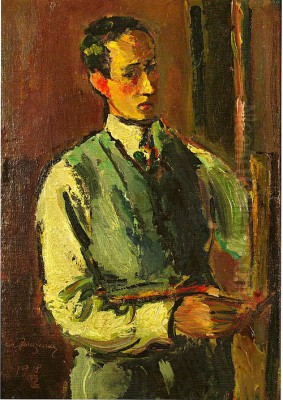

Anton Faistauer stands as a significant figure in the landscape of early 20th-century Austrian art. Born on February 14, 1887, and passing away prematurely on March 13, 1930, Faistauer navigated the turbulent currents of modernism, leaving behind a body of work characterized by vibrant colour, structural integrity, and a deep engagement with both tradition and innovation. As a painter, muralist, and writer, he played a crucial role in the development of Austrian Expressionism, challenging academic conservatism and forging a path that synthesized international influences with a distinctly Austrian sensibility. His life, though relatively short, was marked by intense artistic activity, collaboration, and a commitment to infusing art with spiritual and emotional depth.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Anton Faistauer's origins were rooted in the rural landscape of the Salzburg region. Born in St. Martin bei Lofer, he grew up on his family's farm near Maishofen. This connection to the land and a traditional way of life perhaps informed the earthy tones and grounded quality found in some of his later works. Initially, the young Faistauer harboured aspirations quite different from an artistic career; he considered entering the priesthood, suggesting an early inclination towards spiritual and contemplative pursuits.

However, his path took a decisive turn during his secondary school years in Bozen (Bolzano). A fateful encounter with Albert Paris Gütersloh, another aspiring artist who would become a key figure in Austrian modernism, ignited Faistauer's passion for painting. Gütersloh, known for his multifaceted talents as a painter, writer, and actor, likely exposed Faistauer to new artistic ideas circulating at the time. This meeting proved pivotal, redirecting Faistauer's ambitions from the clergy towards the canvas and setting him on the course that would define his life.

Formative Years in Vienna: Education and Rebellion

Seeking formal training, Faistauer moved to Vienna, the vibrant cultural capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Between 1904 and 1906, he honed his foundational skills at the private painting school of Robert Scheffer. Following this preparatory period, he gained admission to the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, a bastion of artistic tradition. There, he studied under professors such as Alois Delug and the notoriously conservative Christian Griepenkerl.

The Academy, however, proved to be a stifling environment for Faistauer and several of his contemporaries. Griepenkerl, in particular, represented an academicism that seemed increasingly out of step with the dynamism of modern European art. The rigid curriculum and resistance to new forms of expression fostered a sense of frustration among the more forward-thinking students. This dissatisfaction was not unique to Faistauer; it reflected a broader tension in Vienna between established institutions and the burgeoning forces of modernism, famously embodied by the Vienna Secession movement led by artists like Gustav Klimt just a few years earlier.

The Neukunstgruppe: A Stand Against Conservatism

The simmering discontent within the Academy boiled over in 1909. Faistauer, unwilling to conform to the institution's rigid expectations, took a bold step. Together with a group of like-minded young artists, he co-founded the "Neukunstgruppe" (New Art Group). This collective served as an act of defiance against the Academy's perceived artistic stagnation and its conservative policies.

The founding members of the Neukunstgruppe included some of the most promising talents of their generation: Anton Kolig, Robin Christian Andersen, Franz Wiegele, and, most notably, Egon Schiele. Albert Paris Gütersloh was also closely associated with the group's early activities. Their aim was clear: to create a platform for exhibiting art that embraced innovation, personal expression, and the modern spirit, free from the constraints of academic judgment. The Neukunstgruppe's exhibitions, often held independently, provided a crucial outlet for these artists and signaled a definitive break with the artistic establishment represented by the Academy. This act of rebellion cemented Faistauer's position among the avant-garde of Austrian art.

Artistic Development: Influences and Style

Faistauer's artistic style evolved significantly throughout his career, but it remained deeply rooted in the principles of Expressionism, albeit a distinctively Austrian variant. A pivotal influence on his work was the French Post-Impressionist master, Paul Cézanne. Faistauer admired Cézanne's emphasis on structure, form, and the use of colour to build volume. This influence is visible in Faistauer's own work through his solid compositions, clear articulation of forms, and a departure from purely representational colour towards colour used for expressive and structural purposes.

