Artemisia Gentileschi stands as one of the most compelling and significant figures of the Italian Baroque period. Born in Rome on July 8, 1593, and passing away in Naples between 1652 and 1654, she carved out an extraordinary career in an era overwhelmingly dominated by male artists. Her life was marked by profound personal trauma and professional challenges, yet she rose above adversity to produce a body of work characterized by its dramatic intensity, psychological depth, and a powerful, often assertive, portrayal of women. Her legacy, once obscured, has been rightfully re-evaluated, cementing her status not only as a preeminent painter of her time but also as a pivotal figure in the history of art and a beacon for feminist art historians.

Early Life and Artistic Apprenticeship in Rome

Artemisia was the eldest child and only daughter of Orazio Gentileschi, a respected Pisan-born painter who was himself influenced by the revolutionary naturalism of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. From a very young age, Artemisia was immersed in her father's workshop, learning to grind pigments, prepare canvases, and master the fundamentals of drawing and painting. It quickly became apparent that her talent far outstripped that of her brothers, who also trained under Orazio. Her father recognized her prodigious skill, and by her late teens, Artemisia was already contributing to his commissions and producing works of her own.

Her early style naturally absorbed the Caravaggesque tendencies prevalent in Rome at the time – the dramatic use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark), a commitment to realism, and a preference for depicting figures with palpable human emotion. Orazio, while a follower of Caravaggio, possessed a more lyrical and refined touch, which also informed Artemisia's developing aesthetic. However, even in her earliest works, a distinct and forceful artistic personality began to emerge, one that would soon be irrevocably shaped by a devastating event.

The Traumatic Turning Point: Agostino Tassi

In 1611, Orazio Gentileschi was collaborating on frescoes at the Palazzo Pallavicini-Rospigliosi in Rome with another painter, Agostino Tassi. Orazio entrusted Tassi, a specialist in perspective and illusionistic architecture, with the task of furthering Artemisia's instruction in perspective. Tragically, Tassi betrayed this trust and, in May 1611, raped the young Artemisia. When Tassi reneged on his promise to marry her (a common, albeit grim, way to "restore" a woman's honor at the time), Orazio pressed charges against him in 1612.

The ensuing seven-month trial was a public ordeal for Artemisia. She was subjected to humiliating gynecological examinations and even judicial torture – the sibille, thumbscrews – to "verify" her testimony, a common but brutal practice of the era. Despite the immense pressure and societal stigma, Artemisia courageously recounted the assault in detail. Her testimony, preserved in court records, reveals her strength and determination. Tassi was ultimately found guilty, though his sentence – a choice between five years' hard labor or banishment from Rome – was lenient and poorly enforced. He was, in fact, never truly punished, while Artemisia's reputation suffered grievously in the eyes of Roman society. This traumatic experience would profoundly influence her life and, arguably, the thematic content of her art.

A New Beginning in Florence: Independence and Recognition

Shortly after the trial concluded, in late 1612, Orazio arranged a marriage for Artemisia to Pierantonio Stiattesi, a minor Florentine artist. This union provided a means for Artemisia to leave Rome and the scandal behind, relocating to her husband's native Florence. This move marked a crucial turning point in her career, allowing her to establish herself as an independent artist. Florence, with its rich artistic heritage and influential patrons like the Medici family, offered new opportunities.

It was in Florence that Artemisia truly came into her own. She achieved a significant milestone in 1616 when she became the first woman admitted to the prestigious Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy of the Arts of Drawing), a testament to her recognized talent and ambition. This membership not only conferred professional status but also allowed her to buy paints and supplies without male permission and sign contracts in her own name. During her Florentine period (roughly 1613-1620), she cultivated relationships with influential figures, including Galileo Galilei, with whom she maintained a correspondence, and Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger (grandnephew of the great master), who became an important patron.

Her style in Florence evolved. While retaining the Caravaggesque drama, she absorbed some of the elegance and richer color palette characteristic of Florentine painting. She produced some of her most powerful and renowned works during this time, often focusing on strong female protagonists from biblical and mythological narratives.

Artistic Style: Caravaggism and a Unique Vision

Artemisia Gentileschi's art is inextricably linked to the Caravaggesque movement, yet she forged a style that was uniquely her own. From Caravaggio, she adopted the dramatic use of tenebrism, where figures emerge from deep shadow into stark light, creating a heightened sense of theatricality and emotional intensity. She also shared his commitment to naturalism, depicting figures with a raw, unidealized humanity. However, where Caravaggio's women could sometimes appear passive or objectified, Artemisia's female figures are often imbued with agency, strength, and complex psychological depth.

