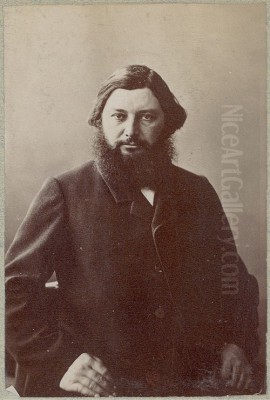

Gustave Courbet stands as a monumental figure in the history of nineteenth-century art, a painter whose commitment to depicting the tangible world fundamentally altered the course of Western painting. Born Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet on June 10, 1819, in the small town of Ornans, near the Jura Mountains in eastern France, and passing away in exile in La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland, on December 31, 1877, his life and career were marked by a fierce independence, a rejection of artistic conventions, and a profound engagement with the social and political realities of his time. He was the chief architect and most vocal proponent of Realism, an artistic movement that sought to portray ordinary life without idealization or romantic embellishment. His work, often controversial and confrontational, challenged the established hierarchies of the art world and paved the way for subsequent modernist movements.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Ornans and Paris

Courbet hailed from a prosperous farming family in the Franche-Comté region. His father, Régis Courbet, was a significant landowner, and the family enjoyed a comfortable status in Ornans. This rural background would deeply inform Courbet's art throughout his life, providing him with subjects rooted in the land and its people. Though his family initially intended for him to study law, Courbet harbored artistic ambitions from a young age. His independent and somewhat rebellious spirit was evident early on.

In 1839, Courbet moved to Paris, ostensibly to pursue legal studies. However, the vibrant artistic atmosphere of the capital quickly captivated him. He abandoned law and dedicated himself to painting, largely teaching himself through rigorous practice and close study of the Old Masters at the Louvre Museum. He was particularly drawn to the Spanish Golden Age painters like Diego Velázquez, whose earthy realism and directness resonated with him, as well as Dutch masters such as Rembrandt van Rijn, admired for his psychological depth and dramatic use of light and shadow. He also studied Venetian painters, absorbing their rich color and textural qualities. Courbet eschewed formal academic training, preferring the independence of working in private studios like that of Charles von Steuben and later, Suisse Académie, which offered models but little formal instruction.

