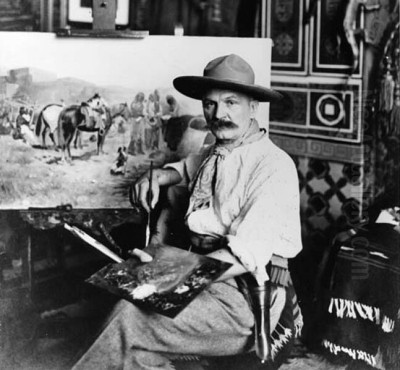

John Hauser (1859-1913) stands as a significant figure in the canon of American art, particularly renowned for his sensitive and detailed portrayals of Native American life and individuals at a time when the traditional cultures of these peoples were undergoing profound and often forced transformations. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, a burgeoning cultural hub in the American Midwest, Hauser developed an early passion for art that would lead him across continents for training and deep into the American West to find his most compelling subjects. His work offers a valuable window into the lives of Native American communities, rendered with a dedication to ethnographic detail and a sympathetic eye, distinguishing him within the broader genre of Western American art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Hauser was born on January 30, 1859, in Cincinnati, Ohio. His early artistic inclinations were nurtured in a city that was, by the mid-19th century, establishing itself as an important center for arts and culture west of the Appalachian Mountains. Cincinnati was home to influential art schools and a growing community of artists. It is likely that Hauser received his initial artistic instruction locally, perhaps at the McMicken School of Design (now the Art Academy of Cincinnati), which was a prominent institution for aspiring artists in the region. This foundational training would have exposed him to the academic traditions prevalent at the time, emphasizing draftsmanship, composition, and the study of form.

Driven by a desire for more advanced and worldly instruction, Hauser, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, sought further education in Europe. He traveled to Munich, Germany, which, alongside Paris, was a leading center for academic art training in the late 19th century. Hauser enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, a school known for its rigorous curriculum and its advocacy of a painterly realism, often characterized by dark palettes, bravura brushwork, and an emphasis on capturing character and psychological depth. Artists like Frank Duveneck and William Merritt Chase, fellow Americans, also famously studied in Munich, and the "Munich School" style had a considerable impact on American art. Hauser's time in Munich, likely in the early 1880s, would have profoundly shaped his technical skills and artistic outlook.

The Journey West: Documenting Native American Life

Upon returning to the United States, Hauser's artistic focus began to crystallize around the depiction of Native American subjects. This was not an uncommon theme in American art of the period; artists like George Catlin and Karl Bodmer had earlier ventured west to document what many believed was a "vanishing race." By Hauser's time, the romanticism associated with the West was coupled with a growing, albeit often paternalistic, ethnographic interest. Hauser, however, approached his subjects with a notable degree of empathy and a commitment to firsthand observation.

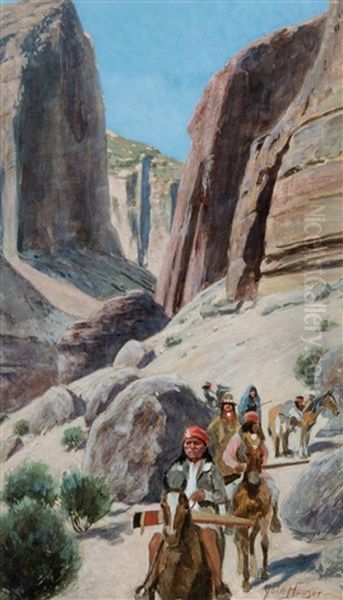

Starting in the late 1880s and continuing for over two decades, Hauser embarked on numerous journeys into the American West and Southwest. He traveled extensively through territories that would become states like Arizona, New Mexico, South Dakota, and Montana. These expeditions were not casual tourist trips; they involved immersing himself in the environments and communities he wished to paint. He spent considerable time among various Native American tribes, including the Sioux (Lakota, Dakota), Apache, Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni. He learned about their customs, observed their daily lives, and sought to build relationships of trust that would allow him to create authentic portraits and genre scenes.

