Pietro Testa, known affectionately as "Il Lucchesino" after his birthplace, stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of seventeenth-century Rome. Born in Lucca in 1612, Testa's relatively short life, which ended tragically in 1650, was marked by intense intellectual curiosity, profound artistic skill, particularly in the medium of etching, and a melancholic temperament that perhaps hindered his broader contemporary success as a painter. His oeuvre, though not vast in terms of finished paintings, is rich in drawings and, most importantly, etchings that reveal a mind deeply engaged with classical antiquity, philosophy, and the expressive potential of the human form. This exploration delves into the life, influences, artistic style, key works, and interactions of Pietro Testa, an artist whose intellectual depth and technical mastery in printmaking secured him a lasting, if at times overlooked, place in the annals of art history.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Lucca and Rome

Pietro Testa's journey into the world of art began in Lucca, a Tuscan city with its own respectable artistic traditions. While details of his earliest training in Lucca are somewhat scarce, it is understood that he received a foundational education there before making the pivotal move to Rome around 1628 or shortly thereafter. Rome, in the early seventeenth century, was the undisputed center of the European art world, a magnet for ambitious artists from across the continent. It was a city teeming with ancient ruins, the patronage of powerful papal families and cardinals, and the presence of groundbreaking artists who were shaping the future of Baroque art.

Upon arriving in Rome, the young Testa sought to immerse himself in this stimulating environment. The city offered unparalleled opportunities for study: the remnants of classical civilization were everywhere, providing direct inspiration, and the collections of patrons and the studios of established masters were crucibles of learning and innovation. It was in this dynamic setting that Testa would begin to forge his artistic identity, navigating the complex currents of classicism and the burgeoning High Baroque.

The Influence of Domenichino and the Carracci Legacy

One of Testa's most significant early associations in Rome was with the studio of Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri). Domenichino was a leading exponent of the classical tradition that had been revitalized by the Carracci family – Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico Carracci – at their academy in Bologna. The Carracci had advocated a return to the study of nature, classical antiquity, and the High Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo, as a corrective to the perceived artificiality of late Mannerism. Domenichino, a pupil of Annibale Carracci in Rome, meticulously upheld these principles, emphasizing clarity of composition, idealized human figures, and emotionally resonant narratives.

Testa's period in Domenichino's workshop, though perhaps not lengthy, would have exposed him to these core tenets. He would have learned the importance of rigorous drawing (disegno), the study of anatomy, and the careful construction of narrative scenes. The intellectual underpinnings of Domenichino's art, which often involved complex allegorical or historical subjects, likely resonated with Testa's own scholarly inclinations. This early grounding in the classical tradition provided a crucial foundation upon which Testa would build his more personal and often idiosyncratic style. The emphasis on disegno, in particular, would prove fundamental to his later mastery as a draughtsman and etcher.

A Brief and Tumultuous Stint with Pietro da Cortona

After his time with Domenichino, Pietro Testa is recorded as having worked for a period in the studio of Pietro da Cortona. Cortona was another towering figure of Roman Baroque art, but his style represented a different, more exuberant and dynamic facet of the era compared to Domenichino's measured classicism. Cortona was a master of vast, illusionistic fresco cycles, characterized by swirling movement, rich color, and a sense of theatrical grandeur, as exemplified in his ceiling frescoes for the Palazzo Barberini.

Testa's association with Cortona, however, was reportedly brief and ended contentiously. Accounts suggest that Testa's independent and perhaps difficult personality clashed with the demands or atmosphere of Cortona's bustling workshop. It is said he was dismissed from the studio. This episode, while unfortunate, highlights a recurring theme in Testa's biography: a certain incompatibility with the conventional structures of artistic patronage and collaboration, and a preference for pursuing his own intellectual and artistic paths. Despite the brevity of this connection, exposure to Cortona's dynamic compositions and painterly energy may have subtly informed Testa's own developing sense of movement and drama, even if his primary allegiance remained closer to the classical pole.

The Circle of Cassiano dal Pozzo and the "Paper Museum"

A more enduring and intellectually fruitful connection for Pietro Testa was his involvement with the renowned scholar and patron Cassiano dal Pozzo. Dal Pozzo was a key figure in Roman intellectual life, a secretary to Cardinal Francesco Barberini (nephew of Pope Urban VIII), and a passionate antiquarian. He initiated a monumental project known as the "Museo Cartaceo" or "Paper Museum," an attempt to create a comprehensive visual archive of all surviving evidence of Roman antiquity, as well as natural history specimens. This involved commissioning numerous artists to produce meticulous drawings of ancient sculptures, reliefs, mosaics, architectural details, and more.

