Giovanni Battista di Jacopo, known to the art world as Rosso Fiorentino, or "the Red Florentine" due to his distinctive red hair, stands as one of the most original and influential painters of the Italian High Renaissance and a pivotal figure in the development of Early Mannerism. Born in Florence on March 8, 1494, his career, though tragically cut short in 1540, left an indelible mark on the trajectory of European art. His work is characterized by its departure from the harmonious classicism of his predecessors, embracing instead a style noted for its expressive intensity, unconventional compositions, vibrant and often unsettling color palettes, and elongated, dynamic figures.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Rosso Fiorentino's artistic journey began in the vibrant artistic crucible of early 16th-century Florence. At this time, the city was still basking in the afterglow of giants like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, though the latter two were increasingly active in Rome. The prevailing artistic climate was one of immense innovation, but also one where younger artists sought new modes of expression beyond the established ideals of High Renaissance harmony and naturalism.

It is widely accepted that Rosso's primary training occurred in the workshop of Andrea del Sarto, one of Florence's leading painters. Del Sarto, known as "the faultless painter" for his technical mastery and graceful compositions, provided a strong foundation. However, Rosso, like his contemporary and fellow Sarto pupil Jacopo Pontormo, was not content to merely emulate his master. Instead, both artists absorbed the lessons of the High Renaissance but pushed them in new, more personal and emotionally charged directions.

The relationship between Rosso and Pontormo is particularly significant. They are often considered the twin pillars of early Florentine Mannerism. While their styles differed—Pontormo's often more introspective and ethereal, Rosso's more agitated and forceful—they shared a common desire to break free from classical restraint. They experimented with distorted perspectives, elongated human forms, and subjective color choices that prioritized emotional impact over strict naturalism. Their early works already hinted at this departure, challenging the serene and balanced compositions favored by artists like Fra Bartolommeo, another influential Florentine painter of the period.

The Emergence of a Distinctive Mannerist Style

Mannerism, the style Rosso Fiorentino helped to pioneer, emerged in the 1520s as a reaction against the idealized naturalism and harmonious compositions of the High Renaissance. It was a style born of a period of social, religious, and political upheaval in Italy, including the Sack of Rome in 1527, which profoundly affected the psyche of artists and patrons alike. Mannerist artists often favored complexity, artifice, and emotional intensity.

Rosso's style is a quintessential example of this shift. His figures are often contorted into elegant but unnatural poses, their limbs elongated and their musculature sometimes exaggerated. His compositions can be crowded and unsettling, rejecting the clear, rational spatial arrangements of artists like Raphael. Color, in Rosso's hands, became a tool for expressive effect rather than realistic depiction; he employed jarring juxtapositions and acidic hues that could create a sense of unease or heightened drama. This was a conscious move away from the sfumato of Leonardo or the balanced palettes of the High Renaissance.

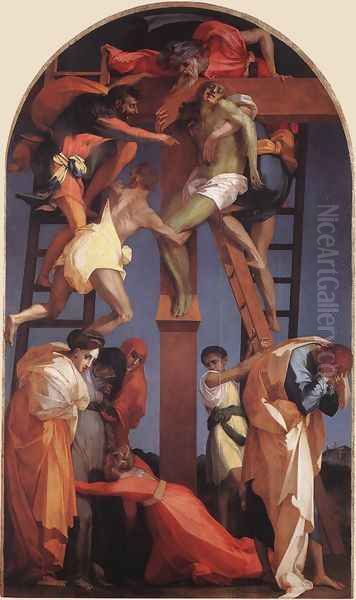

His early works in Florence, such as the Assumption of the Virgin (1517) in the Santissima Annunziata, already displayed these tendencies. However, it was with works like the Deposition from the Cross (1521) for the Duomo in Volterra that his mature Mannerist style truly crystallized. This painting, with its stark, angular figures, their faces etched with profound grief, and its dramatic, almost abstract background, is a powerful expression of spiritual anguish that transcends traditional representations of the theme.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Rosso Fiorentino's oeuvre, though not vast due to his relatively short life, contains several masterpieces that exemplify his unique artistic vision.

The _Deposition from the Cross_ (1521, Pinacoteca Comunale, Volterra) is arguably his most famous early work. It is a radical departure from earlier, more serene depictions of this subject by artists like Fra Angelico or Perugino. Rosso's figures are emaciated and angular, their grief palpable and almost grotesque. The sky is a stark, geometric abstraction, and the colors are sharp and dissonant. The elongated body of Christ, awkwardly supported, and the frantic gestures of the surrounding figures create a scene of intense emotional turmoil and spiritual desolation.

