Georg Pauli (1855-1935) stands as a significant and complex figure in the landscape of Swedish art history. Primarily known as a painter, particularly for his monumental frescoes and engagement with modern styles, Pauli was also a prolific writer, an influential cultural critic, an art theorist, and an active participant in the architectural and cultural policy debates of his time. His long and productive career spanned a period of dramatic artistic change, from the dominance of Naturalism in his youth to the rise of Modernism, a movement he both embraced and critiqued. His multifaceted contributions, diverse artistic output, and outspoken personality left an indelible mark on the cultural life of Sweden.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Georg Vilhelm Pauli was born on July 2, 1855, in Jönköping, Sweden, into a family with Italian roots. His initial artistic inclinations led him to Stockholm, where he enrolled at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts (Konstakademien) in the 1870s. This period provided him with a foundational academic training, but like many aspiring artists of his generation, Pauli felt the pull of continental Europe, particularly Paris, which was then the undisputed center of the art world.

Between the late 1870s and the mid-1880s, Pauli undertook crucial study trips abroad, spending significant time in France and Italy. These journeys were formative. In Paris, he was exposed to the latest artistic currents. He was particularly influenced by the French Naturalist painter Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose emphasis on objective representation, meticulous detail, and painting en plein air (outdoors) resonated with many young artists seeking an alternative to staid academic conventions. This influence is visible in Pauli's earlier works, which often featured realistic depictions of landscapes and everyday life, rendered with sensitivity to light and atmosphere.

His time in Italy further broadened his artistic horizons, exposing him to the masters of the Renaissance and the rich tradition of mural painting. This experience likely planted the seeds for his later interest in monumental art and decoration, distinguishing him from many contemporaries who focused solely on easel painting. These early travels were not just about technical learning; they immersed Pauli in international artistic dialogues and helped shape his cosmopolitan outlook.

Evolution of Artistic Style: From Naturalism to Modernism

Georg Pauli's artistic journey was marked by a willingness to experiment and adapt, resulting in a diverse body of work that defies easy categorization. While his early career was rooted in the Naturalism learned in Stockholm and France, he did not remain static. The late 19th century saw the rise of Symbolism and Synthetism, movements that prioritized subjective experience, emotion, and simplified forms over strict realism. Artists like Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard were pioneering these ideas in France. While Pauli may not have fully adopted their style, the shift towards greater expressiveness and decorative qualities can be observed in his work as the century turned.

A defining characteristic of Pauli's mature style was his engagement with monumental painting and mural work. He became one of Sweden's foremost fresco painters, undertaking numerous public commissions. This required a different approach than easel painting – demanding simplification of form, clarity of composition, and an understanding of architectural space. His work in this area often blended historical or allegorical themes with a modern sensibility.

Perhaps most notably, Pauli engaged with Cubism in the early 20th century. Unlike the analytical deconstruction practiced by Pablo Picasso or Georges Braque, Pauli's interpretation was more decorative and synthetic. He was particularly drawn to the structured compositions and geometric forms associated with artists like André Lhote and Jean Metzinger, French Cubists with whom he had personal contact and whose works he collected. Pauli integrated Cubist principles – faceted planes, flattened perspectives – into fundamentally figurative compositions, creating a unique and sometimes controversial hybrid style. His use of color remained vibrant, often employing bold contrasts to enhance the decorative effect.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Georg Pauli's oeuvre includes portraits, landscapes, genre scenes, and, significantly, large-scale decorative works. Several pieces stand out as representative of his artistic concerns and stylistic evolution.

