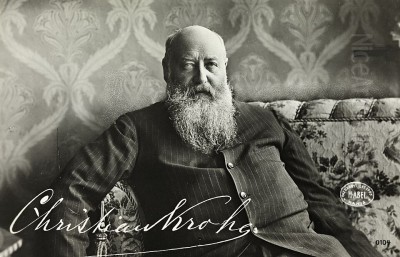

Christian Krohg stands as a towering figure in Norwegian art history, a multifaceted talent whose influence extended far beyond the canvas. Born in Vestre Aker, near Oslo, on August 13, 1852, and passing away in Oslo on October 16, 1925, Krohg was not only a pivotal painter associated with Realism and Naturalism but also a respected illustrator, a provocative novelist, and an insightful journalist. His life and work were deeply intertwined with the social and cultural transformations of late 19th and early 20th century Norway, making him a crucial voice for the underrepresented and a keen observer of the human condition. His legacy is defined by his unflinching portrayal of everyday life, particularly the struggles of the urban poor, and his significant role in shaping the direction of Norwegian art through both his creations and his teaching.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Christian Krohg hailed from a respectable background; he was one of five children born to Georg Anton Krohg, a civil servant and politician, and Sophie Amalia Holst. Following the path expected of many young men of his standing, Krohg initially pursued a career in law, enrolling at the University of Oslo (then known as the Royal Frederick University). He dutifully completed his legal studies, earning his degree. However, the pull towards art proved irresistible. Even during his law studies, his passion for drawing and painting flourished, hinting at the different direction his life would ultimately take.

The formal decision to dedicate himself to art led him abroad, a common trajectory for aspiring Scandinavian artists seeking advanced training. He first traveled to Germany, enrolling at the Baden School of Art in Karlsruhe. There, he studied under the guidance of prominent figures like Hans Gude, a fellow Norwegian renowned for his majestic landscape paintings, who became an important early mentor. Krohg absorbed the tenets of the Düsseldorf school's detailed realism, though his own path would soon diverge towards a more socially engaged form of expression.

His artistic education continued in Berlin from 1875. In the vibrant German capital, he studied under Karl Gussow, a painter known for his technical skill and realistic portraiture. This period was crucial for honing his technical abilities, particularly in figure painting and composition. Berlin also exposed him to a dynamic intellectual environment. He formed connections with influential figures such as the German artist Max Klinger, known for his Symbolist etchings and sculptures, and, significantly, the Danish literary critic Georg Brandes. Brandes, a leading proponent of the "Modern Breakthrough" in Scandinavian literature and thought, advocated for literature and art that engaged with contemporary social issues, an idea that resonated deeply with Krohg and profoundly shaped his artistic philosophy.

The Parisian Influence and the Embrace of Realism

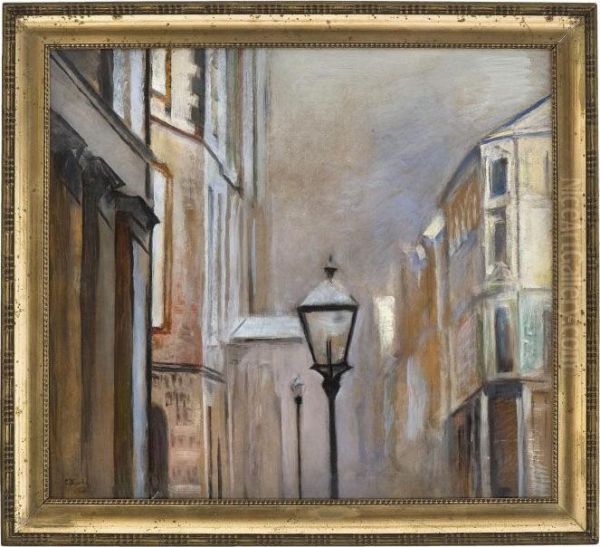

Like many artists of his generation, Krohg was drawn to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the latter half of the 19th century. His time spent in the French capital, particularly during the early 1880s, marked a significant turning point in his stylistic development. He encountered the revolutionary movements of French Realism and Impressionism firsthand, absorbing their lessons and adapting them to his own artistic temperament and thematic concerns.

