The Dutch Golden Age, spanning roughly the 17th century, was a period of extraordinary artistic efflorescence in the newly independent Dutch Republic. Fueled by burgeoning trade, scientific discovery, and a prosperous merchant class eager to adorn their homes, a unique art market developed, catering to diverse tastes. Within this vibrant milieu, artists specialized in genres that reflected the values and interests of their society: portraits, scenes of daily life, seascapes, landscapes, and the exquisitely detailed still lifes. Among the many talented painters of this era, Christoffel van den Berge, though perhaps not as universally renowned as Rembrandt van Rijn or Johannes Vermeer, carved out a significant niche for himself, particularly in the realms of landscape and flower still life painting. His work, characterized by meticulous detail and a quiet elegance, offers a fascinating window into the artistic currents of his time, particularly in the influential artistic center of Middelburg.

A Life Rooted in Middelburg

Christoffel van den Berge was born around 1588, likely in the Southern Netherlands (Flanders), a region with a rich artistic heritage. Like many Flemish families seeking refuge from religious persecution or economic hardship following the Spanish reconquest of the Southern Netherlands, his family is believed to have migrated north to the Dutch Republic. They settled in Middelburg, the capital of the province of Zeeland. Middelburg, a thriving port city with strong international trade links, became an important cultural and artistic hub in the early 17th century, attracting numerous artists, including prominent figures like the flower painter Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder.

Van den Berge’s professional life appears to have been centered entirely in Middelburg. Archival records indicate his activity as a painter primarily between 1617 and his death, which is generally accepted to have occurred around 1628, though some older sources occasionally cite a later date. A pivotal moment in his career was his enrollment in the Middelburg Guild of Saint Luke in 1619. The Guild of Saint Luke, present in many European cities, was the primary organization for painters, sculptors, engravers, and other craftsmen. Membership was essential for an artist to practice their trade legally, take on apprentices, and sell their work.

His standing within the artistic community of Middelburg is further evidenced by his election as dean (or head) of the Guild in 1621. This position would have involved administrative responsibilities and represented a mark of respect from his peers. It suggests that, despite a relatively short documented career, van den Berge was a recognized and esteemed figure in the local art scene. Further testament to his stability and success in Middelburg is the record of him purchasing a house in the city, where he presumably lived and worked until his passing. Despite these biographical anchor points, much about his personal life, his specific training, and the full extent of his social and professional connections remains elusive, a common challenge when researching artists from this period whose fame did not reach the stratospheric levels of a select few.

The Artistic Milieu of Middelburg and Key Influences

Middelburg in the early 17th century was a crucible of artistic innovation, particularly for still life painting. The city's role as a trading center meant access to exotic goods, including rare flowers and shells, which became popular subjects for painters. The presence of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (c. 1573–1621) was particularly formative for the development of flower painting in Middelburg. Bosschaert, himself a Flemish émigré, was a pioneer of the genre, known for his symmetrically arranged, brightly lit, and minutely detailed bouquets, often featuring flowers that bloomed in different seasons, gathered into a single, idealized composition.

It is widely believed that Christoffel van den Berge was either a direct pupil of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder or, at the very least, profoundly influenced by his style. The similarities in their approach to flower painting – the meticulous rendering of individual petals and leaves, the inclusion of insects and dewdrops, the often formal and somewhat stiff arrangement of blooms – are striking. Bosschaert’s workshop was a family affair, including his three sons, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Younger, Johannes Bosschaert, and Abraham Bosschaert, as well as his brother-in-law, Balthasar van der Ast, all of whom became accomplished still life painters. Van den Berge’s work fits comfortably within this "Bosschaert school" or Middelburg school of flower painting.

Beyond the immediate circle of Bosschaert, van den Berge’s art also shows an awareness of broader Flemish artistic traditions. His landscape paintings, for instance, echo the detailed, often wooded scenes popularized by earlier Flemish masters like Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his son Jan Brueghel the Elder, known as "Velvet" Brueghel for his smooth brushwork. Jan Brueghel the Elder was himself a master of both landscapes and flower still lifes, often collaborating with figures like Peter Paul Rubens. The influence of other Flemish émigré landscape painters active in the Dutch Republic, such as Gillis van Coninxloo and Roelandt Savery (who also worked in Utrecht and was known for his detailed depictions of flora and fauna), can also be discerned. Savery, in particular, shared an interest in meticulous detail and exotic subjects, which resonated with the scientific curiosity of the age.

