Christopher Wood stands as a poignant figure in the landscape of early twentieth-century British art. Born in 1901 and dying tragically young in 1930, his career spanned less than a decade, yet he produced a body of work that continues to fascinate and resonate. He was an artist who navigated the complex currents between the burgeoning modernism of continental Europe, particularly Paris, and a distinctly British sensibility. His paintings, often characterized by a sophisticated yet seemingly simple 'naïve' style, captured landscapes, coastal scenes, and portraits with a unique lyrical freshness, securing his place as a significant, albeit short-lived, talent in British art history.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

John Christopher Wood, known professionally as Christopher Wood, entered the world on April 7, 1901. He was born in Knowsley, a town near the bustling port city of Liverpool in the North West of England. His parents were Lucius and Clare Wood. While details of his earliest artistic training are not extensively documented in every source, it became clear relatively early that his path lay in the arts rather than a more conventional career. His formative years coincided with a period of immense artistic upheaval across Europe, setting the stage for his eventual immersion in the avant-garde circles that would profoundly shape his vision.

The precise moment Wood decided to dedicate himself fully to painting is perhaps less important than the evident passion that drove him. By his late teens and early twenties, he was actively seeking out artistic environments that would nurture his talent. This quest led him, like so many aspiring artists of his generation, away from Britain towards the magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world at that time. This move marked a pivotal turning point in his life and artistic development.

Parisian Exposure and Avant-Garde Encounters

Around the age of twenty, Christopher Wood made the crucial decision to move to Paris. The French capital in the early 1920s was a crucible of artistic innovation, home to groundbreaking movements and legendary figures. Wood immersed himself in this vibrant milieu, quickly establishing connections with some of the leading lights of the avant-garde. He met and associated with towering figures such as the Spanish master Pablo Picasso, whose relentless experimentation was reshaping modern art.

Wood also formed a significant relationship with the multi-talented French writer, filmmaker, and artist Jean Cocteau. This connection proved fruitful, leading to collaborations and exposing Wood further to the intellectual and artistic currents swirling through Paris. His circle also included interactions with other influential artists, potentially including the young Salvador Dalí, who was himself beginning to make waves. This period was one of intense learning and absorption for Wood, as he soaked up the influences of Post-Impressionism, Cubism, and the nascent ideas that would feed into Surrealism.

His talent gained recognition to the extent that he received commissions, including an opportunity to design sets and costumes for Sergei Diaghilev's famed Ballets Russes. Although, according to some accounts, his designs for the ballet Romeo and Juliet were ultimately not used due to a dispute or preference for other artists, the commission itself signifies his growing stature within the Parisian art scene. This exposure to diverse artistic disciplines and leading creative minds profoundly impacted his outlook and technique.

Forging a Personal Style: The 'Faux-Naïf'

While deeply influenced by his experiences in Paris and the works of continental masters, Christopher Wood did not simply replicate the styles he encountered. Instead, he began to synthesize these influences into a distinct artistic language of his own. He became particularly known for cultivating a 'faux-naïf' or pseudo-primitive style. This approach involved deliberately simplifying forms, flattening perspective, and employing a directness of expression that seemed untutored, yet was underpinned by a sophisticated artistic sensibility.

His paintings often featured muted, chalky colour palettes, though sometimes punctuated with brighter accents. The application of paint could appear textured and deliberately unrefined, contributing to the 'naïve' effect. This style shared affinities with the work of self-taught or 'primitive' artists, most notably the French painter Henri Rousseau, whose work was admired by the avant-garde. However, Wood's 'primitivism' was a conscious artistic choice, a way to achieve a sense of authenticity and emotional directness, rather than a result of lacking academic training.

This developing style moved away from the more overt experimentalism of Cubism towards something more personal and lyrical. It allowed him to imbue scenes of everyday life – harbours, fishing boats, rural landscapes – with a quiet poetry and a strong sense of place. His figures often possess a gentle melancholy or a stoic simplicity, rendered without excessive detail but with considerable emotional weight.

Key Themes and Subjects

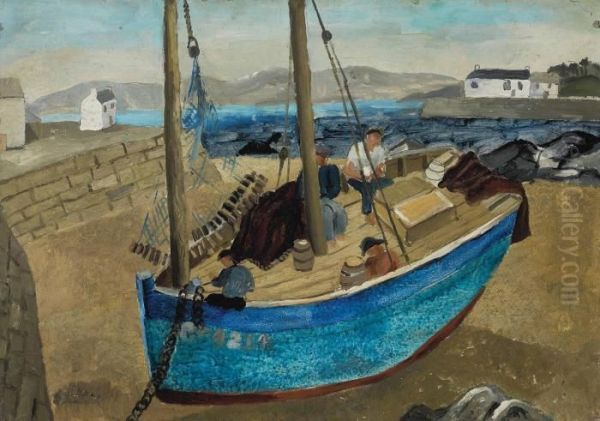

Christopher Wood's subject matter was largely drawn from the world around him, particularly the landscapes and coastal communities of England and France. He had a particular affinity for maritime themes, frequently depicting harbours, fishing boats, sailors, and the rugged coastlines of Cornwall and Brittany. These scenes were not merely picturesque representations; they often conveyed the rhythms of life and work in these communities, sometimes tinged with a sense of introspection or farewell.

