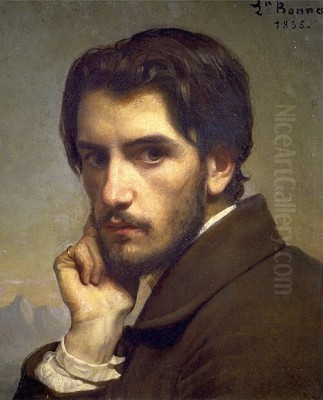

Léon-Joseph Florentin Bonnat stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century French art. Born in Bayonne in 1833, he rose to prominence not only as a highly sought-after portrait painter but also as an influential educator who shaped a generation of artists. His career spanned a period of dramatic change in the art world, yet Bonnat largely remained anchored in a powerful, realistic style deeply indebted to the Spanish masters he admired, carving out a unique niche within the academic tradition while engaging with the burgeoning realism of his time. His legacy is complex, encompassing celebrated portraits, controversial religious works, and a profound impact on the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Léon Bonnat's journey into the world of art began in the southern French town of Bayonne, nestled near the Spanish border. Born into a family where his father operated a bookstore, the young Bonnat was exposed to images and perhaps the lives of artists through print. An early, innate interest in drawing was recognized and encouraged by his father, providing crucial initial support for his artistic inclinations. This familial encouragement set the stage for a more formal pursuit of art when circumstances led the family to relocate.

The pivotal move came when the Bonnat family settled in Madrid, Spain. This relocation proved instrumental in shaping the young artist's aesthetic sensibilities. It was in Madrid that Bonnat received his first formal art training, immersing himself in the rich artistic heritage of Spain. This period laid the foundation for his lifelong admiration of Spanish painting and significantly influenced the direction his own art would take.

The Spanish Influence: Madrazo and the Masters

In Madrid, Bonnat enrolled in the studio of Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz, a prominent Spanish painter known for his portraits and historical scenes, and director of the Prado Museum. Studying under Madrazo provided Bonnat with rigorous academic training, emphasizing draftsmanship and composition. However, perhaps even more impactful was his direct exposure to the masterpieces housed within the Prado.

Bonnat became deeply captivated by the Spanish Baroque masters, particularly Diego Velázquez and Jusepe de Ribera. He spent countless hours studying their techniques, absorbing Velázquez's profound naturalism, subtle command of light, and psychological depth in portraiture. From Ribera, he learned the power of dramatic chiaroscuro (the use of strong contrasts between light and dark), the tactile rendering of surfaces, and an unflinching, often stark realism, especially in religious or Tenebrist subjects. The influence of Francisco Goya, another Spanish giant whose works bridged the Old Masters and modernity, also resonated with Bonnat's developing style. This immersion in Spanish art instilled in him a preference for strong forms, sober palettes often punctuated by rich blacks and earthy tones, and a commitment to representing the tangible reality of his subjects.

Parisian Training and Academic Ascent

Armed with the foundational training and profound influences absorbed in Spain, Bonnat returned to Paris, the undisputed center of the European art world in the mid-nineteenth century. He sought to further refine his skills and establish his career within the highly structured French art system. To this end, he entered the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic tradition.

At the École, Bonnat studied under Léon Cogniet, a respected history and portrait painter himself, and a product of the Neoclassical lineage extending back through Pierre-Narcisse Guérin to Jacques-Louis David. Cogniet's instruction would have reinforced the academic emphasis on precise drawing, historical subjects, and the hierarchy of genres. Bonnat successfully navigated the competitive environment of the École, honing his technical abilities and preparing for his debut at the official Paris Salon, the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. His time at the École cemented his place within the academic establishment, even as his Spanish-inflected realism set him somewhat apart.

Forging a Distinctive Realism

Léon Bonnat's mature style represented a unique synthesis. He skillfully blended the rigorous draftsmanship and compositional principles of the French academic tradition learned under Cogniet with the powerful naturalism, dramatic lighting, and textural richness absorbed from Velázquez and Ribera in Spain. His approach was fundamentally realist, grounded in careful observation and accurate representation, yet it differed from the Realism of contemporaries like Gustave Courbet.

While Courbet championed scenes of rural life and labor, often with a rugged, unidealized approach and a visible, textured paint application, Bonnat's realism was more polished and focused, particularly in portraiture and religious scenes. He employed a meticulous technique, rendering flesh, fabric, and objects with convincing solidity and detail. His use of light was often dramatic, employing strong chiaroscuro learned from Ribera to model form and create emotional intensity, especially in his religious works. This careful balance between observed reality and academic structure became the hallmark of his influential style.

