Edmond-François Aman-Jean (1858-1936) stands as a significant, if sometimes understated, figure in the rich tapestry of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century French art. Primarily recognized for his contributions to the Symbolist movement, Aman-Jean carved a niche for himself with his ethereal depictions of women, his delicate use of color, and his ability to imbue his subjects with an air of introspection and mystery. His career spanned a period of immense artistic upheaval and innovation, yet he maintained a distinctive voice, navigating the currents of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and burgeoning modernism while staying true to a more poetic and decorative sensibility.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Chevry-Cossigny, Seine-et-Marne, France, on January 13, 1858, Edmond-François Aman-Jean's artistic journey began with formal training that would shape his early development. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a bastion of academic tradition. There, he studied under Henri Lehmann, a painter known for his classical compositions and portraits, who himself had been a pupil of the great Neoclassicist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. This grounding in academic drawing and composition provided Aman-Jean with a solid technical foundation.

However, the rigid academicism of Lehmann's studio did not entirely satisfy the young artist. He also sought inspiration and guidance from Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, one of the most revered muralists and painters of the era. Puvis de Chavannes, known for his serene, allegorical compositions and muted palettes, exerted a considerable influence on a generation of artists, including Aman-Jean. His emphasis on simplified forms, harmonious color schemes, and a sense of timelessness resonated with Aman-Jean's burgeoning aesthetic.

A Pivotal Friendship: Aman-Jean and Georges Seurat

During his time at the École des Beaux-Arts, Aman-Jean formed a close and artistically significant friendship with Georges Seurat. Seurat, who would later become the pioneer of Pointillism and Neo-Impressionism, was a fellow student in Lehmann's atelier. The two young artists found common ground in their desire to explore beyond the confines of strict academic teaching. They shared a studio for a period, a common practice for aspiring artists seeking mutual support and a dedicated workspace.

This collaboration was more than just practical; it was a period of shared artistic exploration. Both Aman-Jean and Seurat were keen observers of contemporary artistic developments and scientific theories of color and light. They reportedly studied classical art at the Louvre together and discussed the optical theories of scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood, which were becoming influential in artistic circles. They even traveled together, notably to the island of La Grande Jatte, a site that would become immortalized in Seurat's masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

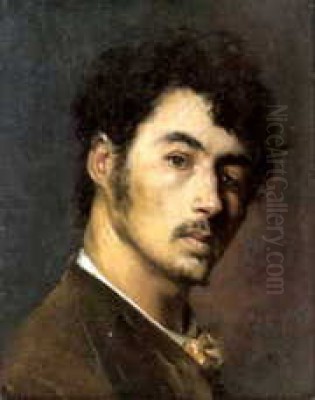

Despite their close association and shared intellectual curiosity, their artistic paths eventually diverged. Seurat dedicated himself to the systematic application of color theory in his Pointillist technique, creating works of rigorous structure and optical brilliance. Aman-Jean, while undoubtedly influenced by Seurat's explorations of color and light, gravitated towards a more lyrical and subjective approach. He did not adopt the strict methodology of Pointillism, preferring a softer, more atmospheric application of paint and a focus on emotive content. Seurat famously painted a portrait of his friend, Portrait of Aman-Jean (1882-83), a sensitive depiction that captures the introspective nature of the young artist.

Embracing Symbolism

As the 1880s progressed, Aman-Jean found his artistic voice increasingly aligned with the burgeoning Symbolist movement. Symbolism, which emerged as a reaction against Naturalism and Impressionism, sought to depict not objective reality but the subjective world of ideas, emotions, and dreams. Symbolist artists and writers aimed to evoke rather than describe, using symbols, allegories, and suggestive imagery to explore themes of spirituality, mysticism, the inner life, and the femme fatale or the idealized woman.

Aman-Jean became a prominent figure within Symbolist circles. He was acquainted with leading literary figures of the movement, such as the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, whose Tuesday evening gatherings were a hub for Symbolist artists and writers. He also associated with Joséphin Péladan, the eccentric writer and occultist who founded the Salon de la Rose + Croix. This connection was particularly significant for Aman-Jean's public visibility as a Symbolist painter.

The Symbolist aesthetic, with its emphasis on mood, suggestion, and the decorative, suited Aman-Jean's temperament and artistic inclinations. His work began to feature the characteristic motifs of the movement: pensive women, often in profile or lost in thought, surrounded by flowers or evocative, dream-like settings. His palette, while often light, was used to create a sense of atmosphere and emotional resonance rather than purely optical effects. Artists like Gustave Moreau, with his richly detailed mythological scenes, and Odilon Redon, with his mysterious and dreamlike imagery, were key figures in French Symbolism, and Aman-Jean's work shares some of their introspective qualities, though often with a gentler, more decorative touch.

The Salon de la Rose + Croix

Aman-Jean's involvement with Joséphin Péladan's Salon de la Rose + Croix was a defining moment in his career, firmly establishing him as a key painter of the Symbolist movement. Péladan, a flamboyant figure who styled himself as "Sâr" (a pseudo-Assyrian title for "chief"), organized these Salons between 1892 and 1897 with the aim of promoting an art that was idealistic, mystical, and anti-materialist. He rejected Realism, Impressionism, and any art he deemed vulgar or mundane, favoring themes from legend, myth, dream, and allegory.

