Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys stands as a significant, if sometimes enigmatic, figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. Active during a period of immense artistic ferment, Sandys navigated the currents of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the lingering traditions of the Norwich School, forging a distinctive style characterized by meticulous detail, psychological depth, and a powerful, often unsettling, portrayal of human emotion, particularly through his iconic female figures. His contributions as a painter, illustrator, and draughtsman, though not always met with widespread contemporary financial success, have secured him a lasting place in art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Norwich

Born on May 1, 1829, in Norwich, a city with a rich artistic heritage, Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys (originally Sands, he later added the 'y') was immersed in art from his earliest years. His father, Anthony Sands, was himself a painter, providing young Frederick with his initial instruction and fostering an environment where artistic pursuits were encouraged. This early exposure to the practicalities of painting and drawing in his father's studio undoubtedly laid the groundwork for the technical proficiency that would become a hallmark of his mature work.

Norwich at this time was still under the influence of the Norwich School of painters, a regional movement that had flourished in the early part of the nineteenth century, led by figures such as John Crome and John Sell Cotman. This school was renowned for its dedication to landscape painting, emphasizing direct observation of nature and a subtle, often atmospheric, rendering of the local Norfolk scenery. While Sandys would later become more famous for his figure paintings and portraits, the Norwich School's emphasis on careful observation and detailed rendering likely contributed to his own meticulous approach.

In 1846, Sandys formalized his artistic education by enrolling at the Norwich School of Design. His talent was quickly recognized; in the same year, he received accolades from the Royal Society of Arts in London for a drawing, an early indication of his burgeoning skill. He continued to develop his abilities, exhibiting his first work at the Norwich Institution in 1847. These formative years in Norwich provided him with a solid technical foundation and an appreciation for detailed craftsmanship that would serve him throughout his career.

The Move to London and Pre-Raphaelite Affiliations

By 1851, Sandys, like many ambitious provincial artists of his time, made the pivotal decision to move to London, the vibrant center of the British art world. This move exposed him to a wider range of artistic influences and opportunities. He began exhibiting at the prestigious Royal Academy, a crucial step for any artist seeking recognition and patronage. His early London works included portraits and subject pictures, demonstrating his growing confidence and technical command.

It was in London that Sandys came into contact with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), a group of young artists who had caused a sensation in the late 1840s and early 1850s with their radical rejection of the prevailing academic conventions, particularly those derived from the followers of Raphael. Led by figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, the Pre-Raphaelites advocated a return to the art of the early Italian Renaissance, emphasizing brilliant color, intricate detail, complex compositions, and subjects often drawn from literature, religion, and medieval romance.

Sandys was never an official member of the PRB, but he became closely associated with the circle, particularly with Rossetti. In 1857, Sandys created a satirical print titled The Nightmare, a clever caricature of Millais's controversial painting Sir Isumbras at the Ford. Rather than causing offense, the print amused the Pre-Raphaelites and served as an introduction to Rossetti, who admired Sandys's draughtsmanship. This led to a period of close friendship and artistic exchange, with Sandys even sharing Rossetti's home at 16 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, for a time in the 1860s. The influence of Pre-Raphaelitism is evident in Sandys's heightened attention to detail, his use of vibrant, jewel-like colors, and his choice of literary and mythological themes.

Other artists within or adjacent to the Pre-Raphaelite circle whose work shares affinities or provided context for Sandys include Ford Madox Brown, with his moralizing contemporary subjects, Edward Burne-Jones, who further developed the romantic and medievalist strands of the movement, and William Morris, whose design work and socialist ideals also intersected with the group. Sandys, however, maintained a unique voice, often infusing his Pre-Raphaelite-inspired works with a harder, more incisive quality.

Defining an Artistic Style: Precision, Intensity, and the Femme Fatale

Anthony Frederick Sandys's artistic style is distinguished by its extraordinary precision and intensity. His draughtsmanship was impeccable, characterized by a sharp, clear line and an almost obsessive attention to detail. Whether working in oils, watercolors, chalks, or creating wood engravings, Sandys demonstrated a remarkable control over his medium. This meticulousness extended to every aspect of his compositions, from the rendering of individual strands of hair and the intricate patterns of fabric to the subtle modulations of light and shadow that define form.

His color palette, particularly in his oil paintings, was often rich and luminous, echoing the Pre-Raphaelite preference for bright, clear hues. However, Sandys also demonstrated a mastery of more somber tones, especially in his chalk portraits and wood engravings, where he exploited the dramatic potential of chiaroscuro.