Her father, Orazio Gentileschi, also a follower of Caravaggio, influenced her with his more refined and elegant interpretation of Caravaggism, characterized by smoother brushwork and a richer, more varied palette than Caravaggio typically employed. Artemisia combined these influences, developing a style that was both dramatically potent and coloristically sophisticated. She excelled in rendering textures – a skill perhaps honed under Orazio – from gleaming silks and velvets to the metallic sheen of armor and the soft vulnerability of flesh.

What truly distinguishes Artemisia's work is her perspective, particularly in her depiction of female subjects. She brought an insider's understanding to their stories, often choosing moments of intense action, suffering, or triumph. Her heroines are not merely objects of the male gaze but active participants in their own narratives, displaying a range of emotions from vulnerability and fear to courage, determination, and righteous anger. This empathetic and often confrontational portrayal of women set her apart from most of her male contemporaries.

Key Themes and Subjects: Women of Power and Resilience

A recurring and defining feature of Artemisia Gentileschi's oeuvre is her focus on strong, often wronged, women from the Bible, mythology, and history. These subjects allowed her to explore themes of power, injustice, suffering, and retribution, often with a palpable personal resonance.

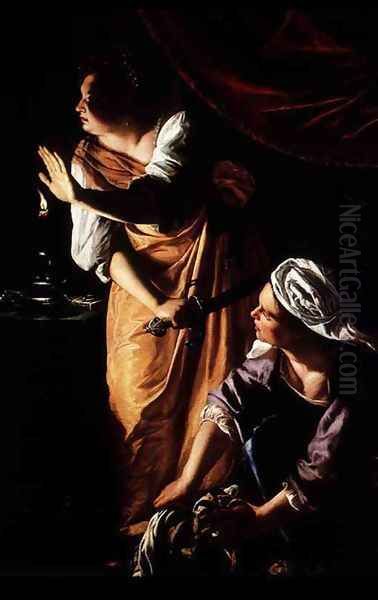

The story of Judith and Holofernes was one she returned to multiple times. Her most famous rendition, Judith Slaying Holofernes (c. 1614-20, Uffizi, Florence, and a later version c. 1620-21, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples), is a visceral and unflinching depiction of the biblical heroine beheading the Assyrian general. Unlike many male artists who portrayed Judith as either seductively beautiful or somewhat detached, Artemisia’s Judith is a figure of immense physical strength and grim determination, actively engaged in the violent act, her sleeves rolled up, her brow furrowed in concentration, as she and her maidservant Abra work together. Many scholars see a direct link between the raw power of these paintings and Artemisia's own experience of sexual violence and her subsequent fight for justice.

Susanna and the Elders was another theme she tackled early in her career (Susanna and the Elders, 1610, Schönborn Collection, Pommersfelden). Painted when she was just seventeen, it depicts Susanna in a state of acute distress and vulnerability as she recoils from the lecherous advances of the two elders. Artemisia’s portrayal emphasizes Susanna's revulsion and fear, a stark contrast to the often more voyeuristic or titillating interpretations by male artists.

Other powerful female figures in her repertoire include Lucretia, the Roman noblewoman who committed suicide after being raped (Lucretia, c. 1625-27, Getty Museum, Los Angeles); Cleopatra, the Egyptian queen, often depicted at the moment of her suicide (Cleopatra, c. 1621-22, Amedeo Morandorri Collection, Milan); and Jael, who slew the Canaanite general Sisera (Jael and Sisera, c. 1620, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest). She also painted numerous depictions of Mary Magdalene, often emphasizing her penitence and spiritual intensity, as in Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (c. 1623, private collection).

Masterpieces and Iconic Works

Artemisia Gentileschi's body of work includes several paintings that are now considered masterpieces of the Baroque era, celebrated for their technical skill, emotional power, and unique perspective.

Susanna and the Elders (1610): This early work, signed and dated when Artemisia was only seventeen, already showcases her remarkable talent. The composition is dynamic, with Susanna's contorted body expressing her distress as she tries to shield herself from the leering elders. The painting demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of anatomy and a nascent ability to convey complex emotion, setting the stage for her later, more overtly powerful heroines.

