George Cope (1855-1929) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in late 19th and early 20th-century American art. Primarily celebrated for his exceptional skill in the art of trompe l’oeil still life, Cope carved a niche for himself with meticulously detailed paintings that captivated audiences and continue to intrigue art historians and enthusiasts alike. His journey from a landscape painter to a master of illusionistic still life reflects both personal artistic evolution and broader trends in American art during a period of burgeoning national identity and artistic exploration.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born near the pastoral surroundings of West Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1855, George Cope's artistic inclinations were apparent from an early age. It is said that he inherited a natural talent for drawing and painting from his mother, providing an initial, informal grounding in the arts. While largely self-taught, a crucial step in his formal artistic development came when he sought instruction in oil painting techniques. His mentor was the German-born American painter Herman Herzog (1832-1932), a respected artist known for his dramatic landscapes and seascapes, often imbued with a romantic sensibility influenced by the Düsseldorf school.

Under Herzog's tutelage, Cope would have been exposed to rigorous training in observation and the technical aspects of oil painting. Herzog himself was a prolific painter who had achieved success in Europe before emigrating to the United States, eventually settling in Philadelphia. His influence on Cope likely instilled a strong foundation in traditional painting methods and an appreciation for the natural world, which would initially manifest in Cope's own landscape works.

During the early phase of his career, Cope dedicated himself to landscape painting. This was a popular genre in America at the time, dominated by the Hudson River School artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand in the preceding generation, and later figures who continued to explore the American wilderness. Cope's landscapes, though less documented than his later still lifes, would have reflected the prevailing taste for depictions of American scenery, likely focusing on the lush environments of his native Pennsylvania.

The Pivotal Shift to Still Life

A significant turning point in George Cope's artistic trajectory occurred around the mid-1880s. It was during this period that he began to transition away from landscape painting and towards the genre of still life. This shift was not merely a change in subject matter but a profound reorientation of his artistic focus, leading him to the specialized and demanding field of trompe l’oeil. The reasons for this change are not definitively recorded, but it could have been influenced by a desire for a new artistic challenge, the growing popularity of trompe l'oeil in America, or the potential for a more distinctive market niche.

The American art scene in the late 19th century saw a remarkable flourishing of trompe l'oeil still life painting. Artists like William Michael Harnett (1848-1992) were achieving considerable fame and notoriety for their incredibly deceptive paintings of everyday objects. Harnett, often considered the leading figure of this movement, created compositions featuring items like books, musical instruments, currency, and hunting gear, all rendered with such precision that viewers were tempted to reach out and touch them. His success undoubtedly inspired many contemporaries.

Other notable practitioners in this highly realistic vein included John F. Peto (1854-1907), whose works often had a more melancholic and worn quality compared to Harnett's crisp precision, and John Haberle (1856-1933), known for his meticulous depictions of currency and his playful, almost audacious, challenges to the viewer's perception. It was within this exciting and competitive environment that Cope began to develop his own unique approach to still life.

Mastering the Art of Deception: Cope's Trompe l'oeil Technique

George Cope quickly distinguished himself in the realm of trompe l’oeil. His still lifes often featured themes that resonated with a masculine, late-Victorian American sensibility: hunting equipment, fishing tackle, and the spoils of the hunt. These subjects were popular, evoking a sense of rugged individualism and a connection to the outdoors. Cope's particular genius lay in his ability to render these objects with an astonishing degree of verisimilitude.

A hallmark of Cope's trompe l'oeil works is his meticulous attention to texture, particularly the grain of wood. Many of his compositions depict objects—often game birds, rifles, powder horns, or fishing rods—hanging against a wooden background, such as a door or a plank wall. Cope rendered the knots, whorls, and striations of the wood with such fidelity that the painted surface itself seemed to become the actual material. This emphasis on the background as an integral, illusionistic element of the composition was a key feature of his style.

His arrangements were typically focused and centralized, with objects carefully placed to maximize their three-dimensional effect. Unlike some trompe l'oeil artists who created complex, almost cluttered compositions, Cope often favored a more direct and concentrated presentation. While his work might sometimes lack the dramatic chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) seen in artists like Harnett, the sheer photographic realism and the tactile quality of his surfaces were compelling in their own right. He also explored what were described as "Babylonian style" and "Indian themes," suggesting an interest in exotic or historical objects, though his hunting and fishing scenes remain his most recognized contributions.

Themes and Subjects in Cope's Art

The recurring themes in George Cope's mature work provide insight into the cultural interests of his time and his personal artistic preferences. His "rack pictures" or "hanging game" still lifes are particularly noteworthy. These paintings typically show game birds, such as ducks or woodcock, suspended from a nail or hook against a wooden surface, often accompanied by hunting paraphernalia like shotguns, powder flasks, and hunting horns. These compositions were not merely displays of technical skill; they also tapped into a nostalgic appreciation for rural life and sporting traditions that were increasingly being romanticized as America became more urbanized and industrialized.

