Claude Raguet Hirst (1855-1942) stands as a distinctive figure in the landscape of American art, particularly celebrated for her mastery of the trompe-l'oeil still life genre during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In a period largely dominated by male artists, Hirst carved out a unique niche, creating meticulously detailed paintings that not only deceived the eye with their hyperrealism but also subtly challenged conventional gender roles and artistic themes. Her work, often small in scale yet immense in its precision and suggestive power, offers a fascinating window into the artistic currents of her time and the evolving position of women within the art world.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1855, Claudine Raguet Hirst (she later adopted "Claude," a name ambiguous in gender, which may have been a strategic choice in a male-dominated field) grew up in a city with a burgeoning arts scene. Cincinnati was, at the time, a significant cultural hub in the American Midwest. Hirst's initial artistic inclinations led her to enroll at the Cincinnati School of Design, later known as the Art Academy of Cincinnati. This institution was notable for its progressive approach, including its encouragement of female students, a somewhat uncommon stance for the era.

During her studies in Cincinnati, she would have been exposed to a curriculum that likely emphasized academic drawing and painting. The city's artistic environment was also influenced by figures like Frank Duveneck and Henry Farny, who, though known for different styles (Duveneck for his Munich School realism and Farny for his depictions of Native Americans), contributed to a rich local artistic dialogue. Another prominent female artist from Cincinnati, Elizabeth Nourse, who achieved international acclaim, was a near contemporary and also studied at the McMicken School of Design (an earlier name for the Art Academy), showcasing the city's capacity to nurture female talent. Hirst's foundational training here would have equipped her with the technical skills necessary for her later, highly detailed work.

New York and the Embrace of Trompe-l'oeil

In 1879, seeking broader opportunities and a more dynamic artistic environment, Hirst made the pivotal decision to move to New York City. This relocation placed her at the heart of the American art world, offering exposure to a wider range of influences, galleries, and fellow artists. It was in New York that she continued her artistic education, though specific details of her tutelage there are less extensively documented than her Cincinnati period. However, it is widely acknowledged that her artistic direction significantly shifted and matured in this new setting.

The late 19th century in America saw a flourishing of trompe-l'oeil ("deceive the eye") painting, a genre that aimed to create such convincing illusions of reality that viewers might mistake the painted objects for real ones. The undisputed master of this style was William Michael Harnett, whose meticulously rendered still lifes of everyday objects, often with a masculine character—pipes, books, tankards, and hunting gear—were immensely popular. Harnett’s work, along with that of his contemporaries like John F. Peto and John Haberle, set a high standard for illusionistic painting.

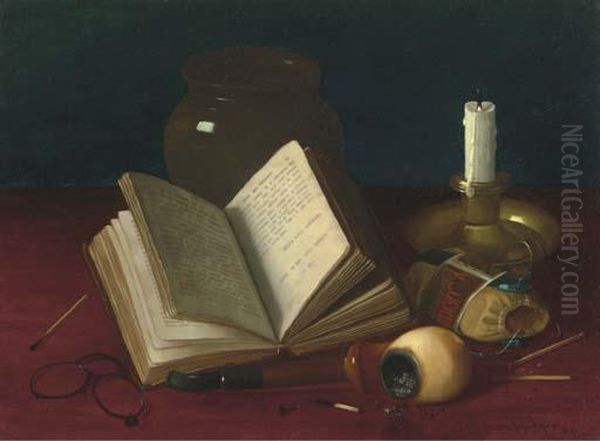

Hirst was undoubtedly influenced by this prevailing trend and particularly by Harnett's bachelor still-life compositions. She began to specialize in still life, initially painting more conventional subjects like fruit and flowers. However, she soon gravitated towards the detailed, illusionistic style that would define her career, focusing on arrangements of books, pipes, inkwells, eyeglasses, and other scholarly or masculine-associated paraphernalia.

The Art of Deception: Hirst's Trompe-l'oeil Technique

Claude Raguet Hirst’s commitment to the trompe-l'oeil aesthetic was profound. Her paintings are characterized by an extraordinary level of detail, a precise rendering of textures, and a sophisticated understanding of light and shadow to create a convincing sense of three-dimensionality. She typically worked on a small scale, which perhaps intensified the jewel-like quality of her compositions and allowed for an almost microscopic attention to detail. Whether working in watercolor or oil, Hirst achieved a remarkable verisimilitude. Critics often noted that her watercolors possessed the richness and depth typically associated with oil paintings, a testament to her technical skill.

