William Dyce (1806-1864) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. A native of Aberdeen, Scotland, Dyce was a man of diverse talents and profound intellect, navigating the complex currents of artistic, religious, and scientific thought that characterized the Victorian era. His career encompassed painting, design, and, crucially, art education, where his reforms left an indelible mark. Dyce’s artistic output, influenced by his deep engagement with early Italian Renaissance masters and his connections with the German Nazarene movement, often explored religious and historical themes with a distinctive blend of precision, spiritual depth, and intellectual rigor. He also played a vital, albeit nuanced, role in the orbit of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, acting as a bridge between older traditions and emerging artistic ideals.

Early Life and Formative Education

Born in Aberdeen on September 19, 1806, William Dyce was the son of Dr. William Dyce, a respected physician and lecturer in medicine at Marischal College, and Margaret Chalmers. His upbringing in a household that valued both scientific inquiry and intellectual pursuits undoubtedly shaped his broad range of interests. He received his early education at Aberdeen Grammar School before matriculating at Marischal College, University of Aberdeen, at a remarkably young age.

Dyce demonstrated considerable academic promise, graduating with a Master of Arts degree in 1824, when he was just sixteen. While his initial studies might have pointed towards a career in medicine or academia, following in his father's footsteps, his true passion lay in the arts. After completing his degree, he briefly attended the Royal Scottish Academy's schools in Edinburgh before making his way to London in 1825 to enroll in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. This formal training provided him with a foundational understanding of academic art principles, though his artistic vision would soon be expanded by experiences abroad.

Italian Sojourns and the Nazarene Influence

Dyce's artistic development was profoundly shaped by his visits to Italy. His first trip, undertaken around 1825-1826, and a subsequent, more extended stay from 1827 to 1828, exposed him to the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance. He immersed himself in the study of artists like Raphael, Perugino, and Fra Angelico, whose clarity of form, spiritual sincerity, and meticulous technique resonated deeply with him. This period was crucial in steering him away from the more flamboyant trends of contemporary British art towards a more austere and spiritually infused aesthetic.

During his time in Rome, Dyce came into contact with the Nazarene movement, a group of German Romantic painters who sought to revive the artistic principles and spiritual devotion they perceived in late medieval and early Renaissance art. Key figures in this group included Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Peter von Cornelius, and Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld. Dyce formed a particularly close association with Overbeck. The Nazarenes' emphasis on religious themes, their rejection of academic Mannerism, and their admiration for artists preceding Raphael left a lasting impression on Dyce. He absorbed their commitment to detailed execution, linear clarity, and the moral purpose of art, principles that would become hallmarks of his own work.

This engagement with both early Italian art and the contemporary Nazarene philosophy provided Dyce with a unique artistic vocabulary. He became one of the earliest British artists to truly understand and assimilate the principles of the Quattrocento, long before they became a more widespread interest in Britain, partly through the advocacy of figures like John Ruskin.

Return to Britain and Early Career

Upon his return to Britain, Dyce initially settled in Edinburgh, where he began to establish himself as a portrait painter. Portraiture provided a steady source of income, and he executed numerous likenesses with skill and sensitivity. However, his ambitions extended beyond this genre. His Italian experiences had instilled in him a desire to tackle more complex historical and religious subjects, informed by the gravitas and spiritual depth he admired in the Old Masters and the Nazarenes.

One of his early notable works from this period was Bacchus Nursed by the Nymphs of Nysa (though sometimes referred to as Bacchus nursing his Fawn), exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1828. While still reflecting some conventional academic training, it hinted at his evolving style. He also began to explore literary and mythological themes, gradually building a reputation for his thoughtful and meticulously crafted compositions.

His painting The Descent of Venus (c. 1827-1830s), with its classical subject matter treated with a certain coolness and precision, further showcased his developing style. Dyce was not content to merely imitate; he sought to synthesize his influences into a personal idiom. His early works demonstrated a careful attention to detail, a refined sense of color, and a preference for clearly articulated forms, setting him apart from many of his British contemporaries.

The Pre-Raphaelite Connection

William Dyce holds a significant, if somewhat elder-statesman-like, position in relation to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. While not a formal member of the PRB, Dyce was sympathetic to their aims and shared many of their artistic preoccupations, particularly their admiration for early Italian art, their commitment to truth to nature, and their desire for a more spiritually meaningful art.