The Celebrated Portraitist

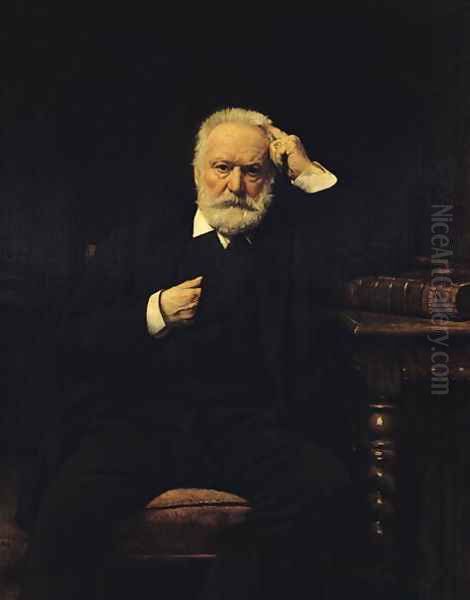

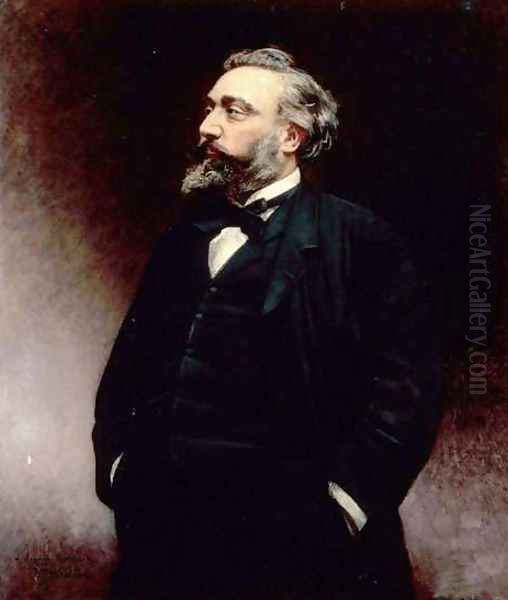

While Bonnat produced significant religious and historical paintings, his most enduring fame rests on his extraordinary career as a portrait painter. In an era before widespread photography, painted portraits were crucial for recording the likenesses of prominent individuals, and Bonnat became one of the most sought-after portraitists of the French Third Republic and beyond. His clientele included presidents, politicians, writers, scientists, artists, and members of high society.

Bonnat possessed a remarkable ability to capture not just a physical likeness but also the perceived character and social standing of his sitters. His portraits are characterized by their sober dignity, psychological acuity, and meticulous attention to detail – from the texture of fabrics to the specific features of the face and hands. He often employed dark, neutral backgrounds, drawing focus entirely onto the subject, illuminated by a carefully controlled light source, a technique reminiscent of Velázquez.

Among his most famous sitters were prominent figures such as the statesman Adolphe Thiers, the revered author Victor Hugo, the pioneering scientist Louis Pasteur, fellow painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and French Presidents like Félix Faure and Armand Fallières. These portraits served not only as personal records but also as official images that helped shape the public perception of these influential individuals. His success in this genre brought him considerable wealth and prestige.

Approach to Portraiture and Sitters

Bonnat's method for creating portraits was known to be rigorous. He demanded numerous sittings from his subjects, meticulously observing them to capture subtle nuances of expression and posture. This insistence on prolonged observation allowed him to achieve a high degree of naturalism and psychological depth. However, this demanding process sometimes led to anecdotes about his exacting nature, with some sitters finding the lengthy sessions taxing.

His pursuit of realism extended to the logical coherence of the portrayal. He aimed for an unvarnished truth, avoiding excessive flattery while still conveying the dignity appropriate to the subject's station. This commitment to verisimilitude, combined with his technical mastery in rendering form and texture, resulted in portraits that felt solid, present, and intensely real. The influence of photography, becoming increasingly prevalent, can perhaps be detected in the sharp focus and detailed rendering, yet Bonnat's works always retained the interpretive depth and painterly quality that set them apart from mechanical reproduction.

