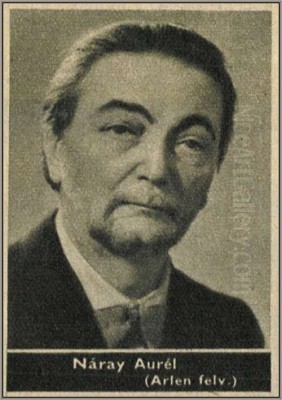

Aurel Náray (1883-1948) remains a somewhat enigmatic figure in the broader narrative of early 20th-century Hungarian art. While not as widely celebrated as some of his contemporaries who spearheaded avant-garde movements or achieved international renown, Náray's work, particularly his religious paintings, offers a window into a persistent strand of artistic expression that valued traditional themes and meticulous execution. His life spanned a tumultuous period in European history, witnessing the final decades of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the upheaval of two World Wars, and significant shifts in artistic paradigms. Understanding Náray requires piecing together the sparse details of his life with the context of the rich and complex artistic environment of Hungary during his active years.

Biographical Scantlings and the Hungarian Context

Born in 1883, Aurel Náray came of age during a vibrant period for Hungarian arts and culture. Budapest, by the turn of the century, was a burgeoning metropolis, often called the "Paris of the East," and a crucible for artistic innovation, though traditional academic art still held considerable sway. Information regarding Náray's specific birthplace, upbringing, and formal artistic training is not extensively documented in readily accessible international sources. This is not uncommon for artists who may have primarily operated within a national or regional sphere, or whose estates were not managed in a way that promoted international scholarly attention after their passing in 1948.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries in Hungary saw artists grappling with questions of national identity, absorbing influences from major European art centers like Munich, Vienna, and Paris, and forging unique local responses. Figures like Mihály Munkácsy (1844-1900) had already achieved international fame with his dramatic realism, setting a high bar for Hungarian painters. Academic training, often pursued at the Hungarian Royal Drawing School (later the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts) in Budapest or at academies in Munich or Vienna, would have been a likely path for an aspiring artist of Náray's generation.

The Artistic Milieu: Tradition and Modernity

The Hungarian art scene during Náray's formative and productive years was diverse. While academic realism and historicism, championed by artists like Gyula Benczúr (1844-1920) and Károly Lotz (1833-1904) with their grand historical canvases and murals, continued to be influential, new currents were emerging. The Nagybánya artists' colony, founded in 1896 by Simon Hollósy, Károly Ferenczy, Béla Iványi-Grünwald, István Réti, and János Thorma, introduced plein-air painting and influences from French Naturalism and Impressionism, profoundly impacting Hungarian art.

Simultaneously, Symbolism and Art Nouveau (Szecesszió in Hungarian) found fertile ground. Artists like József Rippl-Rónai (1861-1927), who had connections with the Parisian Nabis group, and Lajos Gulácsy (1882-1932), with his dreamlike, melancholic visions, represented these trends. The unique, almost visionary Symbolist painter Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka (1853-1919) also created his most significant works during this period, though he remained largely an outsider. Later, avant-garde movements like Expressionism and Constructivism would also make their mark, with figures such as Lajos Kassák (1887-1967) becoming central to the Hungarian avant-garde.

Náray's Known Oeuvre: A Focus on Religious Art

The most concretely documented aspect of Aurel Náray's artistic output centers on his religious paintings. One such work, reportedly depicting the "Madonna and Child" or, more specifically identified in some sources as "Saint Joseph and the Infant Jesus," is dated to 1909. This oil painting, measuring approximately 42.5 x 57 cm (or 42 x 57.5 cm), is known to be in a private collection and bears the artist's signature and the date "Aurel Náray 909." The existence of this piece, and its subsequent need for restoration due to issues like minor canvas damage and frame warping, underscores its perceived value to its owners.

The choice of religious subject matter in 1909 places Náray within a long tradition, but also at a time when such themes were being reinterpreted or sometimes eschewed by more radical modernists. However, religious art continued to be commissioned and appreciated, particularly for devotional purposes or for ecclesiastical settings. Artists like the Danish Joakim Skovgaard (1856-1933) or the French Symbolist Maurice Denis (1870-1943), a contemporary of Rippl-Rónai in the Nabis, were also known for their significant contributions to modern religious art, demonstrating that the genre was far from moribund.

Artistic Style: Detail, Color, and Devotion

Based on descriptions, Náray's style in his religious works is characterized by a dedication to fine detail and a considered use of color. The mention of "light and shadow contrast to enhance depth and dynamism" suggests an artist skilled in academic techniques, capable of creating a sense of volume and atmosphere. Such an approach would align with a more traditional, perhaps realistic or subtly idealized, representation of sacred figures, aiming to evoke reverence and piety.