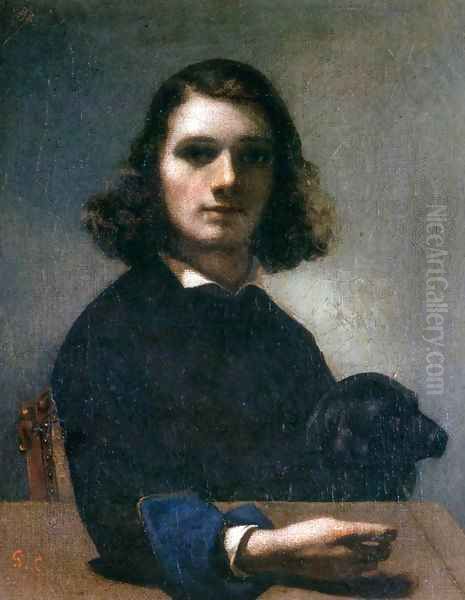

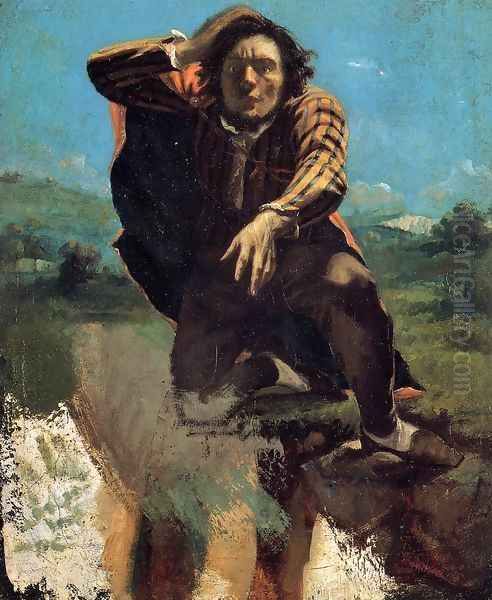

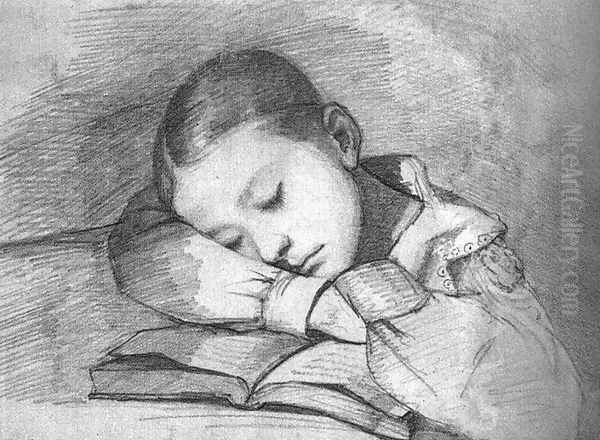

Courbet's early works from the 1840s primarily consisted of literary subjects influenced by Romanticism, portraits of friends and family, and numerous self-portraits. These self-portraits reveal a young artist exploring his identity and artistic persona, often tinged with a Romantic sensibility but already displaying a powerful physical presence and a direct, searching gaze. Notable examples include Self-Portrait with Black Dog (c. 1842-44), where he presents himself stylishly against a landscape backdrop, and the intensely emotional The Desperate Man (c. 1843-45), capturing a moment of artistic angst. Other early works like Portrait of Juliette Courbet (1847), his sister, show his developing skill in capturing likeness and character. Self-Portrait with Leather Belt (1847) and Self-Portrait with Pipe (c. 1848-49) further cemented his image as a confident, somewhat bohemian artist.

The Emergence of Realism: Painting the Truth

By the late 1840s, Courbet began to decisively reject the prevailing artistic trends of Neoclassicism, with its emphasis on historical and mythological subjects and idealized forms (epitomized by artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres), and Romanticism, which favored emotional drama, exoticism, and subjective experience (led by figures such as Eugène Delacroix). Courbet felt that these styles failed to address the realities of contemporary life in France, particularly in the wake of the social upheavals surrounding the 1848 Revolution, which he witnessed firsthand and which fueled his republican sympathies.

Courbet formulated a new artistic doctrine: Realism. He famously declared, "Painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist of the representation of real and existing things. It is a completely physical language." For Courbet, the artist's role was not to beautify or interpret, but to record the observable world with honesty and directness. He believed that art should concern itself with the present, with the experiences of ordinary people, and with the tangible textures of life. He famously stated, "Show me an angel, and I'll paint one," underscoring his rejection of imaginary or historical subjects in favor of contemporary reality.

This commitment led him to turn his attention away from traditional subjects and towards the people and landscapes of his native Ornans. He began depicting peasants, laborers, and the provincial bourgeoisie, subjects previously considered unworthy of serious artistic treatment, especially on the grand scale typically reserved for history painting. His style became bolder, more physical, often employing thick impasto applied with brushes and palette knives, emphasizing the material substance of both the paint and the subjects depicted. This "coarse" or "crude" technique, combined with his unidealized subject matter, quickly set him apart and began to attract controversy.

Monumental Canvases and Salon Controversies

Courbet's breakthrough onto the public stage came with a series of monumental paintings exhibited at the Paris Salon, the official, highly influential art exhibition sponsored by the French state. These works shocked critics and the public alike, challenging established notions of taste, beauty, and appropriate subject matter for high art.

The Stonebreakers (1849), now tragically destroyed during the bombing of Dresden in World War II, depicted two anonymous laborers, a young boy and an old man, engaged in the back-breaking work of breaking rocks for road gravel. Courbet presented them life-sized, with uncompromising realism, highlighting the drudgery and poverty of rural labor without sentimentality or picturesque charm. Critics condemned the painting for its perceived "ugliness" and "vulgarity," finding the subject matter base and the technique rough. Yet, for others, particularly socialists and reformers, the painting was a powerful social statement, an unvarnished look at the harsh realities faced by the working class. Its destruction represents a significant loss for art history, but its impact remains through photographs and contemporary accounts.

