John Mix Stanley stands as a pivotal yet often underappreciated figure in the grand narrative of 19th-century American art. An intrepid explorer, a meticulous observer, and a gifted painter, Stanley dedicated much of his life to documenting the landscapes, peoples, and cultures of the American West during a period of profound transformation. His work offers a vital window into a world that was rapidly changing, capturing the majesty of the frontier and the dignity of its Native American inhabitants with a sensitivity that was both of its time and, in many ways, ahead of it. Despite catastrophic losses of his work to fire, the surviving pieces and historical records affirm his place as a significant chronicler of American expansion and a key artist of the Western genre.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Born on January 17, 1814, in Canandaigua, New York, John Mix Stanley's early life was marked by an environment that inadvertently sowed the seeds for his future artistic endeavors. His father's tavern was a meeting place for a diverse array of individuals, including local Native Americans and pioneers heading westward. These early encounters likely sparked a nascent fascination with Indigenous cultures and the unfolding drama of the frontier. This formative period, however, was also touched by hardship. Stanley was orphaned in 1828 at the tender age of fourteen.

Following this loss, Stanley was apprenticed to a coach maker, where he began to learn the rudiments of painting, likely starting with decorative work. His ambition, however, extended beyond purely functional artistry. By 1834, he had relocated to Detroit, Michigan, a bustling gateway to the West. There, he initially worked as a house and sign painter, common entry points for aspiring artists of the era. It was in Detroit that he encountered James Bowman, an itinerant portrait painter who had received some training in Europe. Under Bowman's tutelage, Stanley honed his skills in portraiture, a genre that would remain central to his work throughout his career. This period was crucial in transitioning him from a trade painter to a professional artist with loftier aspirations.

The Lure of the West: Initial Forays and Portraits

The 1830s and early 1840s saw Stanley establishing himself as a portrait painter, traveling through Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin. His skills grew, and so did his reputation. However, the true call of his artistic spirit lay further west, in the lands largely uncharted by American artists. In 1839, he painted portraits at Fort Snelling in present-day Minnesota, a key outpost on the edge of the frontier. This experience brought him into closer contact with various Native American tribes, including the Sioux (Dakota).

It was in 1842 that Stanley made a decisive move, venturing into the "Indian Territory" (present-day Oklahoma and surrounding areas). He spent several years traveling among different tribes, including the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, and Osage. During this period, he immersed himself in their cultures, sketching and painting numerous portraits and scenes of daily life. His approach was one of keen observation, aiming to create an accurate visual record. He, like his contemporary George Catlin, recognized the profound cultural shifts occurring as westward expansion intensified and sought to document these peoples before their traditional ways of life were irrevocably altered. Catlin had already spent years traveling the West, creating his famous "Indian Gallery," and Stanley was undoubtedly aware of his predecessor's efforts, perhaps even inspired by them.

Documenting a Nation in Flux: Major Expeditions

Stanley's reputation as a skilled artist capable of enduring the rigors of frontier travel led to his involvement in several significant government-sponsored expeditions. These expeditions were crucial for his career, providing him with unparalleled access to remote regions and diverse Indigenous groups, as well as official patronage.

In 1846, at the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, Stanley joined Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny's "Army of the West" as its official topographical draftsman and artist. The expedition marched from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, through present-day New Mexico and Arizona, to California. Stanley's role was to document the terrain, military engagements, and local populations. His sketches and paintings from this period, such as views of Santa Fe and depictions of Pueblo peoples, provided valuable visual information. He also contributed illustrations to Lieutenant William H. Emory's influential report, "Notes of a Military Reconnoissance," published in 1848, which brought his work to a wider audience. Artists like Seth Eastman, a military officer himself, also contributed significantly to the visual record of Native American life through official channels, creating a parallel body of work.

Following his service with Kearny, Stanley continued his Western explorations. He traveled through Oregon Territory, further expanding his portfolio of landscapes and Native American portraits. His experiences during these years were foundational, providing him with a vast repository of sketches and memories that would inform his studio paintings for years to come.