Judith Slaying Holofernes (c. 1614-20, Uffizi, Florence; and c. 1620-21, Naples): These are arguably her most iconic and impactful works. The Uffizi version, likely painted in Florence, is particularly brutal and direct. The intense physicality of the scene, the spurting blood, and the determined expressions of Judith and Abra are rendered with unflinching realism. Compared to Caravaggio's own version of the subject, Artemisia's Judith is more actively engaged and less ambivalent. The Naples version, painted slightly later, is even larger and perhaps more compositionally resolved, but retains the same visceral energy. These paintings are often seen as powerful statements of female agency and retribution.

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura) (c. 1638-39, Royal Collection, London): This ingenious self-portrait, likely painted during her time in London, depicts Artemisia in the act of painting. She embodies the allegorical figure of "Pittura" (Painting), identified by her unruly dark hair, gold chain with a mask pendant (symbolizing imitation), and richly colored, somewhat disheveled dress. The dynamic pose, with her arm outstretched towards an unseen canvas, and the intense concentration on her face, make this a powerful assertion of her identity as an artist. It cleverly subverts traditional allegorical representations by making the artist herself the embodiment of her art.

Esther before Ahasuerus (c. 1628-30, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): This large-scale history painting depicts the biblical Queen Esther fainting before King Ahasuerus as she pleads for the salvation of her people. The work showcases Artemisia's skill in handling complex multi-figure compositions and her ability to convey dramatic tension and emotional nuance. The rich colors and elaborate costumes reflect her evolving style.

Danaë (c. 1612, Saint Louis Art Museum): Though sometimes attributed to her father Orazio, many scholars now firmly attribute this sensual depiction of the mythological princess being visited by Zeus in a shower of gold to Artemisia. If by her, it demonstrates her early mastery of the female nude and her ability to imbue mythological scenes with a palpable sense of drama.

Other notable works include Judith and Her Maidservant (versions in Detroit Institute of Arts, c. 1625, and Palazzo Pitti, Florence), which often depict the tense moments after the beheading, and various depictions of the Madonna and Child, showcasing a more tender, though still strong, aspect of her artistic range.

A Pan-Italian and International Career: Travels and Patronage

After her successful period in Florence, Artemisia's career took her to various artistic centers across Italy and eventually to England. Around 1620, she returned to Rome, a city artistically vibrant but perhaps still holding difficult memories. Here, she navigated a competitive art world, associating with artists like Simon Vouet, a French painter who also embraced Caravaggism. Despite the challenges, she continued to receive commissions.

Financial difficulties and perhaps the desire for new opportunities led her to move to Venice for a brief period around 1627-1630. While less is known about her Venetian sojourn, the city's rich colorist tradition, exemplified by artists like Titian and Veronese (though from an earlier era, their influence persisted), may have further enriched her palette.

By 1630, Artemisia had settled in Naples, a bustling and artistically dynamic city under Spanish rule. Naples was a major center for Caravaggesque painting, with prominent artists like Jusepe de Ribera active there. She established a successful workshop and received numerous commissions for both private patrons and religious institutions. Her Neapolitan period was prolific, and she adapted her style to suit local tastes, sometimes producing larger, more complex altarpieces. It was during her Neapolitan years that she painted the Birth of St. John the Baptist for the Count of Monterrey, the Spanish viceroy.

In 1638, Artemisia traveled to London to join her father, Orazio, who had become a court painter to King Charles I. She assisted Orazio with the ceiling paintings for the Queen's House in Greenwich and also undertook independent commissions for the king and other members of the court. Her Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting dates from this English period. After Orazio's death in 1639, Artemisia remained in London for a few more years before returning to Naples, likely by 1641. She spent her final years in Naples, continuing to paint and run her workshop until her death.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Artemisia Gentileschi operated within a rich and competitive artistic landscape. Her primary influence was, of course, Caravaggio, whose revolutionary style swept through Rome and beyond. Her father, Orazio Gentileschi, was her first teacher and a significant Caravaggist in his own right.

In Rome, she would have been aware of other artists grappling with Caravaggio's legacy, such as Bartolomeo Manfredi, who popularized "Manfrediana methodus" (genre scenes of taverns, soldiers, and musicians in a Caravaggesque style), and later, French artists like Simon Vouet and Valentin de Boulogne. The more classicizing Bolognese school, led by Annibale Carracci and his followers like Guido Reni and Domenichino, offered an alternative to Caravaggism, emphasizing ideal beauty and balanced compositions, and their influence was also pervasive.

During her time in Florence, she interacted with local artists and patrons. In Naples, she was a contemporary of prominent painters like Jusepe de Ribera, a Spanish Caravaggist known for his stark realism, and Massimo Stanzione. The Neapolitan art scene was vibrant and demanding.

