Jacques Bellange stands as one of the most distinctive and intriguing figures in the art of the early 17th century. Active primarily in the Duchy of Lorraine, an independent territory at the crossroads of French, German, and Netherlandish cultures, Bellange developed a highly personal and sophisticated style of Mannerism. Though many of his paintings are lost, his surviving etchings and drawings reveal an artist of extraordinary technical skill, profound emotional depth, and a penchant for the theatrical and the elegant. His work, once relegated to relative obscurity, has been increasingly appreciated for its unique contribution to the late flowering of Mannerist art in Europe.

The Shadowy Beginnings and Rise in Nancy

The precise birthdate and origins of Jacques Bellange remain somewhat shrouded in mystery, a common fate for many artists of his era. He is generally believed to have been born around 1575. While his exact birthplace is unconfirmed, scholarly consensus often points to the Bassigny region in the southern part of Lorraine. What is clearer is that by the turn of the century, Bellange was establishing himself as a significant artistic presence.

His early training is also a subject of some speculation. It is plausible that he received initial instruction locally. Some art historians suggest he may have traveled, perhaps to northern Germany, where he could have encountered and been influenced by artists like Frederick Brentel of Strasbourg, a notable miniaturist and etcher. This exposure would have been crucial for developing his own formidable skills in the etching medium. Another figure sometimes mentioned in connection with his formative years is Claude Henriquet, an artist active in Nancy, whom Duke Charles III had invited to decorate parts of his ducal palace. It's conceivable Bellange worked under or alongside Henriquet, gaining experience in large-scale decorative projects.

By 1602, Jacques Bellange is documented in Nancy, the vibrant capital of the Duchy of Lorraine. He quickly rose to prominence, securing the prestigious position of court painter and printmaker to Duke Charles III, a notable patron of the arts. This appointment, which he held until around 1616, placed him at the center of Lorraine's cultural life. His duties would have been diverse, ranging from painting portraits of the ducal family and court dignitaries to creating elaborate decorative schemes for the ducal palace and designing ephemeral decorations for court festivities, ballets, and state entries.

The Artistic Milieu of Lorraine

The Duchy of Lorraine in the late 16th and early 17th centuries was an independent and prosperous state, cultivating a sophisticated court culture. Nancy, its capital, became a significant artistic center, attracting talent from various regions. The dukes of Lorraine, particularly Charles III and his successor Henri II, were keen to emulate the grandeur of other European courts, and art played a crucial role in projecting their power and prestige.

This environment was receptive to the prevailing international style of Mannerism, which had originated in Italy with artists like Parmigianino, Rosso Fiorentino, and Pontormo, and had spread throughout Europe, adapted by artists such as Bartholomeus Spranger at the Imperial court in Prague, and members of the School of Fontainebleau in France, like Francesco Primaticcio and Niccolò dell'Abate. Mannerism, with its emphasis on elegance, artifice, elongated forms, complex compositions, and often intense emotional expression, found fertile ground in the courtly atmosphere of Nancy. Bellange became its most distinguished proponent in Lorraine.

His contemporaries in Nancy included other skilled artists, though none quite matched Bellange's idiosyncratic genius. Later, the city would become famous for the work of Jacques Callot, a younger artist whose style, while also rooted in Mannerism, would evolve towards a more realistic and satirical depiction of the world, particularly in his renowned etchings of the Thirty Years' War. While Callot and Bellange were both masters of etching in Nancy, their artistic temperaments and thematic concerns differed significantly. Another Lorraine artist of note from a slightly later period was Georges de La Tour, whose dramatic chiaroscuro would mark a shift towards Baroque sensibilities.

The Quintessence of Bellange's Style: Late Mannerist Elegance

Jacques Bellange's art is the epitome of late Mannerism, characterized by an extreme refinement and an almost otherworldly elegance. His figures are typically elongated, with slender limbs, swan-like necks, and small heads often adorned with elaborate coiffures or fantastical headwear. Their poses are often contorted, sinuous, and highly artificial, conveying a sense of languor, ecstasy, or intense psychological drama. Draperies swirl and billow in complex, calligraphic folds, seemingly independent of the bodies they clothe, adding to the overall decorative effect and rhythmic energy of his compositions.

His approach to composition is often unconventional, featuring dramatic foreshortening, unusual viewpoints, and a deliberate disregard for classical rules of proportion and spatial coherence. This creates a sense of unease or heightened theatricality, drawing the viewer into a world that is both beautiful and unsettling. Light and shadow are employed with great sophistication to model forms, create atmosphere, and enhance the emotional impact of his scenes. His line, particularly in his etchings, is fluid, nervous, and incredibly expressive.

Bellange's style shows a synthesis of various influences. The elegance and elongated proportions recall Italian Mannerists like Parmigianino and the artists of the School of Fontainebleau. There are also echoes of Northern European traditions, particularly in the meticulous detail and the sometimes grotesque or earthy characterization of secondary figures, such as his depictions of beggars. Artists like Hendrick Goltzius in the Netherlands, with his virtuoso printmaking and extravagant figures, provide a parallel to Bellange's own explorations of form and technique. The influence of earlier printmakers like Albrecht Dürer or Lucas van Leyden might also be discerned in the technical ambition of his etchings.

