Astley David Middleton Cooper stands as a fascinating, prolific, and sometimes controversial figure in the landscape of American art, particularly renowned for his depictions of the American West during a period of profound transformation. An American painter by nationality, Cooper's long career spanned the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, leaving behind a vast body of work that captured Native American life, dramatic landscapes, historical events, and portraits, often filtered through a romantic lens. His life and art offer a window into the artistic tastes, cultural mythologies, and social dynamics of California and the broader American West during his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, on December 22, 1856, Astley David Middleton Cooper, often known as A.D.M. Cooper, entered a world brimming with westward expansion narratives. His family background provided unique connections to this theme. His father, David Middleton Cooper, was a respected physician of Irish descent. His mother, Fannie Clark O'Fallon, hailed from a prominent lineage, being a niece of William Clark, the famed explorer of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. This familial link to one of America's foundational exploration stories likely played a role in shaping young Cooper's interests.

His early exposure to art and the West was further solidified through family connections. George Catlin, the pioneering painter known for his extensive documentation of Plains Indian tribes in the 1830s, was reportedly a friend of the Cooper family. Catlin's vivid paintings and perhaps his personal stories are believed to have ignited Cooper's lifelong fascination with Native American cultures, providing an early and powerful artistic influence. This inspiration set him on a path distinct from many academic painters of his era.

Cooper received his formal art training locally at Washington University in St. Louis. While details of his specific instructors are scarce, the environment would have exposed him to prevailing academic standards. However, his true passion lay beyond the confines of the studio. Driven by a desire to witness firsthand the subjects that captivated him, Cooper embarked on travels westward, seeking direct experience with the landscapes and peoples of the American frontier.

Journey West and Early Career

In the early 1870s, seeking adventure and artistic subjects, Cooper ventured west. His travels took him through territories that were rapidly changing, offering glimpses of Native American life that was increasingly under pressure from settlement and government policies. He spent time living among various tribes, sketching and gathering impressions that would inform his work for decades. This period of immersion, reminiscent of the approach taken by George Catlin decades earlier, provided him with authentic details, even if his later paintings often employed a significant degree of romantic idealization.

A significant stop during this formative period was Boulder, Colorado. For approximately two years, Cooper honed his skills as an illustrator, working for the popular publication Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. This experience likely sharpened his narrative abilities and his capacity to produce work quickly, traits that would characterize his later career. Periodicals like Leslie's and Harper's Weekly were crucial disseminators of images of the West, employing artists like Cooper, and others such as Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell who also started in illustration, to bring distant scenes to an eager eastern audience.

By the late 1870s or early 1880s, Cooper had made his way to California, initially spending time in San Francisco, the burgeoning cultural hub of the West Coast. The city boasted a lively arts scene, with established figures like landscape painters William Keith and Thomas Hill dominating the market, and bohemian artists like Jules Tavernier adding a different flavor. Cooper eventually settled further south in the Santa Clara Valley, establishing his primary residence and studio in San Jose around 1882. This move marked the beginning of his most productive and locally famous period.

The San Jose Studio and Persona

In San Jose, Cooper cultivated a distinct artistic persona and environment. He constructed a large, eccentric studio adjacent to his home, designed in a striking Egyptian Revival style. This architectural choice was itself a statement, reflecting a taste for the exotic and historical that sometimes surfaced in his work. The studio became a local landmark and a reflection of Cooper's flamboyant personality. It was reportedly filled with an eclectic mix of Native American artifacts, pioneer relics, artistic props, and even, according to some accounts, Egyptian mummies, creating an atmosphere that was part museum, part stage set.

Cooper himself was known as a bon vivant, a man of considerable charm, culture, and generosity. He was a prominent figure in San Jose's social life, known for his hospitality, his enjoyment of fine food and drink, and his engaging storytelling. He frequented local saloons and restaurants, sometimes using his paintings, particularly smaller works or studies, to settle bar tabs. This practice, especially when involving his controversial nude paintings, contributed to his somewhat bohemian reputation and occasionally drew criticism from more conservative elements of society.

Despite this reputation, Cooper was also described as courteous and well-read. His lifestyle, while perhaps unconventional for the time, seemed intertwined with his artistic identity. The studio was not just a place of work but also a space for entertaining and reinforcing his image as a successful, worldly artist deeply connected to the spirit of the West. His commercial success allowed him to maintain this lifestyle, making him one of the most financially successful artists in the region during his lifetime.