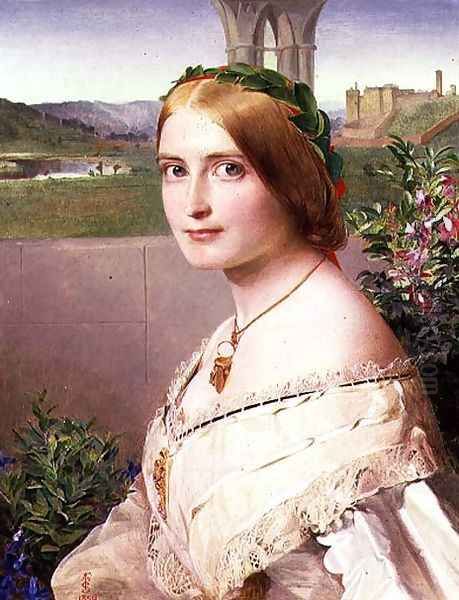

A recurring and central theme in Sandys's oeuvre is the portrayal of women. He was particularly drawn to strong, often enigmatic or dangerous, female figures from mythology, literature, and history. His women are rarely passive or demure; instead, they exude an intense, often brooding, sensuality and psychological complexity. He became one of the foremost Victorian painters of the "femme fatale," a type that fascinated the nineteenth-century imagination. These figures, such as Medea, Morgan le Fay, and Vivien, are depicted with a compelling blend of beauty and menace, their allure intertwined with a sense of destructive power. This fascination with powerful and often morally ambiguous female characters aligns him with other artists of the period, like Rossetti and Burne-Jones, who also explored similar archetypes.

Beyond mythological figures, Sandys also produced striking portraits of contemporary women, often imbuing them with a similar intensity and psychological presence. His ability to capture not just a likeness but also the inner life of his sitters was remarkable.

Masterpieces and Key Works: A Legacy in Paint and Print

Sandys's body of work, though not as extensive as some of his contemporaries due to his painstaking methods, includes several masterpieces that exemplify his unique vision and technical brilliance.

Mythological and Literary Subjects:

Among his most celebrated paintings is Medea (1868, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery). This powerful depiction of the sorceress from Greek mythology shows Medea in the act of concocting a poisonous brew, her face a mask of intense concentration and malevolent intent. The painting is notable for its rich, dark colors, the meticulous rendering of the still-life elements associated with her witchcraft, and the palpable sense of psychological tension. The work was famously rejected by the Royal Academy in 1868, possibly due to its unsettling subject matter or internal politics, but was exhibited the following year to considerable acclaim.

Another significant work is Vivien (1863, Manchester Art Gallery), which portrays the enchantress from Arthurian legend who ensnares Merlin. Sandys depicts Vivien with a captivating, almost hypnotic gaze, her red hair (a common feature in Pre-Raphaelite depictions of alluring women) cascading around her. The intricate details of her gown and the symbolic inclusion of an apple contribute to the painting's rich allegorical texture.

Morgan le Fay (1864, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery) is another formidable Arthurian sorceress, depicted by Sandys with an air of regal power and arcane knowledge. The painting showcases his skill in rendering elaborate textiles and his ability to create an atmosphere of medieval romance and dark magic.

Love's Shadow (c. 1867, private collection) is a more intimate but equally intense work, featuring a close-up of a woman's face, partially obscured by pansies, symbolizing thoughts of love. The direct gaze and the rich, sensual rendering of the flowers and hair are characteristic of Sandys's approach.

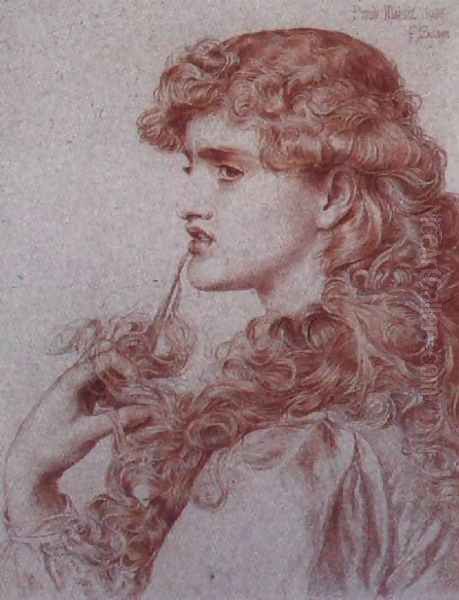

Proud Maisie (1867, private collection), inspired by a ballad by Sir Walter Scott, depicts a young woman adorned with jewels, her expression a mixture of hauteur and melancholy. The painting is a tour-de-force of detailed execution, particularly in the rendering of the textures of fabric, hair, and precious stones.