While embracing modern French influences, Faistauer did not entirely abandon tradition. His work often reveals a dialogue between modern techniques and classical or religious themes. He sought a synthesis, aiming for an art that was both formally innovative and spiritually resonant. His brushwork could be vigorous and textured, characteristic of Expressionism, yet his compositions often retained a sense of order and clarity derived from his study of masters like Cézanne.

His palette varied; sometimes employing the bright, bold colours associated with Expressionism, particularly in landscapes and some portraits. At other times, especially in his religious works and later frescoes, he utilized more subdued, earthy tones, creating a sense of solemnity and gravitas. Compared to the psychological intensity and jagged lines of his contemporary Egon Schiele, or the swirling, agitated brushwork of Oskar Kokoschka, Faistauer's Expressionism often appears more measured, focused on monumental forms and the emotional weight conveyed through colour and composition. His subjects ranged from portraits and landscapes to still lifes and significant religious and allegorical scenes, particularly in his mural work.

Wartime Experiences and Post-War Salzburg

The outbreak of World War I profoundly impacted European society and its artists. Due to health reasons, Anton Faistauer was not conscripted for active military service. However, the war years were not a period of artistic inactivity. He participated in war-themed art exhibitions, such as a notable show in Vienna in 1916. His work from this period, like "Rider and Marching Column" (1918), reflects the era's turmoil while showcasing his developing Expressionist style, particularly his use of colour to convey mood and energy.

After the war and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Faistauer chose to settle in Salzburg. This move marked a significant phase in his career, deeply connecting him to the city's cultural life. In Salzburg, he became a central figure in the local art scene. Together with Felix Albrecht Harta and others, he co-founded the artists' association "Der Wassermann" (The Aquarius). This group aimed to promote modern art in the post-war era, organizing exhibitions and fostering a community of progressive artists in Salzburg, which was perhaps seen as a less saturated, more receptive environment than Vienna at the time.

Beyond painting and organizing, Faistauer also engaged in critical writing. In 1925, he published his influential book, "Neue Malerei in Österreich" (New Painting in Austria). In this text, he articulated his views on the state of contemporary art, notably criticizing what he saw as an overemphasis on formalism. He argued passionately for the importance of spiritual content and emotional depth in painting, advocating for an art that engaged with profound human themes rather than mere aesthetic exercises. This publication solidified his role not only as a practitioner but also as a thoughtful commentator on Austrian modern art.

Monumental Works: The Salzburg Frescoes

A defining aspect of Anton Faistauer's later career was his engagement with large-scale mural painting, particularly frescoes. He received several important commissions in Salzburg, allowing him to work on a monumental scale and integrate his art directly into public spaces. His most celebrated achievement in this medium is undoubtedly the series of frescoes he created in 1926 for the foyer of the Felsenreitschule, one of the main venues of the Salzburg Festival. This space is now often referred to as the "Faistauer Foyer."

These frescoes represented a major undertaking, covering large wall surfaces with complex compositions. The themes likely drew upon local history, the arts, and possibly allegorical or religious subjects, reflecting the cultural significance of the Festival and its venue. Creating these works allowed Faistauer to synthesize his interest in modern form with the tradition of monumental painting, a genre with deep historical roots in religious and public art. His approach combined strong, clear forms, expressive colour, and a sense of grandeur appropriate to the scale and setting.

Tragically, Faistauer's frescoes suffered a grim fate during the Nazi era. Following the Anschluss in 1938, the National Socialists deemed his work "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst), likely due to its modern style and possibly its association with artists and intellectuals viewed unfavourably by the regime. The frescoes were covered over or destroyed. However, their importance was recognized, and after World War II, significant efforts were made to restore them. Their eventual recovery stands as a testament to their artistic merit and their importance as part of Austria's cultural heritage, rescued from ideological destruction. These murals remain a powerful example of Faistauer's ambition and his ability to translate his vision onto a grand scale.

Representative Works and Artistic Themes

While the Salzburg frescoes represent a major part of his legacy, Faistauer's oeuvre includes numerous significant easel paintings. "Reiter und Marschkolonne" (Rider and Marching Column) from 1918 is often cited as a key work from the war period. It exemplifies his colourful Expressionism, capturing the dynamic energy and perhaps the underlying tension of the era through bold hues and active composition.

Faistauer also dedicated considerable effort to religious themes, reflecting his early spiritual inclinations, albeit filtered through a modern artistic lens. He created several altarpieces and triptychs. These works often employed a more subdued, earthy palette compared to some of his landscapes or portraits. The use of darker tones and simplified, powerful forms contributed to a sense of solemnity and spiritual weight, connecting with the long tradition of Christian art while remaining distinctly modern in execution.