Artistic Style and Influences

A.D.M. Cooper's artistic style evolved throughout his career but consistently blended observation with a strong sense of romanticism and narrative drama. His primary influence, George Catlin, is evident in his choice of subject matter – the focus on Native American life and culture. However, Cooper's approach differed significantly. While Catlin aimed for a more ethnographic record (though still shaped by his own perspective), Cooper often prioritized dramatic effect, storytelling, and idealized beauty.

His earlier works often show tighter brushwork and a more detailed finish, aligning with the academic training he received. Many of his paintings, particularly landscapes and scenes featuring Native Americans, exhibit characteristics associated with Tonalism, a style popular in the late 19th century championed by artists like George Inness and James McNeill Whistler. This is seen in his use of muted color palettes, soft atmospheric effects, and an emphasis on mood, often depicting scenes at dawn, dusk, or under moonlight to enhance their evocative quality.

However, Cooper's Tonalism was often infused with more dynamism and narrative content than typical for the style. His compositions frequently feature active figures, dramatic lighting, and a sense of unfolding events. He was adept at capturing the movement of horses and the intensity of human expressions, lending his historical and Native American scenes a theatrical quality. This romantic inclination aligns him broadly with earlier painters of the West like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran, who emphasized the sublime and dramatic aspects of the landscape and its inhabitants, though Cooper's scale was generally more intimate.

In his later years, Cooper's style sometimes loosened, incorporating brighter colors and more visible brushstrokes, suggesting an awareness of Impressionism. This is particularly noticeable in some of his landscapes. However, he never fully embraced Impressionism's focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and color, retaining his commitment to narrative subjects and a fundamentally romantic worldview. His versatility allowed him to tackle various genres, from detailed portraits to expansive historical compositions.

Themes and Subjects

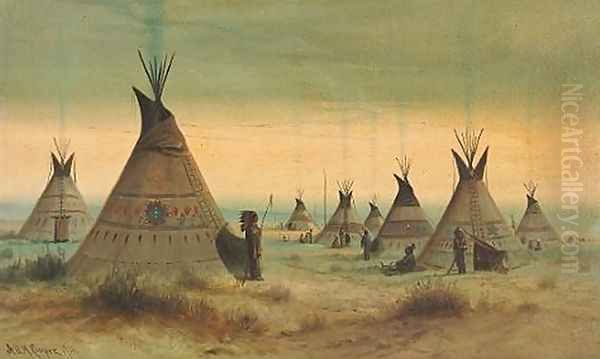

The most prominent theme throughout Cooper's extensive oeuvre is the depiction of Native American life. He painted numerous scenes of Plains Indian tribes – Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, Crow, Blackfeet – often shown in traditional activities: hunting buffalo, engaging in council meetings, participating in ceremonies, or involved in conflict. These works, while rich in detail regarding attire and accoutrements, often present an idealized and romanticized vision of Native American existence, sometimes emphasizing nobility and harmony with nature, and other times focusing on dramatic moments of warfare or ritual.

Cooper's interest extended beyond the Plains tribes to include California's Native peoples as well, though his most famous works tend to feature the more widely recognized Plains cultures. His depictions occurred during a period of intense conflict, displacement, and forced assimilation for Native Americans across the West. While his paintings brought visibility to these cultures, modern perspectives often critique them for perpetuating stereotypes or glossing over the harsh realities faced by Native communities. His work contrasts with the more localized, intimate, and arguably more sensitive portrayals of California's Pomo people by his near-contemporary, Grace Hudson.

Landscapes formed another significant part of Cooper's output. He painted the diverse scenery of the American West, from the Rocky Mountains of Colorado and Montana to the coastal ranges and valleys of California. These landscapes often served as dramatic backdrops for his narrative scenes but were also subjects in their own right, rendered with the atmospheric sensitivity characteristic of his Tonalist leanings.

Historical scenes were also a recurring subject. One notable example is his depiction of the ill-fated Donner Party, a harrowing episode from California's pioneer history. Such works tapped into the public fascination with the dramatic and often tragic stories of westward expansion. He also painted portraits of prominent local figures and pioneers, fulfilling commissions that contributed to his financial success.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of his subject matter was his paintings of female nudes. Often classical or allegorical in theme (e.g., Venus), these works were sometimes displayed or sold in less conventional venues, such as saloons. While reflecting a tradition within Western art, their association with Cooper's bohemian lifestyle and their use in trade for drinks caused friction with some patrons and contributed to debates about the propriety of his art and conduct.

Major Works

Identifying specific "major works" from an artist as prolific as Cooper, who reportedly created thousands of paintings, can be challenging. However, several paintings are frequently cited as representative of his style and themes.

