Thomas Pollock Anshutz (October 5, 1851 – June 16, 1912) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of American art, not only for his compelling contributions as a painter but also for his profound and lasting influence as an educator. His career bridged the staunch Realism of his mentor, Thomas Eakins, and the burgeoning modern art movements of the early 20th century, many of whose proponents were his students. Anshutz's dedication to anatomical accuracy, keen observation, and a nuanced understanding of color and light shaped his artistic output and his pedagogical approach, leaving an indelible mark on generations of American artists.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Newport, Kentucky, on October 5, 1851, Thomas Anshutz's early life provided little overt indication of his future artistic prominence. His family environment was not one steeped in the arts, yet an innate inclination towards visual expression must have been present. The pivotal moment in his early artistic journey occurred in 1875 when he made the decision to move to Philadelphia. This city, a burgeoning cultural and artistic hub in post-Civil War America, would become the crucible for his development.

Upon arriving in Philadelphia, Anshutz initially enrolled at the National Academy of Design, seeking foundational training. However, his most formative educational experience began shortly thereafter when he entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). It was here that he came under the tutelage of the formidable Thomas Eakins, a master of American Realism whose rigorous teaching methods and uncompromising artistic vision would profoundly shape Anshutz. Eakins's emphasis on direct observation, the study of anatomy (including dissections), and the use of photography as an artistic tool were revolutionary for the time and became cornerstones of Anshutz's own artistic and teaching philosophy.

Under the Wing of Eakins: A Formative Apprenticeship

The relationship between Thomas Eakins and Thomas Anshutz was one of mentor and devoted protégé. Anshutz quickly distinguished himself as one of Eakins's most talented and dedicated students. He absorbed Eakins's principles, particularly the importance of understanding the human form from the inside out. This involved not just life drawing but also attending anatomical lectures and participating in dissections, practices Eakins championed for artists.

Anshutz's diligence and talent did not go unnoticed. He became Eakins's assistant, aiding him in his teaching and artistic endeavors. This close association provided Anshutz with invaluable insights into Eakins's working methods and artistic philosophy. He assisted Eakins with photographic studies, which Eakins used extensively for anatomical reference and compositional planning. This early exposure to photography as an aid to painting would inform Anshutz's own work and teaching later in his career. The influence was reciprocal to some extent; Anshutz's own keen eye and steady hand were assets to Eakins.

A Distinguished Career at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Following Eakins's controversial dismissal from PAFA in 1886 (largely due to his insistence on using fully nude models in mixed-gender classes), Anshutz, despite his loyalty to his mentor, stepped into a more prominent teaching role at the institution. He would remain a central figure at PAFA for the majority of his career, eventually holding the esteemed positions of Chief Demonstrator of Anatomy and later, Chief of Drawing and Painting. His tenure at the Academy spanned over three decades, until his retirement due to ill health in 1911.

As an instructor, Anshutz carried forward many of Eakins's core tenets, particularly the emphasis on anatomical understanding and rigorous drawing. However, his teaching style was generally considered less dogmatic and perhaps more encouraging of individual expression than Eakins's. He fostered an environment where students were grounded in strong technical skills but also urged to explore their own artistic voices. Anshutz was known for his thoughtful critiques and his ability to guide students without imposing his own style too heavily. He understood the importance of a solid foundation but also recognized the evolving landscape of art.

Nurturing a Generation: Anshutz's Students and Their Impact

Thomas Anshutz's most enduring legacy might well be the remarkable cohort of artists he taught and mentored at PAFA. Many of these students went on to become leading figures in American art, shaping the course of various movements. Among his most notable pupils were Robert Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, George Luks, and Everett Shinn, who collectively formed the core of the Ashcan School. This group, inspired by Henri's call to paint contemporary urban life with unvarnished realism, owed a debt to Anshutz's grounding in observational painting, even as they diverged in subject matter and approach.

Robert Henri, in particular, became an influential teacher himself, carrying forward a spirit of artistic independence that Anshutz had helped foster. John Sloan, known for his gritty depictions of New York City life, and William Glackens, whose work often featured a lighter, more Impressionistic touch, also benefited from Anshutz's instruction. Other significant artists who studied with Anshutz include Charles Demuth, a key figure in Precisionism; Charles Sheeler, another pioneer of Precisionism who also excelled in photography; John Marin, known for his modernist watercolors; and Arthur B. Carles, an early American modernist. The sheer diversity of styles pursued by his students attests to Anshutz's ability to impart fundamental skills while encouraging individual exploration. His classroom was a fertile ground for the next wave of American artists, including figures like Cecilia Beaux, who, though more a contemporary, interacted with the PAFA environment Anshutz shaped.

