Jacopo Carucci, more famously known as Jacopo da Pontormo, or simply Pontormo, stands as one of the most intriguing and pivotal figures of 16th-century Italian art. Born Jacopo Carucci in 1494 in the village of Pontorme, near Empoli in Tuscany, he derived his moniker from his birthplace, a common practice for artists of the era. His life (1494-1557) spanned a period of immense artistic, political, and religious upheaval, witnessing the zenith of the High Renaissance and the subsequent emergence of Mannerism, a style he profoundly shaped. Pontormo's work is characterized by its departure from the classical harmony and naturalism of his predecessors, venturing into a realm of heightened emotionalism, ambiguous space, elongated forms, and often unsettling color palettes. He was a painter of profound originality, whose deeply personal and often eccentric vision left an indelible mark on the trajectory of Western art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Pontormo's early life was marked by tragedy. His father, Bartolomeo di Jacopo di Martino Carucci, was a painter, though little is known of his work. Orphaned at a young age – losing his father, mother, and grandfather in quick succession – he was eventually taken under the care of his grandmother and later, it is believed, by the Florentine state or a guardian. This early experience of loss may have contributed to the introspective and melancholic temperament that characterized his adult life and art.

Around 1508, the young Jacopo arrived in Florence, the vibrant heart of the Renaissance. His artistic education was eclectic, reflecting the rich tapestry of talent in the city. According to Giorgio Vasari, the 16th-century artist and biographer whose Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects remains a primary source for this period, Pontormo briefly passed through the workshops of several masters. These included the aging Leonardo da Vinci, whose sfumato and psychological depth would have been an early, if fleeting, influence. He also spent time with Mariotto Albertinelli and Piero di Cosimo, the latter known for his idiosyncratic and imaginative mythological scenes.

However, the most significant apprenticeship was with Andrea del Sarto, a leading painter of the High Renaissance in Florence, whose workshop Pontormo entered around 1512. Del Sarto was renowned for his harmonious compositions, graceful figures, and rich color. Under his tutelage, Pontormo honed his technical skills. Other notable artists associated with Sarto's workshop around this time, or slightly later, included Rosso Fiorentino, who would also become a key figure in early Mannerism, and Vasari himself. Pontormo’s early works, such as the Madonna and Child with Saints for the church of San Ruffillo (c. 1514, now lost but known through copies and descriptions), showed a clear debt to Sarto's style, yet already hinted at a more intense and restless energy.

The Break with Tradition and Early Commissions

Pontormo's association with Andrea del Sarto was fruitful but ultimately short-lived. Vasari recounts that Sarto became envious of his pupil's burgeoning talent, particularly after Pontormo completed a Faith and Charity fresco for the Santissima Annunziata, which garnered considerable praise. Whether due to Sarto's jealousy or Pontormo's own burgeoning independence, he soon struck out on his own.

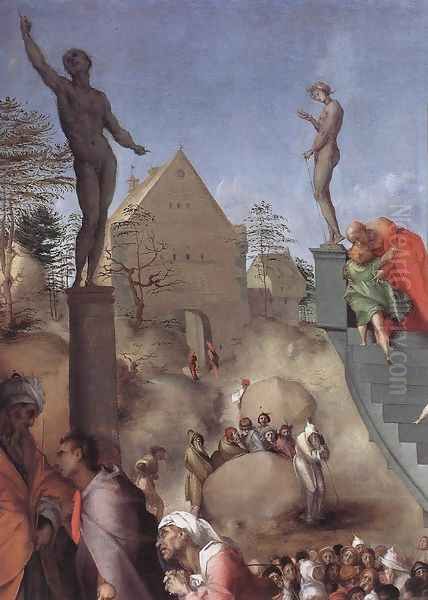

A significant early commission that showcased his developing style was the decoration of the nuptial chamber of Pierfrancesco Borgherini and Margherita Acciaiuoli, a project undertaken between 1515 and 1516. Pontormo contributed panels depicting scenes from the life of Joseph, including Joseph in Egypt (National Gallery, London). These works, while still showing some influence from Sarto and Fra Bartolommeo, exhibit a new dynamism, crowded compositions, and an emerging interest in expressive, elongated figures. Other artists who contributed to this prestigious project included Andrea del Sarto, Francesco Granacci, and Bacchiacca (Francesco Ubertini).

Around 1518, Pontormo painted the Visdomini Altarpiece (Madonna and Child with Saints Joseph, John the Evangelist, Francis, and James) for the Church of San Michele Visdomini in Florence. This work is often cited as a crucial step in his departure from High Renaissance classicism. The figures are tightly packed, their gazes intense and varied, creating a sense of unease and psychological complexity. The traditional serene harmony is replaced by a palpable emotional tension.