Fishing subjects were another favorite. Paintings depicting fishing rods, reels, creels, and freshly caught fish, again often set against a convincing wooden backdrop, appealed to a similar demographic of sportsmen and nature enthusiasts. The precision with which Cope rendered the scales of a fish, the sheen of a fishing line, or the texture of a wicker creel was remarkable.

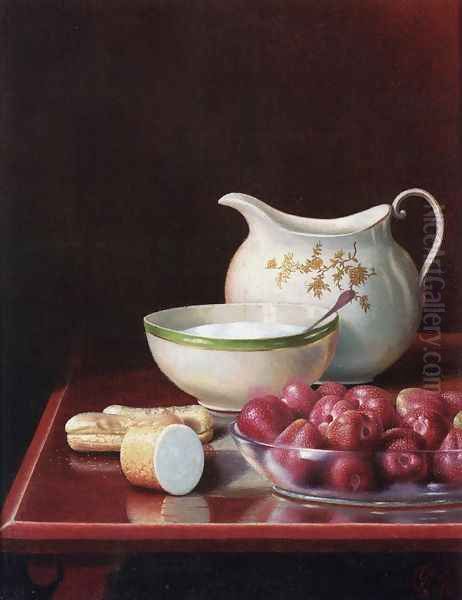

Beyond these sporting themes, Cope also painted still lifes featuring more domestic or everyday objects. One of his known works, Still Life with Berries, Sugar, and Cream Pitcher (1916), demonstrates his versatility within the still life genre. This painting showcases his ability to capture the delicate translucency of berries, the granular texture of sugar, and the smooth, reflective surface of a ceramic pitcher, all rendered with his characteristic precision and careful attention to color and light. Such works connect him to a longer tradition of tabletop still life painting, reminiscent of the detailed compositions of 17th-century Dutch masters like Willem Claesz. Heda or Pieter Claesz, though filtered through a distinctly American lens.

Life in West Chester and Later Career

In 1883, George Cope made the decision to return to his hometown of West Chester, Pennsylvania. He would spend the remainder of his life there, establishing himself not only as a painter but also as an art teacher and a restorer of paintings. This multifaceted career provided him with a steady livelihood and allowed him to remain deeply connected to his local community. His studio or shop, reportedly located on Channcey Avenue, became something of a local cultural landmark, a place where his works could be viewed and purchased, and where he shared his artistic knowledge.

His reputation, particularly for his trompe l'oeil still lifes, grew, and he found favor among collectors, especially in Philadelphia and its surrounding affluent areas. The demand for highly realistic and illusionistic paintings was strong, and Cope's work, with its combination of technical brilliance and appealing subject matter, fit well within this market. His role as a restorer also speaks to his technical understanding of paint and canvas, skills that would have undoubtedly informed his own painting practice.

While West Chester might not have been a major art center like Philadelphia or New York, it provided Cope with a stable environment in which to pursue his art. His connection to the local landscape and its sporting traditions likely continued to inform his choice of subject matter. He remained active as an artist until his death in 1929.

Notable Works and Collections

George Cope's paintings, prized for their meticulous realism, found their way into numerous private collections during his lifetime and have since been acquired by several prestigious public institutions. This posthumous recognition underscores his lasting contribution to American art.

Among his representative works, paintings like Hanging Woodcock exemplify his skill in rendering game birds and the illusion of textured wood. The anecdote that viewers might mistake the painted wood grain for actual timber is a testament to his success in the trompe l'oeil technique. His various depictions of hunting trophies, fishing gear, and other arrangements of objects continue to be studied for their technical mastery. Still Life with Berries, Sugar, and Cream Pitcher (1916) is another important example, showcasing his abilities beyond the typical masculine themes of his hunting still lifes.

Today, George Cope's works are held in the collections of prominent museums, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which has a strong collection of works by Pennsylvania artists. The Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, known for its focus on American art, particularly that of the Brandywine Valley, also holds examples of his work, fitting given Cope's regional connections. Furthermore, his paintings can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Pennsylvania State University Art Museum, and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, which has a historically significant collection of American trompe l'oeil.

Cope in the Context of American Art and Contemporaries

George Cope's artistic career unfolded during a dynamic period in American art. While he was not part of avant-garde movements like Impressionism that were taking hold in Europe and gradually influencing American artists like Mary Cassatt or Childe Hassam, Cope excelled within the established tradition of realism, particularly its illusionistic variant.

