William Strutt stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the annals of both British and Australian art history. Born in England and trained in the classical traditions of Paris, Strutt spent a crucial decade in Australia during a formative period of its colonial development. His meticulous eye and academic skill allowed him to capture pivotal moments, dramatic events, and the unique character of life in the mid-19th century Australian colonies. As an artist bridging the European academic world and the raw, burgeoning society of Australia, his work offers invaluable visual documentation and artistic insight into the era. This exploration delves into the life, artistic journey, influences, key works, and lasting legacy of William Strutt, placing him within the context of his contemporaries and the broader sweep of art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Europe

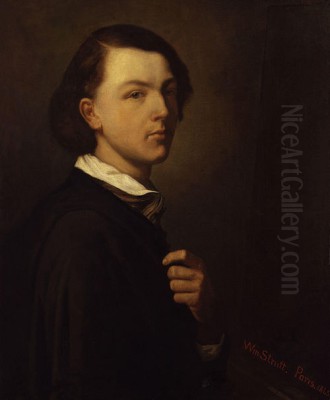

William Strutt was born on July 3, 1825, in Teignmouth, Devon, England, into a family already steeped in artistic and intellectual pursuits. His lineage provided a foundation conducive to an artistic career. His grandfather was Joseph Strutt (1749–1802), a noted author, artist, antiquary, and engraver, known for works like "Sports and Pastimes of the People of England." This connection to historical documentation and artistic representation likely influenced the younger Strutt's inclinations.

Furthermore, William's father, William Thomas Strutt (1777-1850), was a respected miniature painter. Growing up in such an environment, William was exposed to artistic practice from an early age. His formal training, however, took place primarily in Paris, a global centre for art education at the time. He moved there to study, immersing himself in the rigorous academic system.

Strutt studied under the tutelage of prominent figures like Michel Martin Drolling, a history painter working in the Neoclassical style. He also enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts around 1839. This institution emphasized drawing, anatomy, perspective, and the study of classical antiquity and Renaissance masters. The curriculum was designed to produce artists capable of tackling large-scale historical, religious, or mythological subjects with technical proficiency and compositional grandeur.

During his time in Paris, Strutt absorbed the prevailing artistic currents. He was particularly drawn to the works of the High Renaissance master Raphael, whose clarity of form, harmonious compositions, and idealized figures left a lasting impression. The influence of French Neoclassicism, exemplified by artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres with his emphasis on line and precise draughtsmanship, can also be discerned in Strutt's careful technique and structured compositions. His training instilled in him a commitment to accuracy, detail, and narrative clarity, principles that would define much of his later work.

The Australian Sojourn: A New World, A New Canvas

Despite his promising start in the European art world, health concerns prompted a significant change in Strutt's life trajectory. Seeking a climate more beneficial to his well-being, he emigrated to Australia, arriving in Melbourne in July 1850. This move coincided with a period of dramatic transformation in the colony of Victoria, primarily driven by the burgeoning gold rush that began the following year. Melbourne was rapidly evolving from a small settlement into a bustling, cosmopolitan city, attracting people from all corners of the globe.

Strutt arrived in a society grappling with rapid growth, social upheaval, and the challenges of establishing infrastructure and governance. This dynamic environment provided a wealth of subject matter for an artist trained to observe and record. He quickly found work, leveraging his skills as an illustrator for the newly established Illustrated Australian Magazine. This role required him to produce images depicting local events, landscapes, and social scenes, honing his ability to capture the specificities of Australian life.

His twelve years in Australia, from 1850 to 1862, proved to be the most defining period of his artistic career. He became an active participant in the nascent colonial art scene, documenting its key moments and figures. He witnessed firsthand the impact of the gold rush, the devastating effects of natural disasters, the complexities of colonial expansion, and the interactions between European settlers and Indigenous Australians. This direct experience infused his work with a sense of immediacy and authenticity, distinguishing it from depictions of Australia created purely from imagination or second-hand accounts back in Europe.