The Certosa del Galluzzo and Northern Influences

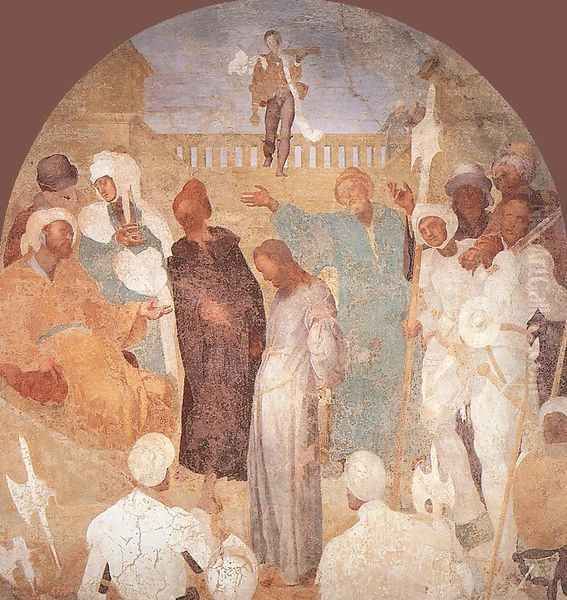

A pivotal period in Pontormo's artistic development occurred between 1523 and 1525 when he, along with his devoted pupil Agnolo Bronzino, retreated to the Carthusian monastery of Certosa del Galluzzo, just outside Florence, possibly to escape an outbreak of plague. Here, he executed a series of frescoes depicting the Passion of Christ. These works reveal a profound shift in his style, heavily influenced by the prints of the German master Albrecht Dürer.

The angularity of the figures, the heightened emotionalism, and the dramatic intensity of Dürer's graphic work resonated deeply with Pontormo's own artistic inclinations. The Certosa frescoes, such as the Agony in the Garden and Christ Before Pilate, display a starkness, a pathos, and a departure from Italianate grace that was quite radical for its time. The elongated proportions and the almost spectral quality of the figures mark a definitive move into Mannerist territory. This absorption of Northern European influences was not unique to Pontormo – artists like Luca Signorelli had earlier shown interest – but Pontormo integrated it in a deeply personal way that transformed his art.

Masterworks of High Mannerism: The Capponi Chapel

Perhaps Pontormo's most celebrated and iconic achievement is the decoration of the Capponi Chapel in the church of Santa Felicita in Florence, undertaken between 1525 and 1528. This commission included the breathtaking altarpiece, the Deposition from the Cross (or Lamentation over the Dead Christ), an Annunciation fresco on the west wall, and tondi in the pendentives depicting the Four Evangelists, with Bronzino likely assisting on some parts.

The Deposition is a cornerstone of Mannerist art. It defies traditional iconography and compositional norms. There is no cross, no clearly defined landscape, only a swirling vortex of figures rendered in an astonishing palette of pastel pinks, blues, and greens. The figures, elongated and seemingly weightless, convey an almost unbearable sense of grief and bewilderment. Christ's body is pale and ethereal, supported by figures whose poses are both graceful and precarious. The Virgin Mary swoons in a cascade of blue drapery. The emotional intensity is palpable, drawing the viewer into a scene of profound spiritual anguish. The ambiguity of the subject – is it a Deposition or a Lamentation, or an Entombment? – adds to its unsettling power. The work’s radical departure from the balanced, stable compositions of High Renaissance masters like Raphael or the early Michelangelo is striking.

The Annunciation fresco in the same chapel, though perhaps less revolutionary than the Deposition, shares its ethereal quality and elongated figures. The Virgin and the Archangel Gabriel are depicted in a moment of suspended animation, their forms elegant and otherworldly. The Capponi Chapel as a whole represents Pontormo at the height of his powers, creating a deeply spiritual and aesthetically unique environment.

The Visitation of Carmignano

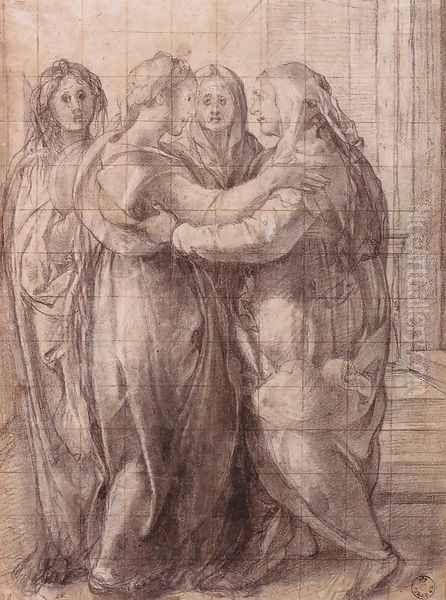

Another key work from this mature period is The Visitation (c. 1528-1529), painted for the parish church of San Michele Arcangelo in Carmignano, a town near Florence. This painting depicts the meeting of the Virgin Mary and Saint Elizabeth, both pregnant (Mary with Jesus, Elizabeth with John the Baptist). The four figures – Mary, Elizabeth, and two attendants – are monumental, almost statuesque, yet possess an inner dynamism.