The artistic environment was one of cross-pollination. While specialization was common, artists were aware of developments in other genres and by other painters. The precision evident in van den Berge's still lifes, for example, is a quality shared with many Dutch landscape painters of the period, such as Esaias van de Velde or Hendrick Avercamp, who meticulously documented the Dutch countryside and its activities.

Van den Berge's Oeuvre: A Closer Look

Christoffel van den Berge’s surviving body of work is not extensive, but the quality of the known pieces attests to his skill and dedication. His paintings are primarily executed on a relatively small scale, often on copper or panel, which allowed for a high degree of finish and detail. His oeuvre can be broadly divided into two main categories: still lifes, predominantly flower pieces, and landscapes.

Landscapes: Capturing the Dutch Environment and Narrative Scenes

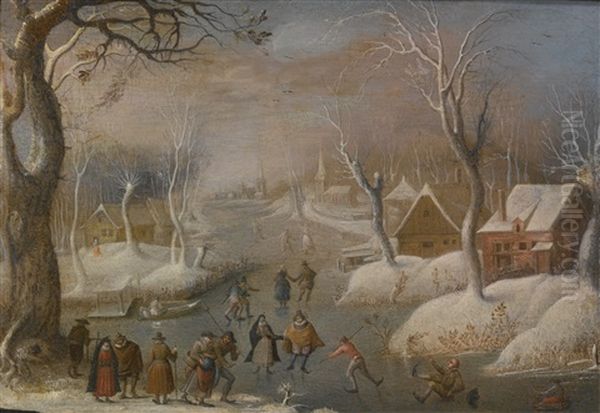

Van den Berge’s landscapes often depict serene, wooded environments, sometimes populated with small figures of travellers, hunters, or, in one notable instance, ice skaters. These scenes are rendered with a careful attention to the textures of foliage, the play of light through trees, and the atmospheric perspective that lends depth to the composition.

One of his well-regarded works is Winter Landscape, which captures a quintessential Dutch scene: figures enjoying themselves on a frozen waterway. Such winter scenes were a popular subgenre in Dutch landscape painting, pioneered by artists like Hendrick Avercamp. Van den Berge’s interpretation showcases his ability to convey the crisp atmosphere of winter and the lively human activity within a meticulously structured natural setting. The details, from the rendering of the bare branches of trees to the individual postures of the skaters, are precisely observed.

Another example, sometimes titled A Wooded Landscape with Travellers Being Ambushed on a Path at the Edge of a Wood, demonstrates a more narrative inclination, influenced by the Flemish tradition of incorporating small anecdotal scenes within a larger landscape. The dense foliage and the careful delineation of the path leading into the woods are characteristic of his style. These landscapes, while perhaps not as innovative as those of later Dutch masters like Jacob van Ruisdael or Meindert Hobbema, possess a charm and a dedication to detailed representation that aligns with the prevailing tastes of the early 17th century. They often retain a slightly higher viewpoint, a characteristic inherited from earlier Flemish landscape traditions, before the typically Dutch low-horizon views became dominant.

Still Lifes: The Ephemeral Beauty of Flora

It is perhaps in his still life paintings, particularly his flower pieces, that Christoffel van den Berge’s connection to the Middelburg school and the influence of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder are most apparent. These works are celebrations of nature's beauty, rendered with an almost scientific precision.

A prime example is his Still Life with Flowers in a Vase, dated 1617, now housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This painting, executed on copper, features a vibrant bouquet of flowers, including irises, tulips, roses, daffodils, columbines, and forget-me-nots, arranged in an ornate vase, possibly a Wanli porcelain piece imported from China, which were highly prized luxury items. Each flower is depicted at its peak of perfection, with individual petals and leaves rendered with painstaking care. The composition is typically symmetrical and somewhat formal, characteristic of early flower painting.

Van den Berge, like Bosschaert and Balthasar van der Ast, often included small insects – butterflies, caterpillars, beetles, or flies – and dewdrops on the petals and leaves. These elements served multiple purposes: they demonstrated the artist's virtuosity in capturing minute details (a quality known as fijnschilderij), added a sense of naturalism and life to the arrangement, and could also carry symbolic meaning. Flowers themselves were imbued with symbolism: roses might signify love or the Virgin Mary, tulips (especially rare varieties) could represent wealth and speculation (presaging the "Tulip Mania" of the 1630s), while irises were often associated with royalty or wisdom. The insects, too, could have symbolic connotations, often alluding to the transience of life and earthly beauty (vanitas), as flowers inevitably wilt and insects have short lifespans. Shells, another common element in Middelburg still lifes, reflecting the city's maritime trade, also appear in some of his compositions, further showcasing his skill in rendering diverse textures.

