John Frederick Peto (1854–1907) stands as a significant yet historically complex figure in American art. Primarily celebrated for his mastery of still life painting, particularly in the trompe l'oeil (fool the eye) style, Peto crafted a body of work distinct for its quiet melancholy, focus on humble objects, and painterly texture. Though often overshadowed during his lifetime by his contemporary William Michael Harnett, Peto's unique artistic voice and contribution to American realism have earned him considerable posthumous recognition. His paintings, often depicting worn books, musical instruments, and cluttered office boards, offer poignant reflections on time, memory, and the beauty found in the everyday.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Philadelphia

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 21, 1854, John F. Peto came of age in a city with a burgeoning artistic identity. Philadelphia was home to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), one of the oldest and most prestigious art institutions in the United States. It was within this environment, which fostered talents like Thomas Eakins and, for a time, Mary Cassatt, that Peto sought his artistic education.

In 1878, Peto enrolled at PAFA, immersing himself in the academic training available. The Academy provided rigorous instruction in drawing and painting, emphasizing observation and technical skill. During his time there, Peto began exhibiting his work, participating regularly in PAFA's annual exhibitions between 1879 and 1886. These early showings helped establish him within the local art scene, though widespread fame remained elusive. It was also during this period that he formed a crucial, lifelong connection with fellow student William Michael Harnett.

The Shadow and Light of William Michael Harnett

The relationship between John F. Peto and William Michael Harnett (1848–1892) is central to understanding Peto's career and reception. Both artists were drawn to the meticulous realism of trompe l'oeil still life, a genre experiencing a revival in late 19th-century America. They were friends and shared studio space for a time, undoubtedly influencing each other's development. Harnett, however, achieved significant commercial success and critical acclaim during his lifetime, becoming the most famous practitioner of the style.

Despite their shared interest, distinct differences emerged in their approaches. Harnett's work often featured arrangements of more luxurious or distinctly masculine objects – gleaming tankards, pipes, hunting gear, crisp currency – rendered with sharp focus and a smooth, almost invisible brushstroke. His compositions were meticulously ordered, emphasizing the illusionistic potential of painting to mimic reality precisely.

Peto, conversely, gravitated towards more commonplace, often worn and discarded items: tattered books, aging photographs, dented musical instruments, forgotten letters. His handling of paint was generally softer, his light more diffused and atmospheric, and his textures more tactile and painterly. While Harnett aimed for crystalline clarity, Peto often imbued his subjects with a sense of pathos and the quiet dignity of age. This difference led to Peto's work being perceived as more personal and melancholic. The stylistic similarities, however, coupled with Harnett's fame, led to confusion, with some unscrupulous dealers later forging Harnett's signature onto Peto's canvases to increase their value.

Peto's Unique Vision: Style and Technique

John F. Peto developed a highly personal style within the trompe l'oeil tradition. While capable of rendering objects with convincing realism, his focus often seemed less on pure deception and more on evoking the presence and history of the objects themselves. His brushwork, unlike Harnett's polished finish, could be more visible, sometimes employing a thicker application of paint (impasto) to convey the rough texture of worn leather, the crumbling edge of paper, or the dull gleam of aged metal.

Light plays a crucial role in Peto's paintings, but it is often a soft, enveloping light rather than the harsh, clarifying light sometimes seen in Harnett's work. This contributes to the quiet, introspective mood characteristic of Peto's best paintings. He demonstrated a profound sensitivity to the way light interacts with different surfaces, capturing the subtle variations in tone and color that give objects their weight and form.

His fascination with texture is paramount. Peto seemed drawn to the evidence of use and the passage of time etched onto surfaces. Dog-eared book pages, cracked bindings, faded photographs, tarnished brass – these were not imperfections to be glossed over but essential elements of the object's character and narrative. This focus on the worn and weathered distinguishes his work not only from Harnett but also from other American trompe l'oeil specialists like John Haberle, known for his incredibly precise depictions of currency and stamps.