Anshutz's Artistic Vision: Realism, Color, and Light

Thomas Anshutz's own artistic output, while perhaps overshadowed by his teaching legacy, is significant in its own right. His style is primarily rooted in Realism, a direct inheritance from Eakins, characterized by meticulous draftsmanship, careful attention to anatomical accuracy, and a commitment to depicting subjects with honesty and directness. His portraits, for instance, often convey a strong sense of the sitter's character, eschewing flattery for a more penetrating psychological insight.

However, Anshutz was not merely an Eakins imitator. Over time, his palette brightened, and he showed an increasing interest in the effects of light and color, sometimes incorporating elements that bordered on Impressionism, particularly in his landscapes and genre scenes. He was a keen observer of the interplay of light on surfaces and explored a richer chromatic range than was typical of Eakins's more somber tones. This exploration of color became a significant aspect of his later teaching, encouraging students to experiment with brighter palettes. His involvement with the Darby School, which he co-founded, further reflects this interest in plein air painting and capturing the fleeting effects of natural light, aligning with some Impressionist concerns.

Anshutz also continued to utilize photography as a tool, not as a replacement for observation but as an aid for capturing poses, details, and compositional ideas. His genre scenes often depict everyday life, from domestic interiors to outdoor activities, rendered with a quiet dignity and a focus on the human element.

Landmark Compositions: Exploring American Life

Several of Anshutz's paintings stand out as key works in his oeuvre and in the broader context of American art.

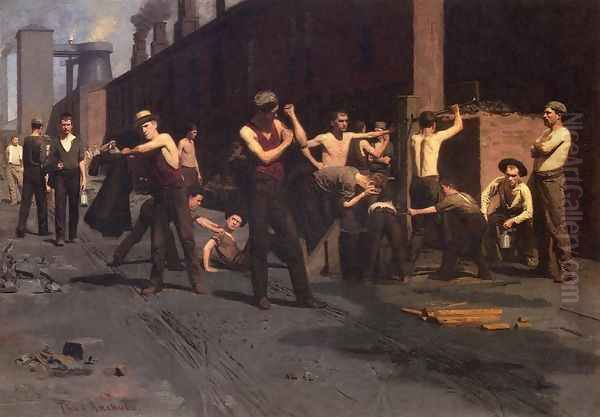

The Ironworkers' Noontime (originally titled The Ironworkers' Nooning, c. 1880-1881) is arguably his most famous painting. Created relatively early in his career, this work depicts a group of foundry workers taking their midday break in the factory yard in Wheeling, West Virginia. The figures are rendered with a powerful, almost sculptural solidity, showcasing Anshutz's mastery of anatomy and his ability to capture individual character even within a group scene. The painting is a significant document of American industrial life, though it tends to focus on the humanity and dignity of the workers rather than offering overt social critique. Its composition is carefully structured, and the play of light on the figures' bodies and the industrial setting is masterfully handled. It remains a cornerstone of American Realist painting.

A Rose (1907) is another of Anshutz's celebrated works, a portrait that exemplifies his mature style. The painting depicts Rebecca H. Whelen, the daughter of a PAFA trustee and one of Anshutz's frequent models. She is shown in a thoughtful, introspective pose, dressed in a vibrant pink gown, holding a rose. The work is notable for its rich color, elegant composition, and the psychological depth conveyed in the sitter's expression. Anshutz described the subject as representing "a type of American woman, a lady," and the painting explores themes of femininity, beauty, and quiet contemplation. While rooted in Realist observation, the painting also showcases Anshutz's sophisticated use of color and his ability to create an evocative mood. It reflects the late 19th-century interest in depicting refined womanhood, yet with a modern sensibility that captures her intellect and emotional alertness.

