Edward Adrian Wilson stands as a singular figure in the annals of exploration, a man whose profound contributions to science were matched by an equally remarkable artistic talent. A physician, naturalist, and gifted painter, Wilson's life was inextricably linked with the heroic age of Antarctic exploration, culminating in his tragic death alongside Captain Robert Falcon Scott on their return from the South Pole. His legacy, however, endures not only in the scientific data he meticulously collected but also in the evocative and scientifically accurate artworks that provide a unique window into the stark beauty and unforgiving nature of the Earth's southernmost continent. This article delves into the life, work, and artistic significance of Edward Adrian Wilson, a man who wielded both the scalpel and the paintbrush with extraordinary skill and dedication.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born on July 23, 1872, in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, Edward Adrian Wilson, affectionately known as "Uncle Bill," was the second son and fifth child of Dr. Edward Thomas Wilson and Mary Agnes, née Whishaw. His father was a respected physician with a keen interest in natural history and science, while his mother, a poultry farmer, instilled in him a love for the countryside and its creatures. This upbringing in a relatively affluent and intellectually stimulating environment fostered Wilson's early passions. He was a sensitive and observant child, drawn to the natural world from a young age, spending countless hours sketching the flora and fauna around his home.

His formal education began at Cheltenham College, where he excelled. He later proceeded to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, in 1891, to study Natural Sciences. It was at Cambridge that his scientific acumen began to truly flourish, alongside a deepening commitment to his Christian faith, which would become a guiding principle throughout his life. He was known for his gentle demeanor, unwavering integrity, and a quiet determination. Even during his university years, his artistic talents were evident, as he filled notebooks with detailed sketches of biological specimens and landscapes. He was not formally trained as an artist in an academic sense, but rather developed his skills through meticulous observation and practice, much like the self-taught naturalists of previous generations, such as John James Audubon, whose dedication to capturing American birdlife set a high bar for natural history illustration.

After Cambridge, Wilson pursued medical training at St George's Hospital, London, qualifying as a physician (MB) in 1900 and Bachelor of Surgery (BCh) in 1901. During this period, he contracted pulmonary tuberculosis, a serious illness that necessitated a period of convalescence in Norway and Switzerland. This interruption, though challenging, perhaps further honed his appreciation for stark, beautiful landscapes and the resilience of life, themes that would later dominate his Antarctic work. It was also during his recovery that he further developed his skills as a watercolorist, capturing the alpine scenery with the same precision he applied to biological subjects.

The Call of the Ice: The Discovery Expedition

In 1901, a pivotal opportunity arose. Robert Falcon Scott was organizing the British National Antarctic Expedition (1901-1904), more famously known as the Discovery Expedition. Wilson, despite his recent illness, applied and was selected as junior surgeon, zoologist, and expedition artist. This appointment marked the true beginning of his Antarctic career and provided the canvas for his most enduring work. His medical background was crucial, but his skills as a naturalist and artist were equally valued for documenting the then largely unknown continent.

Aboard the Discovery, Wilson quickly proved his mettle. He was responsible for collecting and preparing vertebrate specimens, particularly birds and seals. His meticulous notes and detailed sketches were invaluable. As an artist, he faced unprecedented challenges: painting in sub-zero temperatures where watercolors would freeze, and capturing the subtle, often monochromatic hues of the Antarctic landscape. He developed techniques to overcome these obstacles, sometimes mixing his paints with glycerine or working rapidly in sheltered spots. His resulting artworks were not mere impressions but careful, scientific records imbued with an artist's sensitivity. He depicted the majestic ice formations, the ethereal auroras, and the unique wildlife, from the smallest petrels to the lumbering seals.

During the Discovery Expedition, Wilson participated in several arduous sledging journeys. Most notably, he, Scott, and Ernest Shackleton undertook a southern journey in 1902-1903, attempting to reach the South Pole. They reached a then-Farthest South of 82°17'S, but the journey was fraught with hardship, including the onset of scurvy. Wilson's medical skills, resilience, and unwavering good spirits were crucial to the party's survival. His sketches from this period, though often made under duress, are poignant records of their struggle and the alien beauty of the landscapes they traversed. His ability to capture the subtle play of light on snow and ice, and the vastness of the Antarctic wilderness, set his work apart. One might see a parallel in the dedication of earlier maritime artists like William Hodges, who accompanied Captain Cook and faced his own challenges in depicting unfamiliar lands and atmospheric conditions.