Burning Arrow (c. 1876-77): This early and dramatic work depicts Sioux warriors using flaming arrows, possibly as signals, during the Great Sioux War. It exemplifies Cooper's flair for action, dramatic lighting (the glow of the fire against the night sky), and detailed rendering of Native American figures and attire. It captures the tension and conflict associated with the period.

Landscape at Eagle Peak, Montana, with meeting of Lakota, Sioux, and Cheyenne Warriors (1921): This later work showcases Cooper's continued engagement with Native American themes and his landscape skills. The painting depicts a council or meeting between warriors from different tribes against a majestic mountain backdrop. It reflects the romantic notion of intertribal alliances and the grandeur of the Western landscape, painted with a somewhat looser, more atmospheric touch characteristic of his later style.

The Last Stand Theme: Cooper painted several works that tapped into the popular "Last Stand" motif, famously associated with Custer's defeat but applied more broadly to depict heroic, doomed resistance by both soldiers and Native Americans. These paintings, often filled with dramatic action and pathos, contributed to the mythology of the West as a place of epic struggle and sacrifice. While perhaps not a single iconic painting, this recurring theme was central to his appeal and his role in shaping popular imagery, similar to how artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell explored themes of conflict and the closing frontier.

Saloon Nudes: Though specific titles like Venus are sometimes mentioned, the collective body of Cooper's nude paintings, often created for or displayed in saloons and private clubs, represents a distinct and controversial aspect of his work. These paintings, while perhaps less central to his artistic reputation today, were well-known during his lifetime and contributed significantly to his notoriety and his complex relationship with patrons and the public.

Donner Party Paintings: His depictions of the tragic Donner Party saga, focusing on the suffering and desperation of the snowbound pioneers, were powerful historical narratives that resonated with California audiences familiar with the story. These works highlighted his ability to convey intense human emotion and historical drama.

Cooper and His Contemporaries

Placing A.D.M. Cooper within the context of his contemporaries reveals his unique position. He operated somewhat outside the mainstream East Coast art establishment, yet engaged with national trends like Tonalism and the widespread fascination with the West.

His most direct artistic lineage traces back to George Catlin, whose work provided the initial spark. However, Cooper's romantic and often dramatic style aligns him more closely with the generation of Western artists who followed Catlin, including Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran. These artists, associated with the Hudson River School's second generation, brought a European-influenced grandeur and romanticism to Western landscapes and Native American subjects. Cooper shared their penchant for dramatic compositions and atmospheric effects, though his work was often on a smaller scale and focused more frequently on human figures and narrative.

In the realm of Western narrative art and illustration, Cooper's career overlapped significantly with Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell. While Cooper shared their interest in cowboys, soldiers, and Native Americans, his style remained distinct. Remington developed a more vigorous, almost impressionistic realism, particularly in his bronzes and later paintings, while Russell became known for his detailed, narrative accuracy and deep empathy for the cowboy way of life. Cooper's work, by contrast, often retained a softer, more Tonalist or classically romantic feel.

Within the California art scene, Cooper was a contemporary of figures like William Keith, the dominant landscape painter known for his moody, Barbizon-influenced scenes, and Thomas Hill, famous for his grand depictions of Yosemite. Cooper's focus on narrative and Native American subjects differentiated him from these landscape specialists. He also coexisted with San Francisco Bohemians like Jules Tavernier, who shared a certain flamboyant lifestyle but whose art often explored different themes. Compared to Grace Hudson, who focused meticulously on the Pomo people of Northern California with ethnographic detail and personal connection, Cooper's Native American paintings appear more generalized and romanticized. Early California artists like Charles Christian Nahl, known for historical and genre scenes, set a precedent for narrative painting in the state that Cooper continued.

His connection to Tonalism links him to painters like George Inness and James McNeill Whistler, though Cooper's application of Tonalist principles was often blended with stronger narrative elements. His occasional use of historical or exotic themes might even distantly echo the academic precision and exoticism of European painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose work was widely known through reproductions. Cooper synthesized these various influences into a style that was distinctly his own, tailored to his subjects and his market.

Commercial Success and Prolific Output

One of the defining characteristics of Cooper's career was his remarkable productivity and commercial success. Estimates of his lifetime output range widely, from over a thousand paintings to as many as ten thousand. While the higher figure may be an exaggeration, there is no doubt that he was an exceptionally prolific artist. This high volume was partly driven by demand; Cooper found a ready market for his work, particularly among Californians interested in depictions of the state's history, landscapes, and the romanticized image of the vanishing West.