Even more controversial was A Burial at Ornans (1849-50), a colossal canvas measuring over ten by twenty feet. It depicted the funeral of Courbet's great-uncle in his hometown, attended by a cross-section of Ornans society – clergy, local dignitaries, men, women, and Courbet's own family members. What scandalized the Parisian art world was not only the mundane, provincial subject matter treated on a scale usually reserved for heroic historical or religious events, but also the stark, unidealized portrayal of the figures. The mourners are shown with individualized, often plain or grief-stricken faces, arranged in a frieze-like composition that lacks traditional hierarchical focus. Critics derided it as a deliberate cultivation of ugliness and a degradation of the grand tradition of history painting. However, the painting cemented Courbet's reputation as the leader of the burgeoning Realist movement, a fearless challenger of academic norms.

In 1855, Courbet submitted another ambitious, large-scale work, The Painter's Studio: A Real Allegory Summarizing Seven Years of my Artistic and Moral Life, to the jury for the Exposition Universelle in Paris. This enigmatic painting depicts Courbet himself at his easel, painting a landscape, flanked by two groups of figures. On the right are his friends, patrons, and intellectual allies – figures like the critic Champfleury and the philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. On the left is a diverse assembly representing "the other world of trivial life": the poor, the exploited, the wealthy, symbolizing the various aspects of society that Courbet drew upon for his art. A nude model stands behind him, often interpreted as representing "Truth" or "Nature," while a young boy looks on admiringly. The jury accepted some of Courbet's other works but rejected The Painter's Studio due to its size and unconventional nature.

Incensed by this rejection, Courbet took a radical and unprecedented step. He withdrew his accepted works from the official exhibition and financed the construction of his own temporary structure near the Exposition Universelle, calling it the "Pavilion of Realism." Here, he displayed The Painter's Studio along with around forty other paintings, accompanied by a manifesto outlining his Realist principles. This act of defiance against the official Salon system was a landmark moment in the history of modern art, asserting the artist's right to exhibit independently and directly engage the public. It foreshadowed later independent exhibitions like the Salon des Refusés of 1863 and the Impressionist exhibitions starting in 1874.

Courbet continued to provoke throughout his career. The Bathers (1853) caused outrage for its depiction of two robust, unidealized female nudes by a stream, seen as lacking the grace and refinement expected of the subject. Perhaps his most notorious work, L'Origine du Monde (The Origin of the World, 1866), is an explicit close-up depiction of female genitalia. Commissioned privately by a Turkish diplomat, it was kept hidden for decades. Its frankness challenged societal taboos and continues to spark debate about art, censorship, eroticism, and the male gaze. These works, alongside others like Young Ladies of the Village (1851) and The Wheat Sifters (1853), consistently demonstrated Courbet's commitment to portraying life, including the human body, with unflinching honesty.

Courbet's Distinctive Style and Technique

Courbet's Realism was not merely about subject matter; it was also deeply embedded in his technique and style. He developed a distinctive approach to painting that emphasized materiality and directness. He often applied paint thickly, using both brushes and palette knives to build up textured surfaces that conveyed the physical substance of objects – the roughness of stone, the density of foliage, the weight of fabric, the fleshiness of the human body. This technique, known as impasto, gave his paintings a tangible presence that contrasted sharply with the smooth, polished finish favored by academic painters.

His color palette was often earthy and somber, dominated by browns, greens, grays, and blacks, reflecting the landscapes and rural life of the Franche-Comté. However, he could also employ vibrant color when the subject demanded it, particularly in his landscapes and seascapes. His compositions were often unconventional, sometimes deliberately awkward or anti-classical, rejecting traditional rules of balance and harmony in favor of arrangements that felt more immediate and true to life. A Burial at Ornans, for example, with its horizontal, non-hierarchical arrangement, defied compositional norms.

Courbet was a prolific landscape painter, finding constant inspiration in the rugged terrain around Ornans – its forests, caves, streams, and rocky outcrops. Works like The Stream of the Puits Noir (various versions) capture the damp, enclosed atmosphere of the region's valleys. He was also a powerful painter of the sea, particularly drawn to the Normandy coast. His seascapes, such as The Wave (c. 1869-70) or The Cliffs at Étretat after the Storm (1870), are not picturesque views but dramatic confrontations with the raw power of nature, often featuring turbulent waters and imposing geological formations. These works significantly influenced the Impressionists, particularly Claude Monet, who also painted at Étretat.

His still lifes and hunting scenes, like After the Hunt (1857) or the later, poignant The Trout (1871), painted while imprisoned, also showcase his ability to render textures and forms with intense realism. The Trout, depicting a hooked fish gasping for air, is often interpreted as a metaphor for the artist's own predicament following his political entanglements.

