Lucie Cousturier (1876–1925) stands as a significant, though for a long time overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century French art. More than just a painter, she was a perceptive writer, a dedicated art theorist, an educator, and a passionate anti-colonial activist. Her life and work offer a fascinating window into the vibrant artistic currents of her time, particularly Neo-Impressionism, and her multifaceted contributions are increasingly recognized for their depth and foresight. This exploration delves into her artistic journey, her intellectual pursuits, and her unwavering commitment to social justice, painting a portrait of a woman who wielded both the brush and the pen with remarkable conviction.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Paris in 1876 (some sources state 1870, but 1876 is more commonly cited by recent scholarship), Lucie Cousturier entered a world brimming with cultural and industrial innovation. Her family background was itself touched by ingenuity; her parents were pioneers in the manufacture of rubber dolls, suggesting an environment that valued creativity and new methods. This upbringing may have fostered the independent spirit and intellectual curiosity that would later define her career.

Cousturier's artistic inclinations emerged early. By the age of fourteen, she had begun her formal training in painting. Crucially, she sought out and studied under two of the leading figures of the Neo-Impressionist movement: Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross. This decision was pivotal, placing her directly at the heart of one of the most avant-garde artistic developments of the era. Learning from these masters provided her with a rigorous grounding in the theories and techniques of Pointillism, shaping her artistic vision and technical approach from a formative stage. Her association with these artists was not merely that of a student; she became an integral part of their circle, absorbing their ideas and contributing to their discourse.

The Embrace of Neo-Impressionism

Neo-Impressionism, the artistic current that Cousturier so wholeheartedly embraced, emerged in the mid-1880s as a scientific and methodical response to the more intuitive approach of Impressionism. Spearheaded by Georges Seurat, with Paul Signac as its most ardent advocate and theorist after Seurat's early death, the movement was founded on principles of optics and color theory. Artists like Seurat, Signac, and their followers, including Camille Pissarro for a period, sought to create more luminous and vibrant paintings by applying small, distinct dots or dabs of pure color to the canvas.

This technique, known variously as Pointillism (referring to the dots of paint) or Divisionism (referring to the division of colors), relied on the concept of optical mixing. Instead of mixing colors on the palette, Neo-Impressionists placed complementary colors side-by-side on the canvas, believing that the viewer's eye would blend them, resulting in a more brilliant and intense visual experience than could be achieved with traditional mixing. The aim was to achieve a harmonious and scientifically ordered representation of light and color, moving beyond the fleeting impressions captured by artists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Cousturier became a devoted practitioner of this demanding technique.

Cousturier's Artistic Style and Themes

Lucie Cousturier’s body of work clearly demonstrates her mastery of Neo-Impressionist principles. She favored landscapes, outdoor scenes, and intimate domestic interiors, often imbued with the radiant light of Southern France, a region beloved by many Neo-Impressionists, including her mentors Signac and Cross. Her canvases are characterized by a meticulous application of color, creating a shimmering, mosaic-like surface that captures the vibrancy of her subjects.

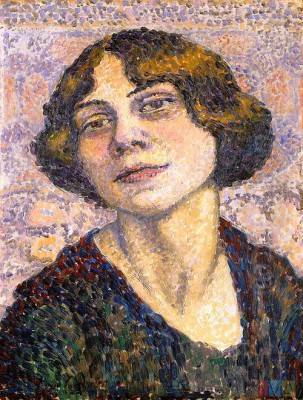

One of her most celebrated works, Femme faisant du crochet (Woman Crocheting), painted around 1908 and now housed in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, exemplifies her style. The painting depicts her niece, Geneviève Bosq, engrossed in her needlework within a sunlit interior. The scene is rendered with a delicate interplay of colored dots, conveying not only the physical forms but also the atmosphere and the quality of light filtering into the room. The careful construction and harmonious color palette are hallmarks of her dedication to the Neo-Impressionist aesthetic. Other works, such as her Self-Portrait (c. 1905-1910), reveal a thoughtful and introspective artist, confident in her chosen artistic language. Her paintings often exude a sense of tranquility and order, reflecting the Neo-Impressionist pursuit of harmony.