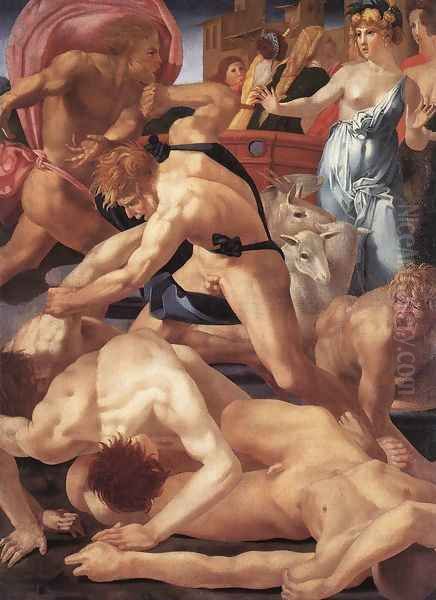

Another key work is _Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro_ (circa 1523, Uffizi Gallery, Florence). This painting is a whirlwind of dynamic, muscular figures engaged in violent action. The composition is dense and complex, with bodies contorted and overlapping. Rosso's fascination with the nude male form, clearly influenced by Michelangelo's work on the Sistine Chapel ceiling and his sculptures, is evident here, but pushed towards a more frenetic and less idealized representation. The raw energy and almost brutal power of the scene are characteristic of Rosso's dramatic intensity.

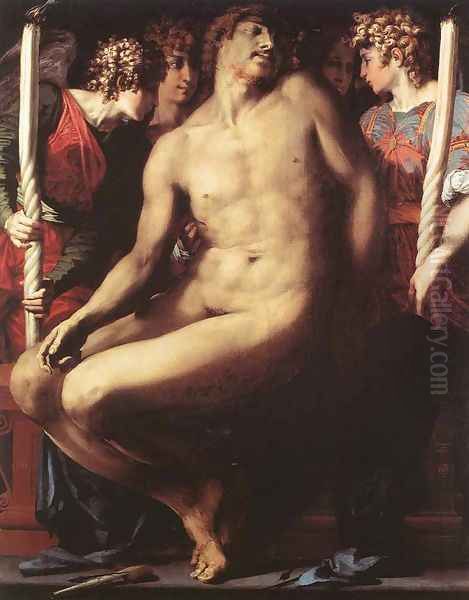

The _Dead Christ with Angels_ (circa 1524-1527, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) is a deeply moving and somewhat unsettling work. Christ's body, pale and elongated, is supported by grieving angels. The anatomical rendering is precise yet stylized, emphasizing the suffering and pathos of the moment. The painting showcases Rosso's ability to convey profound religious feeling through his distinctive Mannerist vocabulary, including the use of strong chiaroscuro and emotionally resonant colors.

His _Pala Dei_ (1522, Palazzo Pitti, Florence), depicting the Madonna and Child with saints, also demonstrates his evolving style, with elongated figures and a heightened sense of psychological tension among the sacred personages. Even in more traditional altarpiece formats, Rosso infused his work with a unique dynamism and emotional charge.

Travels and Artistic Development: Rome, Venice, and Beyond

Like many artists of his generation, Rosso Fiorentino sought opportunities beyond Florence. Around 1524, he traveled to Rome, a city then at the zenith of its artistic splendor under papal patronage. In Rome, he would have encountered the works of Raphael (who had died in 1520 but whose workshop, led by figures like Giulio Romano, continued his legacy) and the towering presence of Michelangelo. Rosso's Roman period saw him absorb these influences, particularly the monumentality of Michelangelo, yet he retained his distinctive stylistic traits. It's plausible he met Giulio Romano before Romano's departure for Mantua.

The devastating Sack of Rome in 1527 by the troops of Emperor Charles V marked a turning point for many artists, scattering them across Italy and beyond. Rosso himself was reportedly captured and mistreated during the Sack. Following this traumatic event, he worked in various Italian cities, including Perugia, Borgo San Sepolcro (where he painted The Lamentation over the Dead Christ), Arezzo, and Venice.

His time in Venice, though perhaps not prolonged, brought him into contact with the rich coloristic traditions of Venetian painting, dominated by artists like Titian and, emerging at the time, Tintoretto. In Venice, Rosso also formed a friendship with the influential writer and satirist Pietro Aretino, a prominent figure in the artistic and literary circles of the time. Aretino's own provocative and unconventional nature may have resonated with Rosso's artistic temperament.

The Call to France: The School of Fontainebleau

The most significant move in Rosso Fiorentino's later career came in 1530 when he was invited to France by King Francis I. Francis I was a great patron of the arts, keen to bring the sophistication of the Italian Renaissance to the French court. Rosso was tasked with overseeing the decoration of the Palace of Fontainebleau, one of the king's most ambitious projects.

At Fontainebleau, Rosso, appointed as "first painter to the king," was given considerable artistic freedom and resources. He was responsible for designing and executing vast decorative schemes, primarily in the Galerie François I. Here, he created a complex interplay of frescoes, elaborate stucco work, and wood paneling, establishing a new and influential decorative style. His collaborator in these endeavors, from 1532, was another Italian artist, Francesco Primaticcio, who had studied with Giulio Romano. Together, Rosso and Primaticcio became the leading figures of what is known as the First School of Fontainebleau.

The style they developed at Fontainebleau was a sophisticated and often eroticized form of Mannerism, blending mythological and allegorical subjects with intricate ornamentation. Rosso's designs featured elongated, elegant figures in complex poses, often framed by elaborate stucco cartouches and strapwork—a decorative motif that became a hallmark of the Fontainebleau style. Artists like Benvenuto Cellini, the famed sculptor and goldsmith, also worked for Francis I during this period, contributing to the rich artistic environment. The influence of Michelangelo remained apparent in Rosso's treatment of the human form, but it was adapted to a more courtly and decorative aesthetic.

