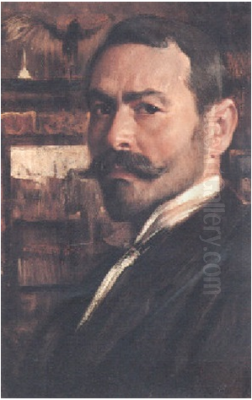

Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century European art. A Hungarian-born artist of Jewish heritage, he carved a distinct niche for himself with his monumental historical and mythological paintings, particularly those steeped in the grandeur and tragedy of ancient Rome. Operating primarily in Vienna and later Rome, Hirémy-Hirschl navigated a period of intense artistic change, adhering largely to academic traditions while imbuing his work with a profound sense of symbolism and often melancholic introspection that resonated with the fin-de-siècle mood. His art, though overshadowed for a time by the rise of modernism, continues to captivate with its technical brilliance, dramatic compositions, and evocative power.

Early Life and Viennese Foundations

Born Adolf Hirschl on January 31, 1860, in Temesvár, Hungary (now Timișoara, Romania), the artist's early life saw a move to Vienna. It was in this imperial capital, a vibrant hub of artistic and intellectual activity, that he would receive his formal training. He enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien), a bastion of academic tradition. Here, he studied from 1874 to 1882, honing his skills under the tutelage of influential painters.

Among his most significant teachers was Leopold Carl Müller, an Austrian genre painter known for his Orientalist scenes, who himself had been a student of the great historical painter Karl von Piloty in Munich. Müller's emphasis on meticulous detail and rich color palettes likely left an impression on the young Hirschl. Another prominent figure at the Academy during this period, though not a direct teacher in the same way, was August Eisenmenger, known for his historical and allegorical works, including frescoes for the Austrian Parliament Building. The prevailing artistic atmosphere in Vienna was also heavily influenced by the opulent and theatrical style of Hans Makart, whose grand historical and allegorical canvases dominated the Ringstrasse era. While Hirémy-Hirschl would develop his own distinct voice, the emphasis on historical subjects and technical mastery prevalent in Vienna undoubtedly shaped his early artistic ambitions.

His talent was recognized early. In 1878, he received a scholarship, and a pivotal moment came in 1882 when he was awarded the coveted Rome Prize (Preis von Rom) for his painting "Hannibal Crossing the Alps." This prestigious award, a testament to his burgeoning skill in historical painting, provided him with the means to travel and study in Rome, a destination that would prove profoundly influential for his artistic development and thematic preoccupations. It was during this period, or shortly thereafter, that he adopted the Magyarized surname Hirémy-Hirschl, perhaps to emphasize his Hungarian roots or to distinguish himself further.

The Roman Sojourn and Thematic Focus

The journey to Rome, funded by the prize, was transformative. Immersed in the remnants of classical antiquity, surrounded by the masterpieces of Renaissance and Baroque art, Hirémy-Hirschl found fertile ground for his imagination. The ancient world, with its epic narratives, dramatic figures, and enduring myths, became his primary wellspring of inspiration. He spent two years in Rome initially, from 1882 to 1884, and the city's atmosphere, its ruins, and its artistic treasures deeply permeated his consciousness.

Unlike some of his contemporaries who were beginning to explore impressionistic techniques or more avant-garde styles, Hirémy-Hirschl remained committed to a meticulously detailed, academic approach. His paintings from this period and throughout his career are characterized by their large scale, complex compositions, and a profound engagement with historical and mythological narratives. He was particularly drawn to themes of mortality, the afterlife, and the dramatic sweep of history, often tinged with a sense of impending doom or poignant reflection on lost glory. This focus on classical subjects aligned him with other European academic painters like the French Jean-Léon Gérôme or the British Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, though Hirémy-Hirschl’s interpretations often carried a more somber, psychological weight.

His time in Rome allowed him to study classical sculpture and architecture firsthand, informing the anatomical precision and historical accuracy he sought in his depictions. He became adept at rendering the human form, often in dynamic and emotionally charged poses, and at creating atmospheric settings that enhanced the narrative power of his chosen subjects. The city itself, a living museum, provided endless inspiration, and he would eventually make Rome his permanent home.

Masterworks of Myth and History

Hirémy-Hirschl's oeuvre is distinguished by several monumental canvases that showcase his technical virtuosity and his unique vision. Among his most celebrated works is "The Souls on the Banks of the Acheron" (1898). This vast, haunting painting depicts Hermes Psychopompos, the guide of souls, leading a throng of newly deceased spirits towards the ferryman Charon, who will transport them across the River Acheron into the underworld. The canvas is filled with a multitude of nude figures, each rendered with anatomical precision, their expressions conveying a range of emotions from fear and despair to resignation. The somber, ethereal lighting and the overwhelming sense of melancholy make this a powerful meditation on death and the afterlife, echoing the Symbolist preoccupations of artists like Arnold Böcklin, whose "Isle of the Dead" shares a similarly evocative and melancholic mood.

