childhood intertwined with the details of everyday rural life. They were well-received, signalling the arrival of a promising new talent.

Although some sources suggest he initially explored portraiture, Collins quickly found his true calling in landscape and genre painting. He was particularly drawn to the lives of ordinary people, especially children, fishermen, and farming families, often depicting their interactions with the natural world. His approach combined careful observation with a gentle sentimentality that resonated with contemporary tastes, distinguishing his work from the more dramatic or sublime landscapes favoured by some of his peers. His success grew steadily within the Academy framework.

The Coastal Visionary

A defining characteristic of Collins's oeuvre is his fascination with the English coastline. He undertook numerous sketching tours, particularly to the coasts of Norfolk, Kent, and Sussex, including favoured spots like Hastings and Cromer. These trips provided him with a wealth of material and a deep understanding of coastal light, atmosphere, and the daily lives of fishing communities. His first significant visit to the coast around 1815 marked a turning point, solidifying this thematic focus.

His coastal scenes are celebrated for their clarity, luminosity, and meticulous detail. Works like Scene on the Norfolk Coast (dated variously, possibly 1815 or 1825, now in the Royal Collection) exemplify his ability to capture the expansive beaches, the quality of seaside light, and the activities of local people – children playing, fishermen tending their boats or nets. He rendered the textures of sand, water, and sky with remarkable fidelity, often under bright, clear conditions, though he could also depict more atmospheric effects. Unlike the turbulent seascapes of Turner, Collins often focused on the calmer, more domestic aspects of coastal life.

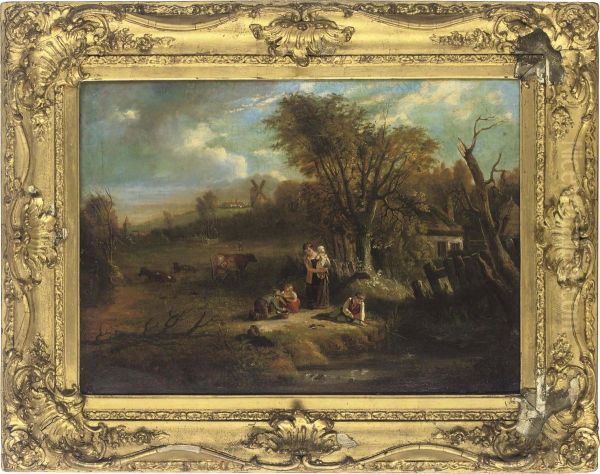

Master of Rural Genre

Alongside his coastal paintings, Collins excelled in rural genre scenes. These works typically feature picturesque cottages, farmyards, and village settings, populated by children, families, and animals. He possessed a keen eye for narrative detail, creating vignettes that told simple, often heartwarming stories. Themes of childhood innocence, rustic piety, family bonds, and the quiet dignity of labour recur throughout his work.

Paintings such as The Sale of the Pet Lamb (exhibited 1813) became immensely popular. This work, depicting the poignant moment a family sells a beloved lamb, struck a chord with audiences for its blend of sentiment and social observation. Similarly, Rustic Civility (1833) captures a charming interaction between country children and perhaps a passing traveller, highlighting themes of innocence and simple manners. Happy as a King (1836), showing children joyfully playing on a gate in a sunlit landscape, is another quintessential Collins piece, radiating cheerfulness and idyllic charm. These works cemented his reputation as a master of depicting the tender moments of rural existence.

Artistic Style and Technique

Collins's style is characterized by careful draughtsmanship, a clear, bright palette, and a high degree of finish. His brushwork is typically precise and controlled, allowing for the detailed rendering of figures, foliage, textures, and atmospheric effects. He was particularly adept at capturing the effects of natural light, often favouring sunny, open-air scenes that allowed him to explore subtle variations in tone and colour. This clarity and luminosity became hallmarks of his work.

While grounded in careful observation of nature, Collins's paintings also possess a distinct Romantic sensibility. They often evoke a sense of nostalgia for a simpler, perhaps idealized, rural past. The sentimentality, while sometimes criticized by later generations, was a key element of their appeal to contemporary audiences. He managed to infuse his scenes with genuine feeling without lapsing into excessive melodrama. His compositions are typically well-balanced and harmonious, creating a sense of order and tranquility. He learned much from 17th-century Dutch genre painters but adapted their models to a distinctly English context and sensibility.

