Arthur Szyk stands as a unique figure in twentieth-century art, a master craftsman whose intricate, jewel-like creations served both aesthetic delight and fierce political engagement. Born in Poland and later becoming an American citizen, Szyk wielded his brush like a weapon, creating stunningly detailed book illustrations, powerful political caricatures, and masterful miniatures that drew inspiration from centuries of artistic tradition while confronting the urgent crises of his own time. His life spanned periods of intense upheaval – two World Wars, the rise of totalitarianism, and the Holocaust – events that profoundly shaped his worldview and fueled his artistic mission. He was an illustrator, a cartoonist, a miniaturist, a patriot, and an activist, leaving behind a legacy of visually dazzling works imbued with an unwavering commitment to justice, freedom, and human dignity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Arthur Szyk was born on June 16, 1894, in Łódź, Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. Łódź was a burgeoning industrial city, a melting pot of Polish, German, Jewish, and Russian cultures. Szyk grew up in a middle-class Jewish family; his father, Solomon Szyk, was a textile director. An anecdote sometimes recounted suggests his father suffered an eye injury from acid thrown during a workers' strike in 1905, an event that might have subtly influenced the young Szyk's awareness of social conflict, though its direct impact on his artistic path is speculative. What is certain is that Szyk displayed artistic talent from a young age.

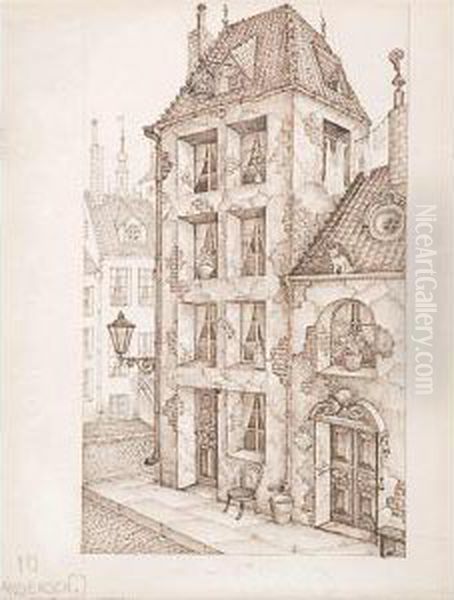

Recognizing his potential, his family supported his artistic inclinations. At the remarkably young age of fifteen, in 1909, Szyk traveled to Paris to study at the prestigious Académie Julian. This famous private art school had trained numerous influential artists, providing a fertile ground for young talent. Exposure to the vibrant Parisian art scene, which included Post-Impressionists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, and Fauvists like Henri Matisse, broadened his horizons, though Szyk's own path would diverge significantly from these modernist trends. He focused on drawing and painting, honing the meticulous skills that would become his hallmark. After his time in Paris, he continued his studies back in Poland, attending classes in Kraków, further immersing himself in European artistic traditions.

The Polish Patriot and Emerging Artist

Szyk's identity was complex, deeply rooted in both his Polish nationality and his Jewish heritage. He considered himself a Polish patriot and demonstrated this commitment early in his career. Following World War I and the re-establishment of an independent Poland, he served as a soldier and artistic director for the Department of Propaganda of the Polish army in Łódź during the Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921). This experience directly involved him in using art for political and nationalistic purposes, a role he would reprise on a larger scale later in his life.

During the 1920s, Szyk began to gain recognition for his distinctive style, particularly his revival of the art of manuscript illumination. A significant early project was his series of illuminations for the Statute of Kalisz, completed between 1926 and 1928. This historic thirteenth-century charter granted significant rights and protections to Jews in Poland. Szyk's lavish illustrations, rendered in a style reminiscent of medieval Gothic manuscripts with intricate borders and vibrant colors, celebrated this landmark document and the long history of Jewish life in Poland. The work was a testament to his dual loyalties and his belief in the possibility of Polish-Jewish coexistence and mutual respect. It was hailed as a masterpiece of modern illumination.

