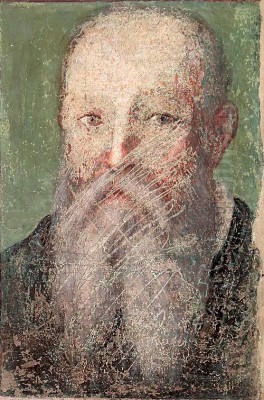

Agnolo di Cosimo, known to the world as Agnolo Bronzino, stands as one of the most significant figures of the Florentine High Renaissance and the ensuing Mannerist period. Born near Florence in Monticelli on November 17, 1503, he rose from relatively humble beginnings to become the preeminent court painter to the powerful Medici dynasty. His life spanned a period of immense artistic innovation and social change, and his work reflects both the refined aesthetics and the underlying tensions of his time. Bronzino passed away in his native Florence on November 23, 1572, leaving behind a legacy of exquisitely crafted portraits and complex allegorical paintings that continue to fascinate and intrigue viewers centuries later.

The nickname "Il Bronzino," meaning "the bronze one," is traditionally thought to refer either to his relatively dark complexion or perhaps the color of his hair. Regardless of its origin, the name became synonymous with a distinct artistic style characterized by cool elegance, meticulous detail, and a sense of detached sophistication. He was a central figure in the development and dissemination of Mannerism, a style that emerged after the High Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and the early Michelangelo, seeking new forms of expression that emphasized artifice, grace, and intellectual complexity over naturalism alone.

Early Life and Formative Training

Bronzino's artistic journey began under the tutelage of lesser-known painters, including Raffaellino del Garbo. However, the most decisive influence on his development was his apprenticeship with Jacopo da Pontormo, himself a leading figure of early Florentine Mannerism and a student of the great Andrea del Sarto. Bronzino entered Pontormo's workshop likely in the late 1510s, quickly becoming not only his principal assistant but also, according to contemporary accounts like Giorgio Vasari's, his adopted son.

This close personal and professional relationship with Pontormo was fundamental. Bronzino absorbed his master's penchant for elongated forms, vibrant and sometimes unsettling color palettes, and emotionally charged compositions. They collaborated on several significant projects, including the decorations for the Capponi Chapel in Santa Felicita, Florence. While Bronzino would eventually develop his own distinct artistic personality, the foundations laid during his years with Pontormo remained evident throughout his career, particularly in his approach to line and composition.

Pontormo's own eccentric style, marked by intense psychological depth and unconventional beauty, provided a springboard for Bronzino. Yet, where Pontormo often conveyed anxiety and spiritual fervor, Bronzino would channel the Mannerist impulse towards a more polished, controlled, and courtly aesthetic. He refined Pontormo's linearity, smoothing surfaces and emphasizing pristine detail, creating figures that often possess an almost porcelain-like perfection.

Rise to Prominence: The Medici Court Painter

Bronzino's career reached its zenith following his appointment as court painter to Cosimo I de' Medici, Duke of Florence (later Grand Duke of Tuscany), around 1539. This prestigious position provided him with unparalleled access to the ruling elite and secured his financial stability, allowing him to focus on major commissions. The Medici patronage was crucial, shaping the direction of his art towards portraiture and grand allegorical statements befitting the ducal court.

Cosimo I and his cultured Spanish wife, Eleonora di Toledo, were avid patrons of the arts, using painting, sculpture, and architecture to project an image of power, sophistication, and legitimate rule. Bronzino became the primary visual chronicler of their reign. He painted numerous portraits of the Duke, the Duchess, and their children, establishing a new standard for court portraiture that would influence artists across Europe.

These portraits were more than mere likenesses; they were carefully constructed images of status and authority. Bronzino depicted his sitters with an air of aristocratic reserve and cool detachment. The emphasis was often on the sumptuous fabrics of their attire, the intricate details of jewelry, and the flawless rendering of their features, creating an effect of untouchable elegance and formal grandeur. This style perfectly suited the Medici's desire to present themselves as refined yet formidable rulers.

The Hallmarks of Bronzino's Style

Bronzino is considered a quintessential Mannerist painter. His style embodies the movement's core characteristics: maniera, meaning style or grace, often interpreted as a sophisticated artificiality. He moved beyond the High Renaissance goals of harmonious naturalism, instead cultivating an art of exquisite refinement, intellectual complexity, and dazzling technical skill. His figures often display elongated proportions, elegant S-curve poses (the figura serpentinata), and smooth, highly finished surfaces that resemble polished marble or enamel.