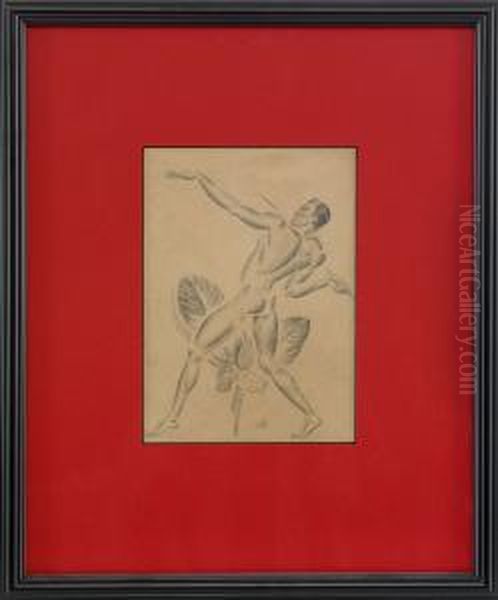

Badande ynglingar (Bathing Youths), completed around 1914, is a notable example of his interest in mythological or archetypal themes, rendered in his distinctive modern style. The work likely depicts figures inspired by Nordic folklore or classical antiquity, set within a stylized natural landscape. The treatment of the figures often shows the influence of his engagement with Cubism, with simplified forms and a focus on rhythmic composition. The contrast between the youthful figures and their environment explores themes of nature, vitality, and perhaps a connection to a timeless, mythical past.

Another significant work often cited is Mens Sana in Corpore Sano (A Healthy Mind in a Healthy Body). This title, derived from the Roman poet Juvenal, points to Pauli's interest in classical ideals, but the execution reflects his modern artistic language. Such works often featured robust, idealized figures engaged in activities suggesting physical and spiritual well-being, composed using the geometric simplifications and structured arrangements influenced by Cubism. It exemplifies his effort to synthesize classical humanism with modern artistic forms.

His work on the Flames series, though less specifically documented in the provided context, likely explored dynamic, perhaps symbolic themes through powerful compositions and color. Fire and flame are potent symbols of energy, transformation, passion, or destruction, suggesting these works might have carried significant allegorical weight, executed in his characteristically vigorous style.

Beyond these specific examples, Pauli was a sought-after portrait painter, capturing the likenesses of prominent figures of his time. His landscapes, particularly from his earlier period, show his skill in capturing the nuances of the Swedish environment. Throughout his work, a recurring interest in the human figure, narrative potential, and the decorative integration of art into its surroundings is evident.

The Muralist and Public Artist

Georg Pauli's commitment to monumental painting set him apart in the Swedish art scene. He believed strongly in the social role of art and saw murals as a way to bring art into public spaces, making it accessible beyond the confines of galleries and private collections. This aligned with a broader European trend around the turn of the century, where artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes in France revived large-scale decorative painting for public buildings.

Pauli executed numerous significant mural commissions throughout Sweden. He created frescoes for schools, libraries, and other public institutions. For instance, starting in 1911, he was involved in designing and decorating school buildings in his hometown of Jönköping. He also undertook important decorative projects in Gothenburg, having been invited by the city's reconstruction committee in 1910. His murals often depicted historical events, allegorical scenes, or representations of local life and industry, tailored to the function of the building and the community it served.

His approach to mural painting was characterized by a strong sense of design, often incorporating simplified forms and bold outlines suitable for viewing from a distance. He experimented with different techniques, including fresco, which requires painting on wet plaster. This demanding medium suited his interest in creating durable works integrated with the architecture itself. His efforts in this field contributed significantly to the revival of mural painting in Sweden and underscored his belief in art's public and didactic potential.

Pauli as Writer, Critic, and Cultural Debater

Georg Pauli's influence extended far beyond his painterly practice. He was an active and often provocative voice in Swedish cultural life, wielding his pen as effectively as his brush. He authored several books and numerous articles on art, artists, and cultural policy, engaging directly with the pressing issues of his time.