The impact of French Realism, pioneered by artists like Gustave Courbet, reinforced Krohg's inclination towards depicting unvarnished reality and the lives of ordinary people. However, it was the influence of Impressionism, particularly the work of Édouard Manet, that arguably had the most visible effect on his technique. Manet's bold brushwork, his interest in contemporary urban life, and his often controversial subject matter provided a powerful model. Krohg began to adopt a looser, more visible brushstroke, a brighter palette, and a greater sensitivity to the effects of light and atmosphere, moving away from the tighter, more academic finish of his German training.

While embracing aspects of Impressionist technique, Krohg never fully adopted its focus on fleeting moments and sensory perception above all else. His commitment remained rooted in the narrative and social potential of art. He skillfully blended the Impressionists' innovations in light and color with the solid draftsmanship and compositional structure learned earlier, creating a powerful and distinctive style of Realism. This synthesis allowed him to depict his subjects with both immediacy and profound psychological depth. His connection to the Skagen Painters colony in Denmark during summers also exposed him to similar concerns with light and everyday life, shared with artists like Michael Ancher, Anna Ancher, and Peder Severin Krøyer.

Naturalism and Unflinching Social Commentary

Christian Krohg became a leading exponent of Naturalism in Norwegian art. This movement, closely related to Realism but often emphasizing a more deterministic view of human life shaped by environment and heredity, found fertile ground in Krohg's artistic vision. He turned his gaze towards the segments of society often ignored or romanticized by earlier art forms: the urban working class, sailors, fishermen, and, most controversially, prostitutes and the destitute. His work was driven by a powerful social conscience and a desire to expose the harsh realities faced by the marginalized.

Krohg's paintings from this period are characterized by their directness and lack of sentimentality. He did not shy away from depicting poverty, illness, exhaustion, and exploitation. His subjects are portrayed with empathy but also with an objective clarity that forces the viewer to confront uncomfortable truths about modern society. He saw art as a tool for social critique, a means to shed light on injustice and provoke discussion. His commitment went beyond mere observation; it was an active engagement with the pressing social issues of his time, reflecting the broader intellectual currents championed by figures like Georg Brandes.

His focus on specific professions and social strata was notable. He painted numerous scenes depicting the hard lives of Norwegian sailors and pilots, capturing their resilience and the dangers they faced at sea. These works often displayed a dynamic energy and a keen understanding of maritime life. Similarly, his depictions of the urban poor, often set in cramped interiors or stark institutional settings, conveyed a palpable sense of struggle and vulnerability. Through these works, Krohg contributed significantly to a more democratic and socially aware form of art in Norway.

Major Works: Controversy and Acclaim

Several of Christian Krohg's works stand out not only for their artistic merit but also for the public debate they ignited. His most famous and controversial project centered around the figure of "Albertine," a young seamstress forced into prostitution by poverty. This theme culminated in his 1886 novel, Albertine. The book's explicit depiction of the circumstances leading to Albertine's fate, and its critique of the societal hypocrisy and public regulation of prostitution, caused a scandal. Upon publication, the novel was immediately confiscated by the police and banned, and Krohg faced legal action, although the charges were eventually dropped. The controversy, however, cemented Krohg's reputation as a fearless social critic.

Complementing the novel was his equally powerful painting, Albertine i politilægernes venteværelse (Albertine in the Police Doctor's Waiting Room), completed around the same time. This large canvas depicts a group of prostitutes, including Albertine, waiting for a mandatory medical examination, a humiliating procedure required by law. The painting's stark realism, the weary and resigned expressions of the women, and the drab, institutional setting combined to create a devastating indictment of the system and the social conditions that produced it. The work provoked outrage among conservative elements of society but was hailed by progressives as a masterpiece of social realism.