His flower paintings are characterized by bright, clear lighting that illuminates each bloom distinctly. There is less emphasis on dramatic chiaroscuro (the play of light and shadow) than would be seen in later Baroque still lifes by artists like Jan Davidsz. de Heem or Willem Kalf. Instead, the focus is on the individual beauty and precise rendering of each element within the carefully constructed bouquet.

Artistic Style and Technique

Christoffel van den Berge’s artistic style is defined by its precision, clarity, and meticulous attention to detail. Whether depicting the delicate veins on a petal, the intricate patterns on an insect's wing, or the varied textures of a landscape, his brushwork is controlled and refined. This dedication to verisimilitude was highly valued in the Dutch art market, where patrons appreciated the skill involved in creating such lifelike representations.

His use of color is typically bright and clear, especially in his flower still lifes, where the vibrant hues of the blooms are set against a darker, neutral background, making them stand out vividly. In landscapes, his palette is more subdued, reflecting the natural tones of the Dutch environment, but still with a careful modulation of light and shadow to create a sense of depth and form.

The choice of support, often copper for his still lifes, contributed to the smooth, enamel-like finish of his paintings. Copper provides a rigid, non-absorbent surface that allows for very fine brushwork and enhances the luminosity of the oil paints. This preference for small-scale, highly finished works on copper or smooth wooden panels was common among artists specializing in detailed cabinet pictures, including many of the Bosschaert circle and other fijnschilders like Gerrit Dou (a pupil of Rembrandt).

While his compositions, particularly in still lifes, can appear somewhat formal or even stiff by later Baroque standards, they possess an undeniable elegance and a sense of ordered beauty. This formality was characteristic of the earlier phase of Dutch still life painting, before artists like Jan Davidsz. de Heem introduced more dynamic, asymmetrical arrangements and a richer, more atmospheric use of light. Van den Berge’s work represents a crucial stage in the development of these genres, bridging the gap between earlier traditions and the later flourishing of Dutch Golden Age painting.

Rediscovery and Legacy

For many years after his death, Christoffel van den Berge, like many competent but not superstar artists of his era, faded somewhat into obscurity. His limited oeuvre and the scarcity of detailed biographical information contributed to this. However, the resurgence of art historical interest in the Dutch Golden Age during the 20th century led to a re-evaluation of many lesser-known masters.

It was particularly in the 1950s that scholarly attention began to focus more intently on van den Berge. Art historians, through careful stylistic analysis and the study of signatures and archival records, began to distinguish his hand more clearly and, in some cases, reattribute works that had previously been assigned to other artists, including Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder or Balthasar van der Ast. This process of rediscovery has helped to solidify his identity as a distinct artistic personality within the Middelburg school.

Today, Christoffel van den Berge is recognized as a skilled and significant painter of the early Dutch Golden Age. His works are held in prestigious museum collections, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Mauritshuis in The Hague (though attributions can sometimes shift). While his output may have been modest compared to some of his contemporaries, his paintings offer valuable insights into the artistic practices and aesthetic preferences of his time. He exemplifies the high level of craftsmanship and the specialized focus that characterized much of Dutch 17th-century art.

His contribution lies in his mastery of detail, his elegant depiction of the natural world, and his role within the influential Middelburg circle of painters. He helped to establish and popularize the genres of flower still life and detailed landscape painting, which would continue to evolve and flourish throughout the Dutch Golden Age in the hands of artists like Rachel Ruysch, Jan van Huysum in flower painting, and Aelbert Cuyp in landscape.

Conclusion

Christoffel van den Berge stands as a testament to the depth and breadth of talent active during the Dutch Golden Age. Though his name may not be as instantly recognizable as some, his surviving works reveal an artist of considerable skill, sensitivity, and dedication to his craft. His meticulously rendered flower still lifes and carefully observed landscapes capture the Dutch fascination with the natural world and the burgeoning pride in their own environment. As a key figure in the Middelburg school, likely closely associated with Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, van den Berge played a role in shaping the early development of genres that would become hallmarks of Dutch art. His paintings, with their quiet beauty and exquisite detail, continue to engage and delight viewers, offering a precious glimpse into the rich artistic tapestry of 17th-century Holland and securing his place as a noteworthy master of his time.