Chronicling Colonial Life and Landscape

Strutt's time in Australia was marked by a dedication to documenting the multifaceted life of the colony. His academic training provided him with the tools to tackle ambitious historical subjects, while his illustrator's eye captured the telling details of everyday existence. He painted portraits of prominent colonial figures, recorded significant public events, and depicted the unique flora, fauna, and landscapes of his adopted home.

His works often focused on dramatic incidents that highlighted the challenges and triumphs of colonial life. He was drawn to moments of crisis and heroism, reflecting a common theme in 19th-century history painting. Subjects included bushfires, encounters with bushrangers (outlaws who operated in the Australian bush), and the arduous journeys of exploration that sought to map the vast, unknown interior of the continent.

Strutt also turned his attention to the Indigenous peoples of Australia. While viewed through the lens of his time, his depictions often aimed for a degree of ethnographic accuracy, based on sketches made from life. Works like Aboriginal Obstructionists (though the title reflects colonial attitudes) attempt to portray specific cultural practices or encounters, providing valuable, if interpreted, visual records. He documented ceremonies, hunting practices, and daily life, contributing to the visual archive of Aboriginal culture during a period of profound disruption.

Beyond historical events and figure studies, Strutt also engaged with the Australian landscape, although perhaps less centrally than contemporaries like Eugene von Guérard. His landscapes often served as backdrops for narrative action, but they nonetheless captured the distinct light and features of the Australian environment, from the eucalyptus forests to the open plains. His meticulous approach extended to the depiction of native animals, which featured prominently in many of his major compositions.

Masterpiece: Black Thursday, February 6th, 1851

Among William Strutt's extensive body of work, one painting stands out as his most famous and arguably most powerful contribution to Australian art: Black Thursday, February 6th, 1851. Completed in 1864 after his return to England but based on extensive sketches and memories from his time in Victoria, this large-scale history painting depicts the catastrophic bushfires that swept across the colony on that fateful day.

The event itself was terrifying. Extreme heat and strong winds fuelled fires that consumed vast swathes of land, destroying homes, livestock, and vegetation, and claiming several lives. It was a shared trauma for the young colony, a stark reminder of the power and danger of the Australian environment. Strutt, having been in Melbourne at the time, likely heard numerous firsthand accounts and may have witnessed some of the aftermath.

His painting is a dramatic, almost apocalyptic, panorama of chaos and survival. It masterfully orchestrates a complex scene filled with fleeing settlers, terrified livestock (horses, cattle, sheep), native animals (kangaroos, emus, birds), and even insects, all desperately trying to escape the encroaching flames and suffocating smoke. The composition is dynamic, using diagonal lines and swirling forms to convey panic and movement. The sky glows an ominous red and orange, casting a lurid light on the figures below.

Black Thursday exemplifies Strutt's strengths: his academic skill in composing complex multi-figure scenes, his meticulous attention to detail (particularly in the rendering of animals), and his ability to convey high drama and emotion. It functions not only as a historical record of a specific event but also as a broader allegory of humanity and nature confronting overwhelming disaster. The painting is held in the collection of the State Library Victoria and remains one of the most iconic images of 19th-century Australian history.

Documenting the Burke and Wills Expedition

Another significant historical event that captured Strutt's attention was the Victorian Exploring Expedition, famously led by Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills. Launched from Melbourne in August 1860, the expedition aimed to be the first to cross the Australian continent from south to north. Strutt was present at the expedition's departure from Royal Park, Melbourne, a grand public spectacle reflecting the high hopes and national pride invested in the venture.

He meticulously sketched the scene, capturing the camels specially imported for the journey, the explorers, the officials, and the crowds of onlookers. These sketches formed the basis for later, more finished works. Although Strutt did not accompany the expedition itself, he followed its progress and tragic outcome with keen interest. The expedition ultimately succeeded in reaching the northern coast but ended in disaster on the return journey, with Burke, Wills, and several others perishing from starvation and exhaustion near Cooper Creek.

Strutt's connection to the expedition extended beyond the departure. He knew some of the participants, including Ludwig Becker, a fellow artist and naturalist who tragically died during the expedition. Years later, after returning to England, Strutt revisited his sketches and the expedition's dramatic story to create another major history painting, The Burial of Burke (completed 1862, though other versions and related works exist). This work depicts the somber discovery of Burke's remains by the relief party led by Alfred Howitt. It captures the pathos and heroism associated with the explorers, cementing their story in the visual narrative of Australian nation-building. His detailed drawings and paintings related to the expedition are invaluable historical documents.