Parisian Interlude and International Recognition

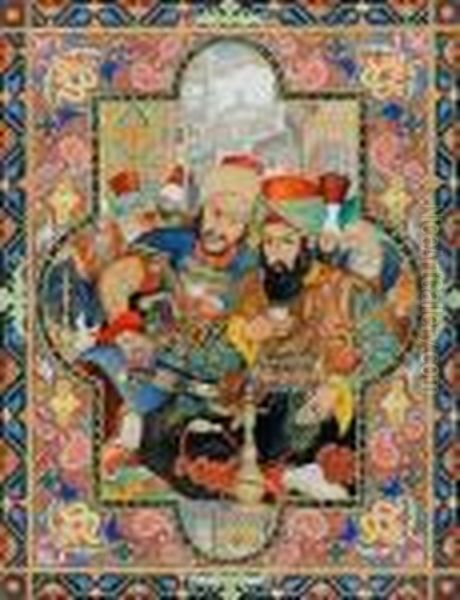

Szyk spent a significant portion of the 1920s and early 1930s living and working in Paris. This period was crucial for establishing his international reputation as a book illustrator and miniaturist. He immersed himself in the study of medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts, particularly French and Flemish traditions, as well as Persian miniature painting, absorbing their techniques of detailed rendering, rich color palettes, and complex compositions.

His exceptional skill quickly attracted commissions. He created illustrations for classic works of French literature, including Gustave Flaubert's The Temptation of Saint Anthony and Pierre Benoit's Jacob's Well (Le Puits de Jacob). His work was exhibited in Paris galleries and received critical acclaim. In 1923, the French government recognized his contributions to art and culture by awarding him the prestigious Ordre des Palmes Académiques. This period solidified his status as a leading figure in the revival of traditional illumination techniques, applied to both historical and literary subjects. His meticulous craftsmanship stood in stark contrast to the prevailing modernist movements, carving out a unique niche for his work.

The Shadow of Tyranny: Art as Weapon

The rise of Nazism in Germany and the growing threat of fascism across Europe profoundly impacted Szyk. As a Jew and a passionate advocate for democracy, he recognized the existential danger posed by these ideologies early on. His art began to shift decisively towards political commentary and satire. He saw his artistic talent not merely as a means of aesthetic expression but as a moral obligation to fight against tyranny.

In the late 1930s, anticipating the outbreak of war, Szyk moved his family first to London in 1937. There, he continued his work, most notably completing his monumental illustrations for the Haggadah, the Jewish text recited during the Passover Seder. Even this religious work carried contemporary political weight, with Szyk subtly casting the Egyptian Pharaoh as a precursor to modern tyrants like Hitler. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, his anti-Axis artwork became even more pointed and urgent. He held exhibitions in London, using his art to rally support for the Allied cause and expose the brutality of the Nazi regime.

The American Years: Propaganda and Patriotism

In late 1940, Szyk traveled to North America, initially to Canada and then settling in the United States, eventually becoming an American citizen in 1948. He arrived at a time when the US was still debating its involvement in the war. Szyk threw himself into the fight against isolationism, using his art as propaganda to galvanize American public opinion and support the Allied war effort. He famously declared himself a "soldier in art," dedicating his skills entirely to the fight against Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito.

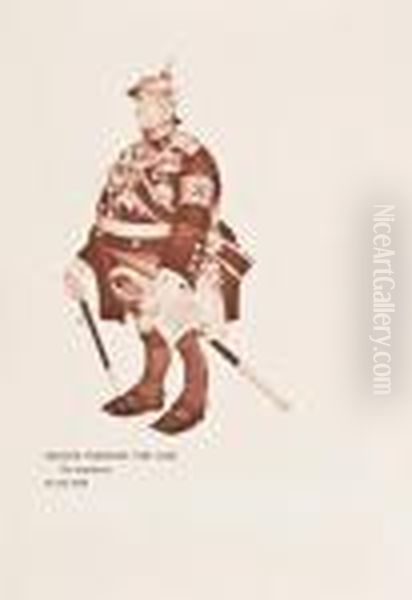

His political cartoons and illustrations became ubiquitous in America during the war years. They appeared on the covers and pages of major publications like Collier's, Esquire, Time, Look, Liberty, and the New York Post. His caricatures of Axis leaders were savage and unforgettable – depicting Hitler, Mussolini, Göring, Goebbels, and Hirohito as grotesque, demonic, or buffoonish figures, stripped of their propaganda-fueled grandeur and exposed as brutal tyrants. His style, combining meticulous detail with biting satire, was incredibly effective. Unlike the looser style of cartoonists like Britain's David Low or the G.I. perspective of America's Bill Mauldin, Szyk's work had the intensity and permanence of historical indictment rendered with the precision of a master illuminator.