Portraits:

Sandys was also a highly accomplished portraitist. His chalk portraits, in particular, are renowned for their sensitivity and psychological insight. He drew many prominent figures of his day, as well as friends and family. These portraits, often executed in colored chalks on tinted paper, combine a high degree of finish with a sense of immediacy and vitality. Notable examples include portraits of fellow artists like Simeon Solomon and poets such as Algernon Charles Swinburne. His portrait Mrs Mary Elizabeth Barstow (1867) and Adelaide Mary (1867) are fine examples of his ability to capture individual character with precision.

Wood Engravings and Illustrations:

Sandys made a significant contribution to the "Golden Age" of British illustration in the 1860s. He produced a relatively small number of wood engravings, but they are considered among the finest of the period. Working for periodicals such as Once a Week, The Cornhill Magazine, and The Shilling Magazine, Sandys created designs that were then meticulously cut onto woodblocks by skilled engravers like Joseph Swain and the Dalziel Brothers.

His illustrations are characterized by their dramatic power, technical virtuosity, and often macabre or intensely emotional subject matter. Works such as The Old Chartist (1862), Until Her Death (1862), Amor Mundi (1865), and The Portent (1860s) are masterpieces of the medium. His illustration for Christina Rossetti's poem "Amor Mundi" is particularly striking, depicting a man and woman lured towards a decaying corpse by a seductive figure. He also provided illustrations for Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poems, including a notable design for The Lady of Shalott, a subject beloved by the Pre-Raphaelites. His illustrative style, with its strong lines and dramatic compositions, influenced other illustrators of the period, and his technical demands pushed the boundaries of what wood engravers could achieve. His work in this field can be compared to that of Millais, Rossetti, and Frederick Walker, who were also prominent illustrators.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and Influences

Sandys's career was interwoven with the lives and works of many leading figures in the Victorian art and literary worlds. His closest artistic association was undoubtedly with Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Their friendship, though sometimes strained, was mutually influential. Sandys's meticulous draughtsmanship may have inspired Rossetti, while Rossetti's poetic imagination and penchant for romantic and medieval themes certainly resonated with Sandys. They shared models, including the Romani woman Keomi Gray, who appears in several of Sandys's works and was also known to Rossetti.

Beyond Rossetti, Sandys interacted with other Pre-Raphaelites and their associates. He knew William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, the other founding members of the PRB. He was also acquainted with the critic John Ruskin, the great champion of the Pre-Raphaelites, though Ruskin's praise for Sandys was not as effusive as it was for some others. His circle included poets like Algernon Charles Swinburne, whose portrait he drew, and George Meredith.

His work as an illustrator brought him into contact with writers whose work he visualized, and with fellow illustrators such as Frederic Leighton, George John Pinwell, and Arthur Boyd Houghton, all contributing to the vibrant graphic arts scene of the 1860s. The technical demands of his designs also fostered close working relationships with the leading wood engraving firms, particularly the Dalziel Brothers and Joseph Swain, who translated his intricate drawings into printable blocks.

His sister, Emma Sandys (1843-1877), was also a painter, influenced by both her brother and the Pre-Raphaelite style. She specialized in portraits and medievalist subjects, and there is often a stylistic similarity between their works, sometimes leading to attribution difficulties.

While deeply embedded in the Pre-Raphaelite milieu, Sandys also drew inspiration from earlier art. The influence of Northern Renaissance masters like Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein can be seen in his precise linearity and detailed rendering, particularly in his portraits and drawings. This connection to an older tradition of Northern European art distinguishes him somewhat from the more Italianate focus of some Pre-Raphaelites.

Personal Life: Complex Relationships and Financial Struggles

Anthony Frederick Sandys's personal life was complex and, at times, unconventional for the Victorian era. He married Georgiana Creed in Norwich in 1853, but the marriage was not a lasting success. After moving to London, he largely lived apart from his wife, though they never formally divorced.

In the early 1860s, Sandys began a long-term relationship with Keomi Gray, a Romani woman whom he met in Norwich and who became a significant model for him. She appears in paintings such as Keomi and is believed to have inspired the features of figures in works like Medea. Sandys and Keomi Gray had several children together. This relationship, crossing class and cultural boundaries, was characteristic of the bohemian aspects of the artistic world in which Sandys moved.

Later, around 1867, Sandys formed a lasting relationship with the actress Mary Emma Jones, also known as Miss Clive. She became his common-law wife and remained his companion for the rest of his life, bearing him a number of children (many of whom became artists themselves, adopting the surname Sandys). Mary Emma Jones frequently served as his model, appearing in numerous portraits and subject pictures, including, it is believed, the iconic Mary Magdalene (c. 1858-60).