Works such as Sleeping Fisherman and Farewell of the Fisherman exemplify this focus on the lives connected to the sea. His landscapes, like Port in the Mountains or The Seaside Cottage, capture specific locations but also evoke a broader atmosphere, often one of tranquility or gentle solitude. He rendered these scenes with his characteristic simplified forms and carefully modulated colours, emphasizing pattern and composition.

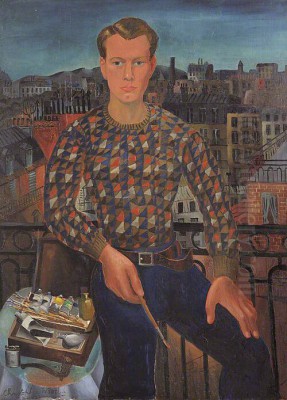

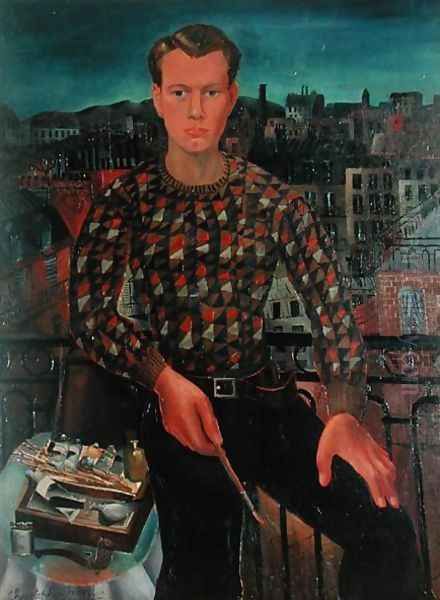

Beyond landscapes and seascapes, Wood also painted still lifes and portraits. His Self-Portrait offers a glimpse into his own persona, rendered with the same stylistic directness he applied to other subjects. Occasionally, more enigmatic or imaginative elements would appear in his work, such as the striking painting Zebra and Parachute, hinting at an engagement with Surrealist ideas, likely absorbed during his time in Paris and his association with figures like Cocteau and Dalí.

Cornwall and the St Ives Connection

A significant chapter in Wood's artistic development unfolded in Cornwall, particularly in the fishing town of St Ives. He visited Cornwall frequently, often in the company of his close friend and fellow artist Ben Nicholson. Nicholson, who would become a central figure in British abstract art, shared Wood's interest in exploring modernism within a British context. Their time painting together in Cornwall was mutually stimulating.

It was in St Ives, in 1928, that Wood and Nicholson encountered the retired mariner and self-taught painter Alfred Wallis. Wallis painted scenes of ships and harbours from memory, using household paints on scraps of cardboard or wood. His direct, untutored style, born from lived experience rather than artistic convention, made a profound impact on both Wood and Nicholson. Wallis's work seemed to embody the authenticity and expressive power that Wood was striving for in his own 'faux-naïf' approach.

Meeting Wallis confirmed Wood's artistic direction, encouraging his embrace of simplified forms, flattened perspectives, and a focus on essential shapes and colours. The influence is palpable in many of Wood's Cornish paintings, such as The Chinese Dog of Saint Ives. The stark beauty of the Cornish landscape and the perceived authenticity of Wallis's vision provided fertile ground for Wood's mature style to blossom.

The London Art Scene and Contemporaries

While Paris and Cornwall were crucial sites of inspiration, Christopher Wood was also an active participant in the London art world. He exhibited his work in London galleries and became associated with important artist groups that were shaping the direction of modern art in Britain. He was a member of The London Group, an exhibiting society founded in 1913 as a more progressive alternative to the Royal Academy.

Membership in The London Group placed him alongside established and emerging figures of British modernism, including the influential Walter Sickert, the sculptor Jacob Epstein, and the Vorticist painter and writer Wyndham Lewis. Wood also joined the Seven and Five Society in the late 1920s. This group, initially focused on traditionalism, evolved under Ben Nicholson's influence to become a key forum for abstract and avant-garde art in Britain, later including artists like Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore (though Moore's direct interaction with Wood is less documented).