His primary artistic lineage connects him directly to William Michael Harnett. Cope was clearly influenced by Harnett's success and adopted similar themes and the trompe l'oeil approach. However, Cope developed his own distinct style, often characterized by a slightly brighter palette and a less cluttered, more direct compositional arrangement than some of Harnett's more elaborate "tabletop" or "letter rack" paintings. He shared the trompe l'oeil stage with John F. Peto, whose works often evoke a greater sense of nostalgia and the passage of time through the depiction of worn and discarded objects, and John Haberle, whose meticulous renderings of currency famously drew the attention of the Secret Service.

It's interesting to consider Cope's relationship with other contemporaries. The provided information mentions a possible collaboration with a British painter named Charles West Cope (1811-1890), who was a Victorian-era historical and genre painter. If this Charles West Cope was indeed his brother (though the age difference and nationality make this seem less likely unless there's a different Charles Cope), it would suggest familial artistic connections. However, the more prominent Charles West Cope was a well-established figure in the British Royal Academy. More research would be needed to clarify this connection.

The mention of Cope imitating J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), the great British Romantic landscape painter, is intriguing. If Cope, in his earlier landscape phase or even later, attempted works in Turner's dramatic and atmospheric style, it would indicate a broad range of artistic interests and perhaps a competitive spirit, aiming to emulate one of the giants of landscape art. This would contrast sharply with the precise, almost microscopic detail of his later still lifes.

Cope's dedication to realism placed him in a stream of American art that valued verisimilitude and craftsmanship, a tradition that includes earlier figures like the Peale family (Charles Willson Peale, Raphaelle Peale, James Peale), who were pioneers of American still life, and later 19th-century realists working in various genres. While the trompe l'oeil movement itself was somewhat niche, its emphasis on skill and illusion had wide appeal.

Anecdotes and Artistic Persona

The anecdotes surrounding George Cope's work, such as the story of his Hanging Woodcock deceiving viewers with its wood grain, are typical of the lore that often accompanies successful trompe l'oeil artists. Such stories enhanced their reputations and highlighted the "magical" quality of their art. The very nature of trompe l'oeil invites such tales, as the artist's goal is to playfully trick the audience.

His shop in West Chester becoming a local cultural landmark suggests an artist who was accessible and integrated into his community, rather than an isolated figure. This local presence, combined with his success with Philadelphia collectors, paints a picture of a respected professional.

The mention of humor and satire in his work, possibly exemplified by illustrations or works referencing publications like Harper's Weekly, adds another dimension to his artistic personality. Trompe l'oeil itself can have an inherent humor in its playful deception, and if Cope incorporated narrative or satirical elements, it would align him with artists like Haberle, who sometimes embedded witty commentary in his detailed compositions.

Legacy and Lasting Influence

George Cope's primary legacy lies in his contribution to the American trompe l'oeil movement. While perhaps not as widely known today as Harnett or Peto, his work is consistently recognized for its technical excellence and its distinct thematic focus, particularly on hunting and fishing subjects. He successfully captured a specific aspect of American culture and taste in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

His paintings serve as important documents of the material culture of the era, from the design of firearms and fishing equipment to the types of game pursued. Beyond their subject matter, they stand as testaments to the enduring appeal of illusionistic art and the high level of craftsmanship achieved by American painters in this period.

The inclusion of his works in major museum collections ensures that his art continues to be seen and appreciated by new generations. For art historians, Cope's paintings offer valuable insights into the nuances of the American trompe l'oeil school, demonstrating the variations in style and subject matter among its practitioners. He was not merely an imitator of Harnett but an artist who developed a personal and recognizable approach to the genre.

While he may not have been involved in specific, named art groups or organizations in the way some artists affiliate with formal societies, his participation in the broader trompe l'oeil "movement" or trend is undeniable. This was less a formal group and more a shared artistic interest among a number of highly skilled individuals who responded to a public fascination with illusionism.

Conclusion

George Cope was a dedicated and highly skilled American painter who found his true artistic voice in the demanding genre of trompe l'oeil still life. From his early training with Herman Herzog and his initial forays into landscape painting, he evolved into a master of illusion, creating works that delighted and astonished his contemporaries. His meticulous renderings of hunting trophies, fishing gear, and other subjects, often set against uncannily realistic wooden backgrounds, secured him a place in the annals of American art.

His life in West Chester, as both an artist and a teacher, demonstrates a commitment to his craft and his community. While the grand narratives of art history often focus on radical innovators, artists like George Cope, who achieved excellence within established traditions and specialized genres, play a crucial role in creating a rich and diverse artistic landscape. His paintings remain a testament to the power of realistic representation and the enduring human fascination with art that skillfully blurs the line between the painted image and the real world. George Cope's legacy is preserved in the quiet, compelling illusionism of his canvases, inviting viewers to look closely and marvel at the artist's deceptive hand.