Testa was one of the artists employed by dal Pozzo for this ambitious undertaking. This work provided him with an invaluable opportunity for intensive study of classical art. His task of drawing ancient artifacts honed his skills in observation and precise rendering, and deepened his understanding of classical iconography, form, and narrative. The intellectual environment of dal Pozzo's circle, which included scholars, scientists, and artists like the great French classicist Nicolas Poussin, would have been immensely stimulating for Testa. This experience undoubtedly fueled his own antiquarian interests and informed the complex, often recondite, subject matter of his independent works. The discipline of drawing for the "Paper Museum" also reinforced the linear emphasis that would become a hallmark of his etchings.

Nicolas Poussin: A Guiding Light and Intellectual Kinship

Perhaps the most profound artistic and intellectual influence on Pietro Testa was Nicolas Poussin. Poussin, a French painter who spent most of his career in Rome, was a leading figure of seventeenth-century classicism. He was renowned for his erudite historical, mythological, and biblical scenes, characterized by their clarity, order, intellectual depth, and moral seriousness. Poussin and Testa shared a deep reverence for classical antiquity and a philosophical approach to art-making.

While the exact nature of their personal relationship is debated, the artistic kinship is undeniable. Testa's works often echo Poussin's in their choice of subject matter, their compositional strategies, and their attempts to convey complex allegorical or philosophical ideas. Both artists were drawn to stoic themes and explored the vicissitudes of human fortune, the power of reason, and the lessons of history. Testa, like Poussin, meticulously planned his compositions through numerous preparatory drawings. He absorbed Poussin's method of arranging figures in a frieze-like manner, often parallel to the picture plane, and his use of gesture and expression to convey narrative and emotion. However, Testa's interpretations often possessed a more agitated, melancholic, or even eccentric quality than Poussin's measured gravitas, revealing his distinct artistic personality. Other artists in Poussin's circle, such as the sculptor François Duquesnoy (Il Fiammingo), also contributed to this classicizing intellectual environment in Rome.

Testa's Unique Artistic Vision: Style, Themes, and Intellectualism

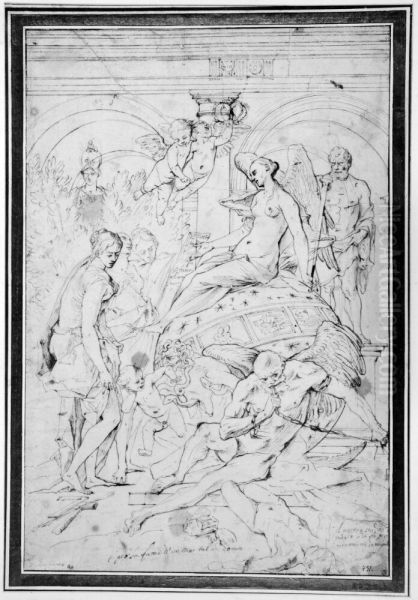

Pietro Testa forged an artistic style that, while rooted in the classical tradition and influenced by figures like Poussin, was uniquely his own. His work is characterized by a dynamic interplay of line, a dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and a penchant for complex, often densely populated compositions. While he aspired to success as a painter, his surviving paintings are relatively few and some are in poor condition. It is in his drawings and, especially, his etchings that his artistic vision is most fully and powerfully realized.

Testa's themes were predominantly drawn from mythology, ancient history, allegory, and the Bible. He was not merely illustrating these stories but using them as vehicles for exploring profound philosophical and moral concepts. His works often carry layers of meaning, sometimes obscure to the uninitiated, reflecting his deep learning and his engagement with Neoplatonic philosophy, alchemy, and other esoteric traditions. This intellectualism set him apart from many of his contemporaries. He was an artist-thinker, whose creations were intended to stimulate the mind as well as delight the eye. His figures, while often classically inspired, can exhibit an expressive intensity and a sense of psychological turmoil that is distinctly Baroque. Artists like Salvator Rosa, another independent and intellectual figure in Rome, shared a similar interest in philosophical themes and dramatic landscapes, though their stylistic approaches differed.

Mastery of Etching: Technique and Innovation

Pietro Testa's most significant contribution to art history lies in his mastery of the etching medium. Etching, a printmaking process where a design is incised into a wax-covered metal plate with a needle and then bitten by acid, allowed for a freedom and spontaneity of line akin to drawing. Testa exploited these qualities to an extraordinary degree, creating prints of remarkable complexity, dynamism, and tonal richness.