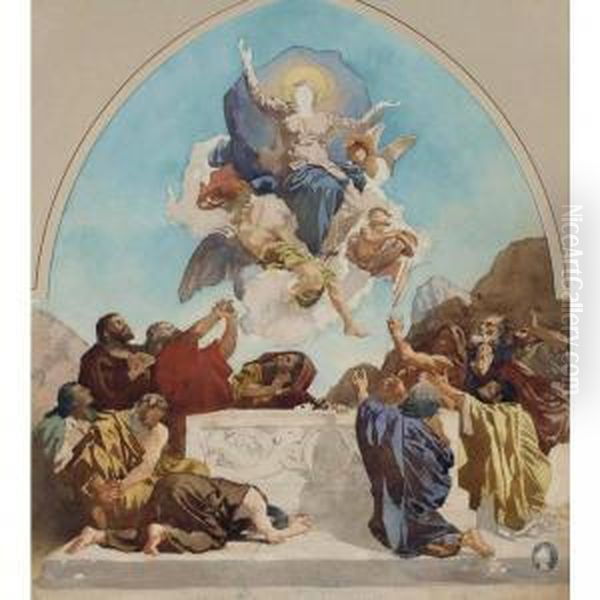

Religious and Historical Themes

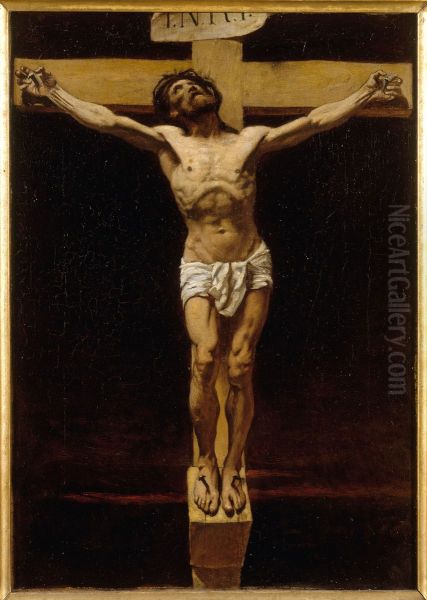

Alongside his prolific portraiture, Bonnat engaged seriously with religious and historical subjects, genres highly valued within the academic tradition. His Spanish training heavily influenced these works, often marked by dramatic intensity, strong chiaroscuro, and a stark, sometimes visceral realism that could be unsettling to contemporary viewers.

His Job (1880), depicting the suffering biblical figure, is a powerful example of his Tenebrist style, showcasing masterful anatomical rendering and conveying profound despair through pose and dramatic lighting. The Martyrdom of Saint Denis (painted for the Panthéon in Paris) and his Christ on the Cross were notable for their unflinching depiction of physical suffering. While demonstrating his technical prowess and understanding of Baroque drama, these works drew criticism from some quarters for their perceived "bloodiness" and lack of idealized spirituality, contrasting with more sanitized contemporary religious art. Bonnat, a devout Catholic, likely saw these works as having a didactic purpose, using realism to emphasize the physical reality of faith and martyrdom, following a tradition seen in Spanish religious art.

The Educator: Shaping a Generation at the École des Beaux-Arts

Bonnat's influence extended far beyond his own canvases. He became a central figure in French art education, joining the faculty of the École des Beaux-Arts as a professor in 1888. His studio became highly sought after, attracting students from France and across the globe. His reputation as a master technician and a successful artist made him a powerful draw.

His teaching philosophy emphasized the fundamental importance of drawing as the basis of all art. He stressed meticulous observation, anatomical accuracy, and the careful rendering of form. While rooted in academic principles, his instruction also incorporated the lessons he had learned from the Spanish masters, encouraging students to study light and shadow and to achieve a convincing sense of realism. He famously advocated for finding a balance between attention to detail and the overall effect of the work, ensuring that precision did not lead to a loss of unity or impact.

In 1905, Bonnat reached the pinnacle of the academic art establishment when he succeeded the sculptor Paul Dubois as the Director of the École des Beaux-Arts. In this position, he wielded considerable influence over the curriculum and direction of the institution, reinforcing its traditional values while potentially incorporating aspects of his own realist-inflected teaching. He remained director until his death in 1922.

A Roster of Notable Students

The list of artists who passed through Bonnat's studio attests to his significance as a teacher. His students included individuals who would go on to achieve international fame, often developing styles quite different from their master's, yet acknowledging the foundational skills they acquired under his tutelage.

Prominent American painters like Thomas Eakins and John Singer Sargent studied with Bonnat. Eakins absorbed the emphasis on anatomical accuracy and unvarnished realism, which became central to his own work. Sargent, while developing a much more fluid and dazzling brushwork, likely benefited from Bonnat's rigorous training in drawing and composition early in his career.

French artists who studied with Bonnat include the Post-Impressionist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, known for his dynamic depictions of Parisian nightlife. Gustave Caillebotte, associated with the Impressionists but possessing a strong realist grounding, also spent time in Bonnat's studio. Raoul Dufy and Georges Braque, who would later become key figures in Fauvism and Cubism respectively, received early academic training from him. Even the Norwegian Expressionist Edvard Munch briefly studied under Bonnat. Other students included Alfred Roll, Louis Anquetin, and the Canadian William Brymner, demonstrating the international reach of his studio. While many of these artists ultimately rejected academic constraints, the discipline learned under Bonnat often provided a solid technical foundation upon which they built their innovative styles.