Themes and Subject Matter: Piety, Mythology, and the Everyday

Bellange's surviving oeuvre, primarily his etchings and drawings, explores a range of subjects, though religious themes predominate. His interpretations of biblical narratives are imbued with a fervent, almost mystical piety, characteristic of the Counter-Reformation sensibility that was strong in Lorraine. These are not straightforward devotional images but are often charged with intense emotion and a sense of spiritual drama.

Mythological subjects also feature in his work, often treated with a similar elegance and psychological intensity. These scenes provided opportunities to explore the nude figure and to delve into narratives of love, loss, and transformation, popular themes in Mannerist art. He also produced a few genre scenes, most notably his depictions of beggars, which, while stylized, possess a raw energy and a keen observation of human character.

His role as a court artist would have also involved portraiture, though few, if any, painted portraits can be securely attributed to him today. However, the refined and individualized features of many figures in his religious and mythological compositions suggest a strong capacity for capturing likeness and character. One documented, though now lost, painting depicted ten Roman emperors, indicating an engagement with historical subjects as well, likely for ducal commissions.

Mastery of the Etching Medium

While Bellange was a painter, it is through his etchings that his genius is most fully appreciated today. He was a virtuoso of the etching needle, exploiting the medium's potential for fluid lines, rich tonal variations, and expressive freedom. He often combined etching with engraving and drypoint to achieve a wider range of textures and effects.

His technique was innovative. He is known to have used multiple bitings of the copper plate in the acid bath, allowing him to achieve varying depths and strengths of line, contributing to the painterly quality of his prints. Irregular etching and delicate burnishing were also part of his technical arsenal, creating subtle atmospheric effects and highlights. This technical sophistication allowed him to translate his highly personal vision into print with remarkable fidelity.

The dissemination of prints was a crucial aspect of artistic exchange in the 17th century, and Bellange's etchings would have circulated beyond Lorraine, carrying his unique style to a wider audience. His prints were not merely reproductive but were original artistic statements, valued for their intrinsic beauty and technical brilliance. He stands alongside artists like Giorgio Ghisi, who famously translated the works of painters like Luca Penni into engravings, as a master who elevated printmaking to a high art form.

An Examination of Key Works

Several of Bellange's etchings stand out as masterpieces, encapsulating his distinctive style and thematic concerns.

The Three Marys at the Tomb: This is perhaps Bellange's most famous and iconic etching. It depicts the three women arriving at Christ's empty sepulcher, an angel seated on the tomb. The figures of the Marys are extraordinarily elongated and elegant, their grief expressed through graceful, almost dance-like gestures and sorrowful expressions. Their voluminous draperies swirl around them, creating dynamic, abstract patterns. The composition is daring, with the figures pushed to the foreground and the tomb rendered with a dramatic perspective. Bellange even breaks temporal unity by depicting one of the Marys twice, once approaching and once reacting at the tomb, enhancing the narrative and emotional flow. The overall effect is one of profound spiritual intensity, conveyed through a highly artificial and refined visual language.

The Annunciation: In this exquisite print, the Archangel Gabriel appears before the Virgin Mary. Both figures are characterized by an ethereal grace and elongated proportions. Gabriel's wings are a marvel of delicate feathering, and his gesture is one of gentle reverence. Mary, interrupted in her reading, responds with demure surprise. The composition is balanced yet dynamic, with a strong sense of divine light illuminating the scene. The intricate details of the setting and the delicate rendering of textures showcase Bellange's technical finesse.

The Raising of Lazarus: This etching captures the dramatic moment when Christ calls Lazarus forth from the tomb. The composition is crowded and animated, filled with figures reacting with astonishment and awe. Lazarus himself is depicted as an emaciated figure, still wrapped in his grave clothes, a stark contrast to the elegant vitality of Christ and the onlookers. Bellange masterfully conveys the emotional turmoil and the miraculous nature of the event through expressive gestures and facial expressions. The use of light and shadow is particularly effective in heightening the drama.

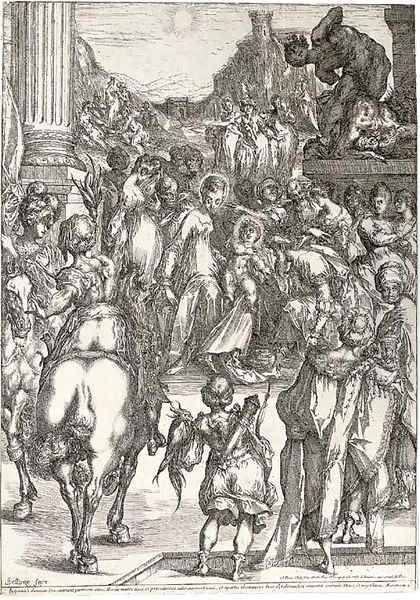

The Adoration of the Magi: Another complex and richly detailed religious scene, this print showcases Bellange's ability to orchestrate large groups of figures. The three Magi, in their exotic attire, present their gifts to the infant Christ, who is held by a typically elegant Virgin Mary. The retinue of the Magi, including camels and attendants, fills the background, creating a sense of pageantry and splendor. Each figure is carefully individualized, and the overall composition is a tour-de-force of Mannerist design.