Aman-Jean exhibited at the first Salon de la Rose + Croix in 1892 at the Durand-Ruel gallery, showing four works, and again in 1893, where he exhibited eight pieces. He also designed the poster for the second Salon in 1893, a significant commission that further highlighted his association with the group. His contributions were well-received within these circles, as his elegant and melancholic depictions of women aligned perfectly with Péladan's aesthetic ideals. Other artists associated with these Salons included Fernand Khnopff, Carlos Schwabe, and Jean Delville, all of whom explored themes of idealism and mysticism in their work.

While the Salon de la Rose + Croix was relatively short-lived, it played a crucial role in consolidating the Symbolist movement and providing a platform for artists like Aman-Jean who sought alternatives to the prevailing artistic trends. His participation underscored his commitment to an art that prioritized the inner world and poetic suggestion.

The Influence of Japonisme

Like many artists of his generation, Aman-Jean was significantly influenced by Japonisme – the European fascination with Japanese art and culture that swept across the continent in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influx of Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, with their bold compositions, flattened perspectives, decorative patterns, and unconventional cropping, offered a fresh visual language that captivated Western artists.

Aman-Jean absorbed these influences into his own work. This can be seen in his use of asymmetrical compositions, his attention to decorative detail, and sometimes in the inclusion of Japanese motifs or objects in his paintings. His work Japanese Woman with a Vase (1923), though later in his career, explicitly acknowledges this interest. More subtly, the flattened spaces, the emphasis on line, and the decorative arrangement of forms in many of his female portraits recall Japanese aesthetic principles. Artists like James McNeill Whistler, Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec were also profoundly impacted by Japonisme, each integrating its lessons in their unique ways. For Aman-Jean, it provided another tool to enhance the decorative and evocative qualities of his art.

Thematic Focus: The Enigmatic Woman

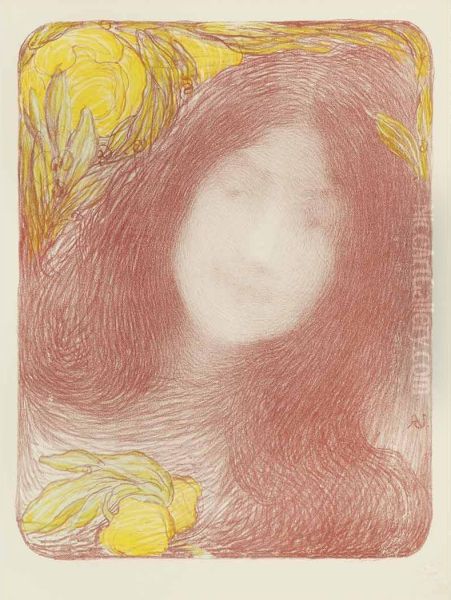

The most consistent and recognizable theme in Aman-Jean's oeuvre is his depiction of women. He became renowned for his portraits and idealized figures of women, often portrayed in moments of quiet contemplation, reverie, or gentle melancholy. These are not typically portraits in the conventional sense of capturing a specific likeness for a commission, but rather explorations of a feminine ideal, imbued with Symbolist sensibility.

His women are often slender, elegant, and ethereal, with elongated necks and delicate features. They are frequently shown in profile or three-quarter view, averting their gaze, which enhances their enigmatic quality. Flowers are a recurring motif, often surrounding the figures or held by them, symbolizing beauty, transience, and the inner life. Works such as Girl with a Peacock (1895) and Sous les fleurs (Under the Flowers, 1897) are prime examples of this focus. In Girl with a Peacock, the rich, decorative plumage of the bird complements the contemplative beauty of the young woman, creating a harmonious and symbolic composition.

These depictions align with the Symbolist fascination with the "eternal feminine," often portraying women as muses, dream figures, or embodiments of spiritual or emotional states. Unlike some Symbolists who explored the darker, more threatening aspects of the femme fatale, Aman-Jean's women are generally serene, graceful, and introspective, inviting the viewer into a world of quiet beauty and poetic feeling. His approach can be compared to some of the idealized female figures found in Pre-Raphaelite art, though with a distinctly French fin-de-siècle sensibility.

Signature Style and Technique

Aman-Jean developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by its delicacy, refinement, and decorative quality. His palette often favored soft, harmonious colors – pastels, muted tones, and subtle gradations – though he could also employ richer hues for decorative effect. He had a preference for a smooth, refined application of paint, avoiding the broken brushwork of the Impressionists or the systematic dots of his friend Seurat.

Line played an important role in his compositions, often elegant and flowing, defining the contours of his figures and contributing to the overall decorative rhythm of the work. He was skilled in creating a sense of atmosphere, often suffusing his scenes with a soft, diffused light that enhanced their dreamlike quality. His compositions were carefully arranged, often with a focus on creating a harmonious balance between the figure and the surrounding elements, such as flowers, textiles, or decorative backgrounds.

