Xu Beihong stands as a colossus in the landscape of 20th-century Chinese art. Revered as one of the founding figures of modern Chinese painting, often hailed as the "Father of Modern Chinese Painting," his life and work represent a dynamic synthesis of Eastern traditions and Western techniques. Born Xu Shoukang in 1895 in Yixing, Jiangsu province, into a time of immense social and cultural upheaval, he dedicated his life to the rejuvenation of Chinese art through realism and a profound engagement with both his heritage and global artistic currents. His journey took him from a humble rural background to the art academies of Europe and back, ultimately shaping the direction of art education and creation in China for generations.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Xu Beihong's artistic journey began under the tutelage of his father, Xu Dazhang, a self-taught painter and poet. Growing up in relative poverty, the young Xu learned the fundamentals of traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy, skills that would form the bedrock of his later innovations. The family's financial struggles were a constant reality, forcing Xu Beihong to seek opportunities beyond his rural hometown.

At the tender age of 15, he ventured to Shanghai, a bustling metropolis brimming with both opportunity and hardship. To support himself, he took on various commercial art jobs, creating illustrations and advertisements. This early exposure to the demands of commercial art, while born of necessity, likely honed his drafting skills and instilled a practical understanding of visual communication. Despite the challenges, his determination to pursue a serious artistic career never wavered.

Formative Years in Europe: Embracing Realism

A pivotal moment arrived around 1919 when Xu Beihong secured a government scholarship to study art in France. This marked the beginning of a transformative period abroad. He enrolled in the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, studying under prominent academic painters like Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret and Fernand Cormon (though the provided text mentions Flameng, Cormon and Dagnan-Bouveret were also key figures he encountered or studied under). He immersed himself in the rigorous training of the French academic tradition, focusing intently on mastering life drawing, anatomy, and oil painting techniques.

His time in Europe was not confined to Paris. Xu Beihong traveled extensively, visiting museums and galleries across the continent. He was particularly captivated by the masterpieces of the European Renaissance and the subsequent realist traditions. He spent countless hours in institutions like the Louvre, sketching and copying works by masters such as Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael. This deep engagement with Western classical and realist art convinced him that the path to revitalizing Chinese art lay in adopting these principles of direct observation, accurate representation, and scientific understanding of form and structure.

Life in Europe was far from easy. Financial difficulties were a constant companion, especially when government funding became unreliable. However, Xu found crucial support from figures like Zhao Songnan, the Chinese Consul General in Paris, and later through the patronage of Singaporean brothers Huang Mengkui and Huang Manshi, who recognized his talent and dedication. He also faced societal challenges, including instances of prejudice from some foreign students. Xu met these challenges with resilience, defending the dignity of his nation and earning respect through his exceptional talent and unwavering work ethic. This period also saw the complexities of his personal life unfold, particularly his relationship with Jiang Biwei, who had accompanied him abroad.

Return to China and Educational Leadership

Xu Beihong returned to China in 1927, armed with a mastery of Western techniques and a fervent mission to reform Chinese art. He quickly established himself as a leading figure in the art world and a passionate educator. He accepted a position at the National Central University in Nanjing (now Nanjing University), where he served as a professor in the art department.

His educational philosophy was revolutionary for its time. He championed the integration of rigorous, Western-style academic training – particularly emphasizing sketching from life – into the traditional Chinese art curriculum. He believed that the perceived decline in Chinese painting stemmed from a departure from direct observation and a reliance on copying past masters without genuine understanding. He advocated for "inheriting the ancient methods while innovating," urging artists to ground their work in realism and scientific principles while retaining the spirit of Chinese aesthetics.

His influence grew significantly, and he became a central figure in shaping the future of art education in China. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, his stature was further recognized when he was appointed the first president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing in 1950, a position he held until his death. Through his teaching and leadership, he trained and inspired countless students, many of whom became prominent artists themselves, including figures like Wu Guanzhong and Li Keran.

Artistic Style and Philosophy: A Synthesis of Cultures

Xu Beihong's unique artistic style is characterized by its masterful fusion of Chinese and Western elements. He sought to break away from what he saw as the overly stylized and repetitive nature of late traditional literati painting. His solution was not to abandon Chinese tradition entirely but to reinvigorate it with the structural rigor and observational accuracy of Western realism.

In his ink paintings, particularly his famous depictions of horses, he combined the expressive, fluid brushwork (xieyi) characteristic of traditional Chinese art with a deep understanding of animal anatomy derived from his Western training. His horses are not mere symbols; they are vibrant, dynamic creatures, captured with anatomical precision yet imbued with a powerful sense of spirit and movement. He used ink and wash with masterful control, achieving effects of volume, muscle tension, and energy that were unprecedented.