Dyce's own work, with its emphasis on clear outlines, bright colors, and detailed rendering, anticipated some of the stylistic characteristics that would define Pre-Raphaelitism. He was already practicing a form of art that looked back to the period before Raphael, valuing sincerity and meticulousness over the generalized forms and dramatic effects favored by later academic traditions influenced by artists like Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Furthermore, Dyce played a direct role in supporting the young Pre-Raphaelites. He is credited with recognizing their talent and introducing them to the influential critic John Ruskin, whose subsequent championing of the PRB proved crucial to their public acceptance. Dyce's established position and his understanding of their artistic goals made him a valuable ally. He admired their earnestness and their rebellion against the tired conventions of the Royal Academy, even if his own approach was often more reserved and scholarly.

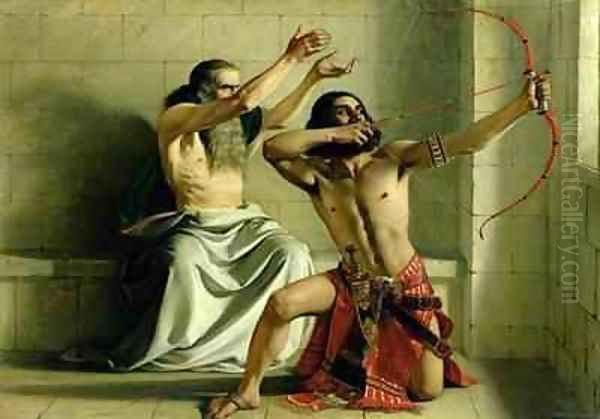

Works like Dyce's Joash Shooting the Arrow of Deliverance (1844) and The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel (1850, exhibited 1853) demonstrate stylistic and thematic affinities with Pre-Raphaelite concerns, showcasing biblical narratives with a focus on emotional sincerity and detailed naturalism. However, Dyce's art generally maintained a greater degree of classical composure and was less overtly radical in its departure from academic norms than the more confrontational works of the younger PRB members. He was a precursor and a fellow traveler rather than a core member of the movement.

Major Commissions and Public Works

A significant portion of William Dyce's career was dedicated to large-scale public commissions, most notably the frescoes for the newly rebuilt Houses of Parliament at Westminster. This ambitious project, overseen by a Royal Commission that included figures like Charles Lock Eastlake, aimed to adorn the new seat of British government with art that celebrated national history and values. Dyce was selected to contribute several major works, a testament to his growing reputation and his perceived suitability for such monumental undertakings.

His most famous frescoes are located in the Queen's Robing Room, depicting scenes from the legends of King Arthur. These include The Admission of Sir Tristram to the Fellowship of the Round Table and Piety: The Departure of the Knights of the Round Table on the Quest for the Holy Grail. The Arthurian cycle was intended to embody virtues such as chivalry, justice, and religion. Dyce approached these subjects with his characteristic seriousness and meticulous attention to historical detail, drawing on medieval sources and employing a style that blended Renaissance clarity with a certain Gothic sensibility.

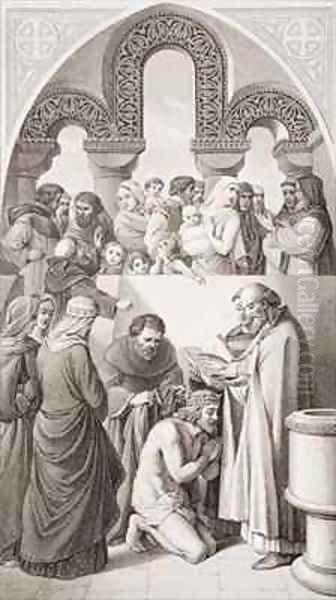

Another important commission at Westminster was The Baptism of Ethelbert (completed 1846) in the House of Lords. This work, depicting the conversion of the Anglo-Saxon king to Christianity, was praised for its dignified composition and its harmonious integration with the architectural setting. Dyce's experience with fresco painting, a technique he had studied in Italy and which was being revived in Britain at the time, made him well-suited for these demanding projects. Other artists like Daniel Maclise also contributed significantly to the Parliament decorations.