Bonnat in the Parisian Art World: Salon, Contemporaries, and Controversies

Bonnat navigated the complex art world of late 19th and early 20th century Paris with considerable success. He was a stalwart of the official Paris Salon, regularly exhibiting his work and receiving numerous accolades, including the prestigious Medal of Honor in 1869 and eventually the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, France's highest order of merit. His success at the Salon cemented his reputation and secured him important commissions.

His relationship with the burgeoning avant-garde movements, particularly Impressionism, was generally one of opposition. As a leading figure at the École des Beaux-Arts and a champion of academic standards and realism derived from the Old Masters, his aesthetic stood in contrast to the Impressionists' focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and their looser brushwork. Artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro defined themselves partly in opposition to the Salon system that Bonnat represented.

However, the art world was not entirely polarized. Bonnat maintained relationships with artists outside the strictest academic circle. He reportedly had connections with Edgar Degas, who, despite exhibiting with the Impressionists, shared Bonnat's emphasis on strong drawing and classical influences. Bonnat was also known to support certain artists whose work might be considered unconventional within the Academy, such as the imaginative illustrator and painter Gustave Doré, whose inclusion in certain contexts Bonnat reportedly championed, sometimes causing friction with more conservative academicians. His position was thus complex: a pillar of the establishment, yet respected for his technical skill even by those who pursued different artistic paths, and occasionally supportive of talent that didn't fit the standard mold.

The Passionate Collector: A Legacy in Art

Beyond his own painting and teaching, Léon Bonnat was an avid and discerning art collector. Over his lifetime, he amassed a remarkable collection of paintings, drawings, and sculptures, reflecting his deep admiration for the masters who had inspired him, as well as his interest in certain contemporaries. His collection was particularly strong in Old Master drawings.

His holdings included works by artists he revered, such as Rembrandt, Rubens, Van Dyck, and his beloved Spanish masters Velázquez and Goya. He also collected works by French masters like Nicolas Poussin, Claude Lorrain, Antoine Watteau, and significantly, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose emphasis on line Bonnat deeply respected. Nineteenth-century artists like Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault were also represented. This activity reveals Bonnat's profound engagement with art history and his desire to live surrounded by the works he considered pinnacles of artistic achievement.

The Musée Bonnat-Helleu: An Enduring Gift

Léon Bonnat's dedication to art extended beyond his lifetime through an act of extraordinary generosity. Having no direct heirs, he decided to bequeath his extensive personal art collection, along with many of his own works, to his hometown of Bayonne. This bequest formed the foundation of the Musée Bonnat.

Opened shortly after his death, the museum became a significant cultural institution in the region, housing not only Bonnat's own paintings but also the impressive array of Old Master and 19th-century works he had collected. The collection was later enriched by the donation of the collection of Paul Helleu and his wife Alice, leading to its current name, the Musée Bonnat-Helleu. It stands today as a major testament to Bonnat's legacy, offering insights into his artistic tastes, his own work, and providing access to significant works of European art history far from the major metropolitan centers.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

Léon Bonnat died in Monchy-Saint-Éloi in 1922, recognized as one of France's most successful and honored artists of his time. His legacy is multifaceted. As a portraitist, he created an invaluable record of the leading figures of his era, executed with technical brilliance and psychological insight. As an educator, he transmitted rigorous academic principles and his own Spanish-inflected realism to a diverse group of students who would significantly shape the course of modern art, even as they reacted against aspects of his teaching.

In the decades following his death, as Modernism gained ascendancy, Bonnat's reputation, like that of many academic painters, suffered a decline. He was often criticized as conservative, overly academic, and resistant to the innovations of Impressionism and subsequent movements. His meticulous realism could appear photographic or lacking in expressive freedom to eyes accustomed to modernist aesthetics.

However, more recent art historical scholarship has led to a more nuanced appreciation of Bonnat and other academic artists of the period. His technical mastery is undeniable, and his role as a bridge between Spanish Baroque naturalism and late 19th-century French realism is better understood. His portraits are increasingly valued for their historical importance and artistic quality. His influence as a teacher, providing a solid technical grounding even for future avant-gardists, is acknowledged. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of Monet or Cézanne, Léon Bonnat remains a pivotal figure, a master craftsman, an influential educator, and a defining representative of a powerful current within the complex art world of nineteenth-century France. His work, and the museum founded upon his collection, continue to offer rich insights into the art and culture of his time.