His etchings are characterized by a vibrant, calligraphic line that defines form, creates texture, and conveys movement. He was a master of building up dense networks of cross-hatching to achieve deep shadows and dramatic contrasts, lending his prints a powerful, almost sculptural quality. Testa often pushed the technical boundaries of the medium, experimenting with different biting times and sometimes combining etching with engraving or drypoint to enhance the effects. His prints are not mere reproductions of paintings or drawings but are conceived as independent works of art, fully exploiting the expressive potential of the etched line. In this, he can be compared to other great etchers of the era, such as Rembrandt van Rijn in Holland or Jacques Callot in France, though Testa's style and subject matter were distinctly Italian and classicizing. Stefano della Bella was another contemporary Italian etcher of note, though with a lighter, more decorative touch.

Key Works and Their Significance

Pietro Testa produced a body of etchings that remain compelling for their technical brilliance and intellectual depth. Several stand out as particularly representative of his artistic concerns.

The Sacrifice of Isaac: This powerful etching, existing in several states, showcases Testa's ability to convey intense emotion and drama. The dynamic composition, with Abraham's desperate lunge and Isaac's terrified resignation, is heightened by the swirling energy of the angel and the dramatic use of light and shadow. The landscape itself seems to participate in the emotional turmoil of the scene. This work reflects Testa's engagement with biblical narratives that explore themes of faith, obedience, and divine intervention, themes also explored by contemporaries like Caravaggio in painting, albeit with a different stylistic language.

The Massacre of the Innocents: Another highly dramatic and emotionally charged print, The Massacre of the Innocents is a tour-de-force of complex figural composition and expressive intensity. Testa fills the scene with a maelstrom of struggling figures – desperate mothers, brutal soldiers, and dying children – creating a visceral depiction of cruelty and suffering. The work demonstrates his ability to orchestrate large groups of figures in dynamic interaction, a skill honed through his study of classical reliefs and Renaissance masters like Raphael, whose own depiction of this subject was influential.

The Four Seasons (Allegory of Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter): This series of large and complex allegorical etchings represents one of Testa's most ambitious undertakings. Each print is a dense tapestry of mythological figures, symbolic animals, and lush landscapes, embodying the characteristics and activities associated with each season. These works are rich in arcane symbolism and reflect Testa's deep engagement with classical literature and allegorical traditions. They are not simply decorative representations but philosophical meditations on the cycles of nature, time, and human life. The ambition of these prints is comparable to large-scale painted allegories by artists like Pietro da Cortona or even Peter Paul Rubens further north.

Alexander the Great Rescued from the River Cydnus: This subject, drawn from classical history, allowed Testa to explore themes of heroism, vulnerability, and the caprices of fortune. The composition typically shows the near-drowning Alexander being pulled from the icy waters by his soldiers. Testa's rendition emphasizes the drama of the moment and the physical exertion of the figures, showcasing his skill in rendering anatomy and dynamic movement.

Other notable prints include The Garden of Venus, The Triumph of Painting over Ignorance, and various mythological scenes and complex allegories that often require considerable iconographic deciphering. These works consistently demonstrate his fertile imagination, his scholarly depth, and his extraordinary command of the etching needle. His approach to landscape, often wild and imbued with a sense of ancient mystery, also finds parallels in the work of contemporaries like Gaspard Dughet (Poussin's brother-in-law) and Claude Lorrain, though Testa's landscapes are usually settings for complex figure compositions rather than the primary subject.

Relationships with Other Contemporaries

Beyond his formative influences and key patrons, Pietro Testa moved within a broader artistic and intellectual milieu in Rome. He was acquainted with Giovanni Pietro Bellori, one of the most important art theorists and biographers of the seventeenth century. Bellori's writings, which championed classicism and the ideal, provide valuable context for understanding the intellectual currents that shaped artists like Testa and Poussin.

While Testa's melancholic and reportedly difficult temperament may have limited his close friendships, he was part of a community of artists. He would have known of, and likely interacted with, other painters and sculptors active in Rome. These included figures like Andrea Sacchi, another proponent of classicism who famously debated with Pietro da Cortona about the principles of composition (the "few figures" versus "many figures" debate). The dominant sculptor of the era, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, whose dynamic and theatrical Baroque style defined Roman art for decades, represented an artistic pole somewhat different from Testa's more Poussinist leanings, yet his pervasive influence was inescapable. Alessandro Algardi, another prominent sculptor, offered a more classical alternative to Bernini.