In his oil paintings, Xu embraced the techniques of European realism and classicism. He focused on accurate drawing, solid modeling of form, and a realistic depiction of light and shadow. However, his subject matter often remained deeply rooted in Chinese history, mythology, and contemporary life. He aimed to create art that was both technically proficient in a Western sense and spiritually resonant within a Chinese cultural context. His commitment to realism was not merely aesthetic; it was deeply tied to his belief in art's social function – its ability to reflect reality, inspire patriotism, and contribute to national progress. This stance often put him in contrast with other modern Chinese artists like Lin Fengmian or Liu Haisu, who were more influenced by Post-Impressionism and Fauvism.

Masterpieces and Major Themes

Xu Beihong's oeuvre is vast and varied, encompassing ink painting, oil painting, drawing, and calligraphy. Several works stand out as iconic representations of his artistic vision and patriotic spirit.

Galloping Horse(s) : Perhaps his most famous subject, Xu's horses became symbols of dynamism, freedom, and the unyielding spirit of the Chinese nation, especially during times of hardship like the Anti-Japanese War. He painted countless variations, each showcasing his unique blend of anatomical accuracy and expressive ink work. These works remain immensely popular and are considered emblematic of modern Chinese painting.

Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers : This large-scale oil painting, completed in 1930, depicts a historical tale of loyalty and sacrifice from the Han Dynasty. Tian Heng and his followers chose mass suicide over surrendering to the new emperor. Xu used this historical narrative to evoke themes of integrity, patriotism, and defiance, rendered with dramatic composition and realistic figuration influenced by European history painting.

The Foolish Old Man Who Removed the Mountains : Completed in 1940 during the height of the Anti-Japanese War, this monumental work (existing in both Chinese ink and oil versions) draws inspiration from an ancient Chinese fable. The story of the old man determined to move two mountains symbolizes perseverance, collective effort, and unwavering resolve in the face of overwhelming obstacles. Xu explicitly intended it as an allegory for China's resistance against Japanese aggression. The figures, depicted with powerful, muscular bodies, reflect his study of Western anatomy and his admiration for the strength of the common people. His time in India, where he met Mahatma Gandhi, also influenced the work, infusing it with a sense of shared struggle and resilience.

Jiufang Gao : This work, often depicting a legendary horse connoisseur recognizing a steed's true quality regardless of its appearance, reflects themes of discerning inner worth over superficiality, a subject close to Xu's heart as he championed unrecognized talents like Qi Baishi.

Wounded Lion : Painted during the war, this allegorical work depicts a lion, symbolizing China, injured but still defiant, conveying a message of resilience and unbroken spirit despite suffering.

Other significant works include historical and allegorical paintings like Hymn to the Fallen , contemporary scenes like Second Battle of Changsha , and numerous portraits, such as his sensitive portrayal of the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore. Across these diverse subjects, his commitment to realism and his deep engagement with China's past and present struggles remained constant.

Relationships with Contemporaries: Camaraderie and Debate

Xu Beihong moved within a vibrant circle of artists and intellectuals, engaging in both supportive friendships and spirited debates. His relationships with two giants of modern Chinese art, Qi Baishi and Zhang Daqian, are particularly noteworthy.

He met the considerably older Qi Baishi in 1928. Despite the age gap and Qi's roots in traditional folk art, Xu deeply admired Qi's originality and artistic power. At a time when Qi's work was not fully appreciated by the academic establishment, Xu championed him, famously inviting him to teach at the Beiping University Art College and providing personal and financial assistance. Qi Baishi, in turn, held Xu in high regard, referring to him as a true "confidant" and "benefactor" , expressing his gratitude through gifts of paintings and calligraphy. Their mutual respect transcended stylistic differences, highlighting Xu's broad appreciation for genuine artistic talent.

His friendship with Zhang Daqian began in the early 1930s. They shared mutual respect and occasionally collaborated on paintings, such as Lotus and Shrimp . Xu recognized Zhang's prodigious talent and actively promoted his work, helping him gain international exposure. Zhang Daqian famously praised Xu, adapting his own name to declare Xu "the one great master in 500 years" . They often gathered to paint and discuss art, embodying a spirit of artistic exchange.