Despite his artistic talents and connections, Sandys often faced financial difficulties. His meticulous, time-consuming method of painting meant that his output was relatively small, and he was not always adept at managing his finances or securing consistent patronage. He sometimes relied on the support of friends and patrons, such as the banker James Anderson Rose and the publisher Alexander Macmillan. His financial instability was a recurring theme throughout his career, leading to periods of hardship. He was also known for his somewhat difficult and proud temperament, which may have hindered some professional relationships.

Controversies and Anecdotes

Sandys's career was not without its share of controversies and notable anecdotes. The aforementioned satirical print The Nightmare (1857), which parodied Millais's Sir Isumbras at the Ford by depicting Millais himself as the knight, Rossetti and Hunt as the children, and a donkey branded "J.R." (for John Ruskin) as the horse, was a bold move for a young artist. While it brought him to the attention of the Pre-Raphaelites, it also demonstrated his sharp wit and capacity for biting satire.

A more serious controversy arose concerning his painting Mary Magdalene (c. 1858-60). This striking depiction of the penitent saint, her face pressed against a patterned damask background, bore a resemblance to some of Rossetti's contemporary works featuring similar compositions and intense female figures. Rossetti reportedly accused Sandys of plagiarism, leading to a temporary cooling of their friendship. However, art historians have noted that Sandys's version is distinct in its harder, more precise execution, and some have even suggested that Rossetti may have later borrowed elements from Sandys. The exact nature of the artistic exchange and influence remains a subject of discussion.

His relationship with Keomi Gray was also a source of fascination and perhaps some scandal in Victorian society, given the prevailing attitudes towards Romani people and unconventional relationships. Her striking, "exotic" appearance made her a compelling model for Sandys and other artists interested in non-traditional forms of beauty.

Sandys's decision to leave his wife in Norwich and establish new relationships in London, while not uncommon in bohemian artistic circles, would have been viewed critically by conventional Victorian society. His personal life, marked by these complex domestic arrangements, contributed to his somewhat enigmatic reputation.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In his later career, Sandys continued to produce portraits, particularly chalk drawings, which provided a more consistent source of income than his elaborate oil paintings. He remained committed to his high standards of craftsmanship, even as artistic tastes began to shift towards Impressionism and other modern movements. He was one of the founding members of the International Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Gravers in 1898, an organization that sought to promote a broader range of artistic styles than those typically favored by the Royal Academy.

Despite his undeniable talent, Sandys never achieved the widespread fame or financial security of some of his Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries like Millais or Hunt, or later figures like Frederic Leighton or Lawrence Alma-Tadema. His relatively small output, his sometimes difficult personality, and his unwavering commitment to a highly finished, detailed style may have contributed to this.

Anthony Frederick Sandys died in Kensington, London, on June 25, 1904. While he may have been somewhat overlooked in the decades immediately following his death, there has been a renewed appreciation for his work in more recent times, particularly as part of the broader reassessment of Victorian art.

His legacy rests on his exceptional draughtsmanship, his powerful and psychologically acute portrayals of women, and his significant contributions to the art of wood engraving. His paintings, with their jewel-like colors, meticulous detail, and intense emotional charge, stand as unique achievements within the Pre-Raphaelite orbit. He explored the darker, more unsettling aspects of human nature and mythology, creating images that continue to fascinate and disturb. Artists like Aubrey Beardsley, with his own incisive line and decadent themes, can be seen as inheritors of a certain strand of Sandys's artistic sensibility.

Conclusion: The Uncompromising Vision of a Victorian Master

Anthony Frederick Sandys was an artist of uncompromising vision and extraordinary technical skill. Rooted in the traditions of the Norwich School and profoundly shaped by his association with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he forged a distinctive artistic identity. His meticulous attention to detail, his intense and often unsettling portrayals of female figures, and his mastery of various media, from oil painting to chalk portraiture and wood engraving, mark him as a significant figure in nineteenth-century British art.

While his personal life was complex and his career marked by periods of financial struggle, Sandys remained dedicated to his artistic principles. His works, characterized by their precision, psychological depth, and often dramatic intensity, offer a compelling glimpse into the Victorian imagination. Today, his paintings and drawings are prized for their exquisite craftsmanship and their powerful exploration of myth, literature, and the human psyche, securing Anthony Frederick Sandys a distinguished and enduring place in the annals of art history. His influence, though perhaps not as widely broadcast as some of his peers like James McNeill Whistler or Edward Burne-Jones, is undeniable for those who appreciate the potent combination of technical brilliance and profound emotional content.