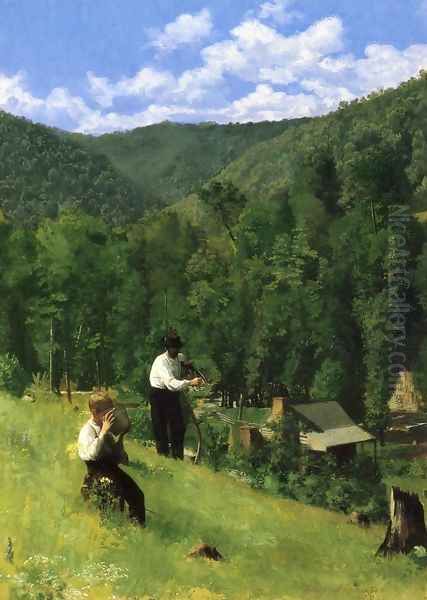

Other notable works include The Farmer and His Son at Harvesting (1879), an earlier genre scene showing his Eakins-influenced realism, and numerous portraits such as Portrait of the Artist's Wife (1906) and Portrait of Mrs. Anshutz, which demonstrate his skill in capturing likeness and personality. His genre scenes like Checker Players reveal his interest in everyday activities and human interaction, rendered with keen observation. Works like The Woman in Red showcase his evolving use of color and his ability to create striking visual statements.

European Sojourn and the Darby School

In 1892, Anshutz married Effie Shriver Russell and the couple embarked on a honeymoon to Paris. This trip also served as an opportunity for Anshutz to further his artistic studies. In Paris, he enrolled at the Académie Julian, where he studied with renowned academic painters such as Henri Lucien Doucet and William-Adolphe Bouguereau. While the highly polished, idealized style of academic masters like Bouguereau was quite different from Anshutz's Eakins-derived Realism, this European exposure likely broadened his technical knowledge and exposed him to different artistic currents. He would have also encountered the full force of French Impressionism, which may have reinforced his own explorations of light and color.

Upon his return to Philadelphia in 1893, Anshutz resumed his teaching at PAFA. Around this time, he also became involved with the Darby Summer School of Painting in Darby, Pennsylvania, which he co-founded with Hugh Breckenridge. The Darby School emphasized plein air painting, encouraging artists to work directly from nature and to capture the effects of light and atmosphere. This venture reflected Anshutz's growing interest in landscape painting and a more Impressionistic approach to color and light, providing an alternative or supplement to the more studio-based, figure-focused instruction at PAFA. This initiative shows his adaptability and his willingness to embrace evolving artistic ideas, even while maintaining his core Realist principles.

Later Years and Lasting Impact

Thomas Anshutz continued to teach and paint with dedication throughout the remainder of his career. He was a respected figure in the Philadelphia art world, known for his integrity, his skill as an artist, and his profound impact as an educator. His influence extended beyond his direct students; he helped to create an environment at PAFA that was both rigorous and open to new ideas, fostering a critical period of transition in American art. He was a bridge figure, connecting the 19th-century Realist tradition of Eakins and Winslow Homer to the more experimental art of the early 20th century, as practiced by his students who went on to form movements like the Ashcan School or explore early Modernism.

His students, including Robert Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, Charles Sheeler, John Marin, and Arthur B. Carles, carried his lessons in various directions, but the common thread was often a strong foundation in drawing and a commitment to personal vision, qualities Anshutz championed. Even artists who pursued vastly different styles, such as the Impressionist Mary Cassatt or the portraitist Cecilia Beaux, were part of the broader artistic milieu that Anshutz contributed to, particularly through his long association with PAFA. His contemporaries, like John Singer Sargent and James Abbott McNeill Whistler, represented other facets of the rich artistic tapestry of the era, with Whistler's emphasis on color harmony perhaps finding an echo in Anshutz's later chromatic explorations.

In 1909, Anshutz was made head of the painting department at PAFA. However, his health began to decline, and he was forced to retire from his teaching duties in 1911. Thomas Pollock Anshutz passed away on June 16, 1912, in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, leaving behind a significant body of work and an even more substantial legacy as one of America's most influential art educators.

Conclusion: A Quiet Force in American Art

Thomas Pollock Anshutz may not possess the same level of household-name recognition as his mentor, Thomas Eakins, or some of his more famous students like Robert Henri. Yet, his contributions to American art are undeniable and deeply significant. As an artist, he produced compelling works of Realism that captured aspects of American life with honesty and skill, evolving to embrace a richer understanding of color and light. His paintings, particularly The Ironworkers' Noontime and A Rose, remain important examples of American painting from the period.

As an educator, his impact was monumental. For over thirty years at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, he shaped the development of countless artists, providing them with a strong technical foundation while encouraging their individual artistic journeys. He served as a crucial link between the 19th-century Realist tradition and the diverse artistic expressions of the 20th century. Thomas Anshutz was a quiet force, whose dedication, skill, and insightful teaching helped to define a pivotal era in American art history, ensuring his influence would be felt for generations to come.