Another significant work exploring themes of suffering and mortality is Syk pike (Sick Girl), painted in 1880-81. Often compared to Edvard Munch's later painting of the same name (Munch was Krohg's student and friend), Krohg's version depicts a young girl near death, capturing the somber atmosphere of the sickroom with poignant realism. The painting shocked contemporary audiences with its direct confrontation with illness and death, subjects often treated with more sentimentality in academic art. Its unflinching portrayal demonstrated Krohg's commitment to depicting life's harsh realities.

Beyond these socially charged works, Krohg was also a masterful portraitist and painter of genre scenes. His portrait of the Danish poet and painter Holger Drachmann captures the sitter's bohemian energy with vibrant brushwork influenced by Impressionism. Works like Badet (The Bath), showing a mother bathing her child, demonstrate his ability to handle intimate domestic scenes with warmth and a keen sense of light and atmosphere, again showing Impressionist influence in the handling of indoor light. His maritime paintings, such as Hardt le (Hard Aboard), vividly convey the drama and skill involved in seafaring life, a recurring theme reflecting Norway's deep connection to the sea. He also painted monumental historical works, such as Leiv Eiriksson oppdager Amerika (Leif Erikson Discovers America), commissioned for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The Kristiania Bohemians and Radical Circles

Christian Krohg was a central figure in the "Kristiania Bohemians" (Kristiania-bohemen), a radical group of writers and artists active in the Norwegian capital (then called Kristiania) during the 1880s. This circle, heavily influenced by anarchist ideas and a rejection of bourgeois morality, advocated for social change and personal freedom, including free love and the challenging of traditional sexual norms. The group's intellectual leader was the writer Hans Jæger, whose own controversial novel Fra Kristiania-Bohêmen (From the Kristiania Bohemians) also faced confiscation and led to his imprisonment.

Krohg's association with this group underscores his commitment to challenging societal conventions, both through his art and his personal associations. He shared their desire to break down taboos and discuss openly issues of morality, sexuality, and social injustice. In 1886, alongside Jæger and others, Krohg briefly co-edited the journal Impressionisten (The Impressionist), which served as a platform for their radical ideas. Though short-lived, the journal exemplified the group's provocative stance and their engagement with contemporary debates.

The Bohemian circle included other notable figures, and its influence extended to younger artists like Edvard Munch, who absorbed their emphasis on subjective experience and psychological exploration, even as he moved towards Symbolism and Expressionism. Krohg's role within this milieu was significant; he provided a visual counterpart to the literary radicalism of Jæger, using his art to explore the themes that animated their discussions. His involvement demonstrates his position at the forefront of Norway's cultural avant-garde during a period of intense social and intellectual ferment.

Krohg as Writer and Journalist

Christian Krohg's creative output was not confined to the visual arts. He was also a gifted writer and an active journalist, using the written word to complement and expand upon the themes explored in his paintings. His most famous literary work remains the novel Albertine (1886), whose banning paradoxically ensured its lasting fame and impact. The novel provided a detailed narrative context for the plight depicted in his paintings, offering a powerful critique of the social mechanisms that led to exploitation.

Beyond Albertine, Krohg authored several other books and numerous articles. He published collections of interviews and reportages, often focusing on the lives of ordinary people he encountered. His journalistic work, particularly during his time writing for the influential newspaper Verdens Gang between 1890 and 1910, allowed him to reach a broad audience with his observations on art, society, and politics. His writing style was often direct, engaging, and infused with the same empathy and critical perspective found in his visual art.

His articles frequently discussed art criticism and theory, advocating for the principles of Realism and Naturalism and defending artists who challenged academic conventions. He wrote insightful pieces about fellow artists, both Norwegian and international, contributing to the public understanding and appreciation of contemporary art. This dual practice as both artist and writer gave Krohg a unique platform, enabling him to articulate his artistic and social vision through multiple mediums and reinforcing his role as a public intellectual. His writings provide invaluable insights into his own work and the cultural climate of his time.