His use of color is distinctive – often employing cool, luminous hues with sharp contrasts and unexpected juxtapositions. Lighting in his paintings tends to be even and cold, minimizing dramatic chiaroscuro and contributing to the sense of emotional distance. Detail is paramount; Bronzino rendered textures, patterns, and accessories with painstaking precision, showcasing both his technical virtuosity and the wealth and status of his patrons.

Compared to the warmth and accessibility often found in the works of High Renaissance painters like Raphael, Bronzino's figures can seem aloof and impenetrable. This psychological distance is a key element of his Mannerist approach. His paintings often appeal more to the intellect than the emotions, inviting viewers to decipher complex allegories or admire the sheer perfection of the execution rather than empathize directly with the subjects. This intellectual sophistication was highly valued in the courtly circles in which he moved.

Masterpieces of Portraiture

Portraiture was arguably Bronzino's greatest strength, and his works in this genre remain iconic images of the 16th-century Florentine aristocracy. His depictions of the Medici family are particularly renowned. The Portrait of Eleonora di Toledo and Her Son Giovanni (c. 1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) is perhaps his most famous work. It shows the Duchess in a magnificent brocade dress, rendered with astonishing detail, her hand resting protectively on her young son's shoulder. The painting is a powerful statement of dynastic continuity and maternal pride, yet Eleonora's expression remains distant and impassive, embodying the ideal of aristocratic composure.

Similarly, his portraits of Cosimo I, such as Cosimo I de' Medici in Armour (c. 1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence), project an image of unwavering authority and military strength. The Duke is shown clad in gleaming armor, his gaze direct and commanding. The meticulous rendering of the reflective metal surfaces demonstrates Bronzino's technical brilliance. These official portraits served as important tools of state propaganda, disseminating the Duke's image throughout his territories and beyond.

Bronzino also painted portraits of other members of the court and Florentine society, including poets, scholars, and fellow artists. His Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1530s, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) captures the confident, slightly melancholic air of an aristocratic youth, holding a book as a sign of his learning. The Portrait of Laura Battiferri (c. 1555-1560, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence), depicting the poetess holding a volume of Petrarch, showcases his ability to convey intellectual pursuits alongside physical likeness.

A particularly unusual commission was the double-sided Portrait of the Dwarf Morgante (c. 1553, Pitti Palace, Florence). Depicting Cosimo I's favorite court dwarf nude, first from the front as a hunter and then from the back, the painting was controversial even in its time for its nudity and subject matter. It was later altered for modesty, highlighting the shifting sensibilities regarding representation, even within the relatively liberal court environment. Bronzino also painted a posthumous Portrait of Dante Alighieri (c. 1530), contributing to the visual iconography of Italy's greatest poet.

Allegory and Religious Works

Beyond portraiture, Bronzino excelled in creating complex allegorical and mythological paintings. His most celebrated work in this vein is the Allegory with Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time (also known as An Allegory of Lust, c. 1545, National Gallery, London). Commissioned by Cosimo I as a gift for King Francis I of France, this intricate painting is a prime example of Mannerist intellectualism and eroticism.

The central figures are Venus and her son Cupid, locked in an incestuous embrace. They are surrounded by allegorical figures representing Deceit (a girl offering a honeycomb with a scorpion's tail), Jealousy or Syphilis (a screaming figure tearing its hair), Pleasure or Folly (a boy scattering roses), and Time (an old man pulling back a curtain to reveal the scene). The painting's meaning remains debated but clearly touches upon themes of love's dangers, hidden deceptions, and the fleeting nature of sensual pleasure. The cold, polished rendering of the nude figures and the complex, crowded composition are hallmarks of Bronzino's Mannerist style.

Bronzino also produced significant religious works, although these are sometimes seen as less emotionally engaging than his portraits or allegories. He painted several versions of the Madonna and Child with Saints, often characterized by the same elegant figures and cool palette found in his secular works. Notable examples include the Panciatichi Holy Family (c. 1541, Uffizi) and the Deposition of Christ (c. 1545, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Besançon).

His large-scale religious commissions included frescoes, such as the Resurrection of Christ and decorations in the Chapel of Eleonora di Toledo in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. These works showcase his skill in complex multi-figure compositions and his assimilation of influences from masters like Michelangelo, particularly in the rendering of muscular anatomy. The Martyrdom of St. Lawrence (1569), a late work for the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence, is a vast and crowded composition demonstrating his continued engagement with large-scale narrative painting, though perhaps lacking the freshness of his earlier works.