A Pacific Interlude: Hawaii

In a fascinating detour from his focus on the American West, Stanley traveled to the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1848. He spent approximately a year in the islands, a period during which he became a favored portraitist of the Hawaiian royalty. He painted portraits of King Kamehameha III, Queen Kalama, and other members of the aliʻi (nobility). These works, such as his regal depiction of Prince Lot Kamehameha, demonstrate his skill in capturing likeness and conveying status, adapting his style to a different cultural context. His Hawaiian sojourn added another unique dimension to his already diverse body of work, setting him apart from many of his contemporaries who focused solely on the continental United States. This international experience, though brief, broadened his artistic horizons.

The Grand Vision: The Indian Gallery

Upon his return to the eastern United States in the early 1850s, Stanley embarked on his most ambitious project: the creation of a comprehensive "Indian Gallery." He envisioned a collection of paintings that would serve as a lasting monument to the Native American peoples he had encountered. He established a studio in Washington, D.C., and began producing large-scale canvases based on his field sketches and experiences.

In 1852, Stanley exhibited his Indian Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution. The collection comprised over 150 paintings, primarily portraits, but also including scenes of tribal life, ceremonies, and landscapes. It was a remarkable achievement, rivaling George Catlin's earlier gallery in scope and ambition. Stanley hoped that the U.S. government would purchase his collection for the nation, preserving it as an invaluable historical and artistic record. He, like Catlin before him and Charles Bird King, whose Native American portraits were also housed at the Smithsonian, believed deeply in the ethnographic importance of his work. He saw his art as a means of preserving the memory of cultures he believed were "vanishing."

His gallery included powerful works such as Osage Scalp Dance (1845), a dramatic and meticulously detailed depiction of a tribal ceremony, and numerous individual portraits that conveyed the dignity and character of his sitters. These paintings were not mere ethnographic studies; they were also accomplished works of art, demonstrating Stanley's skill in composition, color, and characterization.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

John Mix Stanley's artistic style evolved throughout his career but generally adhered to the prevailing tenets of 19th-century American realism, often infused with a romantic sensibility. His early portraits show the influence of painters like James Bowman, with a focus on clear likeness and solid modeling. As he ventured west, his style adapted to the demands of landscape and narrative scenes.

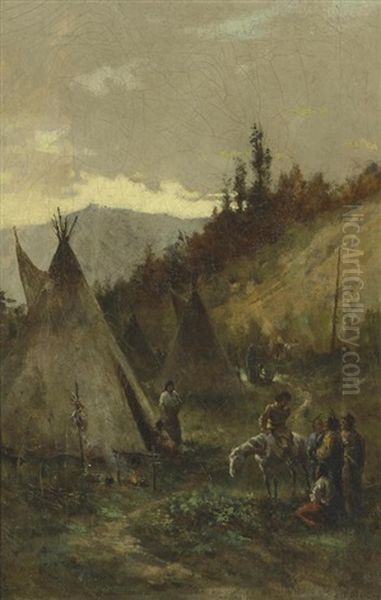

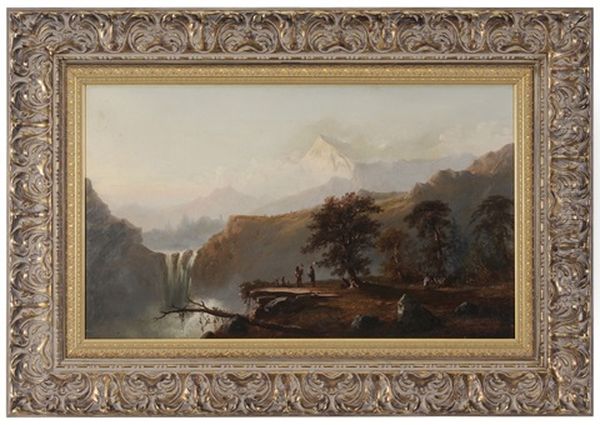

His landscapes, such as Mountain Landscape with Indians (also known as Scene on the Columbia River, Mount Hood in the Distance), reveal an appreciation for the grandeur of the American wilderness, akin in spirit, if not always in technique, to some Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole or Asher B. Durand, though Stanley's focus was distinctly Western. He was adept at capturing atmospheric effects and the play of light, qualities that sometimes approached the Luminist tendencies seen in the work of artists like Sanford Robinson Gifford or John Frederick Kensett.