His book Konstnärslif och om konst (Artist's Life and About Art) provides insights into his views on the creative process, the role of the artist in society, and his observations on the art world. His writing style was often characterized by a blend of serious theoretical reflection and sharp, sometimes humorous or satirical, commentary. He wasn't afraid to express strong opinions or challenge established norms. For example, his commentary on Swedish coffee culture, using the slang term "barbariskt," served as a vehicle for broader social critique, demonstrating his use of everyday observations for pointed commentary.

Pauli was deeply involved in cultural politics. He advocated for reforms aimed at making art more accessible and integrated into society. His proposals included ideas for a "Modern Museum Plan," which envisioned museums not just as repositories of artifacts but as dynamic educational institutions. He argued for a "socialization" of art education, suggesting that art should play a more central role in public life and civic development. His calls for artists to address social needs and even resource scarcity reflect a pragmatic, socially engaged perspective.

His critiques could be pointed. He expressed opinions on the Parisian art scene and had a complex, sometimes critical, stance towards aspects of Modernism, such as certain manifestations of Cubism, even as he incorporated elements of it into his own work. These activities made him a central, if sometimes controversial, figure in Swedish cultural debates, stimulating discussion and pushing for change. His extensive correspondence further reveals his active engagement with the cultural network of his time.

Artistic Network and Collaborations

Throughout his long career, Georg Pauli cultivated a wide network of relationships within the Swedish and international art worlds. His studies abroad, his active participation in artists' organizations, and his role as a cultural commentator placed him at the center of many artistic dialogues.

In Sweden, he was a member of the Konstnärsföreningen (Artists' Association) and was associated with the Opponenterna (The Opponents), a group of artists who reacted against the conservative practices of the Royal Academy in the 1880s. This group included prominent figures like Richard Bergh, who also became known for his national romantic paintings and portraits. Pauli's relationship with these contemporaries was complex, involving both collaboration and, at times, artistic or ideological differences.

His most significant personal and artistic relationship was with his wife, Hanna Hirsch-Pauli (1864-1940). Also a successful painter, Hanna was known for her intimate portraits and genre scenes, often influenced by French Naturalism and plein air painting. Her famous work Frukostdags (Breakfast Time, 1887) is a masterpiece of Swedish Naturalism. Georg and Hanna formed a prominent artistic couple, supporting each other's careers, occasionally exhibiting together, and hosting gatherings at their home, Villa Pauli, which became a meeting place for Stockholm's cultural elite. Georg publicly expressed admiration for his wife's artistic achievements. They sometimes collaborated on projects, such as decorative schemes, reflecting their shared artistic life.

Pauli's international connections remained important throughout his career. His early admiration for Jules Bastien-Lepage shaped his formative years. His later engagement with Cubism brought him into contact with French artists like André Lhote and Jean Metzinger. He also maintained an awareness of and respect for older masters, citing influences like the Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix and the Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, indicating a broad appreciation of art history that informed his own eclectic practice. He likely interacted with or was aware of other leading Swedish artists of his time, such as Anders Zorn and Carl Larsson, though their artistic paths often diverged from his more modernist and monumental inclinations. His engagement with younger modernists, like Isaac Grünewald, might have been more critical, given Pauli's complex stance on the evolution of modern art.

Controversies and Critical Reception

Georg Pauli's strong personality and outspoken views inevitably led to controversy. His sharp critiques, published writings, and radical proposals for cultural reform often sparked debate within the Swedish art establishment and broader society.

His engagement with Cubism was itself a point of discussion. While he adopted elements of the style, particularly in his monumental works, his approach was distinct from the more radical experiments happening in Paris. Some critics may have found his blend of Cubist geometry with figurative representation inconsistent or overly decorative. His own written critiques of certain aspects of modern art, including Cubism, further highlighted his complex and sometimes ambivalent relationship with the avant-garde. He seemed to value structure and modernity but perhaps resisted what he saw as the excesses of abstraction or deconstruction.

His proposals for cultural policy, such as the "socialization" of art education and his vision for museums as active educational centers, were forward-thinking but likely challenged traditional views on the role of art and cultural institutions. His calls for artists to be more socially responsible and pragmatic could also have been contentious in a milieu where artistic autonomy (l'art pour l'art) was a powerful ideal.