Wood maintained friendships with fellow artists like Augustus John, a more established figure known for his portraiture and bohemian lifestyle. His relationship with contemporaries like Wyndham Lewis was complex; they were part of the same milieu and sometimes competitors, as seen in the vying for the Diaghilev commission. Interestingly, despite the prominence of figures like Roger Fry and the Bloomsbury Group in promoting Post-Impressionism in Britain earlier in the century, specific records detailing significant personal interactions between Wood and Fry are scarce according to the available information. Wood navigated this scene, absorbing influences while maintaining his unique trajectory.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Christopher Wood's oeuvre, though produced over a short period, contains several paintings that are considered representative of his unique style and contribution. His Self-Portrait (c. 1927) presents a compelling image of the artist, rendered with his characteristic blend of sophistication and apparent simplicity. The gaze is direct, the features simplified, conveying a sense of youthful intensity and perhaps underlying vulnerability.

Paintings inspired by his time on the coast are central to his legacy. The Beachgoers, Piers and Boats captures the atmosphere of seaside life, likely drawing on observations from Cornwall or Brittany. The composition is carefully structured, using flattened forms and a harmonious colour palette to create a scene that is both descriptive and decorative. Similarly, The Seaside Cottage evokes a strong sense of place through simplified architectural forms and a focus on light and atmosphere.

His maritime paintings often carry emotional depth. Farewell of the Fisherman depicts a poignant moment, rendered with minimal detail but maximum expressive impact through posture and composition. Sleeping Fisherman offers a quieter, more introspective scene. The unusual and imaginative Zebra and Parachute (1930) stands out, suggesting a flirtation with Surrealism and showcasing his ability to move beyond purely observational subjects into realms of fantasy, possibly reflecting the turbulent inner state of his final year.

Later Years and Tragic Demise

Despite his growing recognition and artistic output, Christopher Wood's final years were overshadowed by personal struggles. He developed an addiction to opium, a drug whose use was not uncommon in certain artistic and bohemian circles at the time but which took a heavy toll on his physical and mental health. Friends observed increasing signs of paranoia and erratic behaviour as his addiction deepened.

The tragic end came on August 21, 1930. Wood, aged just 29, had travelled to Salisbury to meet his mother and sister for lunch. He reportedly showed them a selection of his latest paintings. Afterwards, while at Salisbury railway station, apparently waiting for a train to London, he deliberately threw himself under an incoming train. His death was officially ruled a suicide.

The circumstances surrounding his death contained elements that added to its tragic mystery. Some accounts mention he was carrying a revolver at the time, perhaps indicative of his paranoid state. Reports also noted unusual details about his attire when found, possibly including a red sweater and pyjamas, though specifics vary. Ultimately, his death is widely attributed to the devastating effects of his opium addiction and the accompanying mental breakdown, cutting short a career filled with immense promise.

Legacy and Market Recognition

Christopher Wood's death at such a young age meant his full potential remained unrealized. However, the work he did produce secured his reputation as a significant figure in British art between the wars. He is often seen as a vital link between the British art scene and the developments happening on the continent, particularly in Paris. His ability to absorb avant-garde influences while forging a personal, often lyrical and seemingly naïve style, set him apart.

His work resonated with subsequent generations of British artists interested in exploring forms of expressive figuration and landscape painting outside of pure abstraction or academic realism. Posthumous exhibitions helped solidify his reputation, and his paintings are held in major public collections, including the Tate Gallery in London.

In recent decades, Christopher Wood's work has also found increasing favour on the art market. While perhaps not reaching the stratospheric prices of some of his internationally renowned contemporaries like Picasso, his paintings command significant sums, reflecting a growing appreciation for his unique contribution. For instance, his 1924 painting Female Nude achieved a strong price relative to its estimate when sold. A notable auction result occurred in March 2022, when his 1929 painting The Wooden House sold for £441,000 at Phillips in London, setting a new auction record for the artist and demonstrating the enduring appeal and market value of his work.

Conclusion: An Enduring Enigma

Christopher Wood remains an enigmatic and compelling figure in the story of modern British art. His life was tragically short, yet his artistic journey was remarkably rich and productive. He successfully navigated the complex relationship between native traditions and international modernism, absorbing lessons from Picasso, Cocteau, and the Parisian avant-garde, while also finding profound inspiration in the untutored vision of Alfred Wallis and the landscapes of Cornwall.

His distinctive 'faux-naïf' style, characterized by simplified forms, subtle colour harmonies, and a focus on everyday subjects imbued with quiet emotion, marks him as an original talent. He captured a particular mood prevalent in the inter-war years, a blend of lyrical observation and underlying melancholy. Though his career was abruptly ended by personal demons and addiction, Christopher Wood left behind a body of work that continues to be admired for its unique charm, sophisticated simplicity, and its poignant reflection of a brief, brilliant life in art.