Their voluminous draperies, rendered in vibrant, almost acidic colors, swirl around them, creating a sense of movement and emotional intensity. The figures seem to loom out of the canvas, their expressions enigmatic. The composition is tightly packed, with the figures dominating the pictorial space. The dreamlike quality and the psychological intensity of the encounter are characteristic of Pontormo's mature Mannerist style. This work, like the Deposition, showcases his ability to imbue traditional religious scenes with a profound and unsettling personal vision.

Portraiture: A Window to the Soul

Pontormo was also a highly accomplished portraitist. His portraits are renowned for their psychological acuity, capturing the sitter's inner life with an unnerving intensity. He often depicted his subjects with a sense of melancholy or introspection, their elongated forms and pale complexions contributing to an air of aristocratic refinement and nervous sensibility.

Notable examples include the Portrait of a Halberdier (c. 1528-1530, Getty Museum), a striking depiction of a young soldier, possibly Francesco Guardi. The youth's confident yet slightly wary gaze, combined with the elegant, elongated proportions, makes for a compelling image. Other significant portraits include those of members of the Medici family, such as Cosimo il Vecchio (c. 1518-1520) and later, portraits of Duke Cosimo I de' Medici and Maria Salviati. His portraits often feature ambiguous backgrounds and a focus on the sitter's hands and facial expression, conveying a sense of unease or quiet contemplation that was a hallmark of Mannerist portraiture, a style also masterfully practiced by his pupil Bronzino, though Bronzino's portraits often tend towards a more polished, aloof, and mask-like perfection. Pontormo's approach can be contrasted with the more robust and direct portraiture of Venetian masters like Titian.

Later Years and the Lost San Lorenzo Frescoes

The latter part of Pontormo's career was dominated by a large-scale commission to decorate the choir of the Medici family church, San Lorenzo, in Florence. He worked on these frescoes, depicting scenes from Genesis and the Last Judgment, from 1546 until his death in 1557. Agnolo Bronzino completed the work after his master's passing. Sadly, these frescoes were destroyed in 1738 during a renovation of the church.

Our knowledge of these lost works comes primarily from Pontormo's own diary, which he kept during the last two years of his life (1554-1556), and from drawings and descriptions by Vasari. The diary is a fascinating document, offering glimpses into Pontormo's solitary and obsessive personality, his meticulous recording of his diet, his anxieties about his health, and his progress on the San Lorenzo project. Vasari was critical of the San Lorenzo frescoes, finding them confusing in their composition and overly influenced by Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, yet lacking its grandeur and clarity. He described Pontormo's figures as excessively contorted and the overall effect as melancholic. The loss of these frescoes is a significant lacuna in our understanding of Pontormo's late style, a period where he seems to have pushed his artistic vision to its limits, perhaps even into a realm of profound personal obsession.

The Man Behind the Art: Personality and Anecdotes

Vasari's biography paints a picture of Pontormo as a reclusive, eccentric, and melancholic individual. He was reportedly fearful of death and illness, and intensely private about his work, often working in seclusion and refusing entry to his studio, even to patrons. Vasari describes how Pontormo would pull up a wooden ladder to his upper-story room to ensure his solitude.

His diary further illuminates this solitary existence. It is filled with mundane details of his daily meals (often meager), his physical ailments, and his anxieties. Yet, it also reveals his dedication to his art. This introspective and somewhat neurotic personality seems to find expression in the unsettling beauty and emotional intensity of his paintings. While Vasari's accounts can sometimes be colored by his own artistic biases (he was a proponent of a more classical and "correct" style of painting, often critiquing the perceived excesses of Mannerism), the consistency between his descriptions and Pontormo's own diary entries suggests a core truth to this portrayal. His solitary nature contrasts with the more gregarious personalities of artists like Raphael or the politically astute Titian.

In 2004, Italian director Giovanni Fago brought Pontormo's life to the screen in the film Pontormo, un amore eretico (Pontormo, A Heretical Love), which explored his artistic struggles, his personality, and the religious and political climate of his time, including the influence of the Reformation.

Pontormo's Relationship with Contemporaries

Pontormo's career unfolded in a Florence teeming with artistic talent. His primary teacher, Andrea del Sarto, provided a solid foundation in High Renaissance principles. However, Pontormo, along with his contemporary Rosso Fiorentino, quickly diverged from Sarto's harmonious style, pioneering the more agitated and subjective language of Mannerism. Rosso, like Pontormo, was known for his expressive distortions and unconventional color choices, though his path led him to France to work for King Francis I at Fontainebleau.