Her compositions often feature objects arranged on a wooden tabletop, frequently a polished surface that would reflect the items placed upon it, adding another layer of illusion. The edges of books appear worn, pages slightly curled, leather bindings showing scuffs and age. The metallic sheen of a pipe cleaner, the glint of light on eyeglasses, the subtle texture of a tobacco pouch—all were rendered with painstaking care. This dedication to realism invited viewers to scrutinize her work closely, to marvel at the illusion, and perhaps even to reach out and touch the painted objects. This interactive quality is a hallmark of successful trompe-l'oeil.

Themes and Subject Matter: A Unique Blend

While Hirst adopted the masculine-coded objects prevalent in the still lifes of Harnett and his followers, her approach contained subtle but significant differences and undercurrents. Her arrangements, though often featuring pipes, tobacco, and old books, sometimes felt less like a casual bachelor’s clutter and more like carefully curated collections, hinting at intellectual pursuits and quiet contemplation.

A particularly noteworthy aspect of Hirst's oeuvre is her frequent inclusion of books, often with legible titles or even open to specific pages. This was not merely a compositional device; it often carried symbolic weight. She was known to depict books by early progressive female writers, such as Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1523-1673), a pioneering philosopher, poet, and playwright. By including such works, Hirst was subtly inserting a female intellectual presence into a traditionally male genre, thereby making a quiet statement about women's contributions to literature and thought, and perhaps aligning herself with the burgeoning feminist sentiments of her era. This act of curating specific texts within her paintings adds a layer of intellectual depth and personal conviction to her work.

Her choice of subject matter can be seen as a strategic negotiation. By painting objects associated with male domains, she could appeal to male patrons and critics, gaining entry into an art world that might have been less receptive to more traditionally "feminine" subjects from a female artist aiming for serious recognition. Yet, within this framework, she found ways to express her own perspective and subtly challenge expectations.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of Hirst's paintings exemplify her skill and thematic concerns.

A Gentleman’s Table (various versions): This title, or variations thereof, was used for several compositions. These works typically depict a tabletop arrayed with books, a pipe, perhaps a newspaper or matches, and sometimes a piece of fruit or a small vase of flowers, blending the masculine with a hint of domesticity or traditional still life elements. The meticulous detail in the rendering of book bindings, the texture of tobacco, and the play of light across different surfaces is characteristic.

Roses: While known for her "masculine" still lifes, Hirst also painted floral subjects, particularly roses. These works, like Roses (c. 1890s), demonstrate her versatility and her ability to capture the delicate beauty of flowers with the same precision she applied to books and pipes. The velvety texture of the petals and the subtle gradations of color showcase her mastery of her chosen medium.

A Book of Letters (featuring Margaret Cavendish): This work is a prime example of Hirst’s engagement with female intellectual history. By prominently featuring a book by Cavendish, Hirst highlights a significant female author from a much earlier period, creating a dialogue across centuries and underscoring the enduring value of women's literary contributions.

Book Closed Over Spectacles (c. 1890s, Philadelphia Museum of Art): This intimate composition focuses on a closed book with a pair of spectacles resting on top, suggesting a pause in reading or study. The simplicity of the arrangement belies the complexity of the execution, with the textures of the book cover and the reflective quality of the lenses rendered with Hirst's signature precision. It evokes a sense of quiet intellectual activity.

An Interesting Book (1890, Canton Museum of Art, Guangzhou): The title itself invites curiosity. Such works often depicted well-worn volumes, their pages perhaps slightly dog-eared, hinting at a beloved text that has been read and re-read. The focus is on the book as an object of intellectual engagement and personal significance.

These works, and many others, demonstrate Hirst's consistent dedication to her craft and her unique thematic blend. She produced over 100 still life paintings throughout her career, each a testament to her meticulous approach.

Artistic Style in Context: American Realism and Still Life

Hirst’s work is firmly rooted in the broader movement of American Realism that gained prominence in the latter half of the 19th century. Artists like Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer were celebrated for their unvarnished depictions of American life and landscape. While Hirst’s focus was narrower, her commitment to verisimilitude aligns with this realist impulse. The trompe-l'oeil tradition itself can be seen as an extreme form of realism, pushing the boundaries of illusion.

The American still life tradition has a long history, dating back to colonial painters like James Peale and Raphaelle Peale, who established the genre in the young nation. By the mid-19th century, artists like Severin Roesen were known for their abundant and opulent fruit and flower still lifes. Hirst’s work, however, aligns more closely with the "desk-top" or "bachelor" still lifes popularized by Harnett, which often featured more personal, everyday objects rather than purely decorative arrangements.