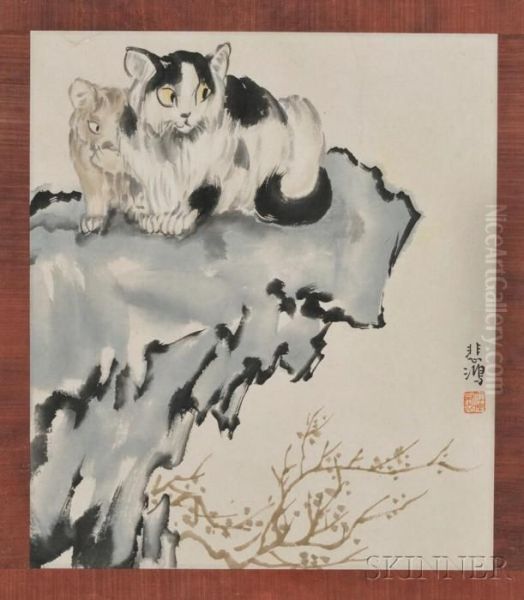

Beyond these close friendships, Xu interacted with many other key figures. He engaged in public debate with the poet Xu Zhimo over artistic styles following the first National Art Exhibition in 1929, a disagreement Xu later commemorated with a touch of humor in his painting Cat . His connections extended indirectly to figures like Lin Huiyin through their shared social circles and encounters with international figures like Rabindranath Tagore, whom Xu painted. He also knew and interacted with other major artists of his time, such as Pan Tianshou and Fu Baoshi , even if their artistic philosophies sometimes diverged from his strong emphasis on realism.

Art for National Salvation: The Anti-Japanese War Period

The outbreak of the full-scale Anti-Japanese War in 1937 profoundly impacted Xu Beihong. He dedicated his art and energy to the cause of national salvation, embodying the spirit of "art as a weapon." He believed artists had a crucial role to play in bolstering morale, raising awareness, and supporting the war effort.

He created numerous works directly addressing the conflict and celebrating Chinese resilience, including The Foolish Old Man Who Removed the Mountains, Wounded Lion, Hymn to the Fallen, and paintings depicting specific battles like the Second Battle of Changsha. His famous horse paintings from this era took on heightened symbolic meaning, representing the nation's untamed spirit galloping towards victory.

Beyond creating inspirational art, Xu Beihong actively engaged in fundraising. He traveled extensively, particularly in Southeast Asia (Nanyang), holding charity exhibitions in cities like Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, and Penang, as well as in India. He tirelessly exhibited his works, donating the entire proceeds to refugee relief funds and supporting the families of fallen soldiers. His efforts in Nanyang were crucial in mobilizing support among overseas Chinese communities for the war effort back home. He also held similar fundraising exhibitions within China, in places like Kunming, Baoshan, and Dali in Yunnan province. Through lectures and personal appearances, he used his platform to advocate for resistance and national unity.

Personal Life and Controversies

Xu Beihong's personal life was marked by intense relationships and significant turmoil, most notably his marriage to Jiang Biwei . Their relationship began dramatically when Jiang, already engaged to someone else, eloped with Xu. They traveled together to Japan and then France, sharing the hardships and aspirations of his student years.

However, fundamental differences in personality and lifestyle eventually strained the marriage. Xu was consumed by his artistic mission, often living frugally, while Jiang reportedly desired a more comfortable and socially prominent life. The breaking point came with Xu Beihong's deep emotional involvement with one of his students, Sun Duoci . Jiang Biwei reacted with intense anger and bitterness, leading to irreconcilable conflict, including acts like defacing a painting Xu had made.

Despite attempts at reconciliation, the couple separated and eventually divorced formally in 1945. The divorce settlement was demanding for Xu, requiring him to provide Jiang with a significant sum of money, over one hundred of his paintings, and property for child support. Jiang Biwei later maintained a long-term relationship with the politician Zhang Daofan but never remarried. She published memoirs detailing her perspective on the marriage, contributing to the public narrative of their complex and often painful relationship. This saga reflects not only personal tragedy but also the clash between traditional expectations and emerging ideas about love and marriage during the Republican era.

Regarding other aspects of his personal life, the provided source materials indicate there is no evidence to support stories sometimes circulated about Xu Beihong adopting an abandoned infant who later became a painter. Such stories appear to be conflated with unrelated individuals.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Xu Beihong passed away suddenly from a cerebral hemorrhage in Beijing on September 26, 1953, at the age of 58. Despite his relatively short life, his impact on modern Chinese art was immense and continues to be felt today.

His most significant contribution lies in his successful synthesis of Chinese and Western artistic traditions. By championing realism and integrating rigorous academic training (especially sketching) into the Chinese art system, he fundamentally reshaped art education and practice. He provided a compelling alternative to both the perceived stagnation of late traditional painting and the wholesale adoption of Western modernism.

As an educator, particularly during his tenure as president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, he mentored generations of artists. His emphasis on realism became a dominant force in Chinese art for decades, particularly aligning with the social and political demands of the mid-20th century. Artists like Wu Guanzhong and Li Keran, though developing their own distinct styles, carried forward aspects of his dedication to drawing from life and engaging with Chinese realities.

His iconic paintings, especially the Galloping Horse series, The Foolish Old Man Who Removed the Mountains, and Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers, remain celebrated masterpieces, admired for their technical skill, emotional power, and patriotic spirit. He demonstrated that Chinese art could absorb and adapt foreign techniques without losing its cultural identity, creating a new visual language that was both modern and distinctly Chinese. Xu Beihong's legacy is that of a bridge-builder, a passionate reformer, a dedicated educator, and a patriotic artist whose work continues to inspire and resonate.