Another significant work is "Plague in Rome" (1884), painted during his initial Rome Prize period. This dramatic composition captures the horror and despair of a city gripped by pestilence, a theme with historical resonance that allowed Hirémy-Hirschl to explore intense human emotion and create a scene of epic tragedy. The dynamic grouping of figures and the palpable sense of suffering demonstrate his skill in historical narrative painting, a genre championed by artists like Karl von Piloty, whose influence was felt across Central Europe.

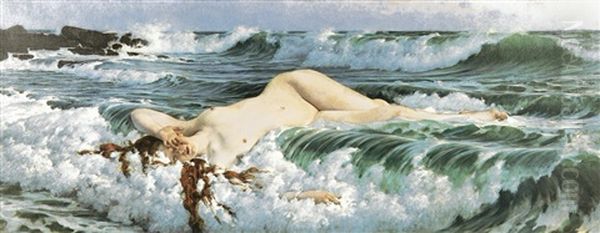

"The Birth of Venus," though the exact date is debated, is another key work that showcases his engagement with classical mythology. While the theme was famously depicted by Renaissance artists like Sandro Botticelli and later by academic painters such as Alexandre Cabanel, Hirémy-Hirschl’s interpretation would have brought his own particular sensibility to the subject, likely emphasizing both the idealized beauty of the goddess and perhaps a more introspective or dramatic rendering of the scene.

His painting "Sic Transit Gloria Mundi" (literally "Thus passes the worldly glory") further underscores his preoccupation with themes of transience and the fall of empires. This work, likely depicting a scene from Roman history, would have served as a memento mori, a reflection on the ephemeral nature of power and human achievement. Such themes were popular in academic art, allowing for grand historical reconstructions and moralizing undertones. Another work, "Vandals Invading Rome," would have similarly explored the dramatic decline of the Roman Empire, a subject rich in pathos and visual spectacle.

Beyond these large-scale oil paintings, Hirémy-Hirschl was also a proficient creator of watercolors and drawings, which often served as studies for his larger compositions or as standalone works. These pieces reveal his skill as a draftsman and his ability to capture light and form with sensitivity.

Artistic Style: A Blend of Academicism and Symbolist Sensibility

Hirémy-Hirschl’s artistic style is a complex amalgamation of influences and personal predilections. Fundamentally, he was an academic painter, deeply rooted in the traditions of the 19th-century European academies. This is evident in his meticulous draughtsmanship, his emphasis on anatomical correctness, his carefully constructed compositions, and his choice of historical and mythological subjects. His works demonstrate a thorough understanding of perspective, chiaroscuro, and the rendering of textures, all hallmarks of academic training. His approach can be compared to the polished classicism of artists like Frederic Leighton in England or William-Adolphe Bouguereau in France, who also excelled in mythological and historical scenes.

However, to label him solely as an academic painter would be to overlook the distinct Symbolist undercurrents in his work. Symbolism, which flourished in the late 19th century, sought to express ideas and emotions indirectly through symbolic imagery, often drawing on myth, dreams, and the imagination. Hirémy-Hirschl’s fascination with the afterlife, the mystical, and the psychologically charged moments of history aligns him with Symbolist tendencies. The ethereal, often somber, atmosphere of paintings like "The Souls on the Banks of the Acheron" transcends mere historical illustration, evoking a deeper, more universal contemplation of mortality. In this, his work finds parallels with European Symbolists such as Gustave Moreau in France or Franz von Stuck in Germany, who also explored mythological themes with a heightened sense of drama and psychological intensity.

His use of light is particularly noteworthy. He often employed dramatic lighting to heighten the emotional impact of his scenes, creating strong contrasts between illuminated figures and shadowy backgrounds. This not only added to the theatricality of his compositions but also served to emphasize the psychological state of his characters. His color palette, while capable of richness, often leaned towards more muted or somber tones, especially in his depictions of tragic or otherworldly subjects, contributing to the overall mood of his paintings.

While he embraced classical themes, his interpretation was not always purely Neoclassical in the stricter sense of artists like Jacques-Louis David. Instead, his classicism was often infused with a Romantic sensibility, emphasizing emotion, drama, and the sublime. He was a master storyteller in paint, capable of conveying complex narratives and evoking powerful emotional responses from the viewer.

The Viennese Art Scene and Shifting Tides

During his time in Vienna, Hirémy-Hirschl achieved considerable success and recognition. He was a respected figure in the city's art world, exhibiting his works and gaining accolades. However, the late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of significant artistic upheaval in Vienna. The established academic tradition, represented by the Association of Austrian Artists (Künstlerhaus), was being challenged by a younger generation of artists seeking new forms of expression.

This culminated in the formation of the Vienna Secession in 1897, led by Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Maria Olbrich, and Carl Moll, among others. The Secessionists broke away from the conservative Künstlerhaus, advocating for a broader definition of art, greater exposure to international modern art, and a closer integration of art and life (Gesamtkunstwerk). While Hirémy-Hirschl had an early acquaintance with Gustav Klimt, their artistic paths diverged significantly. Klimt and his circle embraced Art Nouveau, Symbolism with a distinctly modern, decorative, and often erotic charge, and a move away from traditional illusionistic painting.