Diana and Orion (or Diana and Actaeon): This mythological print, like others such as The Gardener (sometimes interpreted as Vertumnus and Pomona), demonstrates Bellange's engagement with classical themes. These works often carry an erotic charge, typical of Mannerist interpretations of mythology. The figures are rendered with his characteristic sensuous elegance, and the compositions are often intricate and decorative. Such prints likely appealed to the sophisticated tastes of his courtly patrons.

The Combat of Two Beggars: This print, along with others depicting single figures of beggars or "gueux," shows a different facet of Bellange's art. While still stylized, these figures possess a raw, earthy quality. Their ragged clothes, gnarled limbs, and expressive faces convey a sense of hardship and resilience. These works connect Bellange to a Northern European tradition of depicting peasant life and social outcasts, seen in the work of artists like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, though Bellange's interpretation is filtered through his distinctive Mannerist lens.

His series of Apostles also deserves mention. Each apostle is depicted as a monumental, solitary figure, often in a dynamic pose, characterized by intense spiritual contemplation or visionary fervor. These prints are powerful studies of character and emotion, rendered with Bellange's typical linear energy.

Influences and Artistic Lineage

Bellange's art did not emerge in a vacuum. He absorbed and transformed various artistic currents. The influence of the School of Fontainebleau, with its elegant and eroticized Mannerism, is palpable. Italian artists like Parmigianino, with his graceful elongations, and Domenico Beccafumi, with his flickering light and intense spirituality, seem to be important touchstones. The prints of Northern Mannerists like Goltzius, with their technical bravura and extravagant forms, also likely played a role in shaping his approach.

Within Lorraine, Bellange was a dominant figure during his active years. While it is difficult to trace a direct school of followers who precisely emulated his highly personal style, his presence undoubtedly enriched the artistic environment of Nancy. Artists like Georges Lallemant, who was active in Nancy during his youth before moving to Paris, may have absorbed aspects of Bellange's manner. Lallemant, in turn, became the teacher of important French painters like Philippe de Champaigne and Laurent de La Hyre, though their styles would move towards a more classical Baroque.

Bellange's work can be seen as a late, brilliant manifestation of an international courtly style that was soon to be superseded by the more robust naturalism and dramatic power of the Baroque, as exemplified by artists like Caravaggio in Italy or Peter Paul Rubens in Flanders. Even in France, the classicizing tendencies of artists like Nicolas Poussin would eventually hold sway.

Later Career, Obscurity, and Rediscovery

Information about Bellange's career after he ceased to be court painter around 1616 is scarce. He is recorded as marrying Claude Bergeron, the daughter of a prominent apothecary and a widow herself, in 1617. This marriage brought him considerable property and social standing. He seems to have largely retired from his artistic activities, or at least his production significantly diminished. He died in Nancy in 1638.

For centuries, Jacques Bellange remained a relatively obscure figure, overshadowed by later artists and by the general decline in appreciation for Mannerism. His highly stylized and sometimes eccentric art did not conform to the classical tastes that dominated much of the 18th and 19th centuries.

It was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that art historians and collectors began to rediscover the unique qualities of Mannerist art in general, and Bellange's work in particular. Scholars like A. P. F. Robert-Dumesnil in the 19th century cataloged his prints, and in the 20th century, figures such as Anthony Blunt and Jacques Thuillier played crucial roles in reassessing his significance. Exhibitions dedicated to his work, and to Mannerism more broadly, further enhanced his reputation. Today, his etchings are highly prized by collectors and museums, and he is recognized as one ofthe most original and compelling printmakers of his time. His work is seen as a fascinating expression of the complex cultural and spiritual currents of early 17th-century Europe.

Enduring Legacy: An Artist of Singular Vision

Jacques Bellange's legacy rests on his extraordinary ability to create a world of intense beauty, spiritual fervor, and psychological depth through a highly artificial and refined artistic language. His elongated figures, swirling draperies, and dramatic compositions are instantly recognizable, marking him as an artist of singular vision. While the bulk of his painted oeuvre is lost, his surviving etchings and drawings provide ample evidence of his genius.

He represents a fascinating chapter in the history of Mannerism, demonstrating the style's enduring vitality and its capacity for regional variation. His position in Lorraine, at a cultural crossroads, allowed him to synthesize diverse influences into something entirely his own. In an era that saw the rise of great printmakers like Callot and, later, Rembrandt van Rijn, Bellange carved out a unique niche with his painterly approach to etching and his exploration of the extremes of human emotion and spiritual experience.

His art continues to captivate and intrigue modern audiences, who find in his work a sophisticated elegance, a profound emotional resonance, and a touch of the bizarre that speaks to contemporary sensibilities. Jacques Bellange may have been an artist of a specific time and place, but the power and originality of his vision transcend historical boundaries, securing his place as a master of European art.