Frank William Warwick Topham (1838-1924) stands as a notable figure within the rich tapestry of British Victorian art. A painter proficient in both watercolour and oils, he carved a niche for himself through his evocative depictions of historical events, literary narratives, and poignant genre scenes. His career spanned a period of significant artistic evolution and societal change, and his works offer a valuable window into the tastes, preoccupations, and artistic conventions of his time. Son of the established watercolourist Francis William Topham, he inherited a passion for art and honed his skills to become a respected artist in his own right, contributing to the vibrant artistic milieu of 19th-century Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in London on April 15, 1838, Frank William Warwick Topham was immersed in an artistic environment from his earliest years. His father, Francis William Topham (1808-1877), was a distinguished member of the Old Watercolour Society (later the Royal Watercolour Society) and renowned for his charming genre scenes, often inspired by his travels in Spain and Ireland. This paternal influence undoubtedly played a crucial role in shaping young Frank's artistic inclinations and providing him with initial guidance.

To formalize his training, Topham enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. This institution was the cornerstone of artistic education in Britain, providing rigorous instruction in drawing, anatomy, and the principles of academic art. Here, he would have studied alongside other aspiring artists and been exposed to the prevailing artistic theories and practices. The curriculum emphasized the importance of classical ideals, meticulous draftsmanship, and the grand tradition of history painting, all of which would inform Topham's subsequent work. His time at the Royal Academy Schools equipped him with the technical proficiency and artistic grounding necessary to embark on a professional career.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Frank William Warwick Topham developed a style characterized by careful composition, attention to detail, and a strong narrative sense. While adept in oils, he, like his father, showed a particular affinity for watercolours, a medium in which British artists had long excelled. His watercolours often display a luminous quality and a fluid handling of the medium, while his oil paintings possess a richer texture and depth of colour suitable for more dramatic subjects.

Topham's thematic interests were diverse but often gravitated towards subjects that allowed for storytelling and emotional expression. Historical scenes were a significant part of his oeuvre. These were not always grand, epic battles, but often more intimate or human-focused moments within a historical context. He was drawn to periods such as Roman history, as seen in works like The Fall of Licinius, and significant events in British history, most notably the Great Plague of London.

Literary subjects also held a strong appeal for Topham. The Victorian era witnessed a fervent interest in the works of William Shakespeare, Sir Walter Scott, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, whose writings provided rich source material for artists. Topham contributed to this trend with paintings inspired by iconic literary works, demonstrating his ability to translate textual narratives into compelling visual compositions. Arthurian legends, revived in popularity during this period, also featured in his work.

Beyond history and literature, Topham also engaged with genre painting, depicting scenes of everyday life, often with a sentimental or anecdotal quality. These works, such as The Village Genius, resonated with Victorian audiences who appreciated art that told a story or conveyed a moral message. A recurring motif in some of his works is the exploration of the human body and its connection to broader themes of human experience, value, and community.

Masterpieces and Notable Works

Several key paintings define Frank William Warwick Topham's contribution to Victorian art, showcasing his skill and thematic range.

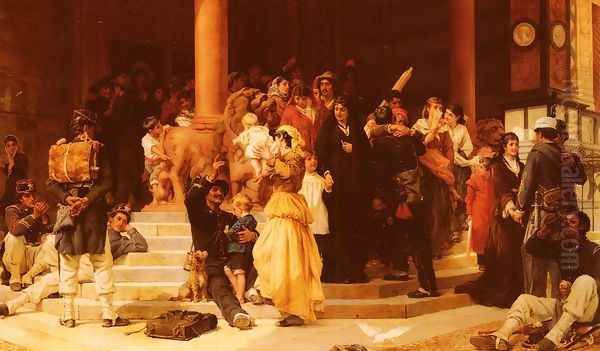

Rescued from the Plague, London, 1665

This powerful painting is arguably one of Topham's most impactful historical works. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1880, it depicts a dramatic and poignant scene from the Great Plague of London. The composition typically focuses on human figures in distress and the acts of heroism or compassion amidst the crisis. Such subjects were popular in the Victorian era, appealing to the public's fascination with history and their appreciation for narratives of human suffering and resilience. The painting highlights Topham's ability to convey strong emotion and create a vivid sense of historical atmosphere. It explores themes of human connection, mortality, and the fragility of life, resonating with Victorian sensibilities about public health and social responsibility, themes also explored by artists like Luke Fildes in his social realist works, albeit from a contemporary perspective.