Hirst’s decision to sometimes use her first name as "Claude" rather than "Claudine" is also telling. This ambiguity could have helped her navigate an art world where female artists often faced prejudice or were relegated to "lesser" genres. Other female artists of the period, such as Mary Cassatt and Cecilia Beaux, achieved significant success, but often by studying and exhibiting abroad, or by focusing on portraiture and scenes of domestic life, which were considered more acceptable for women. Hirst’s engagement with the masculine-coded trompe-l'oeil still life was a less common path. Lilly Martin Spencer, an earlier 19th-century American artist, also from Ohio, had successfully navigated a career painting genre scenes, often with a focus on domesticity, but faced constant financial struggles despite her popularity, highlighting the precariousness of a woman's artistic career.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Life

Claude Raguet Hirst began to gain recognition for her work in the 1880s and 1890s. She exhibited regularly at prestigious venues, including the National Academy of Design in New York, where her work was first shown in 1884 (though some sources state 1897 for a significant exhibition). Her paintings were admired for their technical brilliance and the intriguing quality of their illusionism. Critics often praised her meticulous detail and the lifelike appearance of her subjects.

Her works found their way into various collections. The Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio has played a significant role in preserving and promoting her legacy, notably through the exhibition "Claude Raguet Hirst: Transforming the American Still Life." This exhibition brought together around 30 of her works, highlighting her unique contribution. Her paintings are also held in the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Canton Museum of Art in Guangzhou, China (a testament to an early international interest or acquisition), and the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, among others. The Petteys Collection of Women Artists also includes her work, underscoring her importance as a female artist. Hawthorne Fine Art and William Vareika Fine Arts have also featured her works, indicating continued interest in the private market.

Despite achieving a degree of professional success and recognition during her lifetime, Hirst, like many artists, faced challenges, particularly in her later years. As artistic tastes shifted in the early 20th century with the advent of Modernism, the popularity of highly detailed, illusionistic realism waned. Hirst continued to paint in her established style, but the art world's focus was moving elsewhere. She reportedly fell into poverty towards the end of her life. Claude Raguet Hirst passed away in New York City in 1942. It is noted that an art association paid for the preservation of her remaining works, a poignant acknowledgment of her artistic contributions even as she faced personal hardship.

Enduring Legacy

Claude Raguet Hirst’s legacy is multifaceted. She was a highly skilled practitioner of trompe-l'oeil painting, a demanding genre that required immense patience and technical prowess. Her ability to create convincing illusions with such finesse places her among the notable figures of this American artistic tradition, alongside more widely known names like Harnett, Peto, and Haberle.

Perhaps more significantly, Hirst stands out as one of the few women to achieve prominence in this particular niche of still life painting. Her work subtly subverted gender norms by adopting masculine-coded subjects while simultaneously infusing them with a nuanced, often intellectual, and sometimes quietly feminist perspective. Her inclusion of books by female authors is a particularly compelling aspect of her oeuvre, suggesting a thoughtful engagement with themes of gender and intellectual heritage.

In recent decades, there has been a renewed scholarly and curatorial interest in the work of historical women artists who were overlooked or marginalized by earlier art historical narratives. Claude Raguet Hirst is among those whose contributions are being re-evaluated and celebrated. Her paintings are not merely technical marvels; they are thoughtful, intricate compositions that offer insights into the cultural and social dynamics of her time, and the quiet determination of a woman artist to make her mark in a challenging world. Her work continues to fascinate viewers with its deceptive realism and its subtle, layered meanings, securing her place as an important and intriguing figure in American art history. Her teacher, John Noble, and contemporaries like George Inness (though more of a Tonalist and landscape painter) or Eastman Johnson (genre scenes and portraits) represent the broader artistic milieu from which she emerged and distinguished herself with her unique focus.

Conclusion

Claude Raguet Hirst's journey from Cincinnati to the competitive art scene of New York, her mastery of the demanding trompe-l'oeil technique, and her unique thematic choices mark her as a significant artist of her era. She navigated a male-dominated art form with skill and subtlety, creating works that continue to intrigue and impress. Her meticulous still lifes, often featuring books, pipes, and other accoutrements of intellectual life, are more than just dazzling displays of technical skill; they are windows into a contemplative world, subtly infused with her own perspectives on gender, intellect, and the enduring power of art to both deceive and reveal. As art history continues to broaden its scope to more fully recognize the contributions of artists from diverse backgrounds, Claude Raguet Hirst's unique vision and quiet resilience ensure her an enduring place in the story of American art.