De Scott Evans was a notable American painter of the late 19th century, whose life and career offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic currents and social fabric of his time. Born David Scott Evans, he later adopted "De Scott Evans" as his professional name, under which he achieved recognition for his versatile talents in portraiture, genre scenes, and particularly, still life paintings rendered with astonishing trompe l'oeil realism. His work, though sometimes created under various pseudonyms, reflects a meticulous technique honed through academic training both in the American Midwest and in Paris, under the tutelage of celebrated masters. Evans's art often captured the refined sensibilities of Victorian America, yet he also possessed a keen eye for the everyday, imbuing humble objects with a sense of wonder and, at times, subtle social commentary. His tragic death at sea cut short a promising career, but his surviving works continue to intrigue and delight viewers, securing his place in the annals of American art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

David Scott Evans was born on March 28, 1847, in Boston, Wayne County, Indiana, a small community that would hardly seem the crucible for an aspiring artist. However, artistic talent often emerges in unexpected places. His parents were David S. Evans and Nancy J. Evans. From a young age, Evans displayed a natural inclination towards art. Anecdotal evidence suggests his early creative impulses found expression in unconventional ways; one story recounts him, as a boy, impressively drawing a portrait of George Washington on a headboard, hinting at a precocious ability for capturing likenesses and a burgeoning artistic ambition.

His formal education in the arts began at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. During the 19th century, institutions like Miami University were expanding their curricula, and art instruction, though perhaps not as specialized as in dedicated academies, provided foundational skills. It was here that Evans would have likely received his initial training in drawing, perspective, and composition, essential building blocks for any aspiring painter. The environment of the American Midwest during this period was one of growth and cultural development, and artists like Evans were part of a generation seeking to establish a distinct American artistic identity, even as they looked to European traditions for guidance.

Forging a Career: Teaching and Further Study

After his studies at Miami University, De Scott Evans embarked on a career that combined artistic practice with teaching, a common path for many artists of his era. He initially taught in Cincinnati, Ohio, a significant cultural and artistic hub in the Midwest at the time. Cincinnati had a burgeoning art scene, with institutions like the McMicken School of Design (which later became the Art Academy of Cincinnati) fostering local talent. Artists such as Frank Duveneck and Henry Farny were associated with Cincinnati, contributing to its reputation as an "Athens of the West." Evans's time there would have exposed him to a community of artists and a public increasingly interested in art.

In 1873, Evans's pedagogical career took a significant step forward when he was appointed head of the art department at Mount Union College in Alliance, Ohio. This position not only provided him with a stable income but also affirmed his standing as a capable artist and educator. Leading an art department would have required him to be proficient in various aspects of art instruction, further honing his own understanding of technique and theory.

Despite his commitments in Ohio, the allure of larger artistic centers and the desire for advanced training eventually led Evans to seek further instruction. He moved to Cleveland, where he continued to teach and paint. However, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, including Thomas Eakins and Mary Cassatt, Evans recognized the importance of studying in Europe, particularly in Paris, which was then the undisputed capital of the art world.

Around 1877-1878, Evans traveled to Paris to study under the acclaimed academic painter Adolphe William Bouguereau at the Académie Julian. Bouguereau was one of the most famous and influential artists of his time, renowned for his highly polished, idealized depictions of mythological and genre subjects. Studying with Bouguereau would have immersed Evans in the rigorous academic tradition, emphasizing precise drawing, smooth brushwork, and careful modeling of form. This training profoundly influenced Evans's technique, particularly evident in the refined finish and meticulous detail of his subsequent work. Other American artists who studied with Bouguereau around this period included Robert Henri and Frederick Arthur Bridgman, highlighting the master's significant impact on American art.

Artistic Style: Realism, Refinement, and Trompe l'Oeil

Upon his return from Paris, De Scott Evans's artistic style was a sophisticated blend of American realism and French academic polish. He was a versatile painter, adept at several genres. His portraits, often of elegant women, captured the genteel atmosphere of the late Victorian era. These works are characterized by their delicate rendering of fabrics, sensitive portrayal of character, and a smooth, almost invisible brushwork that reflected his Parisian training. He had a particular talent for depicting the textures of silks, satins, and lace, adding to the overall sense of refinement in these compositions.

In his genre scenes, Evans often depicted moments of everyday life, sometimes with a narrative or sentimental quality popular at the time. Works like In the Studio or Mother's Treasure showcase his ability to create intimate and engaging compositions, drawing the viewer into the world of his subjects. These paintings demonstrate his skill in figure arrangement, interior lighting, and the creation of a specific mood or atmosphere.