It is also important to place Artemisia within the context of other female artists of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, who, though fewer in number and often facing greater obstacles, made significant contributions. These include:

Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532–1625), a Cremonese artist renowned for her portraits, who achieved international fame and worked at the Spanish court.

Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614), a Bolognese painter who was highly successful, producing portraits, mythological scenes, and large-scale altarpieces. She is often cited as the first professional female artist in Western Europe who managed a large workshop and supported her family through her art.

Fede Galizia (1578–1630), a Milanese painter known for her pioneering still lifes and portraits.

Elisabetta Sirani (1638–1665), a Bolognese artist who, though younger than Artemisia, established a highly successful academy for female artists and was incredibly prolific before her untimely death.

Giovanna Garzoni (1600–1670), a contemporary of Artemisia, celebrated for her exquisite still life paintings, particularly watercolors on vellum.

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596-1676), a nun in Moncalvo, Piedmont, who painted religious works and distinctive still lifes, often featuring birds and flowers with symbolic meaning. (The provided text mentions "Orsola Martini," which might be a variant or less common name for Caccia, or a different, more obscure artist).

While direct interactions between all these women were not always possible due to geographical distances and societal constraints, their collective presence challenged the notion that art was an exclusively male domain. Artemisia's success, particularly her admission to the Florentine Accademia, was a significant step in this ongoing struggle for recognition.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Artemisia Gentileschi spent the last phase of her career in Naples, a city where she had established a strong professional footing. She continued to receive commissions and manage her workshop, adapting her style to the evolving tastes of the Neapolitan art market, which increasingly favored a more classical and less overtly dramatic Baroque aesthetic. Her later works sometimes show a lightening of her palette and a softening of her characteristic intensity, though her skill in composition and characterization remained evident. The exact date of her death is uncertain, but it is generally placed between 1652 and 1654, possibly during the devastating plague that struck Naples in 1656.

For centuries after her death, Artemisia Gentileschi's reputation languished. While never entirely forgotten, she was often relegated to the status of a minor follower of her father, or her work was sensationalized primarily through the lens of the Tassi rape trial. Her paintings were sometimes misattributed to Orazio or other male artists.

It was not until the 20th century, particularly with the rise of feminist art history in the 1970s, that Artemisia's work underwent a significant re-evaluation. Scholars like R. Ward Bissell and later Linda Nochlin (whose seminal 1971 essay "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" helped catalyze the field) and Mary D. Garrard (author of the groundbreaking 1989 monograph "Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art") were instrumental in restoring her to her rightful place. They meticulously researched her life, reattributed works, and analyzed her art through a new lens that acknowledged her gender and experiences.

Today, Artemisia Gentileschi is recognized as one of the most talented and progressive painters of her generation. Her ability to convey profound psychological depth, particularly in her portrayals of women, sets her apart. Her dramatic use of light and shadow, her bold compositions, and her often-confrontational subject matter continue to resonate with contemporary audiences. She is celebrated not only for her artistic achievements but also for her resilience in the face of immense personal and professional obstacles. Her life and work stand as a powerful testament to the enduring strength of the human spirit and the vital contributions of women to the history of art. Exhibitions of her work now draw large crowds, and her paintings are prized possessions of major museums worldwide, ensuring that her voice and vision will continue to inspire for generations to come.

Conclusion: A Baroque Master Reclaimed

Artemisia Gentileschi's journey from a talented young artist in her father's Roman workshop to an internationally recognized master is a story of extraordinary talent, fierce determination, and profound resilience. She navigated the treacherous waters of a male-dominated art world, overcame the trauma of sexual violence and public scandal, and forged an independent career that spanned Italy's major artistic centers and even reached the English court.

Her art, deeply influenced by Caravaggio yet uniquely her own, is characterized by its dramatic power, emotional intensity, and an unparalleled ability to depict strong, complex female protagonists. Through figures like Judith, Susanna, Lucretia, and Cleopatra, she explored themes of injustice, retribution, courage, and survival, often investing them with a palpable personal conviction. Her Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting stands as an iconic assertion of female artistic identity.

Once relegated to the footnotes of art history, Artemisia Gentileschi has been rightfully reclaimed as a pivotal figure of the Baroque period and a trailblazer for women artists. Her legacy endures not only in her breathtaking canvases but also in her inspiring story, which continues to captivate and empower. She was, without doubt, a true master, whose contributions have irrevocably enriched our understanding of art and the human experience.