His work was highly praised by figures like Eleanor Roosevelt and supported by government agencies. The Office of War Information utilized his drawings in leaflets dropped over enemy and occupied territories. Szyk produced posters, stamps, and advertisements supporting the military and war bonds. Two collections of his wartime drawings, The New Order (1941) and Ink & Blood (1946), showcased the power and fury of his anti-fascist art. He became one of the most prominent and effective propagandists for the Allied cause, his work seen by millions and contributing significantly to morale and resolve.

Masterpieces of Illumination: The Haggadah and Beyond

While his political cartoons gained widespread fame during the war, Szyk's reputation as a master illustrator rests significantly on his illuminated books, particularly the Szyk Haggadah. Completed over several years in the 1930s and finally published in London in 1940 on the eve of the Blitz, the Haggadah is widely considered one of the most beautiful books produced in the twentieth century and a pinnacle of modern manuscript illumination.

The Haggadah recounts the story of the Israelites' exodus from slavery in Egypt, a narrative central to Jewish identity and the Passover festival. Szyk poured his artistic genius and deep knowledge of Jewish history and tradition into its pages. Each page is a feast for the eyes, filled with vibrant colors, intricate borders inspired by medieval and Renaissance sources, and dynamic figure compositions. He masterfully blended traditional Jewish iconography with contemporary concerns. The suffering Israelites evoke the plight of Jews under Nazi persecution, while the tyrannical Pharaoh clearly parallels Adolf Hitler. The Haggadah became a powerful symbol of resistance and hope, a "Bible of Freedom" for a people facing annihilation. Its luxurious production, printed in multiple colors on vellum, further emphasized its status as a precious work of art.

Beyond the Haggadah, Szyk created stunning illustrations for numerous other books throughout his career. His early work on the Statute of Kalisz has already been noted. He also illustrated editions of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, The Book of Esther, Andersen's Fairy Tales, and Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. Each project showcased his versatility and his ability to adapt his style to different literary and historical contexts while maintaining his signature precision and richness. His approach to illumination rivaled the detail and complexity found in the work of historical masters like the Limbourg brothers (Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry) or Jean Fouquet, yet his interpretations were distinctly modern in their energy and often, their political undertones.

Artistic Style: A Fusion of Tradition and Modernity

Arthur Szyk's artistic style is immediately recognizable and remarkably consistent throughout his career, whether applied to religious texts, literary classics, or political satire. His primary medium was watercolor and gouache on paper or vellum, often combined with incredibly fine ink linework. He worked on a small scale, earning the title of miniaturist, yet his compositions are packed with detail, narrative complexity, and emotional intensity.

His influences were diverse but consciously chosen. He drew heavily from the traditions of medieval and Renaissance manuscript illumination, admiring their brilliant colors, decorative borders, flattened perspectives, and narrative clarity. The influence of Persian miniature painting is also evident in his intricate patterns, jewel-like colors, and stylized figures. While aware of modern art movements, he largely rejected abstraction and expressive distortion in favor of meticulous realism, albeit often heightened for dramatic or satirical effect. One might see echoes of the detailed portraiture and sharp observation of Northern Renaissance artists like Albrecht Dürer or Hans Holbein the Younger in his work's precision.

Szyk's genius lay in synthesizing these historical influences into a style that felt both timeless and urgently contemporary. He used rich, saturated colors, often employing gold and silver highlights reminiscent of medieval techniques. His compositions are typically dense, filling the entire picture plane with figures, architectural elements, and decorative motifs. Even in his political cartoons, where caricature was essential, the underlying draftsmanship remained incredibly detailed and controlled. This fusion of exquisite craftsmanship with powerful content gave his work a unique authority and impact.

Political Convictions and Activism

Arthur Szyk was fundamentally a political artist, driven by deeply held convictions. His primary targets were fascism, Nazism, and totalitarianism in all its forms. He saw the conflict of World War II not just as a clash of nations but as a battle for the soul of humanity, a struggle between democracy and barbarism. His art was his contribution to this struggle, a relentless exposé of Axis brutality and a celebration of Allied ideals, particularly those embodied by the United States and Great Britain.

His Jewish identity was central to his political consciousness. He was acutely aware of the rising tide of antisemitism in Europe and became a fierce advocate for his people. His wartime art consistently highlighted the specific persecution of Jews under the Nazis, seeking to awaken the conscience of the world. He was an early and vocal supporter of Zionism, believing that a Jewish state was necessary for the survival and self-determination of the Jewish people. He created artworks supporting the establishment of Israel, including illuminated versions of Israel's Declaration of Independence.