The Late Period and Religious Shift

Bronzino's later career saw a noticeable increase in the production of religious paintings. This shift can be partly attributed to the changing cultural climate in Italy following the Council of Trent (1545-1563). The Counter-Reformation led to a greater emphasis on decorum and clarity in religious art, with the Church becoming more cautious about potentially lascivious mythological subjects and nudity. Artists across Italy adapted to these new requirements.

While Bronzino continued to work for the Medici, the demand for overtly religious themes grew. His late religious works, such as the Noli me Tangere (c. 1561, Louvre, Paris) or Christ Carrying the Cross (c. 1560s), maintain his characteristic technical polish and elegant figure types. However, critics sometimes note a certain emotional coolness or formality in these later devotional pieces compared to the intensity found in the work of some contemporaries or earlier masters.

During this period, Bronzino also dedicated time to completing works left unfinished by his master Pontormo after the latter's death in 1557, notably the frescoes in the choir of San Lorenzo. This act underscores the enduring bond between the two artists. He remained an active and respected figure in Florence's artistic community until his death.

Bronzino and His Contemporaries

Bronzino operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic milieu in 16th-century Florence and Italy. His primary artistic debt was to Jacopo da Pontormo, his teacher and mentor. He also deeply admired Michelangelo, whose powerful figures and anatomical mastery clearly influenced Bronzino's own approach to the human form, particularly in his religious and allegorical works, though direct personal contact seems limited. The legacy of High Renaissance masters like Raphael and Andrea del Sarto also formed part of the artistic background against which Bronzino developed his Mannerist style.

He was a contemporary of Giorgio Vasari, the artist and biographer whose Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects remains a foundational text for Renaissance art history. Vasari knew Bronzino well and wrote about him, providing valuable insights into his life and work. Other notable contemporaries in Florence included the sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini, another prominent figure at the Medici court, and fellow Mannerist painters like Francesco Salviati and Rosso Fiorentino (though Rosso died earlier).

Bronzino's influence extended to the next generation. His most important pupil was Alessandro Allori, who inherited his workshop and continued working in a style heavily indebted to Bronzino, becoming a leading painter in Florence in the later 16th century. Bronzino's sophisticated court portraiture style also found echoes in the work of artists beyond Florence, contributing to the development of aristocratic portraiture across Europe, competing stylistically with the different, but equally influential, portraiture style of Venetian masters like Titian, or the Emilian elegance of Parmigianino.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

Agnolo Bronzino was one of the dominant artistic forces in Florence for much of the mid-16th century. His role as the official painter to Cosimo I de' Medici placed him at the center of cultural life and ensured the wide dissemination of his style. His portraits defined the image of the Medici court and set a standard for aristocratic representation characterized by elegance, detail, and psychological reserve. His allegorical works, particularly the Allegory with Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time, remain landmark achievements of Mannerist complexity and sophistication.

For a period, particularly during the 19th and early 20th centuries, Mannerism fell out of critical favor, often dismissed as decadent or overly artificial compared to the perceived naturalism and harmony of the High Renaissance. Bronzino's work, with its cool detachment and emphasis on surface perfection, was sometimes criticized during this time. However, the 20th century saw a major reassessment of Mannerism, recognizing it as a distinct and important stylistic movement reflecting the complex cultural and historical shifts of the 16th century.

Today, Bronzino is widely recognized as a master technician and a key exponent of Mannerism. His paintings are admired for their exquisite craftsmanship, intellectual depth, and compelling, if often enigmatic, beauty. His portraits offer invaluable insights into the world of the 16th-century Italian elite, while his allegories continue to provoke discussion and interpretation. He remains a pivotal figure in the history of Florentine art and a testament to the enduring power of refined, courtly elegance.

Conclusion

Agnolo Bronzino navigated the complex artistic and political landscape of 16th-century Florence with remarkable success. From his training under Pontormo to his long tenure as the favored painter of the Medici, he forged a distinctive Mannerist style that perfectly captured the sophisticated, controlled, and often intellectually demanding tastes of his patrons. His legacy endures primarily through his portraits – cool, elegant, and meticulously detailed records of the ruling class – and his intricate allegories, which challenge viewers with their complex symbolism and refined sensuality. As a master of maniera, Bronzino left an indelible mark on the art of his time and continues to be celebrated for his technical brilliance and unique artistic vision.