If his "Saint Joseph and the Infant Jesus" from 1909 is representative, Náray's early style would likely have been grounded in the academic training prevalent at the time, possibly with influences from late Romanticism or a gentle form of Symbolism that often infused religious subjects with emotional depth. The intimacy of a scene like St. Joseph with the infant Christ lends itself to a tender, humanizing portrayal, a common characteristic in devotional art intended for private contemplation.

There is a suggestion in the provided information that Náray's work might have shifted "from an early romantic style gradually towards a colder and more severe style" around the 1940s. Given his death in 1948, this would represent a late-career development. Without more visual evidence or scholarly analysis of works from this later period, it is difficult to elaborate extensively on this potential stylistic evolution. However, such a shift could reflect broader cultural changes, personal artistic development, or the somber mood prevalent during and after World War II. The "colder, more severe style" might imply a move towards greater simplification, a more austere palette, or a more monumental, less sentimental approach to form, perhaps echoing neo-classical or even certain modernist tendencies that stripped away ornamentation.

The mention of "attention to detail in urban scenes" is intriguing but less substantiated in the context of his known religious works. If Náray did indeed paint urban scenes, it would broaden our understanding of his thematic range, placing him alongside other Hungarian artists who depicted the changing face of Budapest, such as János Vaszary (1867-1939) in some of his phases, or the earlier veduta painters.

Contemporaries and Potential Influences

While direct records of Náray's interactions with other artists are scarce, he worked within a vibrant artistic community. Besides the aforementioned Hungarian masters, one could consider the broader European context. The Munich Academy, a major training ground for many Central and Eastern European artists, including Hungarians like Sándor Liezen-Mayer (1839-1899) in an earlier generation, emphasized strong draughtsmanship and a polished finish. If Náray studied there, or was influenced by its graduates, this would be reflected in his technique.

The spiritual and symbolic dimensions of art were being explored across Europe. The Pre-Raphaelites in Britain, though earlier, had revived religious themes with intense detail and emotional sincerity. In France, artists like Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898) created serene, allegorical murals that had a wide impact. In the German-speaking world, artists like Fritz von Uhde (1848-1911) brought a new naturalism to biblical scenes, often placing them in contemporary settings. While it's speculative to draw direct lines of influence without more specific biographical data, Náray would have been aware of these broader trends through art journals, exhibitions, and word of mouth.

His Hungarian contemporaries who also engaged with religious or symbolic themes, albeit in diverse styles, include Aladár Körösfői-Kriesch (1863-1920), a key figure in the Gödöllő artists' colony which blended Art Nouveau with Hungarian folk traditions and spiritual concerns. The deeply personal and often melancholic landscapes and figure paintings of László Mednyánszky (1852-1919), while not strictly religious, often carried a profound spiritual weight.

Legacy and Collection

Aurel Náray's works, as indicated, are primarily found in private collections. This situation, while not diminishing the intrinsic artistic merit of his paintings, does limit their public visibility and accessibility for scholarly study. The fact that a piece like "Saint Joseph and the Infant Jesus" has been preserved and deemed worthy of restoration speaks to a continued appreciation by its custodians.

The absence of his works in major public museum collections (or at least, their lack of prominence in easily searchable databases) contributes to his relative obscurity on the international stage. However, many competent and significant artists often remain primarily known within their national or regional contexts, their contributions forming an essential part of the rich tapestry of local art history.

The art market occasionally sees works by lesser-known artists from this period surface, and it is possible that more of Náray's oeuvre exists, awaiting rediscovery or further research. Cataloging and researching artists like Náray is crucial for a more complete understanding of the diverse artistic production of a period, moving beyond the headline names to appreciate the full spectrum of creative endeavor.

Conclusion: An Artist of Quiet Devotion

Aurel Náray emerges from the available information as a Hungarian painter dedicated to his craft, with a particular focus on religious themes rendered with technical skill and attention to detail. Active in the first half of the 20th century, his 1909 painting of "Saint Joseph and the Infant Jesus" provides a tangible example of his work, aligning with traditional devotional art while being a product of its specific time and cultural milieu.

While he may not have been at the forefront of the avant-garde movements that were reshaping European art, Náray represents an important aspect of artistic practice: the continuation and sensitive interpretation of established genres. His work, characterized by its careful execution and sincere religious sentiment, offers a quiet counterpoint to the more radical artistic experiments of his era. Further research, particularly within Hungarian art historical archives and private collections, might yet illuminate more facets of Aurel Náray's life and artistic journey, allowing for a more comprehensive appreciation of his place within the story of Hungarian art. His legacy, though modest in terms of global recognition, is a reminder of the many artists whose dedication contributes to the richness and diversity of cultural heritage.