His paintings were acquired by prominent figures, including politicians, businessmen, and collectors. Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University, was reportedly an admirer and patron. Cooper's work adorned homes, hotels, restaurants, and saloons throughout the Santa Clara Valley and beyond. His ability to work relatively quickly and in various sizes, from large canvases to small studies suitable for quick sale or trade, contributed to his financial independence.

This commercial success and high output, however, also led to criticism, both during his lifetime and subsequently. Some critics questioned the artistic merit and consistency of such a vast body of work, suggesting that the pressure to produce quantity might have sometimes compromised quality or led to repetition. His willingness to paint popular, easily digestible themes, and even trade art for services or goods, positioned him as a highly commercial artist, sometimes viewed with suspicion by those who valued artistic purity over market appeal. Nevertheless, his success undeniable made him a major figure in the regional art market of his time.

Controversies and Criticisms

A.D.M. Cooper's career was not without controversy. His depictions of Native Americans, while popular, have faced scrutiny for their romanticization and potential historical inaccuracies. Painting during an era marked by the subjugation of Native peoples, his idealized images often presented a nostalgic view of a "vanishing race," which, while perhaps sympathetic in intent, could also serve to obscure the violent realities of conquest and displacement. His work participated in the creation of the "Myth of the West," a powerful cultural narrative that often prioritized adventure and romance over historical complexity.

The "Last Stand" theme, popular in Cooper's work and that of his contemporaries, further contributed to this mythology, often focusing on heroic defiance in the face of overwhelming odds, whether by soldiers or warriors. While compelling narratives, these depictions could simplify complex historical events and reinforce stereotypes.

His personal life and business practices also generated controversy. His bohemian lifestyle, particularly his association with saloons and the reported use of nude paintings to pay debts, clashed with the Victorian sensibilities of some potential patrons among the social elite. While admired for his charm and generosity, his reputation for indulgence sometimes overshadowed his artistic accomplishments in the eyes of critics.

Furthermore, the sheer volume of his output led to questions about authenticity and quality control. Like many prolific artists, he likely employed studio assistants or repeated successful formulas, leading to variations in the quality of works attributed to him. The market success itself could be seen critically, suggesting an artist perhaps too willing to cater to popular taste rather than pursuing a more challenging artistic vision.

Later Life and Legacy

Cooper continued to paint actively into the early 20th century. In 1919, at the age of 63, he married for the first and only time. His bride was Edith M. Field, the daughter of a family friend, and significantly younger than him (reportedly by 26 years). The marriage, however, was relatively short-lived, lasting less than five years until Cooper's death.

Astley David Middleton Cooper passed away in San Jose, California, on September 10, 1924, at the age of 67. He left behind a complex legacy. During his lifetime, he was one of Northern California's most recognized and commercially successful artists, celebrated for his depictions of the West and his engaging personality. His work helped shape the popular imagination of Native American life and the frontier era for many Californians.

After his death, his reputation experienced fluctuations common to many artists whose styles fall out of fashion. The romanticism and narrative focus of his work were less valued during the rise of Modernism. However, renewed interest in American Western art and regional art histories has brought his work back into consideration. Today, his paintings are held in numerous private collections and public institutions, including the Autry Museum of the American West, the Gilcrease Museum, the Crocker Art Museum, and various historical societies and museums in California, particularly in the San Jose area.

His legacy remains multifaceted. He was a skilled painter capable of capturing mood, drama, and detail. He was a significant chronicler, albeit through a romantic filter, of Native American cultures and Western history during a critical period. He was also a highly successful commercial artist who understood his market and cultivated a memorable public persona. While subject to valid criticisms regarding historical accuracy and romanticization, A.D.M. Cooper's vast body of work provides invaluable insight into the art, culture, and mythology of the American West at the turn of the twentieth century.

Conclusion

Astley David Middleton Cooper navigated the artistic currents of his time with remarkable success, creating a vast and varied body of work centered on the American West. From his St. Louis roots and familial connection to exploration, through his formative travels and eventual establishment as a major figure in the California art scene, Cooper crafted a career marked by prolific output, commercial acumen, and a distinctive romantic style. Influenced by artists like George Catlin but developing his own blend of Tonalism, narrative drama, and idealized representation, he captured landscapes, historical moments, and particularly the lives of Native Americans, contributing significantly to the visual mythology of the frontier.

While his romanticized depictions and controversial lifestyle drew criticism, his skill as a painter and his ability to connect with a broad audience cemented his importance during his lifetime. Today, his work invites ongoing discussion about the representation of history, the role of the artist in shaping cultural narratives, and the complex interplay between art, commerce, and personal reputation. A.D.M. Cooper remains a key figure for understanding the art and popular imagination of the American West in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.