Testa's friendship with the painter Francesco Mola (Pier Francesco Mola) is also documented. Mola, like Testa, had connections to northern Italian artistic traditions and developed a rich, painterly style. Such relationships, even if not always smooth, were part of the fabric of artistic life, involving shared discussions, rivalries, and the exchange of ideas.

The Melancholic Temperament and Personal Struggles

Biographical accounts, notably those by Filippo Baldinucci and Giovanni Battista Passeri, paint a picture of Pietro Testa as a man of intense, brooding intellect, prone to melancholy and dissatisfaction. He was described as shy, introverted, and perhaps overly critical of himself and others. This temperament, while possibly fueling his profound and often somber artistic explorations, seems to have hindered his career in practical terms.

His ambition to be recognized primarily as a painter was largely unfulfilled. Despite his talent, he struggled to secure major painting commissions, which were the main route to fame and fortune for artists of his era. This lack of success in painting, contrasted with his evident mastery in etching, may have been a source of frustration. His independent spirit and reluctance to cater to the tastes of patrons, or his difficulty in navigating the social intricacies of the art world, likely contributed to his professional challenges. He preferred, it seems, to work on his own complex, self-driven projects, which, while artistically rewarding, may not have been commercially lucrative. Financial difficulties and psychological stress are reported to have plagued his later years.

Final Years and Tragic Demise

The circumstances of Pietro Testa's death in 1650, at the young age of 38 or 39, are shrouded in some mystery and sadness. The most common account, relayed by his biographers, is that he died by suicide, drowning himself in the Tiber River in Rome. Some versions suggest it was an accident while he was sketching the river's moods or effects of light, but the narrative of suicide, driven by despair over his lack of recognition, financial woes, and his melancholic disposition, has persisted.

This tragic end cut short a career that, particularly in the realm of printmaking, was already remarkably accomplished and promised further development. His death deprived the Roman art world of a unique and intellectually potent voice. The image of the solitary, misunderstood genius, toiling in obscurity and meeting a premature end, adds a layer of romantic pathos to his biography, though it's important to separate the man from the myth.

Legacy and Posthumous Reputation

Despite the challenges he faced during his lifetime, Pietro Testa's etchings ensured his posthumous reputation. His prints were collected and admired by connoisseurs and fellow artists for their technical virtuosity and intellectual depth. They circulated widely, influencing later generations of printmakers. In the eighteenth century, there was a significant revival of interest in his work, and his prints were sought after by collectors like Pierre-Jean Mariette in France.

However, his paintings remained less known and appreciated, partly due to their scarcity and condition. For a long time, Testa was primarily categorized as a "painter-etcher," with the emphasis often falling on the latter. Modern scholarship, particularly since the mid-twentieth century, has done much to re-evaluate Testa's entire oeuvre, including his numerous preparatory drawings, which reveal the meticulous intellectual process behind his creations. Exhibitions and scholarly publications have shed more light on his complex iconography, his philosophical preoccupations, and his unique position within the Roman Baroque. He is now recognized as a highly original artist whose intellectual ambition was matched by his technical skill, particularly in the demanding medium of etching. His work continues to fascinate for its blend of classical learning, Baroque dynamism, and a deeply personal, often melancholic, sensibility.

Conclusion: A Luminous Mind in a Somber Hue

Pietro Testa remains a compelling figure in the rich tapestry of seventeenth-century Roman art. "Il Lucchesino" was an artist of profound intellect and searching spirit, whose primary legacy lies in his extraordinary body of etchings. These prints, characterized by their dynamic compositions, expressive line, and complex, often enigmatic subject matter, reveal a mind deeply immersed in the classical tradition yet driven by a uniquely personal vision.

Influenced by the classical rigour of Domenichino and the intellectual depth of Nicolas Poussin, yet distinct from both, Testa carved out his own niche. His engagement with Cassiano dal Pozzo's "Paper Museum" sharpened his antiquarian knowledge, while his own melancholic temperament and philosophical inquiries imbued his work with a distinctive emotional intensity. Though his aspirations as a painter were largely unfulfilled in his lifetime, and his career was tragically cut short, his mastery of the etching needle secured him a lasting place. Pietro Testa stands as a testament to the artist as an intellectual, whose intricate visual meditations on mythology, allegory, and the human condition continue to challenge and reward the viewer, offering glimpses into a luminous mind often tinged with a somber, introspective hue.