Skill in Animal Painting

A recurring and notable feature of William Strutt's art is his exceptional skill in depicting animals. Whether as central subjects or as integral parts of larger narrative scenes, his animals are rendered with anatomical accuracy, vitality, and a sense of individual character. This proficiency likely stemmed from dedicated study and observation, possibly influenced by the tradition of animal painting that was strong in both British and French art of the period.

In Black Thursday, the terrified energy of the horses, the lumbering panic of the cattle, and the desperate flight of native fauna are crucial to the painting's impact. Strutt captures their movement and fear with convincing realism. His ability to integrate numerous animal figures into a complex composition without sacrificing detail is remarkable.

He also created works where animals were the primary focus. Love of the Dog (1861), for instance, showcases his sensitivity to animal emotion and form. Throughout his Australian works, native animals like kangaroos, emus, and various birds appear, rendered with careful attention to their specific characteristics. This interest extended to the imported animals that were becoming part of the colonial landscape, such as the camels of the Burke and Wills expedition and the horses essential for transport and agriculture. His dedication to animal portrayal adds a distinct dimension to his oeuvre, setting him apart from many contemporaries.

Other Notable Works and Themes

Beyond his most famous history paintings, Strutt's output was diverse. He produced numerous portraits, capturing the likenesses of colonial administrators, settlers, and fellow artists. These portraits often display the careful finish and psychological insight characteristic of academic portraiture.

His work Bushrangers on the St Kilda Road (related sketches exist, final painting possibly later or titled differently, sometimes referred to as The Bushranger, 1860) tackled another potent theme in Australian colonial history. Bushranging was a significant social phenomenon, and artists like Strutt sought to capture the drama and fear associated with these figures who operated outside the law. Such works often played into popular narratives of danger and adventure in the colonies.

Religious themes also appeared in his work, reflecting both his personal faith and the conventions of academic art, which held religious painting in high regard. After returning to England, he continued to produce works with historical and sometimes allegorical themes, such as Peace (1896), considered an important later work. He also engaged in symbolic or humorous subjects, showcasing a lighter side to his artistic personality. Throughout his career, his sketchbook remained an essential tool, filled with observations, preparatory drawings, and records of his experiences, many of which formed the basis for larger oil paintings completed years later.

Artistic Style and Development

William Strutt's artistic style was fundamentally rooted in the European academic tradition he absorbed in Paris. Key characteristics include strong draughtsmanship, balanced compositions, a high degree of finish, meticulous attention to detail, and a focus on narrative clarity. His work often displays the influence of Neoclassicism, particularly in the structured arrangement of figures and the emphasis on anatomical accuracy, echoing masters like Ingres. There is also a dramatic, sometimes Romantic, sensibility in his choice of subjects and his rendering of intense emotion, particularly in scenes of disaster or conflict, perhaps drawing inspiration from artists like Eugène Delacroix.

His time in Australia introduced new subject matter and a unique environment, which inevitably impacted his work. While maintaining his academic technique, he adapted it to depict the specific light, landscapes, and social conditions of the colonies. His realism was applied to capturing the details of colonial dress, architecture, and the natural world.

The provided text mentions a later shift towards Impressionism, although it qualifies this by suggesting the transition was not entirely successful. It's important to contextualize this. By the time Strutt returned to England in 1862 and continued painting into the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Impressionism had revolutionized the art world. Compared to the looser brushwork, emphasis on light and colour, and focus on fleeting moments characteristic of Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro in France, or later Australian Impressionists like Arthur Streeton and Tom Roberts, Strutt's work remained largely anchored in his earlier academic training. While his later works might show some subtle shifts, he never fully embraced the Impressionist aesthetic. His commitment remained primarily with detailed historical and narrative painting, a style that was becoming less fashionable by the turn of the century.