Themes of Time, Memory, and the Everyday

Peto's choice of subject matter reinforces the distinctive themes that run through his work. He repeatedly returned to motifs that spoke of intellectual life, domesticity, the passage of time, and mortality, often tinged with a gentle melancholy.

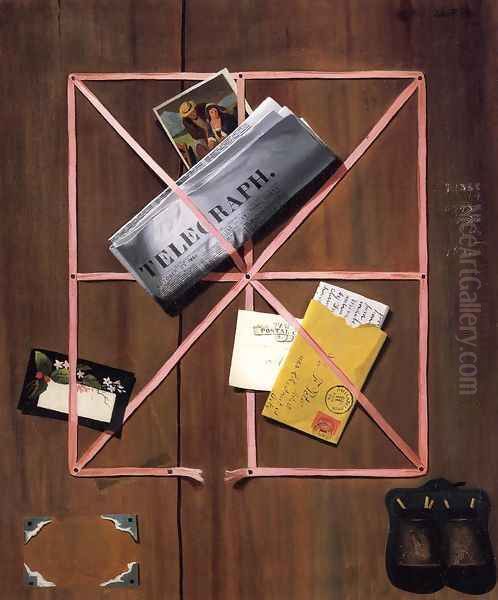

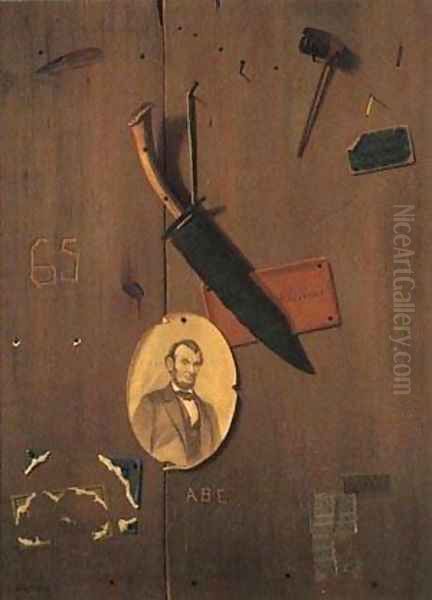

Rack Pictures: Among Peto's most iconic works are his "rack pictures." These paintings depict shallow wooden racks or bulletin boards crisscrossed with tapes, holding an assortment of letters, postcards, newspaper clippings, photographs, and other ephemera. These compositions are masterful illusions, appearing as casual accumulations of everyday items. They often contain subtle narratives or references, sometimes including images of figures like Abraham Lincoln, adding layers of historical or personal meaning. The objects seem pinned in a moment, yet their aged appearance speaks volumes about time passing.

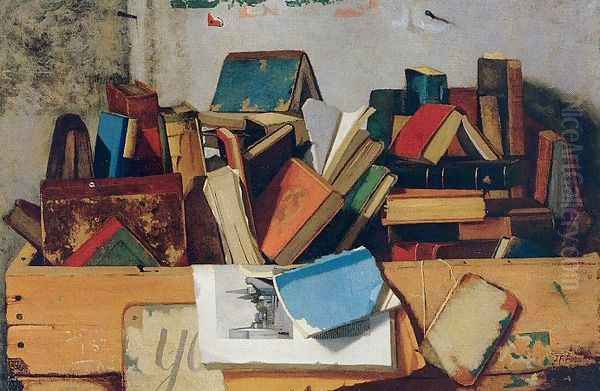

Books: Books are perhaps the most frequent subject in Peto's oeuvre. He depicted them stacked, open, closed, often showing signs of heavy use – worn covers, broken spines, loose pages. These are not pristine collector's items but objects integrated into daily life, suggesting knowledge, reflection, and the enduring power of the written word, while simultaneously reminding the viewer of their physical vulnerability to decay.