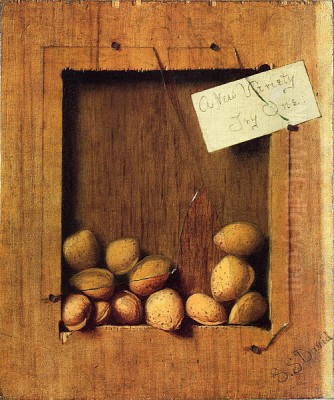

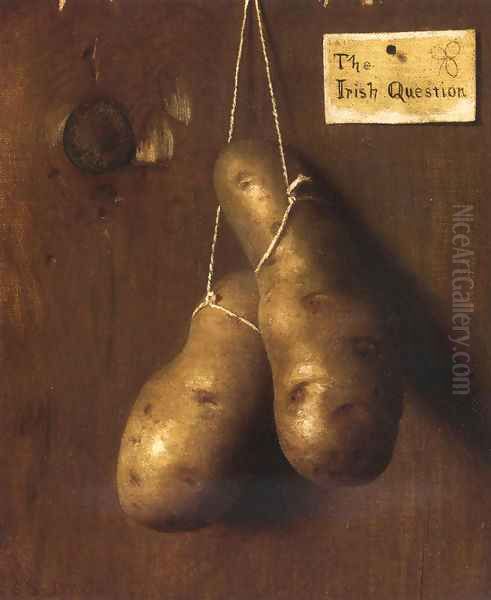

However, it is perhaps in the realm of still life, particularly his trompe l'oeil (French for "deceive the eye") paintings, that De Scott Evans made his most distinctive mark. Trompe l'oeil was a popular form of still life painting in America during the late 19th century, with artists like William Michael Harnett, John F. Peto, and John Haberle achieving considerable fame for their illusionistic canvases. Evans proved himself a master of this demanding genre. His trompe l'oeil works typically feature everyday objects—peanuts, almonds, fruit, or newspaper clippings—rendered with such startling realism that they appear to be actual objects resting on or projecting from the picture plane.

Interestingly, Evans often signed his trompe l'oeil paintings with pseudonyms such as "S.S. David," "David Scott," or "Stanley S. David." This practice may have been a way to distinguish these works, sometimes considered a more popular or less "serious" form of art by academic critics, from his more conventional portraits and genre scenes. It might also have been a playful nod to the deceptive nature of the paintings themselves or a strategy to navigate the art market more effectively. Regardless of the name attached, these works showcase his extraordinary technical skill and his keen observation of light, texture, and spatial relationships.

Masterworks and Thematic Concerns

Among De Scott Evans's most celebrated works is The Irish Question, painted in the 1880s. This trompe l'oeil still life depicts two potatoes seemingly suspended by strings against a wooden background, with a newspaper clipping referencing "The Irish Question"—a term widely used in the 19th century to describe the political and social turmoil in Ireland and its relationship with Great Britain, as well as the challenges faced by Irish immigrants in America. The painting is a marvel of illusionism; the potatoes appear so three-dimensional that one feels they could reach out and touch them. Beyond its technical brilliance, the work carries a layer of subtle humor and social commentary. The humble potato, a staple of the Irish diet and tragically linked to the Great Famine which spurred mass emigration, becomes a focal point for contemplation on a significant socio-political issue of the day. This work demonstrates Evans's ability to elevate the still life genre beyond mere technical display, infusing it with intellectual depth.

His other still life paintings, often featuring hanging fruit like apples or grapes, or arrangements of nuts, share this remarkable verisimilitude. For instance, his series of paintings depicting peanuts, sometimes shown loose, sometimes in a paper bag, are tour-de-forces of illusionistic painting. He meticulously rendered the crinkled texture of the shells, the subtle variations in color, and the play of light and shadow, creating an almost palpable sense of reality. These works align him with the aforementioned American trompe l'oeil specialists Harnett and Peto, who also favored depicting commonplace, often masculine-coded, objects.

In contrast to the often stark realism of his trompe l'oeil pieces, Evans's depictions of women, such as The Connoisseur or portraits of elegantly dressed ladies, showcase a softer, more polished academic style. These paintings reflect the era's ideals of femininity and domesticity, but also Evans's skill in capturing individual personality and the luxurious textures of fashionable attire. His handling of light in these interior scenes is often subtle and effective, contributing to the overall mood of quiet contemplation or genteel activity. These works can be seen in the tradition of American genre painters like Eastman Johnson, who also depicted scenes of American life, though Evans often brought a more overtly European academic finish to his figures.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

De Scott Evans worked during a dynamic period in American art. The late 19th century saw the rise of various artistic movements and a growing confidence among American artists. While Evans was deeply influenced by the academic tradition, particularly through Bouguereau, he was contemporary with artists exploring different paths.

The Hudson River School, with painters like Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church, had established a grand tradition of American landscape painting, though its dominance was waning by the time Evans was at his peak. Realism, however, was gaining prominence. Winslow Homer, with his powerful depictions of nature and human struggle, and Thomas Eakins, with his unflinching psychological portraits and scenes of modern life, were major figures who championed a distinctly American form of realism. While Evans's realism was often more polished and less gritty than Eakins's, he shared their commitment to truthful observation.

In Europe, Impressionism, led by artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, had revolutionized painting in the 1870s and 1880s. While Evans's style remained largely academic, the Impressionists' emphasis on light and contemporary subject matter had a widespread impact, and some American artists, like Mary Cassatt and Childe Hassam, fully embraced the new style. Evans, however, like his teacher Bouguereau or other French academic painters such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, remained committed to the principles of academic draftsmanship and finish.