While primarily a painter, Aman-Jean also worked in other media, including pastels, lithography, and poster design. His pastels, in particular, allowed him to achieve a softness and luminosity that complemented his subject matter. His skill as a decorative artist was also evident in his designs for posters and his work in mural painting.

Key Works: A Closer Look

Several works stand out as representative of Aman-Jean's artistic vision and style.

Girl with a Peacock (1895, Musée d'Orsay, Paris): This is perhaps one of his most iconic paintings. It depicts a young woman in profile, her gaze contemplative, standing beside a peacock whose magnificent tail feathers create a rich, decorative backdrop. The colors are harmonious, with blues, greens, and golds predominating. The painting embodies the Symbolist interest in beauty, mystery, and decorative elegance. The peacock itself is a symbol rich in associations, from immortality to vanity, adding layers of meaning to the work.

Sous les fleurs (Under the Flowers) (1897): This title, or variations of it, appears for several works, highlighting a recurring theme. These paintings typically feature women surrounded by or adorned with abundant flowers, emphasizing a connection with nature and the ephemeral beauty of both the figures and the blossoms. The mood is often one of quiet reverie, the figures seemingly lost in their own thoughts.

Portrait of Mademoiselle Thérèse Aman-Jean (c. 1892): Aman-Jean also painted portraits of his family members, including his wife, Thérèse Aman-Jean (née Lessore, sister of the painter Émile Lessore), and their children. These portraits often retain the sensitivity and introspective quality of his idealized figures but with a greater sense of individual character.

Japanese Woman with a Vase (1923): This later work demonstrates his continued interest in Japonisme. The composition, the attire of the figure, and the inclusion of a decorative vase all point to Japanese influences, integrated into his characteristic style of elegant figuration.

His mural work, such as commissions for the Sorbonne in Paris, allowed him to apply his decorative and allegorical style on a larger scale, contributing to the tradition of public art in France, a field also notably explored by his mentor Puvis de Chavannes.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Career

Aman-Jean achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. He began exhibiting at the Paris Salon in 1883, where Seurat's portrait of him was shown. He also exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Indépendants, a venue established by artists like Seurat, Paul Signac, and Odilon Redon as an alternative to the official Salon. His regular participation in the Salons of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, where he also served as a jury member, further solidified his reputation.

His involvement with the Salon de la Rose + Croix, as previously mentioned, was crucial. Later in his career, in 1923, Aman-Jean co-founded the Salon des Tuileries with other prominent artists, including Albert Besnard and, according to some sources, with the spirit of Auguste Rodin (who had passed away in 1917 but whose influence was still strong) in mind. This Salon became a significant annual exhibition in Paris, running until the 1950s, and provided a platform for a wide range of artistic styles.

Aman-Jean's contributions to French art were officially recognized when he was made a Commander of the Legion of Honour, one of France's highest civilian awards. This indicates the esteem in which he was held by the artistic establishment and the public. He continued to paint and exhibit throughout his career, adapting subtly to changing tastes while largely maintaining his signature style. His work was appreciated for its charm, elegance, and poetic sensibility, offering a gentler, more introspective counterpoint to some of the more radical artistic movements of the early 20th century.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Aman-Jean's career unfolded within a vibrant and diverse Parisian art world. He was a contemporary of Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin (whose later work also embraced Symbolist ideas), and Nabis painters like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who shared an interest in decorative qualities and intimate subjects.

While his friendship with Seurat was formative, his artistic path diverged from Seurat's Neo-Impressionism, which was further developed by artists like Paul Signac. Aman-Jean's Symbolism placed him in the company of artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Fernand Khnopff, though his style was generally less overtly mystical or psychologically intense than theirs. He shared with James McNeill Whistler an interest in subtle harmonies of color and elegant, Whistlerian female figures, often in profile.

His role as a co-founder of the Salon des Tuileries alongside figures like Albert Besnard, a successful painter known for his society portraits and decorative schemes, demonstrates his respected position within the Parisian art establishment of the early 20th century. He navigated this complex world, maintaining his artistic integrity and contributing a distinctive body of work.

Legacy and Conclusion

Edmond-François Aman-Jean passed away in Paris on August 25, 1936. He left behind a significant body of work that captures the refined and introspective spirit of the fin-de-siècle. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, his contribution to Symbolism and his sensitive, decorative depictions of women hold an important place in the history of French art.

His paintings continue to be admired for their delicate beauty, their dreamlike atmosphere, and their embodiment of a certain feminine ideal popular at the turn of the century. They offer a window into a world of poetic reverie and quiet elegance, a counter-narrative to the often-turbulent artistic innovations of his time. Aman-Jean's art reminds us of the diversity of artistic expression during this period and the enduring appeal of works that speak to the inner life and the pursuit of beauty. His legacy is that of a skilled and sensitive artist who successfully translated the ideals of Symbolism into a personal and recognizable visual language, leaving an indelible mark on the art of his era.