Francesco de' Rossi, more famously known by the moniker Il Salviati, or sometimes Cecchino Salviati, stands as a pivotal figure in the complex and often dazzling artistic landscape of 16th-century Italy. Born in Florence in 1510, he emerged during a period of profound artistic transition, as the High Renaissance ideals of harmony and naturalism, epitomized by giants like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and the early Michelangelo, began to give way to a new, more stylized, and intellectually sophisticated mode of expression: Mannerism. Salviati's career, which spanned across key artistic centers including Florence, Rome, Venice, and even a period in France, showcases a remarkable adaptability and a restless creative energy that defined him as one of Mannerism's most accomplished and versatile proponents. His oeuvre, encompassing grand frescoes, elegant panel paintings, insightful portraits, and intricate designs for tapestries and other decorative arts, reflects the era's taste for virtuosity, complexity, and refined artifice.

Early Life and Florentine Apprenticeship

Francesco de' Rossi was born into a Florence still basking in the afterglow of its High Renaissance glory but already feeling the stirrings of change. His father, Michelangelo de' Rossi, was a weaver of velvets, a respectable artisan trade in a city renowned for its luxury textiles. This background, while not directly artistic in the painterly sense, would have exposed young Francesco to a world of intricate patterns, rich colors, and skilled craftsmanship, elements that would later subtly inform his own meticulous attention to detail and decorative richness.

His formal artistic training began under Giuliano Bugiardini, a competent painter who had himself been associated with Michelangelo. However, Salviati's ambition and talent soon led him to seek out more stimulating environments. He subsequently worked with Baccio Bandinelli, a sculptor and painter known for his strong, Michelangelesque figures and a somewhat contentious personality. Perhaps the most formative influence during these early years was his time in the workshop of Andrea del Sarto, one of Florence's leading painters in the early 16th century. Del Sarto, known as the "faultless painter," was celebrated for his harmonious compositions, sfumato, and rich color palette. In del Sarto's studio, Salviati would have worked alongside other talented young artists who would also make their mark, such as Jacopo Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, both of whom became leading figures in the early development of Florentine Mannerism. It was also during this period, around 1529, that he formed a close and lasting friendship with Giorgio Vasari, the painter, architect, and art historian whose Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects remains a primary source for our understanding of Renaissance and Mannerist art, including Salviati's own career.

The Roman Crucible and the Salviati Name

Around 1531, seeking broader opportunities and exposure to the monumental art of antiquity and the High Renaissance masters, Salviati, accompanied by Vasari, moved to Rome. This was a critical juncture in his development. Rome, despite the recent trauma of the Sack of 1527, was still the epicenter of artistic innovation and patronage. Here, Salviati immersed himself in the study of classical sculpture and, crucially, the works of Raphael and Michelangelo, whose frescoes in the Vatican Stanze and the Sistine Chapel, respectively, were considered the pinnacle of artistic achievement.

It was in Rome that Francesco de' Rossi came under the patronage of Cardinal Giovanni Salviati, a prominent and wealthy churchman, and a nephew of Pope Leo X. This connection was so significant that Francesco adopted the surname of his patron, thereafter being known as Francesco Salviati (or Il Salviati). This was a common practice for artists seeking to align themselves with powerful benefactors. Under Cardinal Salviati's aegis, he received numerous important commissions. His early Roman works already demonstrated a sophisticated assimilation of Raphaelesque grace and Michelangelesque power, filtered through an emerging Mannerist sensibility. He collaborated with other artists, including Jacopino del Conte, on various projects.

One of his most significant early Roman commissions was the fresco decoration of the Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato, where he painted the Annunciation to Zacharias (1538) and the Visitation (c. 1538). These works, particularly the Visitation, are celebrated for their dynamic compositions, elongated figures in elegant, almost balletic poses, and a vibrant, sophisticated color palette. The figures, with their expressive gestures and intricate draperies, move within complex architectural settings, showcasing Salviati's growing mastery of perspective and his penchant for ornamental detail. These frescoes established his reputation as a leading young painter in Rome. He also worked on the Chapel of the Pallium in the Palazzo della Cancelleria.