Hirémy-Hirschl, with his commitment to large-scale historical and mythological painting executed in a more traditional academic style, found himself increasingly at odds with these new artistic currents. While his work contained Symbolist elements, its formal language remained rooted in the 19th-century academic tradition. The rise of the Vienna Secession and its progressive agenda gradually eclipsed the popularity of more traditional academic painters. It is noted that Hirémy-Hirschl did appear before Klimt's Secession foundation, indicating some level of interaction, but he was not a member and his artistic philosophy differed.

Personal Life and Departure from Vienna

A significant factor in Hirémy-Hirschl's later career and his relationship with Vienna was a personal scandal. He became involved with Isabella Henrietta Victoria Ruston (née justifyingly, a married woman of Austrian birth but identified as British). Their affair, and subsequent marriage after her divorce, caused a considerable stir in Viennese society. Sources suggest this marriage took place around 1898 or 1899. This controversial union, coupled perhaps with the shifting artistic climate in Vienna where his style was becoming less fashionable, likely contributed to his decision to leave the city.

He chose to settle permanently in Rome, a city that had always held a special allure for him and where his classically inspired art found a more consistently appreciative audience. In Rome, he could continue to immerse himself in the classical world that so fueled his art. He became an active member of the expatriate art community and participated in Roman art life, for instance, having connections with institutions like the Accademia di San Luca. He also reclaimed his Hungarian citizenship around this time, perhaps as part of this personal and professional transition.

Later Years in Rome and Continued Artistic Production

In Rome, Hirémy-Hirschl continued to paint, producing works that maintained his characteristic style and thematic concerns. He exhibited his art and remained a dedicated practitioner of his craft until his death. While the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, such as Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism, were revolutionizing the art world, Hirémy-Hirschl remained steadfast in his commitment to a more traditional, figurative, and narrative form of art.

His studio in Rome was reportedly filled with studies, sketches, and completed canvases, testament to his ongoing productivity. He focused on refining his depictions of the human form, exploring the nuances of classical mythology, and capturing the dramatic intensity of historical events. Even as artistic tastes evolved, he maintained a belief in the enduring power of classical themes and academic techniques.

Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl passed away in Rome on April 16, 1933, near the Schottenstift (Scottish Abbey), though his primary residence and place of death was Rome. He was buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome, a resting place for many foreign artists and intellectuals. Unfortunately, many of his major works were reportedly lost or their whereabouts became unknown after his death, particularly during the tumultuous period of World War II. However, a significant body of his work, including smaller paintings, watercolors, and drawings, was preserved by his heirs and has gradually come to light, allowing for a renewed appreciation of his talent.

Legacy and Rediscovery

For much of the 20th century, Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl, like many academic artists of his generation, was largely overlooked by art history, which tended to favor the narratives of modernist innovation. The grand historical and mythological paintings that had once been celebrated fell out of fashion, dismissed as overly theatrical or anachronistic. Artists like him were often seen as relics of a bygone era, unable or unwilling to engage with the radical changes transforming the art world.

However, in recent decades, there has been a significant reassessment of 19th-century academic art. Scholars and curators have begun to look beyond the modernist canon, recognizing the technical skill, intellectual depth, and cultural significance of artists who worked within academic traditions. Hirémy-Hirschl's work has benefited from this renewed interest. His paintings are now admired for their impressive scale, their meticulous execution, their dramatic power, and their unique blend of academic classicism and Symbolist introspection.

His ability to create vast, populated canvases filled with emotionally resonant figures, set within convincingly rendered historical or mythological landscapes, is undeniable. Works like "The Souls on the Banks of the Acheron" are recognized as masterpieces of late Symbolist art, comparable in their ambition and impact to the works of other European artists exploring similar themes. His art provides a valuable insight into the cultural preoccupations of the fin-de-siècle, a period marked by both a fascination with the past and an anxiety about the future.

Conclusion: An Artist of Enduring Fascination

Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl was an artist who bridged worlds: the waning traditions of 19th-century academicism and the burgeoning sensibilities of Symbolism; the imperial grandeur of Vienna and the timeless allure of Rome; the epic narratives of antiquity and the introspective mood of his own era. His commitment to historical and mythological subjects, rendered with consummate technical skill, produced works of enduring power and fascination. While his fame may have been eclipsed by the modernist movements that followed, his art offers a compelling vision, rich in drama, emotion, and a profound engagement with the human condition as seen through the lens of myth and history. As art history continues to broaden its perspectives, the contributions of artists like Hirémy-Hirschl are being increasingly recognized, securing his place as a significant and distinctive voice in the complex tapestry of European art at the turn of the twentieth century. His paintings invite viewers to contemplate the grand themes of life, death, and the enduring legacy of the classical world, rendered with a unique blend of academic rigor and melancholic poetry.