The School of Fontainebleau was immensely influential, not only in France but also in disseminating Mannerist aesthetics throughout Northern Europe. Artists such as Niccolò dell'Abate would later join Primaticcio in continuing the work at Fontainebleau after Rosso's death, further solidifying its impact.

Controversies, Personal Life, and Tragic End

Rosso Fiorentino's life was not without its share of turmoil and controversy, reflecting the often-intense and competitive nature of the art world and his own passionate temperament. His artistic style itself was a departure from convention and could be seen as provocative. His nudes, while demonstrating anatomical knowledge, were sometimes considered overly stylized or their emotional expressions too extreme for conservative tastes. For instance, one of his drawings depicting a young man with what some scholars interpret as a skin ailment has been seen as a symbolic representation rather than a purely clinical one, sparking debate about its meaning.

The most tragic episode in Rosso's life, according to Giorgio Vasari (the 16th-century artist and biographer, whose accounts, while invaluable, sometimes contain embellishments), concerned an accusation of theft. Vasari recounts that Rosso was falsely accused by a friend and fellow painter, Francesco di Pellegrino. Although Rosso was eventually cleared of the charges, the public scandal and the perceived betrayal deeply affected him. Overwhelmed by shame and anger, Vasari claims Rosso took his own life by poison in Paris on November 14, 1540, at the age of 46. While the exact circumstances of his death are debated by modern scholars, it marked a premature end to a brilliant and innovative career.

His relationships with contemporaries like Pontormo were complex; they were artistic compatriots in forging Mannerism, yet their individual paths and stylistic nuances led to inevitable comparisons and perhaps even rivalries, common among artists of the era.

Rosso's Enduring Legacy and Influence

Despite his relatively short career, Rosso Fiorentino's impact on the course of art was profound. He was a key instigator of the Mannerist style in Florence and played a crucial role in its transmission to France, where it blossomed into the influential School of Fontainebleau. His work challenged the established norms of the High Renaissance, paving the way for a more subjective, expressive, and psychologically complex approach to art.

His influence can be seen in the work of his direct collaborators like Primaticcio and in the broader development of French art. The decorative style he pioneered at Fontainebleau, with its combination of painting and stucco, had a lasting impact on interior design and ornamentation in Northern Europe.

Beyond his immediate circle, echoes of Rosso's intensity, his dramatic use of color and light, and his expressive figural distortions can be found in later artists. While a direct line of influence is complex to trace, the emotional power and anti-classical tendencies of Mannerism, which Rosso championed, resonated with later artists who sought to break from academic conventions. For example, the dramatic intensity and emotional realism found in the works of Caravaggio, though stylistically different, share a certain spiritual kinship with the expressive force of Rosso's art. Even artists like El Greco, who developed his unique style in Spain, worked within a Mannerist framework that valued elongated forms and spiritual intensity. The expressive, sometimes caricatural line in the work of later artists like the British satirist Thomas Rowlandson might also find distant antecedents in the graphic freedom seen in some of Rosso's drawings and prints.

His innovative approach to printmaking, particularly his etchings, also contributed to his legacy, showcasing a more humorous and sometimes grotesque side to his artistic personality.

Where to See His Works Today

Rosso Fiorentino's paintings and drawings are housed in major museums and collections around the world. Key institutions include:

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence: Home to Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro and the Spedalingo Altarpiece (Madonna and Child with Four Saints) (1518).

Palazzo Pitti, Florence: Holds the Pala Dei (Madonna and Child with Ten Saints) (1522).

Pinacoteca Comunale, Volterra: Features the iconic Deposition from the Cross (1521).

Musée du Louvre, Paris: Contains works such as The Challenge of the Pierides and Pietà. It is also the primary repository of the decorative legacy of Fontainebleau.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Houses the poignant Dead Christ with Angels.

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore: Possesses a version of The Holy Family with the Young Saint John the Baptist.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Holds drawings by Rosso, offering insight into his creative process.

Churches in Italy: Some works remain in or near their original locations, such as in Borgo San Sepolcro and Città di Castello. The Diocesan Museum of Volterra also holds important works.

His frescoes and stucco work in the Galerie François I at the Palace of Fontainebleau remain his most extensive and site-specific creations, offering a unique immersion into his decorative vision.

Conclusion

Rosso Fiorentino was an artist of restless innovation and profound emotional depth. A leading light of Early Mannerism, he dared to deviate from the serene classicism of the High Renaissance, forging a style that was personal, expressive, and often unsettling. From his formative years in Florence alongside Pontormo, through his experiences in Rome and other Italian centers, to his crowning achievements at the court of Francis I in Fontainebleau, Rosso consistently pushed artistic boundaries. His legacy lies not only in his striking paintings and influential decorative schemes but also in his role as a catalyst for change, shaping the artistic landscape of 16th-century Europe and leaving an indelible mark that continues to fascinate and inspire. His art remains a testament to a turbulent era and a uniquely powerful creative spirit.