A Scholarly Voice: Documenting Neo-Impressionism

Beyond her own artistic practice, Lucie Cousturier played a crucial role as a writer and theorist of Neo-Impressionism. Beginning around 1911, she started publishing articles and monographs on the movement's key figures, including Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, Ker-Xavier Roussel, Paul Cézanne, and Maurice Denis. Her writings were not mere appreciations; they were insightful analyses grounded in a deep understanding of the artists' intentions and techniques.

She became a recognized expert in the field, and her texts helped to articulate and disseminate the principles of Neo-Impressionism to a wider audience. Her close personal and professional relationships with artists like Signac and Cross gave her unique access and insights, making her chronicles particularly valuable. She understood, for instance, Seurat's ambition, writing eloquently of how he "placed his canvas before the sky, to color his colors, while he carried on a constant dialogue with space." Her contributions as an art historian and critic cemented her intellectual standing within the Parisian art world and helped to shape the historical understanding of the movement.

Art as Activism: Challenging Colonial Norms

Lucie Cousturier's engagement with the world extended far beyond the confines of the studio and the art gallery. The outbreak of World War I brought a new dimension to her life and work. During the war, she found herself near Fréjus in the South of France, where a large contingent of Senegalese Tirailleurs (colonial infantry) was stationed. Moved by their situation and a profound sense of justice, Cousturier volunteered to teach these soldiers French.

This experience was transformative. It brought her into direct contact with individuals from France's colonial empire and exposed her to the realities of colonialism. Her interactions with the Senegalese soldiers formed the basis of her powerful and poignant book, Des Inconnus chez moi (Strangers in My Home), published in 1920. This work, a blend of memoir and social critique, offered a humane and critical perspective on the colonial subjects who were fighting for France, challenging prevailing racist and colonialist attitudes. It was a courageous stance at a time when such views were far from mainstream. Her writings from this period mark her emergence as a significant anti-colonial voice, advocating for the dignity and rights of colonized peoples.

Voyage to West Africa: An Artist's Perspective

Cousturier's commitment to understanding and challenging colonialism led her to embark on a significant journey. In 1921, she traveled to French West Africa, spending approximately ten months there. This was not a typical colonial tourist's trip; Cousturier went with the intention of observing, learning, and documenting. She sought to understand the cultures she encountered on their own terms and to witness firsthand the impact of French colonial rule.

Her experiences in West Africa further fueled her anti-colonial convictions and provided rich material for her art and writing. She produced numerous sketches, watercolors, and paintings during and after her trip, capturing the landscapes, people, and daily life she observed. These works are notable for their empathetic portrayal of African subjects, avoiding the exoticizing or demeaning tropes common in colonial-era depictions. She also wrote about her experiences, continuing her critique of colonial practices and advocating for a more just relationship between France and its colonies. Her research also extended to the role of women in colonial households, highlighting her feminist and anti-racist perspectives.

Notable Works and Public Recognition

While Femme faisant du crochet is perhaps her most widely recognized painting due to its place in the Musée d'Orsay, other works also attest to her skill and vision. Her Bacchanale (1917), a work in charcoal and brown watercolor, showcases her draftsmanship and ability to handle dynamic compositions. Her landscapes, often depicting the sun-drenched scenery of Provence or the Mediterranean coast, are vibrant examples of Pointillist technique applied to capturing natural light.

Despite her active participation in the art world of her time, including exhibiting her work at venues like the Galerie Duret in Paris in 1907, Lucie Cousturier's artistic contributions were, for many decades after her death in 1925, largely overshadowed by her male contemporaries. However, recent scholarship and exhibitions have sought to rectify this oversight. A major retrospective at the Musée de Vernon in 2018, titled "Lucie Cousturier, peintre néo-impressionniste (1876-1925)," played a significant role in reintroducing her work to the public and affirming her place in art history. Another exhibition in 2019 at the Calvaire Chapel in Rousset, "De Signac à Bakor Bili," further highlighted her artistic journey and her engagement with African culture.