Szyk held strong democratic beliefs and admired the United States, seeing it as a beacon of freedom, despite his occasional criticisms of its policies. He actively campaigned against American isolationism before Pearl Harbor, believing that US intervention was crucial to defeating fascism. He collaborated with activist groups like the Bergson Group (the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe), led by Peter Bergson (Hillel Kook), which lobbied the US government to rescue European Jews during the Holocaust. Szyk provided powerful imagery for their campaigns. His commitment to human rights extended beyond Jewish concerns, encompassing a broader defense of liberty and dignity against oppression. However, his outspoken activism, particularly his association with groups deemed "left-leaning" or "Zionist," attracted suspicion during the Cold War era, leading to an investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) shortly before his death, though he was never formally charged.

Collaborations and Artistic Milieu

While Szyk was largely a singular figure stylistically, he operated within a network of publishers, political organizations, and fellow creatives. His move to the United States brought him into contact with the American media landscape, leading to his prolific work for magazines and newspapers. His relationship with publishers was crucial for disseminating his book illustrations and political art collections.

A notable collaboration was with the fiery Hollywood screenwriter and activist Ben Hecht. Szyk provided illustrations for some of Hecht's impassioned writings advocating for Jewish rescue and resistance, such as "The Ballad of the Doomed Jews of Europe." Both men shared a sense of outrage and urgency regarding the Holocaust and used their respective talents to try and spur action.

Szyk can be situated within the broader context of émigré artists who fled European fascism and contributed to American culture and the Allied war effort. Figures like the German satirist George Grosz also brought a sharp critical eye to their new home, though Grosz's style was rougher and more expressionistic. The photomontage artist John Heartfield, another anti-Nazi German émigré (though primarily active in Europe), used visual manipulation for political ends, contrasting with Szyk's handcrafted approach. While Szyk's detailed narrative style differs greatly from the broad storytelling of American illustrators like N.C. Wyeth or Howard Pyle, he shared their commitment to visual narrative. Similarly, while stylistically distinct from contemporary European Jewish artists like Marc Chagall or Chaim Soutine, Szyk shared their experience of displacement and the shadow of persecution, channeling it into his unique artistic vision.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

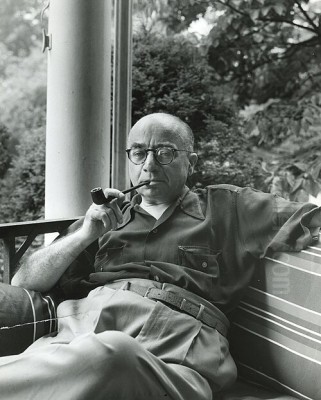

Arthur Szyk died relatively young, suffering a heart attack at his home in New Canaan, Connecticut, on September 13, 1951, at the age of 57. He left behind a prolific and powerful body of work that continues to resonate. For a period after his death, his fame somewhat faded, overshadowed by the rise of Abstract Expressionism and other modernist trends that seemed far removed from his meticulous, representational style.

However, in recent decades, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in Szyk's art. Scholars, curators, and collectors have recognized the unique power of his work, its historical significance, and its enduring relevance. The Arthur Szyk Society was established to promote his legacy, and major exhibitions have been mounted at prominent institutions, including the New-York Historical Society, the Library of Congress, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life at UC Berkeley, and the National WWII Museum in New Orleans. These exhibitions have reintroduced his art to new generations, highlighting both his exquisite craftsmanship and his passionate engagement with the defining issues of his time.

Szyk's legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as one of the foremost modern practitioners of manuscript illumination, breathing new life into an ancient art form. He stands as one of the most important political artists of the twentieth century, whose work served as a potent weapon against fascism and a powerful testament to the resilience of the human spirit. His art provides invaluable historical documentation of World War II, the Holocaust, and the fight for Jewish statehood. Perhaps most importantly, his work continues to inspire artists who seek to combine aesthetic beauty with social conscience, such as graphic novelist Art Spiegelman, whose work Maus also grapples with Holocaust memory through visual narrative. Arthur Szyk remains a compelling figure whose art reminds us of the power of visual imagery to illuminate history, challenge injustice, and champion human dignity.