Wilson's scientific contributions from this expedition were significant. He made detailed studies of penguin embryology, particularly of the Emperor Penguin, believing their development might hold clues to avian evolution. His observations on Antarctic birds and seals were published in the expedition's scientific reports, often accompanied by his own illustrations. These illustrations bear comparison with the work of other great scientific illustrators of the 19th and early 20th centuries, such as Joseph Wolf, known for his lifelike and dynamic animal portraits, or John Gould, whose lavishly illustrated ornithological works were landmarks of the era.

Interlude: Scientific Work and Artistic Development

Upon returning to England in 1904, Wilson was celebrated for his contributions. He set about working on the zoological results of the Discovery Expedition. He also undertook work for the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries, investigating grouse disease in Scotland. This period saw him continue to refine his artistic skills. He contributed illustrations to several books, most notably A History of British Mammals (1910-1921) by Gerald E.H. Barrett-Hamilton, for which he provided numerous plates. His work here demonstrated his versatility, moving from the exotic Antarctic fauna to the familiar wildlife of Britain. His style remained consistent: a commitment to accuracy, a delicate touch with watercolors, and an ability to convey the character of his subjects.

His reputation as both a scientist and an artist grew. He was a man of deep faith and quiet conviction, respected for his integrity and gentle nature. He married Oriana Fanny Souper in 1901, just before departing on the Discovery, and their correspondence reveals a deep and supportive partnership. Wilson was not an artist who sought the limelight of the London art scene; his art was intrinsically linked to his scientific pursuits and his profound connection with the natural world. He was, in this sense, part of a tradition of artist-naturalists that included figures like Archibald Thorburn, a contemporary renowned for his stunning watercolor paintings of British birds, whose work Wilson would have known and likely admired for its precision and beauty.

The allure of the Antarctic, however, remained strong. When Scott began planning his second expedition, the British Antarctic Expedition (1910-1913), or Terra Nova Expedition, with the explicit goal of being the first to reach the South Pole, he turned to Wilson as his chief of scientific staff and confidant. Wilson, despite the inherent dangers and the memory of past hardships, did not hesitate.

The Terra Nova Expedition: Science, Art, and Tragedy

The Terra Nova Expedition, which departed in 1910, was even more ambitious scientifically than its predecessor. Wilson, as chief scientist, oversaw a wide-ranging program of research, encompassing geology, meteorology, magnetism, and biology. He was also personally driven by a specific scientific quest: to collect the eggs of the Emperor Penguin from their winter breeding colony at Cape Crozier. It was believed that the Emperor Penguin was a primitive form of bird, and that its embryos might reveal an evolutionary link between reptiles and birds. This was a theory that, while later disproven in its specifics, fueled one of an extraordinary and perilous undertakings of the expedition.

The Winter Journey

In the austral winter of 1911 (June-August), Wilson led a small party, consisting of himself, Lieutenant Henry "Birdie" Bowers, and Apsley Cherry-Garrard, on the "Winter Journey" to Cape Crozier. This journey, undertaken in almost complete darkness and unimaginable cold (temperatures plummeted to -60°C, and even lower), is one of the most harrowing and heroic tales in polar exploration. Their objective was to collect those precious Emperor Penguin eggs. Cherry-Garrard later immortalized this ordeal in his book, The Worst Journey in the World.

Despite frostbite, near-starvation, and their tent being blown away in a blizzard, they reached the penguin colony and managed to secure three eggs (though two were cracked). Wilson, throughout this unimaginable trial, continued to sketch and make observations, his dedication to science and art unwavering. His sketches from this period, such as "Paraselenæ, June 23rd 1911," depicting a lunar halo phenomenon, are remarkable not only for their scientific value but as testaments to human endurance and the pursuit of knowledge in the face of extreme adversity. The conditions were so severe that their teeth cracked in the cold, and any exposed skin was instantly frostbitten. Wilson’s ability to produce any artwork at all under such conditions is astounding.

The Journey to the Pole and Tragic End

Following the Winter Journey, preparations began for the main event: the trek to the South Pole. Wilson was chosen by Scott as one of the final five-man party to make the push for the Pole. The others were Captain Scott himself, Lieutenant Bowers, Captain Lawrence Oates, and Petty Officer Edgar Evans. They set out in late 1911.

The journey south was an epic of endurance. Wilson, as always, maintained his scientific observations and sketching whenever possible, documenting geological formations and atmospheric phenomena. His diaries and sketches provide invaluable insights into the challenges they faced. They reached the South Pole on January 17, 1912, only to find that Roald Amundsen's Norwegian expedition had beaten them by over a month. The disappointment was profound.