These public commissions were arduous and time-consuming. Dyce faced numerous challenges, including technical difficulties with the fresco medium in the British climate and the complexities of working within a large bureaucratic framework. The Arthurian series, in particular, remained unfinished at the time of his death, partly due to his declining health and the immense labor involved. Nevertheless, these works stand as important examples of Victorian history painting and demonstrate Dyce's commitment to creating art of national significance.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

William Dyce's artistic style is characterized by a unique synthesis of influences. His deep admiration for early Italian Renaissance masters like Fra Angelico and Perugino is evident in the clarity of his compositions, the purity of his color palette, and the spiritual intensity of his figures. This was further reinforced by his contact with the Nazarenes, particularly Overbeck, who encouraged a return to the perceived sincerity and piety of pre-High Renaissance art.

Dyce's paintings often exhibit a meticulous attention to detail, a quality he shared with the Pre-Raphaelites. This is particularly apparent in his landscape paintings, such as the celebrated Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858 (exhibited 1860). This work is a marvel of detailed observation, depicting the geological formations of the coastline with scientific accuracy, and even includes Donati's Comet in the sky. The figures of his family members collecting shells add a personal, poignant touch to this scientifically informed landscape. The painting was, however, criticized by some contemporaries for being "too real," highlighting the tension between emerging naturalism and established picturesque conventions.

Religious themes were central to Dyce's oeuvre. Works like The Virgin Mother (also known as Madonna and Child), Christabel (inspired by Coleridge's poem), and The Man of Sorrows (c. 1860) reveal his profound engagement with Christian iconography and narrative. The Man of Sorrows, depicting Christ seated in a desolate, rocky landscape, is particularly striking for its stark emotional power and its almost geological rendering of the setting, reflecting Dyce's interest in the natural sciences.

While often associated with religious and historical subjects, Dyce also produced sensitive portraits and genre scenes. His style, though evolving, consistently maintained a high level of craftsmanship, intellectual rigor, and a quest for spiritual or moral significance. He was less interested in the overtly sentimental or anecdotal than many of his Victorian peers, preferring subjects that allowed for a more profound and contemplative treatment. His work often has a certain coolness or reserve, a quality that perhaps stemmed from his scholarly temperament and his affinity for the restrained dignity of early Renaissance art. He was also influenced by the High Renaissance masters like Titian and the classical compositions of Nicolas Poussin, which tempered the more archaic elements derived from earlier sources.

Role as an Educator and Reformer

Beyond his achievements as a painter, William Dyce made a profound and lasting contribution to art education in Britain. He was a thoughtful and progressive figure who recognized the need for reform in the way art and design were taught. In 1837, he was appointed Superintendent of the School of Design in Edinburgh, and his report on continental design schools, particularly those in France and Germany, led to his appointment in 1840 as Director of the newly established Government School of Design in London, which later evolved into the Royal College of Art.

Dyce was instrumental in shaping the curriculum and philosophy of this institution. He advocated for a more systematic and practical approach to design education, emphasizing the importance of drawing from nature, understanding historical styles, and applying artistic principles to industrial manufactures. He believed that good design was essential for improving the quality of British goods and enhancing the nation's competitiveness. His efforts laid the groundwork for what became known as the "South Kensington System," a national system of art education that influenced generations of artists and designers.

He also held academic positions, including Professor of the Theory of the Fine Arts at King's College London from 1844. His lectures and writings, such as "The Theory of the Fine Arts," demonstrated his scholarly approach to art history and aesthetics. Dyce was a firm believer in the intellectual underpinnings of artistic practice and sought to elevate the status of art education.

His commitment to education extended to church music. Dyce was a knowledgeable musician and a proponent of reforms in Anglican liturgical music, advocating for a return to earlier, more austere forms of plainsong and polyphony, aligning with the High Church sympathies of the Oxford Movement. He published a significant edition of the Book of Common Prayer with plainchant notation. This multifaceted engagement with different forms of cultural and educational reform highlights the breadth of his intellect and his desire to contribute to the cultural life of his time.