A Network of Innovators: Contemporaries and Influences

Lucie Cousturier operated within a rich network of artistic innovators. Her primary mentors, Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross, were central figures in Neo-Impressionism, and their influence on her technique and artistic philosophy was profound. She was also a contemporary and admirer of Georges Seurat, the movement's founder, whose systematic approach to color and composition laid the groundwork for Pointillism. Cousturier's writings on Seurat demonstrate her deep understanding of his innovative methods.

Her artistic circle and intellectual interests connected her to other key figures of Post-Impressionism. She knew and wrote about Paul Cézanne, whose emphasis on underlying structure and form was a touchstone for many avant-garde artists. While their styles differed, Cézanne's rigorous approach to painting resonated with the Neo-Impressionists' quest for order.

The broader Post-Impressionist milieu included artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, who, though pursuing different expressive paths, shared a desire to move beyond the naturalism of Impressionism. Van Gogh, in particular, experimented with Pointillist-like brushwork in some of his paintings, and his intense use of color finds echoes in the Neo-Impressionist pursuit of luminosity. Gauguin's interest in "primitive" cultures and non-Western art, while problematic by today's standards, reflects a wider turn-of-the-century fascination with cultures beyond Europe, a theme Cousturier would later engage with in a far more critical and empathetic manner.

Within the Neo-Impressionist group itself, artists like Maximilien Luce and Théo van Rysselberghe were important contemporaries who also explored and expanded upon Pointillist techniques. Camille Pissarro, one of the elder statesmen of Impressionism, briefly adopted the Neo-Impressionist style, demonstrating its appeal even to established artists. Cousturier's interactions with these figures would have been part of the vibrant exchange of ideas that characterized the Parisian art scene.

Her intellectual curiosity also led to connections beyond France. She had a notable exchange of ideas with the Australian Post-Impressionist painter Grace Cossington Smith. They discussed Cousturier's experiences abroad, and it's plausible that these cross-cultural artistic dialogues influenced Cossington Smith's own development.

Other contemporaries, while not directly part of the Neo-Impressionist circle, contributed to the diverse artistic landscape of the era. Odilon Redon, for example, explored Symbolism with his dreamlike and often mystical imagery, while Georges Rouault developed a powerful, expressive style that bordered on Fauvism and Expressionism. The early works of Henri Matisse and André Derain, who would become leaders of Fauvism, also show the influence of Neo-Impressionist color theory before they moved towards a bolder, more arbitrary use of color. Cousturier's life and work were thus situated within a dynamic period of artistic experimentation and cross-pollination.

A Legacy Reconsidered

For many years, Lucie Cousturier's name was primarily known to specialists in Neo-Impressionism or scholars of French colonial literature. Her gender, combined with the art historical focus on a few male "masters," contributed to her relative obscurity in broader art narratives. However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a concerted effort by art historians to rediscover and re-evaluate the contributions of women artists.

Cousturier's multifaceted career makes her a particularly compelling figure for this reassessment. She was not only a talented painter who made significant contributions to Neo-Impressionism but also an important intellectual whose writings offer valuable insights into the art and social issues of her time. Her anti-colonial activism, expressed with courage and clarity, positions her as a progressive thinker who was ahead of her time in many respects. The renewed interest in her work, exemplified by recent exhibitions and scholarly publications, is helping to restore her to her rightful place as a significant and influential figure in French cultural history.

Conclusion: A Woman of Art and Conviction

Lucie Cousturier was a remarkable individual whose life and work transcended traditional boundaries. As an artist, she masterfully employed the demanding techniques of Neo-Impressionism to create works of luminous beauty and quiet introspection. As a writer and theorist, she provided invaluable documentation and analysis of one of the key avant-garde movements of her era. As an activist, she used her voice and her experiences to challenge injustice and advocate for a more humane world.

Her legacy is one of artistic innovation, intellectual rigor, and profound social conscience. The increasing recognition of Lucie Cousturier's contributions enriches our understanding of Neo-Impressionism, the complexities of the colonial era, and the vital role that women artists and intellectuals played in shaping the cultural and political landscape of the early 20th century. Her story is a testament to the power of art and ideas to illuminate the world and inspire change.