Travels and Diverse Artistic Ventures

Salviati's career was characterized by a certain restlessness and a willingness to travel in pursuit of commissions, a trait common to many artists of the period. In 1539, he accompanied Cardinal Salviati to Bologna and then traveled to Venice. His Venetian sojourn, though relatively brief (1539-1541), was significant. He absorbed the influence of Venetian colorism and light, evident in the richer, more atmospheric qualities of some of his subsequent works. In Venice, he painted frescoes, now lost, for the Palazzo Grimani and an altarpiece, The Lamentation over the Dead Christ, for the Corpus Domini church. He would have encountered the works of masters like Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, whose emphasis on color and painterly texture offered a contrast to the more linear and sculptural traditions of Central Italian art.

After Venice, Salviati returned to Rome, where he continued to receive prestigious commissions. He worked in the Palazzo Sacchetti, decorating the Salone Grande with frescoes depicting the Story of David (c. 1553), showcasing his ability to handle large-scale narrative cycles with dramatic flair and complex figural arrangements. He also undertook commissions for the Farnese family, contributing to the decorations of the Palazzo Farnese, a major hub of artistic activity involving artists like Taddeo Zuccaro and Daniele da Volterra. His work in the Sala Paolina in Castel Sant'Angelo, depicting scenes from the life of Alexander the Great (or St. Paul, interpretations vary), further cemented his reputation.

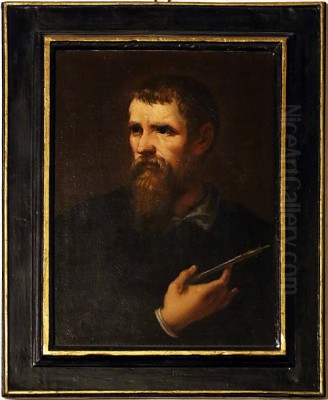

Salviati's versatility extended beyond fresco and panel painting. He was a highly accomplished portraitist, capturing the likenesses and status of his sitters with psychological acuity and a refined elegance. His portraits, such as the Portrait of a Young Man (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) or the Portrait of a Gentleman (Saint Louis Art Museum), are characterized by their polished surfaces, attention to costume and detail, and the often aloof, sophisticated demeanor of the subjects, typical of Mannerist portraiture as also practiced by artists like Bronzino. He also produced numerous designs for tapestries, a highly valued art form in the 16th century. His designs for the Medici manufactory in Florence, such as those for the Story of Joseph series, demonstrate his skill in creating complex, multi-figured compositions suitable for translation into woven form.

Return to Florence and Ducal Patronage

In 1543, Salviati returned to his native Florence, which was then under the rule of Duke Cosimo I de' Medici. Cosimo was an ambitious patron of the arts, keen to use art and architecture to project the power and prestige of his ducal state. Salviati quickly found favor with the Medici court and was commissioned to contribute to the extensive redecoration of the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of Florentine government. His most important work there is the fresco cycle in the Sala dell'Udienza (Audience Hall), depicting the Story of Marcus Furius Camillus (1543-1545). These frescoes are quintessential examples of high Mannerism, with their crowded compositions, muscular, contorted figures in elaborate poses (figura serpentinata), brilliant, almost metallic colors, and a wealth of classical and allegorical allusions. They celebrate the virtues of the Roman hero Camillus, implicitly drawing parallels with Duke Cosimo's own leadership.

During this Florentine period, Salviati worked alongside his old friend Giorgio Vasari, who was also heavily involved in the Palazzo Vecchio projects. While they were friends, a certain rivalry also existed between them, as was common among artists competing for prestigious commissions. Salviati's style, with its emphasis on intricate detail and polished finish, sometimes contrasted with Vasari's more rapid and robust manner. Other prominent Florentine contemporaries included Agnolo Bronzino, Cosimo I's court painter, whose coolly elegant portraits and allegories defined Medicean Mannerism, and sculptors like Benvenuto Cellini and Bartolomeo Ammannati. Salviati's Deposition from the Cross for the Santa Croce church (now in the Uffizi Gallery) is another major work from this period, showcasing his dramatic power and sophisticated use of color and light.

Artistic Style: The Essence of Mannerism

Francesco Salviati's art is a prime exemplar of Mannerism, an artistic style that flourished from roughly the 1520s to the end of the 16th century. Mannerism, meaning "style" or "manner," emerged as a reaction against, or an extension of, the High Renaissance. While High Renaissance art sought naturalism, harmony, and idealized beauty, Mannerism often embraced artificiality, elegance, and intellectual complexity.