The return journey was a descent into tragedy. Weakened by insufficient rations, extreme cold, and debilitating frostbite, the party struggled. Edgar Evans was the first to die, near the foot of the Beardmore Glacier. Later, Captain Oates, suffering severely from frostbite and recognizing he was slowing the others, famously walked out of the tent into a blizzard, saying, "I am just going outside and may be some time." His sacrifice was in vain.

Scott, Wilson, and Bowers pushed on, but were eventually trapped by a relentless blizzard only 11 miles from One Ton Depot, a major supply cache. It was here, in their tent, that they met their end in late March 1912. Wilson, ever the scientist and artist, continued to write his diary and make observations until he was too weak to continue. His final letters were full of courage and concern for others. When a search party found their tent eight months later, they discovered the bodies, along with their diaries, scientific specimens (including the precious Emperor Penguin eggs and 35 pounds of Glossopteris fossils from the Beardmore Glacier, crucial evidence for the theory of continental drift), and Wilson's sketches.

Wilson the Artist: Style, Subjects, and Significance

Edward Wilson's art is characterized by its meticulous accuracy, delicate use of watercolor, and a profound sensitivity to the nuances of the Antarctic environment. He was not a flamboyant stylist, nor did he seek to romanticize or dramatize his subjects in the manner of some contemporary adventure illustrators. His primary aim was often scientific record, yet his work transcends mere documentation.

Style and Techniques

Wilson predominantly worked in watercolor and pencil. His watercolors are notable for their subtle gradations of color, capturing the ethereal blues, greys, and whites of the ice and sky, often punctuated by the vibrant hues of a polar sunset or the aurora australis. He had an exceptional eye for detail, whether depicting the feather patterns of a penguin or the geological strata of a cliff face. His pencil sketches, often made rapidly in the field, are equally impressive for their precision and economy of line.

Painting in the Antarctic presented unique challenges. Freezing temperatures meant that water-based paints would solidify. Wilson experimented with various techniques, including adding glycerine to his water, and working quickly in sheltered, slightly warmer conditions, such as inside a tent or a pre-fabricated hut. His ability to produce such refined work under these conditions speaks volumes about his skill and determination. His approach was akin to that of a field naturalist, where observation and rapid, accurate recording are paramount. One could draw parallels to the field sketches of Thomas Baines, who documented his African and Australian expeditions with remarkable detail and immediacy, or even the earlier work of Sydney Parkinson, artist on Captain Cook's first voyage, who faced similar challenges of depicting new worlds under difficult conditions.

Key Subjects and Representative Works

Wilson's subjects were diverse, reflecting his broad interests as a naturalist and his experiences as an explorer.

His depictions of Antarctic wildlife, particularly birds, are among his most celebrated works. He painted numerous species of penguins (Emperor, Adélie, King), petrels, skuas, and albatrosses. These are not static portraits but often show the birds in their natural habitat, engaged in characteristic behaviors. His illustrations for Nature Notebooks and his contributions to the scientific reports of the expeditions are prime examples.

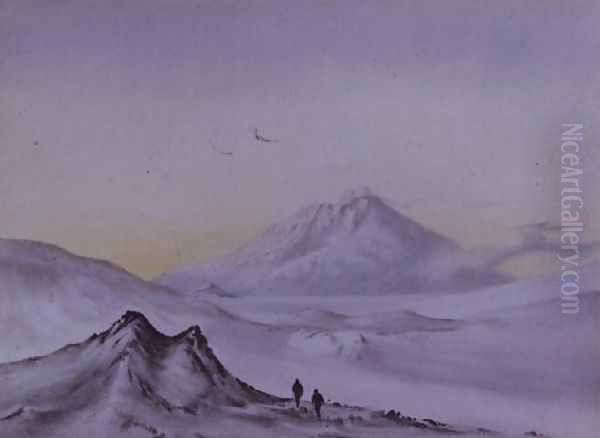

His landscapes capture the grandeur, desolation, and subtle beauty of the Antarctic. Works like "Mount Erebus from the North West" (1911) or "Sunset, Cape Evans" (1911) showcase his ability to render the dramatic volcanic peak and the fleeting colors of the polar sky. He was particularly adept at depicting ice formations – glaciers, icebergs, pressure ridges – with a geologist's understanding and an artist's eye. His sketch "Paraselenæ, January 15, 1911" (different from the June one) is a fine example of his recording of atmospheric optical phenomena.