Voyage of King Arthur and Morgan Le Fay to the Isle of Avalon

Reflecting the Victorian revival of interest in Arthurian legends, spurred by Tennyson's "Idylls of the King," this painting delves into the mystical and romantic world of Camelot. The subject of Arthur's final journey to Avalon, accompanied by Morgan Le Fay and other queens, was a popular one, depicted by various artists including Pre-Raphaelites like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, and later by John William Waterhouse. Topham's interpretation would have focused on the ethereal quality of the scene, the sorrow of departure, and the promise of healing in the mythical isle. Such works allowed artists to explore themes of chivalry, loss, and the supernatural, appealing to the romantic imagination of the Victorian audience.

The Village Genius

Exhibited in 1884, The Village Genius (sometimes referred to as The Village) is a fine example of Topham's work in the genre painting tradition. These scenes often depicted rural life, childhood, or moments of quiet domesticity, imbued with a sense of charm or moral instruction. The Village Genius likely portrays a young, aspiring individual from a humble background, perhaps displaying an early talent for art or another intellectual pursuit, admired by family or community members. Such themes of self-improvement and innate talent resonated with Victorian ideals of progress and opportunity. This work can be seen in the tradition of artists like Thomas Webster or William Mulready, who specialized in charming and anecdotal genre scenes.

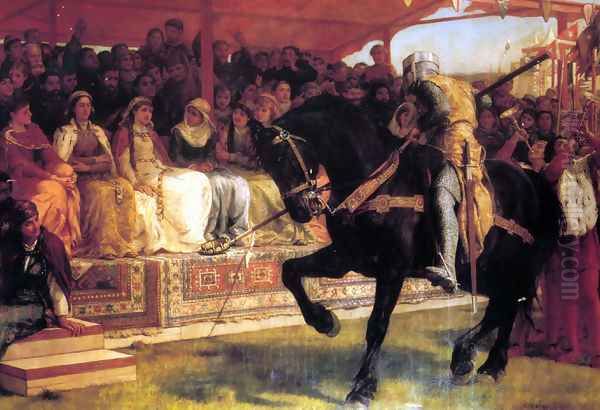

Literary Illustrations: Ivanhoe and The Taming of the Shrew

Topham also turned his brush to the works of Sir Walter Scott and William Shakespeare. His painting The Queen of the Tournament: Ivanhoe captures a moment from Scott's famous historical romance, a novel that profoundly influenced Victorian culture and provided countless subjects for artists. The pageantry, chivalry, and romanticism of Scott's world were well-suited to Topham's narrative style.

Similarly, his depiction of a scene from Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew demonstrates his engagement with the Bard, whose plays were a constant source of inspiration for Victorian painters. Artists like Daniel Maclise, Charles Robert Leslie, and members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, such as John Everett Millais with his Ophelia, frequently drew upon Shakespearean themes. Topham's contribution would have focused on the dramatic interplay between characters and the rich historical costuming.

Other Significant Works

Other notable paintings by Topham include Drawing For Military Service, Modern Italy (1878), which suggests an interest in contemporary European events and perhaps a more socio-political commentary. Home! After Service (1889) likely depicts a scene of return and domestic reunion, a common and emotionally resonant theme in Victorian art. The Ruins of Pompeii indicates his engagement with classical antiquity, a popular subject for artists traveling on the Grand Tour or inspired by archaeological discoveries. Women and a Healing Source hints at a more allegorical or symbolic theme, possibly touching upon faith, nature, or folklore.

Exhibitions, Travels, and Recognition

Frank William Warwick Topham was a regular exhibitor at prominent London art institutions, which was crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success during the Victorian era. He frequently showed his works at the Royal Academy of Arts, the most prestigious venue for artists in Britain. His inclusion in these annual exhibitions signifies a level of peer recognition and an adherence to the standards of academic art.

He also exhibited with the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours, where his work The Village Genius was shown at their exhibition held in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. This affiliation underscores his proficiency and commitment to the watercolour medium, following in his father's footsteps.