Teaching and Academic Leadership: Shaping the Next Generation

Christian Krohg's influence on Norwegian art was significantly amplified through his long career as an educator. He began teaching at various private art schools before becoming a central figure at the Norwegian National Academy of Fine Arts (Statens Kunstakademi) in Oslo. He was appointed professor and served as the Academy's first director from its establishment in 1909 until his death in 1925. This position placed him at the heart of artistic training in Norway for over a decade and a half.

As a teacher, Krohg was known for his emphasis on solid draftsmanship, direct observation, and the importance of engaging with contemporary life. He encouraged his students to develop their individual styles while grounding their work in a strong technical foundation. His own artistic practice, rooted in Realism but open to modern influences, provided a compelling model. He fostered an environment that was receptive to new ideas, even as he maintained a focus on representational art.

His most famous student was undoubtedly Edvard Munch. Krohg recognized Munch's burgeoning talent early on, offering crucial encouragement and guidance during Munch's formative years in the 1880s. While Munch would ultimately forge a radically different path towards Expressionism, Krohg's early support and his own example of artistic integrity and social engagement were important influences. Beyond Munch, Krohg taught and mentored generations of Norwegian artists, shaping the landscape of Norwegian art in the early 20th century. His leadership at the Academy helped establish it as a vital institution for artistic development in the country. Other notable Norwegian artists active during his time, representing various styles but part of the same artistic milieu, included his brother-in-law Frits Thaulow, Erik Werenskiold, Harriet Backer, Eilif Peterssen, and Gerhard Munthe.

Later Career, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Christian Krohg remained an active and respected figure in the Norwegian art world until his death in 1925. While his most radically Naturalist works belong to the 1880s and 1890s, he continued to paint, write, and teach with vigor. His later work sometimes showed subtle shifts, perhaps incorporating a slightly broader handling or exploring different themes, but his fundamental commitment to realism and human subjects remained constant. He continued to produce insightful portraits and scenes from everyday life.

His legacy is immense and multifaceted. As a painter, he is celebrated as one of the foremost figures of Norwegian Realism and Naturalism, an artist who dared to tackle difficult social issues with honesty and artistic power. His works, particularly Albertine (both the painting and the novel), remain iconic examples of socially engaged art in Scandinavia. They continue to provoke discussion about art's role in society and the historical realities of poverty and exploitation.

As a writer and journalist, he contributed significantly to the cultural debates of his era. As a teacher and the first director of the National Academy of Fine Arts, he played a crucial role in institutionalizing art education in Norway and nurturing future generations of artists. His influence extended to Edvard Munch and many others who passed through the Academy or were part of the Kristiania art scene. He interacted, sometimes contentiously, with figures like the Swedish artist and writer August Strindberg, reflecting the vibrant, often competitive, artistic exchanges of the time.

Internationally, while perhaps less known than Munch, Krohg's work was exhibited abroad, including at the Chicago World's Fair, and recognized as part of the broader movement of European Realism. He stands as a key transitional figure, bridging 19th-century academic traditions and the emerging modernism of the 20th century. His unwavering focus on the human condition, rendered with technical skill and profound empathy, ensures his enduring importance in the history of Norwegian and Scandinavian art.

Conclusion: A Voice for the Voiceless

Christian Krohg was more than just a painter; he was a vital cultural force in Norway during a period of profound societal change. His dedication to depicting the realities of life, particularly for the marginalized and overlooked, set him apart. Through his powerful paintings like Albertine i politilægernes venteværelse and Syk pike, his controversial yet impactful novel Albertine, his insightful journalism, and his dedicated teaching, he consistently used his talents to foster social awareness and challenge complacency. He masterfully blended the techniques learned from German academism and French Impressionism to forge a unique and potent style of Realism. As a central figure among the Kristiania Bohemians and the first director of the National Academy of Fine Arts, his influence permeated Norwegian artistic and intellectual life. Christian Krohg remains a pivotal figure, remembered for his artistic skill, his courage in tackling difficult subjects, and his enduring commitment to social justice through art.