Musical Instruments: Peto often painted musical instruments, particularly violins and cornets. This likely reflected his personal interest – he was known to play the trombone. These objects, associated with the ephemeral art of music, add another layer to his exploration of time and memory. An instrument might lie silent, perhaps hinting at music once played or a talent now dormant.

Vanitas Elements: While not always overt, Peto's work resonates with the historical vanitas tradition, exemplified by Dutch Golden Age masters like Pieter Claesz or Willem Kalf. The emphasis on worn, decaying objects, the frequent inclusion of items related to fleeting pleasures (like smoking pipes, though less common than in Harnett), and the overall sense of time's relentless march subtly remind the viewer of the transience of life and material possessions.

Masterworks in Focus

Several paintings stand out as representative of Peto's style and thematic concerns:

The Old Cremona (c. 1880s-90s): This title, used for several variations, typically depicts an aged violin, often hanging against a wooden door or wall, sometimes accompanied by a bow, sheet music, or other small objects. The focus is on the rich, warm tones of the wood, the evidence of wear on the instrument's surface, and the play of soft light. These paintings evoke a sense of quiet nostalgia and the beauty inherent in well-used objects.

Rack Pictures (Various): Works like Office Board for Smith Brothers Coal Company or Rack Picture with Telegraph Letter exemplify this genre. They showcase Peto's skill in arranging complex compositions within a shallow space and his ability to render diverse textures – paper, wood, string, metal – with convincing realism. Each element seems carefully chosen, contributing to an overall narrative or mood, often reflecting the mundane yet meaningful details of business or personal correspondence.

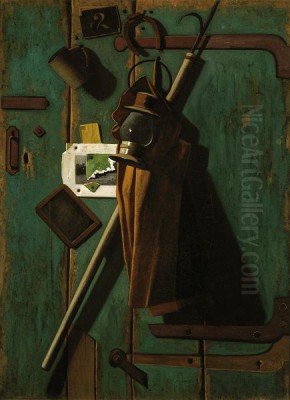

Market Basket, Hat, and Umbrella (c. 1900): This later work shows a simple arrangement of everyday items against a plain background. The composition is straightforward, yet the objects possess a quiet dignity. The textures of the woven basket, the felt hat, and the fabric of the umbrella are rendered with Peto's characteristic sensitivity. It reflects his continued interest in the humble objects of daily life.

Take Your Choice (c. 1885): This painting, featuring coins seemingly scattered on a surface, directly engages the viewer with its trompe l'oeil premise. The title invites interaction, playing on the illusionistic nature of the medium. It highlights the element of visual wit present in the trompe l'oeil tradition.

Island Heights: A Life Apart

In 1887, Peto married Christine Pearl Smith. Seeking a quieter life away from the competitive Philadelphia art world, the couple moved to the small resort town of Island Heights, New Jersey, on the Toms River, in 1889. There, Peto built a house and studio, which would remain his base for the rest of his life. This move marked a significant shift, distancing him from major art centers and potentially contributing to his relative obscurity during his later years.

Life in Island Heights was centered around his family, his painting, and his community involvement, which included playing the trombone at the local Methodist camp meetings. His studio, filled with the props and objects that appear in his paintings, became his sanctuary. This environment, preserved today as the John F. Peto Studio Museum, offers invaluable insight into his working methods and the world he inhabited. While perhaps isolating him professionally, the Island Heights period allowed Peto to focus intently on his art, further developing his personal style away from the direct influence of the urban art market. He continued to paint prolifically, though often supplementing his income through less prestigious means, such as coloring photographs or painting house signs.

The Allure of Illusion: Trompe l'oeil in Context

The trompe l'oeil style Peto practiced has a long and fascinating history. Ancient Greek legends tell of painters like Zeuxis, whose painted grapes supposedly fooled birds, and Parrhasius, whose painted curtain deceived Zeuxis himself. The technique saw revivals during the Renaissance, with artists like Andrea Mantegna incorporating illusionistic elements into frescoes, and particularly during the Dutch Golden Age, where artists like Samuel van Hoogstraten created intricate "quodlibet" paintings resembling tacked-up letters and objects.