Key characteristics of Salviati's Mannerist style include:

1. Elongated and Stylized Figures: His figures often possess elongated proportions, slender limbs, and small heads, moving with an affected grace and elegance. Poses are frequently complex and contorted, embodying the figura serpentinata (serpentine figure), which creates a sense of dynamism and sophistication.

2. Complex and Crowded Compositions: Salviati favored dense, multi-layered compositions, often filling the picture plane with numerous figures, architectural elements, and decorative details. Space can be ambiguous or compressed, challenging the clear perspectival systems of the High Renaissance.

3. Vibrant and Unnaturalistic Color: His palette is often characterized by bright, sometimes acidic or "shot" colors (cangiante), where hues change abruptly within a single form. These color choices contribute to the artificial and decorative quality of his work, moving away from the naturalistic color harmonies of artists like Raphael or Andrea del Sarto.

4. Emphasis on Virtuosity and Detail: Salviati's works display a high degree of technical skill and meticulous attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of fabrics, armor, and ornamental motifs. This virtuosity was highly prized by Mannerist patrons.

5. Intellectual Sophistication: Many of his works are rich in allegorical and mythological allusions, appealing to the erudite tastes of his courtly and ecclesiastical patrons. The meaning is often layered and not immediately apparent, inviting contemplation.

6. Emotional Intensity and Drama: While sometimes coolly elegant, Salviati could also imbue his religious and historical narratives with considerable emotional intensity and dramatic power, achieved through expressive gestures, dynamic movement, and dramatic lighting.

His style evolved throughout his career, absorbing influences from the various artistic centers he visited. His Roman works show a strong engagement with Raphael and Michelangelo; his Venetian period introduced a richer colorism; and his Florentine works for Cosimo I display the full-blown, courtly Mannerism favored by the Medici. He was a contemporary of other great Mannerists like Parmigianino, whose elegant stylizations share some affinities with Salviati's, and Giulio Romano, whose powerful and often licentious style in Mantua also pushed the boundaries of High Renaissance norms.

A Sojourn in France and Final Years

In 1556-1557, Salviati traveled to France, working for a time at the court of King Henry II, primarily at the Château de Dampierre for Cardinal Charles of Lorraine. The French court had already become a center for Italian Mannerist art, largely due to the earlier presence of Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio at Fontainebleau. Salviati's contribution in France, though not as extensive as that of the Fontainebleau school artists, further demonstrates the international reach of Mannerism.

He returned to Rome for the final phase of his career. Vasari recounts that Salviati's personality could be difficult and proud, leading to friction with patrons and fellow artists. This temperament, combined with his relentless drive, may have contributed to his somewhat peripatetic career. Despite any personal difficulties, his artistic output remained high. He continued to work on significant projects, including frescoes in the Sala Regia in the Vatican, a prestigious commission that also involved artists like Daniele da Volterra and Taddeo Zuccaro. His Incredulity of Saint Thomas (Louvre, Paris) is a notable late work.

Francesco Salviati died in Rome on November 11, 1563. He left behind a substantial body of work that significantly contributed to the development and dissemination of Mannerism throughout Italy and beyond.

Legacy and Influence

Francesco Salviati was one of the most inventive and technically proficient painters of his generation. His ability to synthesize influences from diverse sources—the Florentine tradition of disegno (drawing/design), Roman classicism and monumentality, Venetian color—and forge them into a distinctive and highly influential Mannerist style was remarkable. He excelled in large-scale fresco decoration, creating complex, dynamic narratives that adorned palaces and churches. His portraits captured the sophisticated and often aloof spirit of the Mannerist elite. His designs for tapestries and other decorative arts underscore the period's integration of all art forms.

His influence can be seen in the work of his pupils and followers. While he did not run a large, organized workshop in the manner of Raphael, artists who came into contact with him or studied his works absorbed elements of his style. His impact was felt not only in central Italy but also in Venice and, to some extent, in France. He, along with contemporaries like Bronzino, Vasari, Perino del Vaga, and Polidoro da Caravaggio, helped to define the visual language of Mannerism, a style that bridged the gap between the High Renaissance and the emergence of the Baroque. His art, with its elegance, complexity, and technical brilliance, remains a testament to the creative ferment of the 16th century and secures his place as a major master of Italian Mannerism. His works continue to be studied and admired in major museums and collections worldwide, offering a window into the sophisticated and often enigmatic world of 16th-century art.