Michelangelo was a towering figure whose influence Pontormo deeply felt, particularly in his later works like the San Lorenzo frescoes. Pontormo admired Michelangelo's powerful nudes and dramatic compositions, though his interpretation of these elements was filtered through his own unique sensibility. Unlike Michelangelo, who also excelled as a sculptor and architect, Pontormo remained primarily a painter.

His most significant artistic relationship was with his pupil, Agnolo Bronzino. Bronzino absorbed much from his master, particularly the elongated forms and polished surfaces, but developed his own distinct style, characterized by a cool, detached elegance and impeccable technique, especially evident in his renowned Medici portraits. Bronzino remained loyal to Pontormo throughout his life, assisting him on numerous projects and completing the San Lorenzo frescoes.

Other Florentine contemporaries included Francesco Salviati and Giorgio Vasari. Vasari, while an admirer of Pontormo's talent, often expressed reservations about the more extreme aspects of his style, reflecting the ongoing debate about the direction of art after the High Renaissance. Pontormo also would have been aware of the work of Sienese Mannerists like Domenico Beccafumi, who developed a parallel, highly individualistic style. Beyond Florence, the artistic landscape included Venetian giants like Titian and Tintoretto (the latter also displaying strong Mannerist tendencies), and Roman figures like Giulio Romano, Raphael's pupil, who became a key Mannerist in Mantua.

Artistic Style and Characteristics: A Summary

Pontormo's art is a defining expression of early Florentine Mannerism. Key characteristics include:

Elongated and Attenuated Figures: His figures often possess an unnatural length and slenderness, contributing to their ethereal and graceful, yet sometimes unsettling, appearance. This is a hallmark of the figura serpentinata (serpentine figure) favored by Mannerists.

Ambiguous Space and Composition: He often rejected the rational perspective and balanced compositions of the High Renaissance. His figures may float in undefined spaces, and compositions can be crowded, asymmetrical, or vertiginous, creating a sense of instability or psychological tension.

Unconventional Color Palettes: Pontormo employed striking and often non-naturalistic colors – vibrant pinks, acidic greens, pale blues, and sharp oranges. These color choices enhance the emotional and otherworldly quality of his scenes.

Emotional Intensity and Psychological Depth: His works are imbued with a profound emotionalism, ranging from ecstatic spirituality to deep melancholy and anxiety. His portraits, in particular, reveal a keen insight into the sitter's psyche.

Influence of Northern Art: His engagement with Dürer's prints was transformative, introducing a new level of angularity and expressive intensity into his work.

Individuality and Eccentricity: Pontormo's style is highly personal and idiosyncratic, reflecting his unique artistic vision and, perhaps, his reclusive personality. He was less concerned with classical ideals of beauty than with conveying complex emotional and spiritual states.

Influence and Legacy

Pontormo's immediate influence was most strongly felt by his pupil Bronzino, who adapted his master's style into a more courtly and polished form of Mannerism. Through Bronzino and other Florentine artists, Pontormo's innovations contributed to the broader dissemination of Mannerist principles.

While Mannerism as a style eventually gave way to the Baroque in the early 17th century, Pontormo's emphasis on emotional intensity and subjective vision can be seen as prefiguring certain aspects of later art. Artists like El Greco, who also employed elongated figures and expressive distortion to convey spiritual fervor, share some affinities with Pontormo. The dramatic lighting and psychological intensity found in the works of Caravaggio, a key figure of the early Baroque, also resonate with Pontormo's departure from High Renaissance serenity.

For a period, Pontormo's reputation, like that of many Mannerists, was somewhat eclipsed, particularly during eras that favored classicism. However, the 20th century saw a significant re-evaluation of Mannerism, and Pontormo was rediscovered as a highly original and compelling master. His work is now recognized for its daring innovation, its profound psychological depth, and its haunting beauty. Art historians like John Shearman and Frederick Hartt played crucial roles in deepening the modern understanding of Mannerism and Pontormo's place within it. His art continues to fascinate viewers with its enigmatic quality and its powerful expression of the human condition during a time of profound change.

Conclusion

Jacopo Pontormo remains a captivating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the history of art. A product of the Florentine High Renaissance, he became one of its most radical innovators, forging a deeply personal style that helped define early Mannerism. His paintings, with their elongated figures, unsettling colors, ambiguous spaces, and profound emotional intensity, broke decisively with the classical harmony of his predecessors. From the poignant Deposition in the Capponi Chapel to his psychologically charged portraits and the lost, ambitious frescoes of San Lorenzo, Pontormo's work reflects a restless, introspective spirit grappling with the artistic and spiritual anxieties of his age. His legacy is that of a true original, an artist who dared to look beyond established conventions to create a visual language uniquely his own, leaving behind a body of work that continues to challenge, move, and inspire.