In his depictions of Native Americans, Stanley aimed for accuracy in dress, accoutrements, and custom. Works like The Trappers show a keen eye for detail, depicting figures with a blend of European and Indigenous attire, reflecting the cultural amalgamation of the frontier. However, his work also engaged with the prevalent 19th-century ideologies concerning Native Americans. The theme of the "vanishing race" is evident in paintings like The Last of Their Race (1857). This monumental canvas, depicting a small group of Native Americans gazing out at the Pacific Ocean, is imbued with a sense of melancholy and impending loss, a common trope in the art and literature of the period, also explored by sculptors like Thomas Crawford in works such as "The Dying Chief Contemplating the Progress of Civilization."

Stanley's participation in government expeditions also meant his work sometimes served the agenda of westward expansion, or "Manifest Destiny." His illustrations for official reports helped to map and visualize the West for an American public eager for information about these new territories. Yet, within this framework, his individual portraits often convey a deep respect for his subjects, transcending simple ethnographic documentation. He was, in this sense, a complex figure, an artist working within the cultural currents of his time while also forging a unique personal vision.

The Stevens Pacific Railroad Survey

One of Stanley's most significant contributions came through his involvement with the Pacific Railroad Surveys. In 1853, he was appointed chief artist for Isaac I. Stevens's northern route survey, which aimed to find a practical railway path from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Puget Sound in Washington Territory. This was an arduous and extensive expedition, covering vast and often challenging terrain.

During the Stevens expedition, Stanley produced a remarkable body of work, including numerous sketches and paintings of landscapes, geological formations, and encounters with various Native American tribes, such as the Blackfoot, Gros Ventre, and Salish. His detailed images, like Chain of Spires along the Gila River (from an earlier expedition but indicative of his survey work's style) or depictions of specific mountain passes, were not only artistically valuable but also provided crucial visual data for the survey reports. Many of his illustrations were later reproduced as lithographs and chromolithographs in the official government publications, widely disseminating his vision of the West. This work placed him alongside other artists contributing to the Pacific Railroad Surveys, such as John Charles Frémont's cartographer Charles Preuss, or later artists like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran, who would also paint the West, often with a more overtly romantic and monumental vision.

Masterworks and Signature Pieces

While much of Stanley's oeuvre was tragically lost, the surviving works and reproductions allow us to appreciate his artistic achievements.

Osage Scalp Dance (1845): One of his most famous early works, this painting is a dynamic and detailed portrayal of a significant Osage ceremony. It showcases his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and capture the energy of a cultural event. The meticulous rendering of costumes and actions reflects his commitment to ethnographic accuracy.

The Last of Their Race (1857): Perhaps his most iconic painting, this large canvas depicts a group of Native Americans on a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean at sunset. It is a poignant and symbolic representation of the "vanishing Indian" theme, resonating with contemporary anxieties and sentiments about the fate of Indigenous peoples in the face of American expansion.

The Trappers (circa 1850s-1860s): This painting, also known as The Disputed Shot or Gambling for the Buck, depicts a group of trappers, likely of mixed heritage, in a moment of quiet tension or discussion around a campfire. It captures the rugged individualism and multicultural interactions characteristic of frontier life.

Mountain Landscape with Indians (Scene on the Columbia River, Mount Hood in the Distance): This work exemplifies his skill in landscape painting, combining a majestic natural setting with figures that are integrated into the environment. It is believed to be a rare depiction of a traditional Chinookan plank house village.

Blackfoot Card Players (circa 1850s): This genre scene offers an intimate glimpse into the leisure activities within a Blackfoot lodge, showcasing Stanley's ability to capture everyday moments with sensitivity and detail.

Portraits from the Hawaiian Royalty (1848-1849): His portraits of King Kamehameha III and other Hawaiian nobles are significant for their historical value and artistic quality, demonstrating his versatility as a portraitist.