Throughout his work, recurring themes emerge: the exploration of human figures, often imbued with a sense of introspection or melancholy; the landscapes of his native Austria, rendered with expressive colour and structural solidity; and the engagement with profound questions of life, death, and spirituality. His commitment, as expressed in his writings, to move beyond mere formalism is evident in the emotional resonance and thematic depth he sought in his paintings and murals. He aimed to create art that spoke to both the eye and the spirit, blending the formal innovations learned from artists like Cézanne with the emotional directness characteristic of Expressionism. Other notable Austrian artists exploring similar paths during this period included Herbert Boeckl, who also engaged with monumental forms and expressive colour.

International Recognition and Artistic Network

Anton Faistauer's reputation was not confined to Austria. His work gained recognition internationally, and he exhibited in several major European art centres. Shows of his paintings were held in cities such as Munich, Paris, Rome, and London, bringing his unique vision of Austrian Expressionism to a wider audience. This international exposure helped to establish his place within the broader context of European modern art.

He maintained connections with a network of fellow artists, both within Austria and beyond. His early association with the Neukunstgruppe members like Schiele, Kolig, and Gütersloh was formative. Later, in Salzburg, his collaboration with figures like Felix Albrecht Harta in founding "Der Wassermann" demonstrated his continued commitment to collective artistic endeavours. He was part of a generation of Austrian artists, including figures like Oskar Kokoschka and Herbert Boeckl, who were grappling with the legacy of Klimt and the Vienna Secession while forging new paths influenced by international movements like French Post-Impressionism and German Expressionism. Faistauer navigated these influences, maintaining his distinct voice while participating in the vibrant artistic dialogues of his time.

Personal Life and Final Years

Despite his artistic successes and growing reputation, Anton Faistauer's personal life was marked by complexities and challenges. Sources indicate periods of personal turmoil, including difficulties in his marital life and relationships with other women. These aspects, while part of his biography, existed alongside his dedicated artistic production.

More significantly, Faistauer struggled with recurring health problems throughout the 1920s. Historical accounts mention issues with his lungs and stomach, requiring medical attention as early as 1925. His condition appears to have worsened over time. In 1930, he underwent surgery for a severe stomach hemorrhage. Tragically, complications arose following the operation, and Anton Faistauer died in Vienna on March 13, 1930, at the relatively young age of 43. His premature death cut short a career that was still evolving and promised further significant contributions. He was laid to rest in Maishofen, the area where he had spent his childhood, bringing his life's journey full circle.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Anton Faistauer is rightly regarded as one of the pioneers of modern art in Austria. He played a vital role in the transition from the decorative elegance of the Vienna Secession towards the more robust, emotionally charged language of Expressionism. His co-founding of the Neukunstgruppe was a crucial act of generational rebellion that helped open doors for avant-garde art in Vienna.

His artistic legacy is characterized by his successful synthesis of diverse influences. He absorbed the structural lessons of Cézanne and the expressive potential of colour from French modernism, yet he integrated these with Austrian traditions, particularly in his monumental and religious works. He championed an art of substance, arguing against superficial formalism and emphasizing spiritual and emotional content. His frescoes, despite their troubled history, remain powerful examples of modern monumental art in Austria.

Today, Faistauer's works are held in major Austrian collections, including the Albertina Museum and the Belvedere in Vienna, and the Salzburg Museum, ensuring their accessibility to the public. His influence extended to subsequent generations of Austrian artists. In his home region, his memory is preserved concretely: the town of Maishofen has established the "Anton Faistauer Trail," a themed hiking path that allows visitors to engage with his life and work in the landscape that shaped his early years. He stands alongside figures like Schiele, Kokoschka, Kolig, and Boeckl as a key contributor to the rich and complex tapestry of Austrian modernism.

Conclusion

Anton Faistauer's career, though tragically brief, was intensely productive and highly significant. As a painter, muralist, and thinker, he navigated the complex artistic landscape of early 20th-century Austria with conviction and a unique vision. By challenging academic norms, embracing international modernism while respecting tradition, and championing an art of emotional depth and spiritual resonance, he carved out a distinct and enduring place in Austrian art history. His works, particularly his powerful frescoes and expressive paintings, continue to testify to his talent and his role as a vital force in the development of Austrian Expressionism.