Italian Interlude and Later Career

In 1837, Collins embarked on a significant journey, travelling to Italy with his family, including his eldest son, Wilkie Collins, who would later achieve fame as a novelist. They spent nearly two years abroad, primarily in Rome and Naples. This trip exposed Collins to the landscapes, culture, and art of Italy, inspiring a new range of subjects. He painted scenes of Italian peasant life, religious festivals, and picturesque landscapes, which he exhibited upon his return to England.

While these Italian works were noted for their colour and exotic themes, they did not fundamentally alter his established reputation, which remained rooted in his English subjects. Some critics felt they lacked the authentic charm of his native scenes. Nevertheless, the experience broadened his artistic horizons. Upon his return, his position within the art establishment was further solidified when, in 1840, he was appointed Librarian of the Royal Academy, a post of considerable trust and responsibility.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Collins operated within a vibrant and competitive London art world. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy and the British Institution alongside the leading artists of his day. His popularity was such that, for a time, his works commanded prices and attention that rivalled, or even occasionally surpassed, those of John Constable and J.M.W. Turner. He maintained friendships and professional connections with many artists. For instance, he collaborated with the Scottish painter Hugh William 'Grecian' Williams on occasion and was friendly with Sir David Wilkie, whose own genre scenes were hugely influential.

His relationship with Constable is particularly noteworthy. Both artists were dedicated to landscape and drew inspiration from the English countryside, yet their approaches differed significantly. Constable's work was often bolder, more expressive in its brushwork, and focused on capturing the fleeting effects of weather and light with a revolutionary naturalism. Collins's style was generally tighter, more detailed, and imbued with a clearer narrative or sentimental element. While both achieved RA status (Collins elected ARA in 1814, RA in 1820; Constable ARA 1819, RA 1829), their paths and ultimate legacies diverged. Collins also interacted with figures like the marine painter Clarkson Stanfield, the topographical artist David Roberts, the animal painter Sir Edwin Landseer, and fellow landscape painters such as Augustus Wall Callcott and John Linnell, reflecting the interconnected nature of the RA community.

Patronage and Recognition

During his lifetime, Collins achieved significant recognition and attracted prestigious patronage. His appealing subject matter and polished technique found favour with collectors and the public alike. King George IV acquired his work, as did prominent figures like the Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, a noted art collector. His paintings were sought after, reproduced as engravings, and widely admired for their charm, technical skill, and perceived moral wholesomeness.

His election as a full Royal Academician in 1820 confirmed his status within the artistic elite. The subsequent appointment as RA Librarian further underscored the respect he commanded among his peers. His works consistently featured in major exhibitions, contributing significantly to the character of British art during the Regency and early Victorian periods. He successfully navigated the art market of his time, building a prosperous career based on his distinctive artistic vision.

Health, Final Years, and Legacy

Collins's later years were increasingly affected by ill health. He suffered from rheumatic fever, which likely contributed to the heart condition that would eventually prove fatal. These health problems forced him to resign from his position as RA Librarian in 1843, just three years after his appointment. Despite his ailments, he continued to paint, though perhaps with less vigour than before.

William Collins died in London on February 17, 1847, at the age of 59 (or possibly 60, depending on the exact birth date, though 1787 is now favoured by research). He was buried at the Cemetery of St. Mary, Paddington, near his home. His death was noted with respect in the art world, acknowledging the loss of a popular and accomplished painter. His son, Wilkie Collins, published a memoir of his father's life in 1848, helping to preserve his memory.

In the decades following his death, Collins's reputation experienced a gradual decline, particularly in comparison to the soaring posthumous fame of Constable and Turner. Changing artistic tastes, moving away from Victorian sentimentality towards greater realism or impressionistic approaches, led to his work being seen as somewhat dated by some later critics. His meticulous finish was sometimes described as 'dry' compared to the freer handling of others. Consequently, while represented in major public collections like the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate Britain, and the Royal Collection, he is not as widely celebrated today as some of his contemporaries.

However, a reassessment acknowledges William Collins's considerable achievements and his specific contribution to British art. He was a highly skilled painter who captured the coastal and rural life of his time with sensitivity and charm. His work provides valuable documentation of social customs, landscapes, and the prevailing aesthetic sensibilities of the early 19th century. He excelled in creating accessible, beautifully crafted images that resonated deeply with his audience, mastering the depiction of light, detail, and gentle human emotion. As a chronicler of the English seaside and countryside, and a master of the popular genre scene, William Collins remains an important and engaging figure in the history of British painting. His best works continue to delight viewers with their clarity, craftsmanship, and affectionate portrayal of a bygone era.