His dedication was such that he reportedly learned some of the Native languages to better communicate with his subjects. He collected artifacts, clothing, and tools, not merely as props for his paintings, but as items of cultural significance that informed his understanding and enriched the accuracy of his depictions. This commitment to authenticity became a hallmark of his work. He established a winter studio in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, and later, in 1901, he and his wife, Minnie, built a home in a Pueblo Revival style in Clifton, Cincinnati, which they named "Pine Ridge" after the Lakota reservation, filling it with his collection of Native American artifacts.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Representative Works

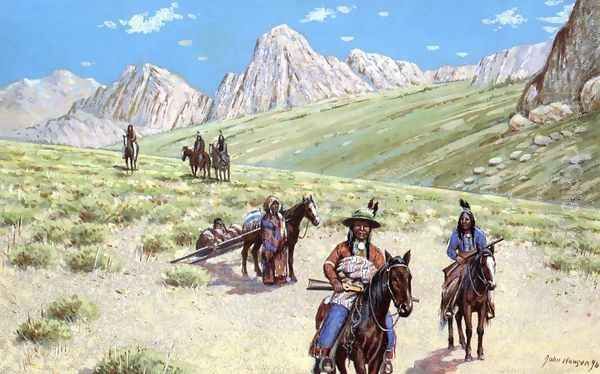

John Hauser's artistic style was rooted in the academic realism he absorbed in Munich, but it evolved to suit his chosen subject matter. His paintings are characterized by careful draftsmanship, a rich and often earthy color palette, and a strong sense of composition. While some of his contemporaries, like Frederic Remington or Charles M. Russell, often focused on the dramatic action and conflict of the "Wild West," Hauser's work frequently conveyed quieter, more intimate moments of Native American life. He painted portraits that captured the dignity and individuality of his sitters, as well as scenes of daily activities, ceremonies, and family life.

His works often feature meticulous attention to the details of clothing, adornment, and traditional dwellings. This ethnographic concern did not, however, overshadow the artistic merit of his paintings. He skillfully used light and shadow to model forms and create atmosphere, and his compositions were thoughtfully arranged to draw the viewer into the scene.

Among his notable works, titles like "Mountain Desert Trail" and "Plains Indians Hunting in Winter Landscape" (as mentioned in the initial query, though specific images and dates for these exact titles can be varied in auction records and collections) are indicative of his thematic concerns. More broadly, his oeuvre includes numerous portraits of chiefs and other individuals, such as "Chief Red Cloud," "Chief American Horse," and "Geronimo," as well as genre scenes depicting camp life, hunting expeditions, and ceremonial dances. For example, a painting titled "Sioux Camp at Pine Ridge" would showcase his ability to combine portraiture with a broader depiction of community life, while a work like "Apache Water Carriers" would highlight daily activities and the relationship between the people and their environment.

Hauser's paintings often convey a sense of dignity and resilience in his subjects, even as they faced immense pressures from westward expansion and government policies. While his perspective was inevitably that of an outsider, his sustained engagement and detailed observation set his work apart. He was less interested in the sensationalism that sometimes characterized Western art and more focused on a respectful representation of cultures he clearly admired.

Hauser in the Context of His Contemporaries

John Hauser worked during a vibrant period for art depicting the American West. He was a contemporary of several artists who also dedicated their careers to similar themes, though often with different stylistic approaches or thematic emphases.

Henry Farny (1847-1916), another Cincinnati-based artist who also studied in Munich, was a close contemporary and shared Hauser's interest in Native American subjects. Farny's work, often in watercolor and gouache, is known for its clarity and detailed realism, and like Hauser, he traveled extensively in the West. Their shared Cincinnati roots and European training provide an interesting parallel.

Joseph Henry Sharp (1859-1953), born the same year as Hauser, was a key figure in the Taos Society of Artists. Sharp was profoundly dedicated to painting Native American portraits and scenes, establishing a studio at Crow Agency in Montana before becoming a central figure in Taos, New Mexico. Like Hauser, Sharp was committed to preserving a visual record of Native American life and individuals. Other members of the Taos Society, such as E. Irving Couse (1866-1936) and Oscar E. Berninghaus (1874-1952), also focused on Pueblo and other Southwestern Native cultures, contributing to a distinct regional school of American art.