Political Engagement, the Paris Commune, and Exile

Courbet was more than just an artist; he was a man deeply engaged with the political currents of his time. A staunch republican and socialist, he believed that art had a social role to play. He participated actively in the Revolution of 1848. His most significant political involvement, however, came during the Paris Commune of 1871, the radical socialist government that briefly ruled Paris after France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.

During the Commune, Courbet was elected President of the Federation of Artists, a body aimed at reforming art institutions and protecting cultural heritage. He played a role in safeguarding Paris's museums from potential damage. However, he also became associated with the Commune's decision to dismantle the Vendôme Column, a symbol of Napoleonic imperialism, although his precise level of responsibility remains debated by historians.

When the Commune was brutally suppressed by the French army, Courbet was arrested. He was tried and sentenced to six months in prison and fined 500 francs. More devastatingly, after his release, the newly established Third Republic government decided in 1873 to hold him personally liable for the cost of reconstructing the Vendôme Column, imposing an enormous fine that threatened him with financial ruin.

To escape bankruptcy and potential further imprisonment, Courbet fled France in July 1873, seeking refuge across the border in Switzerland. He settled in La Tour-de-Peilz on the shores of Lake Geneva. He spent the last four years of his life in exile, continuing to paint, primarily landscapes of the Swiss scenery and still lifes. However, his health deteriorated, exacerbated by heavy drinking. Gustave Courbet died on December 31, 1877, at the age of 58, from liver disease, before the first installment of the crippling fine was due.

Enduring Influence and Legacy

Gustave Courbet's impact on the history of art is immense and multifaceted. As the leading figure of Realism, he fundamentally shifted the focus of art towards contemporary life and ordinary subjects. His insistence on painting only what he could see, his rejection of idealization, and his bold, physical technique challenged centuries of artistic tradition.

His defiance of the Salon system and his establishment of the Pavilion of Realism provided a model for artistic independence that inspired subsequent generations. He demonstrated that artists could operate outside official structures and appeal directly to the public. This paved the way for the Salon des Refusés in 1863, which showcased works rejected by the official Salon, including Édouard Manet's controversial Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe. Manet himself, while forging his own path towards modernism, deeply admired Courbet's audacity and his engagement with modern subjects.

The Impressionists, who launched their own independent exhibitions starting in 1874, owed a significant debt to Courbet. His commitment to contemporary subject matter, his direct approach to landscape painting, and his challenge to academic conventions created a climate in which their own innovations could take root. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Auguste Renoir built upon Courbet's foundation, further exploring the effects of light and atmosphere and capturing fleeting moments of modern life, though often with a less overtly political or social edge. The American expatriate James Abbott McNeill Whistler, whose mistress Jo Hiffernan was the model for Courbet's Jo, La Belle Irlandaise (The Beautiful Irish Girl, 1865-66), also navigated the currents between Realism and aestheticism.

Beyond Impressionism, Courbet's influence extended to Post-Impressionism and early Modernism. Paul Cézanne, often called the "father of modern art," profoundly admired Courbet's structural solidity and the way he built form through paint, stating his desire to "make of Impressionism something solid and durable, like the art of the museums," echoing Courbet's own substantiality. Vincent van Gogh was moved by Courbet's depictions of rural labor. Even Pablo Picasso, decades later, engaged with Courbet's legacy, particularly his structural approach to form and his revolutionary spirit. Courbet's focus on the working class and his social critique also resonated with later movements like Social Realism. Some critics, like Clement Greenberg, saw Courbet's emphasis on the flatness of the canvas and the materiality of paint as a crucial step towards modernist abstraction. Artists like Edgar Degas, with his unvarnished depictions of dancers and laundresses, also shared Courbet's interest in the realities of modern urban life.

Today, Gustave Courbet is recognized as one of the most important artists of the 19th century. His major works, such as A Burial at Ornans and The Painter's Studio, are considered masterpieces and are housed in major museums like the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. He remains a compelling figure: a technically brilliant painter, a radical innovator, a social commentator, and a political activist. His insistence that art should confront the realities of its time, however uncomfortable, continues to resonate. He forced the art world to look at the world around it with a new, unflinching honesty, leaving an indelible mark on the trajectory of modern art. His legacy is that of an artist who dared to paint the truth as he saw it, uncompromisingly and powerfully.