Like many artists of his time, Topham traveled, seeking inspiration and new subjects. He is known to have lived and painted in Italy and France. Italy, with its classical ruins, Renaissance masterpieces, and picturesque landscapes, was a particularly strong draw for British artists. France, especially Paris, was the burgeoning center of new artistic movements. These experiences abroad would have broadened his artistic horizons and potentially influenced his palette and subject matter. His later life saw him reside in Spain, where he eventually passed away in 1924. This connection to Spain echoes his father's well-known Spanish subjects.

Topham in the Context of Victorian Art

To fully appreciate Frank William Warwick Topham's work, it is essential to place him within the broader context of Victorian art. The era was characterized by a remarkable diversity of styles and themes. The Royal Academy, while dominant, faced challenges from emerging movements.

Topham's historical and literary paintings align with the academic tradition upheld by figures like Lord Frederic Leighton, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Sir Edward Poynter, who produced grand canvases depicting classical, biblical, and historical subjects with meticulous detail and technical brilliance. While Topham may not have worked on the same monumental scale as these titans of High Victorian art, he shared their commitment to narrative clarity and historical accuracy.

His engagement with literary themes, particularly Shakespeare and Arthurian legends, connects him to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt) and their followers, such as Edward Burne-Jones and John William Waterhouse. These artists sought to imbue their literary and medieval subjects with intense emotion, symbolism, and a jewel-like richness of detail. Topham's approach was generally more straightforwardly narrative than the often complex symbolism of the Pre-Raphaelites.

In the realm of genre painting, Topham's work can be compared to that of artists like William Powell Frith, known for his panoramic scenes of modern life (e.g., The Derby Day), or Luke Fildes and Hubert von Herkomer, who later brought a greater degree of social realism to genre subjects. Topham's genre scenes tended towards the more sentimental and anecdotal, a popular vein in Victorian art.

The mention of a collaboration with an artist named "Frederick" in France around 1844, as noted in some sources, likely refers to his father, Francis William Topham, working with Frederick Goodall (1822-1904). Goodall was a contemporary of the elder Topham, known for his genre scenes and later, his large-scale Egyptian subjects. If the younger Frank Topham also had contact with Goodall or artists of his father's circle, it would have further enriched his artistic development. Other contemporaries whose work provides context include Myles Birket Foster, a master of idyllic watercolour landscapes and rustic genre, and Helen Allingham, celebrated for her charming depictions of English cottages and country life. Even an artist like James Tissot, who focused on elegant scenes of contemporary high society, operated within the same broad Victorian art world, showcasing its diverse interests.

Later Life and Legacy

Frank William Warwick Topham continued to paint throughout his life, adapting to changing artistic tastes while largely remaining true to his narrative and illustrative style. He spent his final years in Spain, a country that had so inspired his father, and passed away in Cordova on March 31, 1924.

In art historical evaluations, Topham is regarded as a competent and skilled painter who contributed creditably to the Victorian art scene. He may not have been an innovator on the scale of Turner or the Pre-Raphaelites, nor did he achieve the immense public acclaim of Leighton or Millais. However, his work is representative of the strong tradition of narrative painting that flourished in 19th-century Britain. His paintings are valued for their craftsmanship, their engaging storytelling, and the insight they offer into Victorian culture, literary tastes, and historical consciousness.

His works continue to appear at auctions, indicating an ongoing appreciation among collectors of Victorian art. Paintings like Rescued from the Plague and his literary illustrations remain compelling examples of their respective genres.

Conclusion

Frank William Warwick Topham was an artist who successfully navigated the demands and opportunities of the Victorian art world. Steeped in the academic tradition yet responsive to popular literary and historical themes, he produced a body of work that entertained, instructed, and moved his contemporaries. His paintings of dramatic historical episodes, romantic literary scenes, and charming genre vignettes capture the spirit of his age. As a skilled practitioner in both oil and watercolour, and as the son of an accomplished artist, he upheld a family tradition while forging his own distinct artistic identity. His legacy is that of a dedicated and talented painter whose works continue to provide a visual gateway to the multifaceted world of 19th-century Britain. His contributions, while perhaps not revolutionary, were a solid and respected part of the artistic fabric of his time, reflecting the era's deep engagement with storytelling in visual form.