Scientific and Other Interests

William Dyce was a man of remarkably diverse intellectual pursuits, a true Victorian polymath whose interests extended well beyond the confines of painting and art education. His early upbringing in a physician's household and his own scientific aptitude fostered a lifelong engagement with various scientific disciplines. This is most famously reflected in his painting Pegwell Bay, which meticulously records geological strata and an astronomical event, Donati's Comet.

His interest in geology is also evident in the stark, rocky landscapes that feature in some of his religious paintings, such as The Man of Sorrows. These settings are not merely picturesque backdrops but seem to be rendered with an understanding of geological formations, adding another layer of meaning and realism to his work.

Dyce also wrote on subjects seemingly far removed from art, including a pamphlet on "animal magnetism" (mesmerism), a topic of considerable debate and fascination in the 19th century. This indicates his willingness to explore unconventional areas of knowledge and his engagement with contemporary scientific and pseudo-scientific discussions.

Furthermore, Dyce was among the early artists to recognize the potential of photography as an aid to painting. While not a photographer himself in a professional sense, he understood its utility for capturing detail and likeness, and he is known to have used photographic studies in the preparation of some of his works. This forward-thinking approach places him among those artists who were quick to explore the implications of new technologies for artistic practice. His wide-ranging intellect also led him to be a founder of the Motett Society, dedicated to the revival of early church music, further underscoring his scholarly and reformist zeal across multiple domains.

Later Years, Legacy, and Academic Evaluation

The later years of William Dyce's life were increasingly burdened by ill health and the immense pressures of his public commissions, particularly the ongoing work on the Houses of Parliament frescoes. The demands of these large-scale projects, coupled with his meticulous working methods, took a toll on his physical well-being. He passed away in Streatham, London, on February 14, 1864, leaving some of his major works, including the Arthurian cycle, incomplete. He was buried at St Leonard's Church, Streatham.

In the immediate aftermath of his death, Dyce's reputation, like that of many Victorian artists, underwent a period of relative neglect as artistic tastes shifted. However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a significant reassessment of his contributions. Art historians now recognize him as a pivotal figure who bridged various artistic currents: the academic tradition, the influence of the Nazarenes, the burgeoning Pre-Raphaelite movement, and the drive for art education reform.

Academics highlight his role as an important precursor to the Pre-Raphaelites, both stylistically and in his advocacy for early Italian art. His intellectual depth and the scholarly rigor he brought to his work are widely acknowledged. Works like Pegwell Bay and The Man of Sorrows are now considered masterpieces of Victorian art, admired for their technical skill, emotional intensity, and complex layering of meaning. His influence on art education through the South Kensington System was profound and long-lasting, shaping design training in Britain for decades.

Modern scholarship also appreciates Dyce's interdisciplinary nature. His engagement with science, music, and theology enriches the understanding of his artistic output. Exhibitions and publications have brought his work to a wider audience, securing his place as a highly original and influential artist whose contributions were crucial to the development of British art in the 19th century. He is remembered not only for his paintings but also for his intellectual vision and his commitment to the cultural and educational advancement of his society. His legacy is particularly strong in his native Scotland, where institutions like the National Galleries of Scotland hold significant examples of his work, and in the broader history of Victorian art where his unique blend of influences, including artists like David Scott (a Scottish contemporary, though of a different artistic temperament), marks him as a distinctive voice.

Conclusion

William Dyce was a complex and multifaceted artist whose career traversed the dynamic landscape of 19th-century British art and culture. From his early immersion in the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance and his formative encounters with the German Nazarenes, to his influential role in art education and his nuanced relationship with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Dyce forged a distinctive artistic path. His paintings, characterized by meticulous craftsmanship, intellectual depth, and a profound spiritual sensibility, tackled grand historical and religious themes with a unique blend of precision and gravitas.

As an educator, his reforms had a lasting impact on the teaching of art and design in Britain. As an intellectual, his interests spanned science, music, and theology, reflecting the broad curiosity of a Victorian polymath. While perhaps not achieving the widespread fame of some of his contemporaries during his lifetime or in the decades immediately following, William Dyce's contributions are now increasingly recognized. He stands as a crucial figure in understanding the artistic and intellectual currents of the Victorian era, an artist whose thoughtful and deeply considered work continues to resonate with its blend of aesthetic refinement and profound thematic engagement.