These works, among others, highlight Stanley's diverse talents, from grand historical and allegorical compositions to intimate portraits and detailed genre scenes.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Heartbreak

Stanley actively sought to bring his work before the public. His 1846 exhibitions in Cincinnati and Louisville, featuring 85 paintings, were early efforts to establish his reputation. The crowning achievement, however, was the installation of his Indian Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution in 1852. This was a significant recognition of his work's importance. He, like many artists of his time, including painters such as Emanuel Leutze, who was known for his historical scenes, understood the power of public exhibition.

Despite the critical acclaim his gallery received, Stanley faced financial difficulties. He lobbied for years for the U.S. Congress to purchase his collection, but these efforts were ultimately unsuccessful. This was a profound disappointment for the artist, who had invested so much of his life and resources into creating this comprehensive visual record.

The greatest tragedy, however, was yet to come. In January 1865, a devastating fire swept through the Smithsonian Castle, destroying the majority of Stanley's Indian Gallery – over 200 paintings. Only a handful of works that were on loan or stored elsewhere survived. Later that same year, another fire at P.T. Barnum's American Museum in New York, where Stanley had some other paintings on display, consumed more of his life's work. These fires were a catastrophic blow, wiping out a significant portion of America's visual heritage of Native American life and a substantial part of Stanley's artistic legacy. The loss is comparable in its cultural impact to the potential loss of works by naturalists like John James Audubon, whose detailed renderings of American birdlife were also crucial documents of their time.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

John Mix Stanley operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic landscape. His most direct contemporary in the field of Native American portraiture was George Catlin. Both artists shared a mission to document Indigenous cultures, and there was an implicit rivalry between them, though Stanley's later work often displayed a more refined academic technique. Karl Bodmer, a Swiss artist who accompanied Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied up the Missouri River in the 1830s, produced exceptionally detailed and scientifically accurate depictions of Native Americans, setting a high bar for ethnographic illustration. Alfred Jacob Miller, another contemporary, painted the fur trade and Native American life in the Rocky Mountains with a more romantic and painterly style.

In the broader context of American art, Stanley's landscapes can be seen in relation to the Hudson River School, though his subject matter was geographically distinct. Artists like Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt, who came to prominence slightly later, would take the depiction of grand American (and South American) scenery to new heights of scale and drama, often overshadowing earlier Western artists. Seth Eastman, a career army officer, also created a significant body of work depicting Native American life, often with a directness born of his military experience. Charles Bird King had earlier painted numerous portraits of Native American delegates in Washington, D.C., many of which were also tragically lost in the Smithsonian fire. Paul Kane, a Canadian artist, undertook similar journeys to document the Indigenous peoples of Canada and the Pacific Northwest, his efforts paralleling Stanley's in many respects. Stanley's work, therefore, should be understood as part of a broader international effort to document Indigenous cultures during a period of intense colonial expansion.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Devastated by the loss of his paintings, Stanley's output understandably diminished in his later years. He had settled in Detroit in 1864. In 1868, he traveled to Germany, possibly to oversee the creation of lithographs from his surviving sketches or to explore new artistic avenues. He continued to paint, but the grand ambition of his Indian Gallery was irrevocably shattered.

John Mix Stanley passed away in Detroit on April 10, 1872, at the age of 58. Despite the fires, his contributions were not entirely erased. His illustrations for government reports, the few surviving original paintings, and contemporary accounts of his work ensure his place in American art history. He was instrumental in helping to found the Detroit Art Association, which later evolved into the Detroit Institute of Arts, demonstrating his commitment to fostering art in his adopted city.

Today, John Mix Stanley is recognized as one of the most important painters of the American West and Native American life in the mid-19th century. His work provides invaluable historical and ethnographic insights, capturing a pivotal moment in American history. While the scale of his lost gallery can only be imagined, the surviving evidence speaks to an artist of considerable talent, dedication, and vision. He sought to create a lasting memorial to the Indigenous peoples of North America, and in this, even through the fragments that remain, he achieved a measure of enduring success. His art continues to inform our understanding of the complex encounters and transformations that shaped the American nation.