In late 19th-century America, trompe l'oeil experienced a remarkable surge in popularity. Artists like Harnett, Peto, and Haberle captured the public imagination with their uncanny realism. This coincided with a period of industrial growth, materialism, and fascination with verisimilitude, perhaps fueled by the advent of photography. These paintings, often depicting objects associated with American life – currency, newspapers, firearms, everyday tools – resonated with a wide audience.

However, the style was not always embraced by the critical establishment. Some critics dismissed trompe l'oeil as mere technical trickery, lacking the intellectual depth or moral uplift associated with historical painting or the sublime grandeur of landscape painting, then dominated by figures like Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt of the Hudson River School. For Peto and his peers, trompe l'oeil was a serious artistic pursuit, a way to explore perception, representation, and the nature of reality itself.

Rediscovery and Reappraisal

For decades after his death in New York City in 1907 (while seeking treatment for Bright's disease), John F. Peto remained a largely forgotten figure, his work often misattributed to the more famous Harnett. The turning point came in the mid-20th century, largely thanks to the meticulous research of art historian Alfred Frankenstein.

In the 1940s, Frankenstein embarked on a study of William Michael Harnett. Through careful stylistic analysis, examination of signatures (detecting forgeries), and tracking down provenance, he began to distinguish a separate, distinct artistic personality whose works had been subsumed under Harnett's name. This artist was John F. Peto. Frankenstein's groundbreaking work, culminating in the 1949 article "Harnett, True and False" and later exhibitions and publications, effectively resurrected Peto's reputation.

The first major solo exhibition of Peto's work, organized by Frankenstein, was held at the Brooklyn Museum in 1950. This event, along with subsequent scholarship and exhibitions, firmly established Peto as a major figure in his own right. Museums began acquiring his work, and his paintings started appearing in surveys of American art. His style, once seen perhaps as a softer version of Harnett's, came to be appreciated for its unique qualities: its painterly texture, its atmospheric light, and its poignant emotional depth.

Peto's Enduring Place in American Art

Today, John Frederick Peto is recognized as one of the foremost American still-life painters of the late 19th century. He stands alongside Harnett and Haberle as a master of trompe l'oeil, but his contribution extends beyond technical illusionism. His work offers a unique blend of realism and poetic sensibility, transforming humble, everyday objects into subjects of quiet contemplation.

Compared to the earlier generation of American still-life painters like Raphaelle Peale, whose arrangements often possess a classical clarity and order, Peto's work feels more intimate, informal, and imbued with a sense of personal history. His focus on the worn, the used, and the discarded provides a counterpoint to the Gilded Age's emphasis on progress and prosperity, offering instead a meditation on time, decay, and the enduring presence of the past.

His influence can be seen less directly than Harnett's, perhaps, but his exploration of everyday objects and the nature of representation resonates with later developments in American art. Artists associated with Pop Art, or conceptual artists like Jasper Johns who explored the relationship between object and image, arguably share a distant lineage with Peto's intense focus on the commonplace and the act of depiction itself.

Conclusion

John Frederick Peto's artistic journey is one of quiet dedication, subtle innovation, and eventual recognition. A master technician within the demanding trompe l'oeil tradition, he infused his work with a distinctive warmth, texture, and emotional resonance. His paintings of well-thumbed books, silent instruments, and cluttered office boards transcend mere illusionism, becoming poignant reflections on the passage of time, the beauty of imperfection, and the stories embedded in the objects of everyday life. Rescued from obscurity by dedicated scholarship, Peto now holds a secure and significant place in the canon of American art, celebrated for his unique vision and his sensitive portrayal of a world marked by use, memory, and quiet dignity.