The human element, though less frequent, is also present. Sketches of expedition life, the Discovery or Terra Nova beset in ice, or the distant figures of sledgers against a vast icy plain, convey the scale of human endeavor in this extreme environment. These works resonate with the spirit of expeditionary art, where the artist is both participant and observer. The photographer Herbert Ponting, who was the official photographer on the Terra Nova Expedition, created iconic images of the expedition, and his work provides a fascinating counterpoint to Wilson's paintings and sketches. While Ponting captured moments with the immediacy of the camera, Wilson offered a more interpretive, hand-rendered vision, often imbued with a quiet lyricism.

The Purpose of His Art

For Wilson, art and science were not separate endeavors but complementary ways of understanding and engaging with the world. He once wrote, "The sketching, of course, is a delight, and I am sure it is a great help to accurate observation. One sees so much more by drawing a thing than by merely looking at it." His art was a tool for scientific inquiry, a means of recording data, and a way of communicating his observations.

However, it was also more than that. His paintings convey a deep reverence for nature and a sense of wonder. He saw beauty even in the harshest environments. There is a spiritual quality to much of his work, reflecting his profound Christian faith. He did not generally sell his original artworks, viewing them as part of his personal and scientific record. This reluctance to commercialize his art aligns him with a certain type of artist-scientist who values the process and the knowledge gained above public acclaim or financial reward, perhaps akin to the ethos of someone like Beatrix Potter, who combined acute natural observation in her art with a successful literary career, though her subject matter was vastly different.

Wilson's dedication to truth in his art, his meticulous rendering of detail, and his ability to convey the atmosphere of the Antarctic place him in a unique position. While perhaps not as widely known in mainstream art history circles as, for example, landscape painters like J.M.W. Turner, who captured the sublime power of nature, or Frederic Edwin Church, whose grand canvases depicted exotic locales including the Arctic, Wilson's contribution is significant within the intersecting fields of scientific illustration, expeditionary art, and British watercolor painting. His work offers a unique and invaluable visual record of a pivotal era in exploration.

Legacy and Remembrance

The discovery of Scott's, Wilson's, and Bowers' bodies, along with their records and Wilson's artworks, sent shockwaves through Britain and the world. Their story became one of heroic failure, of courage and sacrifice in the pursuit of scientific knowledge and national prestige. Wilson, in particular, was lauded for his scientific contributions, his artistic talent, and his unwavering moral character. Apsley Cherry-Garrard described him as "the finest character I ever met."

Wilson's scientific legacy is substantial. The Emperor Penguin eggs he collected, at such terrible cost, were delivered to the Natural History Museum in London and contributed to the understanding of avian embryology. His geological samples, particularly the Glossopteris fossils, provided key evidence for the then-emerging theory of continental drift, showing that Antarctica was once part of a warmer supercontinent, Gondwana. His detailed zoological and ornithological notes and illustrations remain valuable resources.

His artistic legacy is equally enduring. His paintings and sketches are held in several collections, notably the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, the Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum (The Wilson), and the Royal Geographical Society. They continue to be admired for their beauty, accuracy, and historical significance. They provide a visual narrative of the expeditions that complements the written accounts and photographs, offering a personal and often poignant perspective. His work has influenced subsequent generations of wildlife artists and those who seek to depict extreme environments. One might consider contemporary wildlife artists like Robert Bateman, whose detailed realism and commitment to conservation echo Wilson's dedication to capturing nature accurately, albeit with modern techniques and a different global context.

Statues and memorials to Wilson and his companions were erected throughout Britain and the Commonwealth. The Wilson, Cheltenham's art gallery and museum, is named in his honor and houses a significant collection of his work and personal effects. His story, and that of the Terra Nova Expedition, continues to inspire books, documentaries, and artistic interpretations, a testament to the enduring power of their endeavor.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Edward Adrian Wilson was a man of many talents and profound integrity. As a physician, he cared for his companions; as a scientist, he meticulously observed and recorded the natural world; and as an artist, he captured its essence with skill and sensitivity. His life was one of service, dedication, and an unwavering pursuit of knowledge, even in the face of unimaginable hardship.

His artworks are more than just illustrations; they are a visual diary of discovery, a testament to the beauty and terror of the Antarctic, and a reflection of the remarkable spirit of the man who created them. In the brushstrokes of his watercolors and the lines of his sketches, we see not only the icy landscapes and unique fauna of a distant continent but also the keen eye, steady hand, and compassionate heart of Edward Wilson. He remains an inspirational figure, a reminder that the pursuit of science and the creation of art can be deeply intertwined, and that true greatness often lies in quiet dedication and selfless courage. His contributions to both art and science ensure that his vision of the Antarctic, and his example of a life lived with purpose, will endure.