The trompe l'oeil movement, in which Evans excelled, was a particularly American phenomenon in its late 19th-century iteration. William Michael Harnett was its most famous practitioner, creating intricate still lifes that fooled the eye and often carried symbolic meanings. John F. Peto, a contemporary and friend of Harnett, painted similar subjects but often with a more melancholic and less pristine quality. John Haberle was known for his incredibly detailed depictions of currency and everyday ephemera. Evans's contributions to this genre place him firmly within this fascinating sub-group of American realists. One might also consider the earlier American still life tradition of the Peale family, such as Raphaelle Peale, who also painted highly realistic still lifes, though with a different aesthetic.

Even an artist like Vincent van Gogh, a contemporary of Evans (Van Gogh died in 1890, Evans in 1898), was working in Europe during this period, though his expressive, post-Impressionist style was radically different from Evans's academic realism, highlighting the diverse artistic explorations occurring simultaneously.

Later Years and Tragic Demise

After his studies in Paris and his time teaching in Ohio, De Scott Evans eventually settled in New York City around 1887. New York had by then surpassed Boston and Philadelphia as the primary art center in the United States. It offered more opportunities for exhibition, patronage, and engagement with a vibrant artistic community. Evans continued to paint and teach, establishing a studio and presumably seeking to build his reputation in this competitive environment. His work from this period would have continued to reflect his established strengths in portraiture, genre scenes, and still life.

His career, however, was tragically cut short. In July 1898, De Scott Evans was a passenger aboard the French steamship SS La Bourgogne. He was likely traveling to Paris, perhaps to visit, exhibit, or seek further artistic inspiration. On July 4, 1898, in dense fog off Sable Island near Nova Scotia, La Bourgogne collided with the British sailing ship Cromartyshire. The liner sank rapidly, resulting in a devastating loss of life. Of the approximately 700 people on board, only around 170 survived. De Scott Evans was among the more than 500 passengers and crew who perished in the disaster. He was 51 years old.

His death was a significant loss to the American art world. While he had already produced a substantial body of work, one can only speculate on how his art might have evolved had he lived longer. His daughters later erected a monument in his memory at the Oxford Cemetery in Oxford, Ohio, a testament to his personal connections and the impact he had on those who knew him.

Legacy and Critical Reception

In the decades immediately following his death, De Scott Evans, like many academic painters of his generation, experienced a period of relative obscurity. The rise of Modernism in the early 20th century led to a shift in artistic tastes, and the highly finished, illusionistic styles of the late 19th century fell out of favor with many critics and collectors. Artists like Pablo Picasso or Henri Matisse were charting entirely new territories.

However, from the mid-20th century onwards, there has been a renewed appreciation for 19th-century American art, including the academic tradition and specialized genres like trompe l'oeil. Art historians began to re-evaluate artists like Evans, recognizing their technical skill, their role in reflecting the culture of their time, and their specific contributions to art history.

De Scott Evans is particularly remembered for his exceptional trompe l'oeil still lifes. These works are admired not only for their breathtaking illusionism but also for their clever compositions and, in cases like The Irish Question, their subtle wit and social resonance. His mastery in this genre places him among the foremost American trompe l'oeil painters. The use of pseudonyms for these works adds an intriguing layer to his biography, prompting discussion about artistic identity and the perceived hierarchy of genres in the 19th-century art world.

His portraits and genre scenes, while perhaps less distinctive than his trompe l'oeil work, are also valued for their technical proficiency and their depiction of late Victorian American life. They demonstrate his ability to work successfully within the prevailing academic standards of his time, creating images of elegance and refinement.

Today, De Scott Evans's paintings are held in the collections of numerous American museums, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Art Institute of Chicago, the Yale University Art Gallery, the Brandywine River Museum of Art, and the Butler Institute of American Art, among others. The inclusion of his work in these prestigious institutions affirms his significance. Exhibitions focusing on American realism or trompe l'oeil painting frequently feature his work, allowing contemporary audiences to experience the unique appeal of his art.

Conclusion

De Scott Evans stands as a significant figure in late 19th-century American art. His journey from rural Indiana to the art studios of Paris and the bustling art scene of New York reflects the ambitions and opportunities available to artists of his generation. Trained in the rigorous academic tradition, he developed a versatile style that allowed him to excel in portraiture, genre painting, and, most notably, trompe l'oeil still life. His meticulous technique, keen observational skills, and ability to imbue his subjects with both realism and a sense of wonder define his artistic contribution.

While his life was tragically cut short by the sinking of La Bourgogne, the body of work De Scott Evans left behind continues to captivate. His illusionistic paintings challenge our perceptions of reality and artifice, while his portraits and genre scenes offer a window into the refined sensibilities of Victorian America. As an artist who skillfully navigated different genres and even artistic personas through his use of pseudonyms, De Scott Evans remains a fascinating subject for study, a testament to the rich diversity of American artistic expression in an era of profound cultural and social change. His legacy endures in the canvases that continue to deceive the eye and delight the mind.