Further afield, Frederic Remington (1861-1909) and Charles M. Russell (1864-1926) were perhaps the most famous chroniclers of the American West. Remington, known for his dramatic and action-packed sculptures and paintings of cowboys, soldiers, and Native Americans, often emphasized the conflict and dynamism of the frontier. Russell, the "cowboy artist," provided a more anecdotal and narrative vision of Western life, drawing from his own experiences on the range. While Hauser's work shares the Western setting, its tone is often more ethnographic and less focused on high drama than Remington's or Russell's.

Earlier artists like George Catlin (1796-1872) and Karl Bodmer (1809-1893) had laid the groundwork for the artistic documentation of Native American peoples. Catlin's extensive travels in the 1830s resulted in a vast gallery of portraits and scenes, while Bodmer, accompanying Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied, produced incredibly detailed and sophisticated watercolors of Plains tribes. By Hauser's time, the context had shifted, with the frontier rapidly closing and assimilation policies in full force, lending a different urgency to the work of artists documenting these cultures.

Other artists who explored Native American themes included Charles Bird King (1785-1862), known for his portraits of Native American delegates in Washington D.C., and Seth Eastman (1808-1875), an army officer whose artistic work provided valuable records of Native life. Later, photographers like Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) would also undertake monumental projects to document Native American cultures, often with a romanticized and elegiac tone.

Hauser's connection to the Munich School also links him to other American artists who studied there, such as Frank Duveneck (1848-1919), who became an influential teacher in Cincinnati, and William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), a versatile painter and prominent educator. While these artists did not typically focus on Western subjects, the shared Munich training provided a common artistic language and technical foundation.

Exhibitions and Recognition

John Hauser's work was exhibited during his lifetime and gained recognition for its quality and subject matter. He participated in exhibitions in Cincinnati and other American cities. His paintings were sought after by collectors interested in Western art and Native American culture. The fact that he could sustain a career primarily focused on these subjects speaks to the contemporary interest in his work. He was a member of the Cincinnati Art Club and was respected within the local art community.

While the provided source material seems to conflate John Hauser (1859-1913) with Johann Hauser (1926-1996), an Austrian Art Brut artist, and Arnold Hauser (1892-1978), a Hungarian art historian, it is important to clarify that John Hauser, the American painter of Native Americans, did not have exhibitions at the Gugging Museum, nor did he author texts on the sociology of art or the Renaissance. His contributions were firmly within the realm of American realist painting focused on the West.

The anecdotes mentioned in the source material regarding a cholera outbreak during a Kentucky trip or hardships in Richland County, Illinois, in 1867 (when Hauser would have been only eight years old) are difficult to substantiate for this John Hauser and may pertain to other individuals or are misdated. His documented life focuses on his artistic training and his extensive travels in the West from the late 1880s onwards.

Legacy and Lasting Importance

John Hauser passed away on October 6, 1913, in Cincinnati, Ohio. His death marked the end of a career dedicated to the portrayal of Native American life. His legacy resides in the body of work he left behind – hundreds of paintings that offer a visual record of a critical period in American history. These works are valued not only for their artistic merit but also as historical documents that provide insights into the cultures, appearances, and environments of the Native American peoples he depicted.

His paintings are held in numerous private collections and public institutions, including the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the Woolaroc Museum in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana, among others. These collections preserve his contribution to American art and ensure that his vision of the Native West remains accessible to future generations.

In an era when Native American cultures were often misunderstood, stereotyped, or romanticized, Hauser's approach, while still framed by the perspectives of his time, demonstrated a genuine interest and respect for his subjects. He sought to portray them with dignity and accuracy, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of their lives. His work, when viewed critically and in historical context, continues to be an important resource for art historians, anthropologists, and anyone interested in the complex history of the American West and its original inhabitants. His dedication to traveling to remote locations, living among the people he painted, and striving for authenticity in his representations solidifies his place as a significant chronicler of Native American life at the turn of the 20th century.