The humor and satire in his writings, while making his work engaging, could also be perceived as biting or overly critical. His willingness to tackle sensitive issues head-on ensured that he remained a figure who provoked strong reactions, both positive and negative. However, this very public engagement also cemented his position as a significant cultural commentator whose opinions carried weight.

Personal Life: The Pauli Partnership

Georg Pauli's personal life was deeply intertwined with his artistic career, particularly through his marriage to Hanna Hirsch in 1887. Their union was more than a personal bond; it was an artistic partnership that lasted over five decades. Both were established artists before their marriage, and they continued to pursue their individual careers while sharing a life dedicated to art.

Hanna Pauli achieved considerable recognition for her sensitive portraits, especially of children and friends, and her depictions of domestic life, often painted with a bright palette and a keen sense of observation influenced by French Naturalism and Impressionism. Georg and Hanna maintained separate studios but shared a vibrant intellectual and social life. Their home, Villa Pauli, designed in the early 20th century, was not just a residence but a statement, reflecting their artistic tastes and serving as a hub for artists, writers, and intellectuals.

Their mutual support was evident. Georg organized exhibitions that included Hanna's work, and he openly praised her talent. While their artistic styles differed – Hanna remained closer to Naturalism and intimate subjects, while Georg pursued monumental painting and modernist experimentation – they shared a deep commitment to their craft. Their partnership represents a fascinating example of two successful artists navigating careers and family life within the cultural landscape of their time. They had three children together, further grounding their lives amidst their intense artistic activities.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Georg Pauli remained active as an artist and writer well into the 20th century. He continued to undertake commissions, exhibit his work, and participate in cultural discourse. His later works maintained his characteristic blend of figurative representation with modernist stylization, particularly in his murals. He passed away on November 28, 1935, in Stockholm, leaving behind a substantial and varied body of work and a legacy as one of Sweden's most dynamic cultural figures of his era.

Pauli's influence is multifaceted. As a painter, he is remembered for his pioneering work in modern mural painting in Sweden and for his unique synthesis of Cubist principles with figurative traditions. His large-scale public works integrated art into the social fabric in a way that few other Swedish artists of his generation achieved. Works like Badande ynglingar and Mens Sana in Corpore Sano remain important examples of Swedish modernism.

As a writer and critic, his contributions stimulated debate and helped shape cultural policy. His ideas about the social role of art, the function of museums, and the importance of art education were progressive for their time and continue to resonate. His writings offer valuable insights into the artistic climate of late 19th and early 20th century Sweden.

His role as a networker and cultural mediator, connecting Swedish artists with international trends and fostering dialogue through his writings and social engagement, was also crucial. He and Hanna Pauli together formed a significant node in the cultural life of Stockholm.

While his eclectic style and sometimes controversial stances meant that his reception was not always uniformly positive during his lifetime, Georg Pauli is now recognized as a major figure who navigated the complex transition from 19th-century traditions to 20th-century modernism with intellectual rigor and artistic boldness. His works are held in major Swedish collections, including the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, ensuring his continued visibility.

Conclusion

Georg Pauli was far more than just a painter. He was an artist-intellectual, a muralist, a theorist, a critic, and a cultural force. His career reflects the turbulent and exciting transformations in European art from the 1870s to the 1930s. He absorbed influences from Naturalism, Symbolism, and Cubism, forging a distinctive style, particularly evident in his monumental works. His commitment to public art, his provocative writings, and his active engagement in cultural policy debates demonstrate his belief in art's power to shape society. Alongside his wife, Hanna Pauli, he occupied a central place in Swedish cultural life for decades. Georg Pauli's enduring legacy lies in his diverse artistic production, his intellectual contributions, and his unwavering commitment to the vitality and social relevance of art.