Contemporaries and Context

Placing William Strutt within his artistic context requires looking at several circles of influence and interaction. His teachers, Michel Martin Drolling, and the broader influence of the École des Beaux-Arts and masters like Raphael and Ingres, shaped his foundational style. His family, grandfather Joseph Strutt and father William Thomas Strutt, provided an artistic background.

In Australia, he was part of a developing art scene in Melbourne. While direct, detailed records of his interactions with every contemporary are scarce, he would have been aware of, and likely known, other artists active during his time there (1850-1862). Figures like Ludwig Becker, the German artist-naturalist who perished with Burke and Wills, were part of this milieu. Eugene von Guérard, known for his detailed Romantic landscapes, and Nicholas Chevalier, another artist who documented colonial life and landscapes, were also prominent contemporaries in Victoria. S.T. Gill, though working more often in watercolour and known for his lively, sometimes satirical, depictions of goldfields life, was another key visual chronicler of the era. While the provided text notes John Pascoe Fawkner's influence on the early Melbourne scene, it confirms no specific interaction between him and Strutt.

Upon his return to England, Strutt continued to work, but the art world was changing. The rise of Impressionism and later movements shifted critical and popular taste away from the large-scale historical and narrative paintings in which he specialized. In Australia itself, the 1880s saw the emergence of the Heidelberg School, with artists like Arthur Streeton, Frederick McCubbin, Tom Roberts, and Charles Conder forging a distinctively Australian version of Impressionism, focused on capturing the unique light and atmosphere of the local landscape. Their style and nationalistic focus came to dominate Australian art history narratives, sometimes overshadowing the contributions of earlier colonial artists like Strutt. European academic contemporaries whose work might bear comparison in terms of subject or finish could include Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his detailed historical and Orientalist scenes.

Legacy and Reception

William Strutt's legacy is complex. During his lifetime, particularly after his return to England, he did not achieve the widespread fame or recognition that might have been expected given his skill and the significance of his subjects. The decline in popularity of academic history painting in the face of newer movements like Impressionism contributed to this relative obscurity. In Australia, while his works were acquired by institutions, his name became less prominent compared to the later generation of Australian Impressionists who captured the national imagination.

However, from a historical perspective, Strutt's contribution is immense. His paintings and sketches provide invaluable visual records of a crucial period in Australian history. Works like Black Thursday and his documentation of the Burke and Wills expedition are more than just artworks; they are historical documents that offer insights into the events, environment, and social fabric of the mid-19th century colonies. His meticulous attention to detail, even when filtered through artistic convention, preserves information about clothing, equipment, architecture, and even the natural environment of the time.

Today, his work is highly regarded by art historians and curators, particularly those specializing in colonial Australian art. Major galleries and libraries in Australia, including the National Gallery of Victoria, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Art Gallery of South Australia, the State Library Victoria (which holds Black Thursday and many sketches), and the National Library of Australia, hold significant collections of his work. His paintings are frequently included in exhibitions exploring Australian history and art.

While he may not have become a household name in the same way as some of his contemporaries or successors, William Strutt is recognized as a highly skilled artist whose unique position – an academically trained European observing and participating in the life of colonial Australia – allowed him to create a body of work of enduring artistic and historical significance. He remains a key figure for understanding the visual culture of 19th-century Australia.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Worlds

William Strutt's life and art traversed continents and artistic eras. Trained in the rigorous academic traditions of Paris, he brought a European sensibility and technical mastery to the raw, dynamic environment of colonial Australia. For twelve crucial years, he dedicated his skills to documenting the landscape, people, and pivotal events of his adopted home, creating works that remain powerful testaments to that period. His masterpieces, particularly Black Thursday and his depictions related to the Burke and Wills expedition, secure his place as a major historical painter of Australia.

While changing artistic tastes may have led to a period where his contributions were somewhat overshadowed, contemporary appreciation recognizes the immense value of his work. His meticulous realism, his skill in complex compositions, his sensitive portrayal of animals, and his dedication to narrative clarity make his paintings compelling viewing. More importantly, they serve as vital visual records, offering a window into the challenges, tragedies, and aspirations of mid-19th-century Australia. William Strutt remains a significant chronicler, an artist whose brush captured the essence of a world undergoing profound transformation.